Who are You: Australian Portraiture

Rex Butler

Portraiture is in at the moment. Undoubtedly, the most decisive curatorial gesture of the past several years has been the opening wall of women’s portraits and self-portraits that greeted visitors to the recent National Gallery of Australia Know My Name show. Entitled ‘Lineage’, it was a rotating three-part hang over the course of the exhibition, each time showing some sixty works in total, with for example Julie Dowling’s Mary (2001) next to Stella Bowen’s Mary Widney (1927), Ola Cohn’s Peace (1940) next to Fiona Foley’s Badtjala Woman (1994), and Vida Lahey’s Monday Morning (1912) above a shelf of shell necklaces by Dulcie and Lola Greeno (1995–8).

You looked up at its gigantic Salon-style hang and, more than any individual work of art, you saw the whole, the quantitative gesture, the statement that here were sixty women artists, with the implication—because there did not seem to be any criteria as to their selection—that any number of others could be included. The hang was a magnificent work of art in itself, which reminded one as much as anything else of a computer screen that you could scroll down once you’d fed in the search term “Australian woman artist”.

It was a brilliant expression of the paradigm shift in contemporary art from art history to the social. We are not so much interested any more in the work of art itself—its form, its materials, its relation to the history of art—as in who made it and what it is of. Portraiture might be in at the moment, but in effect every work of art is now a portrait or even better a self-portrait: the questions we ask of it concern the identity of its maker and what is their relationship to their subject matter, whether they have the right to depict what they depict and what this is to say about them.

In effect, the portrait today is not just a genre or the revival of a genre of art, but a new methodology, a new series of questions to put to the work of art itself. Or perhaps the classic art-historical questions that always get put to portraits—what is the artist’s relationship to their subject matter and how did they get to paint whom they painted—is now posed of all art. But, beyond this, we would further suggest that all art is now a self-portrait: we make no distinction between the work of art and its maker, what we most want the work of art to tell us about is its maker, or as that wall of Know My Name tells us it is the maker who becomes the work of art. Indeed, a little against what we just said above, we do not so much read its maker through the work of art but the work of art through its maker.

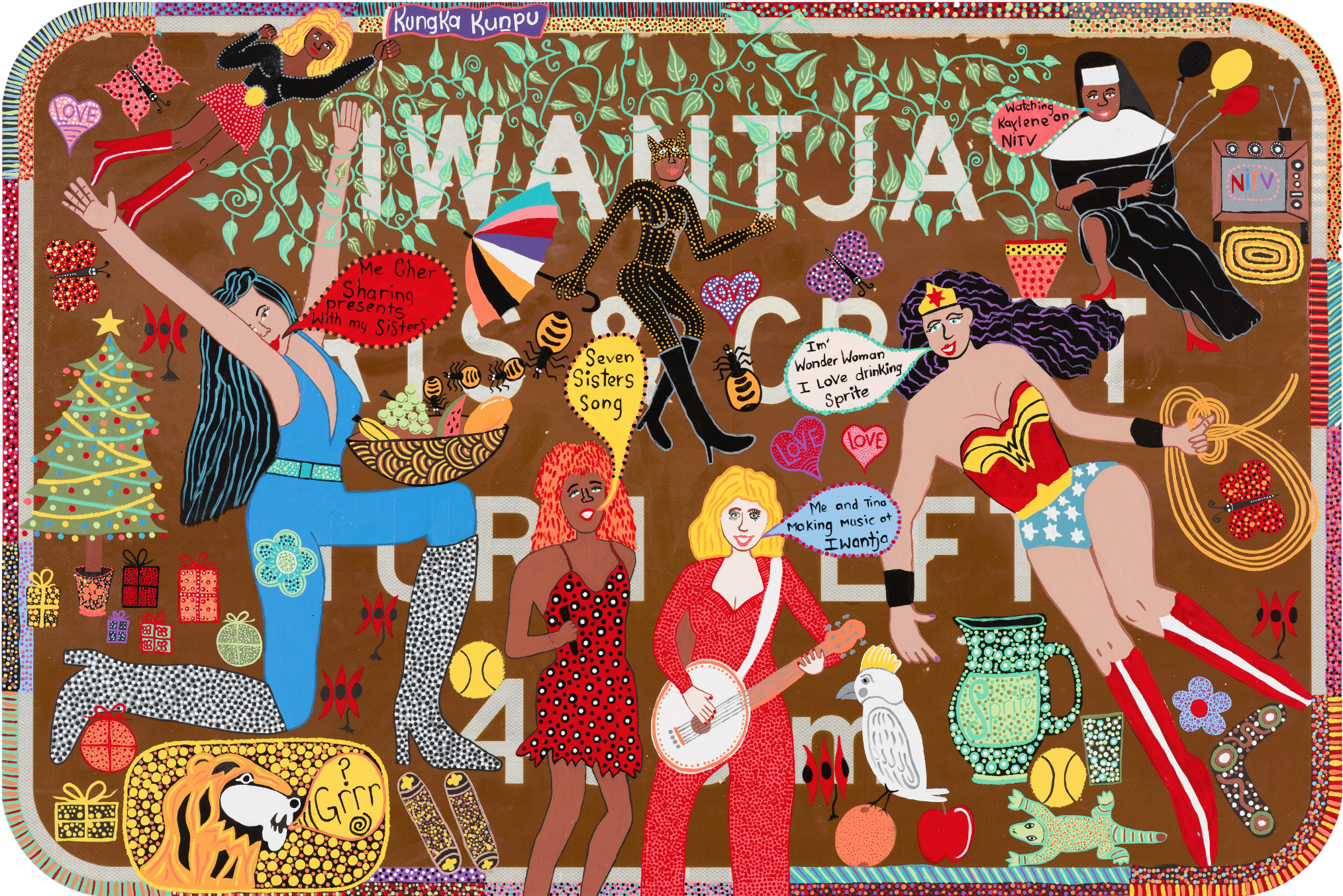

Who Are You was a huge and brilliant show that filled the entire third floor of the National Gallery of Victoria Fed Square. Drawn from the collections of the NGV and the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, it included some two hundred works of art, ranging all the way from (at least this was the earliest I could spot) Australia’s first female sculptor Theresa Walker’s 1841 cast wax medallions of explorer and early documenter of Indigenous Australians Sir George Grey and his wife through to any number of works from our post-COVID present: Brenda Crofts’ photograph of Ngambri activist Matilda House (2020); Maree Clarke’s Walert-Gum Barerarenungar (2020–21), in which some 63 possum skins and sewn inserts tell her ancestral story; and Kaylene Whiskey’s Seven Sisters Song (2021), which depicts a series of Black cartoon superheroines in enamel paint on a road sign.

The third floor of NGV Fed Square is often the “critical” floor, the one that offers a higher, more exalted take on what happens down below. This was certainly the case for the 2018 Colony show, where the curators, unable to bring the two histories together, ended up putting the contemporary Indigenous art reflecting upon white invasion two floors above the work embodying European colonisation leading up to the founding of the Gallery in 1861. (Indeed, we might even suggest that the same “critical distance” is currently to be seen at the NGV on St Kilda Road, where the Queer show hovers above Picasso and His Century like an ominous grey cloud. Oh, why didn’t the Gallery seize the moment and put on a Picasso and Women show?)

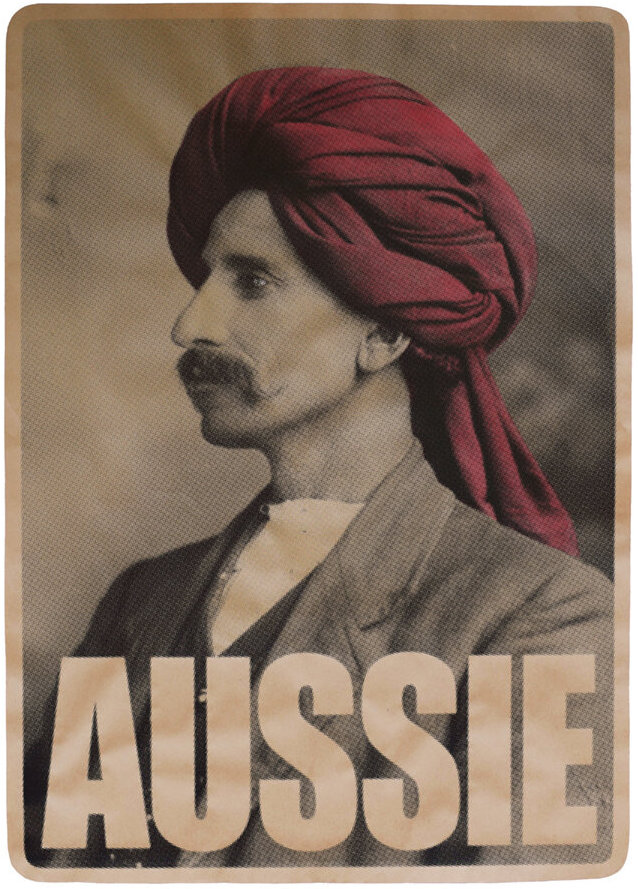

There are all kinds of thematic, social and even formal relationships to be seen between the various works in Who Are You. In the first room, devoted to people and place, we have Marshall Claxton’s image of a forlorn-looking woman, An Emigrant’s Thoughts of Home (1859), next to Peter Drew’s detourned photo of early colonial trader Monga Khan from his famous Aussie poster series (2016). In a room devoted to photography, we have Alan Constable’s glazed earthenware Cameras (2013) in a vitrine opposite Tracey Moffatt’s magisterial self-portrait of herself holding a camera (1999). In another room, devoted to celebrity, we have Fiona McMonagle’s watercolour of cricketer Elyse Perry (2016) next to a ceramic by Hermannsburg potter Rona Panangka Rubuntja celebrating AFL Player Nicky Winmar.

We even sometimes have an antagonistic relationship between works or moments when we might understand one work to be offering something of a corrective or at least another perspective onto another near or next to it. Charles Summers’ marble busts of the first town clerk of Melbourne Edmund Fitzgibbon and his wife Sarah (1877) seem to cast their eyes over a room full of portraits of Eddie Mabo, Gary Foley and Gurrumul Yunupingu, or conversely Michael Riley’s photograph of his cousin’s sister Maria seems just as regal as Polly Borland’s portrait of Queen Elizabeth II. We also occasionally have small moments of art-historical or stylistic coherence, such as when the Surrealists James Gleeson, Dusan Marek and Erik Thake are hung next to each other or when the tonalist AD Colquhuon is placed two paintings to the left of the neo-tonalist Janet Dawson.

But, in a way, these are just coincidences, momentary resemblances that are over almost as soon as they begin, like when I once saw the Queensland Art Gallery put all of the works in their collection that were blue in the same room. For ultimately, for all of the show’s gesturing towards it, Who Are You is not about how people are represented in art but rather about which people and by whom. There is a small wall of modernist images of “modern” women by Lina Bryans, Evelyn Cooper and Janet Cumbrae-Stewart, which might tell us a lot about the new looks of women in the prewar and inter-war period, the empowerment of female artists and their critical relationship to previous depictions of women, but that would be the subject of a whole show, maybe one about the coming-together of modernism in society and art. There are many depictions of Indigenous Australians by the likes of Gordon Bennett, Vernon Ah Kee, Julie Dowling and Karla Dickens, but again this is not systematically explored or analysed—and there are very few depictions of Indigenous Australians by non-Indigenous Australians. It’s been done before, but that too would be the subject of an entire exhibition.

No, the real drive of the exhibition—as of all art and culture today—is a kind of inclusivity: the crucial thing is that no one and nothing can complain of being left out. So that the show—much as with the NGA’s recently announced policy of a forty-forty-twenty gender split—as much as possible becomes a reflection of (at least its own image of) contemporary Australian society. It’s like campaigning for an election that the gallery—which, like the perfect “teal” candidate, stands for both everything and nothing—could never lose. Indeed, altogether it’s quite telling that the title of the show, which logically should include a question mark, does not. It’s not asking us who we are; it’s telling us.

Not only politics but culture is going through a profound period of populism at the moment. It’s not merely the blockbusters like the Picasso show, but exhibitions like Who Are You: it’s an art that does not in any way challenge or take a distance onto society but precisely wishes to reflect it and become an inseparable part of it. And the work of art disappears or becomes transparent at this point. It is no longer a material object that has to be understood in its own terms, but is simply the equivalent of what it is of and who it is by. Art will be an irreplaceable record of who we were—just one level below Queer, there is a series of beautiful portraits from seventeenth-century England by the likes of William Larkin, Daniel Mytens and Mary Beale that no one now ever goes to look at—but soon it will be replaced by the digital database, which can be much more inclusive, much more interactive, much more up-to-date, and in which—if we are to believe Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and TikTok—we can much more easily find out who we are and who we identify with.

There is a striking corner in the Queer show where the curators put together Margaret Preston’s Fish Bowl (1910), Bessie Gibson’s Luxembourg Gardens (c. 1910), Bessie Davison’s Girl in the Mirror (1914), Anne Alison Green’s Cherbourg Harbour (1930) and Janet Cumbrae Stewart’s Mary Cockburn Mercer (1939) (and just out of the corner of your eye you can see Ambrose Patterson’s and Alastair Cary-Elwes’ mutual portraits of each other). Here in a nutshell is the whole story of the Australian lesbian women expatriates in Paris before and after the War, who knew of each other, looked after each other, and indeed whose expatriate possibility was known back in Australia in the nationalistic ’20s. (The same might be said of the Australian gay men in London, so why not hang De Maistre near Francis Bacon?) There was so much to be said here about Australian art history, the way these women were conscious both of their sexuality and the alternative they offered to Australian art history as it was, but also of how—as seen in the way they would help generations of young Australian women arriving in Paris—they nevertheless still identified as Australian and did not give up on the idea of another possible Australia.

But it was a particular “scene” or conjunction of individuals that was soon lost in the maelstrom of “queer” in the show, which—like portraiture—seems to involve everyone and everything (Italian poets, Roman emperors, Egyptian goddesses) and functions as a kind of totalising hypothesis that cannot be refuted, insofar as everyone is in a way “queer” and even those who deny it are only hiding it from themselves (surely the implication of including the historical enemies of queer in the show).

Equally, in Who Are You, in an insightful and quite moving selection, the curators include John Nixon’s Self Portrait (Non-Objective Composition) (Yellow Cross) (1990) at the entrance to the fourth room of the show. It’s a cross that now serves, of course, as something of a memorial to Nixon, who died in 2020. In fact, we would suggest, after an initial avant-garde moment inspired by Communism and the Russian Suprematists, sometime in the early ’90s Nixon pursued an equally radical “immanence”: his work is not any more about changing the world but preserving it. The one-day shows, the artist-run spaces, the collaborations, the incessant productivity: Nixon’s practice operates as much as anything as a kind of diary that sought to record or better embody the circumstances in which it was originally made and exhibited. It was just the little art world that gathered around it: Melbourne in the ’90s, 2000s, and 2010s. The different dispositions of similar-looking objects were the attempt to hold together a fragile and precarious moment in time, of which Nixon was the centre. And it is exactly in this sense that Nixon’s works are self-portraits or autobiographical, the very image of his life. He just is his work.

But again—and this is perhaps the real memorial that Nixon’s work now represents—the function of art as a record of its time, its place, its people, as any kind of image of who we are, is coming to an end. The true equivalent to Nixon’s work today—think here of someone like Peter Tyndall—is keeping a blog, posting on Instagram or tweeting with its potentially limitless subscribers.

When every work of art becomes a self-portrait, then the art itself disappears and it is only what it is of. In the corridor near the toilets at the NGV International (obviously another place for the subconscious of art), there’s a children’s art activity centre accompanying the Picasso show, entitled Making Art: Imagine Everything is Real. But we’re all kids now and do actually imagine everything is real: that Picasso’s works just are Picasso, that portraits and self-portraits are just who they are of, that the work of art is just who made it. What’s gone missing is the art, and the next thing to vanish—despite the fact that new ones are being built everywhere—will be the art gallery.