Exterior rendering of OFFICE’s proposed refurbishment of 120 Racecourse Road, Flemington. Image courtesy of OFFICE.

Proposed Refurbishment of 120 Racecourse Road, Flemington

Moyshie Elias

The needle drops … crackle, pop, crackle … BANG goes the timpani. Cymbals crash. The brass and strings roll in with suspense. Then a hush … enter Her Majesty, Shirley Bassey. She sings: “GOLDFINGER!”

Goldfinger, the James Bond villain and eponymous film, was named after one of Bond creator Ian Fleming’s buddies: the architect Ernő Goldfinger. A staunch Marxist and modernist visionary, Goldfinger designed Trellick Tower (1967) in West London, one of the United Kingdom’s most iconic examples of brutalist public housing.

Ernő Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower (1967) in West London. Photograph by Ethan Nunn.

Trellick Tower was once maligned—accused of being crime-ridden, grime-laden, dilapidated, and unfit for purpose. It was also, to Goldfinger’s chagrin, partially privatised. As a result of Margaret Thatcher’s controversial Right to Buy policy of the 1980s, several apartments in the building were sold to tenants, who then resold them on the private market. In a bittersweet turn for Ernő, before too long—and with this injection of capital—Trellick’s apartments became highly desirable. Some of its apartments now sell for over AUD 1.8 million, rivalling the Barbican Estate’s prices. It has also been granted heritage listing.

Trellick Tower has become a symbol of architectural resilience. It demonstrates that, even after years of neglect and loathing, modernist public housing towers can be transformed from objects of disdain into desirable and cherished examples of the kind of architecture they once aspired to be.

That possibility exists here in Melbourne, too. Settle down, Dad, I’m not talking about privatisation. I’m talking about the taxpayer-funded rejuvenation of our modernist, publicly owned housing towers. With a lick of paint, any bit of mid-century junk fetches top dollar on Facebook Marketplace. We have forty-four towers worth!

Coloured Glass Windows in the Trellick Tower’s Lobby. Photograph by Steve Cadman.

OK, admittedly Melbourne’s towers aren’t quite up to Trellick standards. Goldfinger’s design is best known for its axe-like services tower, which stands in proud isolation from the main building, connected only by a vertical series of suspended walkways. Another striking move is Goldfinger’s use of coloured glass windows in Trellick’s lobby area, providing an unexpectedly joyous reprieve from the brutal monotony and greyness commonly associated with public housing towers of the same era. Setting aside Roy Prentice’s Park Towers (1970) in South Melbourne, with their symmetrical, claw-like, almost fascistic plan clutching at an austere central lift core, it’s difficult to identify comparable moments of drama and delight in Melbourne’s towers.

For the most part, our towers aren’t masterpieces. But they don’t need to go the way of Minoru Yamasaki’s Pruitt-Igoe (1954), a public housing estate in St Louis, Missouri, whose dramatic demolition in 1972 (only eighteen years after its completion) was described by architectural historian Charles Jencks as the precise moment modern architecture died, with Robert Hughes narrating its demolition in The Shock of the New series.

Shortly before his resignation, in a parting gift to Victorians, former premier Dan Andrews announced that all forty-four of our public housing towers would be demolished by 2051. But a growing number of dissidents, including writers, academics, activists, residents of the towers and even architects, are rejecting Dan’s kiss goodbye. Enter Collingwood-based architectural practice OFFICE. In their report, Retain, Repair, Reinvest (RRR): Flemington Estate (2024), OFFICE makes a clear and thorough argument for the retention of the S-type towers (this name comes from their S-shape in plan). These towers were designed and procured by the Victorian Housing Commission between 1962 and 1974, mostly under the direction of Roy Prentice. Others, including Lucia Amies and Rachel Dexter, have already argued that OFFICE’s proposal makes economic sense while foregrounding the social justice issues at the heart of public housing discourse. But there is more to OFFICE’s work than waste-not-want-not, do-gooder flair. I will argue that it’s also a compelling proposal, architecturally (gasp).

The existing S-type tower at 120 Racecourse Road, Flemington. Photograph by Ben Hosking, courtesy of OFFICE.

Let’s start with the basics. In their proposal, OFFICE focuses on the 120 Racecourse Road tower within the Flemington Public Housing Estate in Melbourne’s inner north. This tower is one of the twenty-storey high-rise public housing towers built during the 1960s as part of Melbourne’s high-density urban renewal strategy. It shares the same typology and construction as many other towers across Victoria: reinforced concrete pilotis with precast pebblecrete façade panels and a centralised lift core plan.

OFFICE’s proposal uses 120 Racecourse Road as a case study or prototype for retrofitting other towers in the estate and across the broader Victorian housing portfolio. The detailed design strategies, including balcony additions, a staged construction methodology, and public realm upgrades, are all modelled on the existing conditions at the Flemington site.

Exterior rendering of OFFICE’s proposed refurbishment, including its brick base and new balconies. Image courtesy of OFFICE.

Central to OFFICE’s proposal is the addition of balconies, which would provide much-needed architectural relief to the apartments that currently lack direct access to private outdoor space. The design drawings and diagrams for OFFICE’s 120 Racecourse Road revamp show the depth of these balconies ranging between 2.4 and 2.6 metres, spanning the full width of the living room façade, typically around six to eight metres, depending on the unit configuration. This results in a new balcony area of roughly fourteen to twenty square metres per apartment. The proposed balconies are deep enough for outdoor dining, home gym equipment, bike storage, clothes drying, and planting. They are screened with operable glazing, allowing them to be used either as an enclosed winter garden or an open balcony. They are also connected directly to internal living areas, improving light and ventilation.

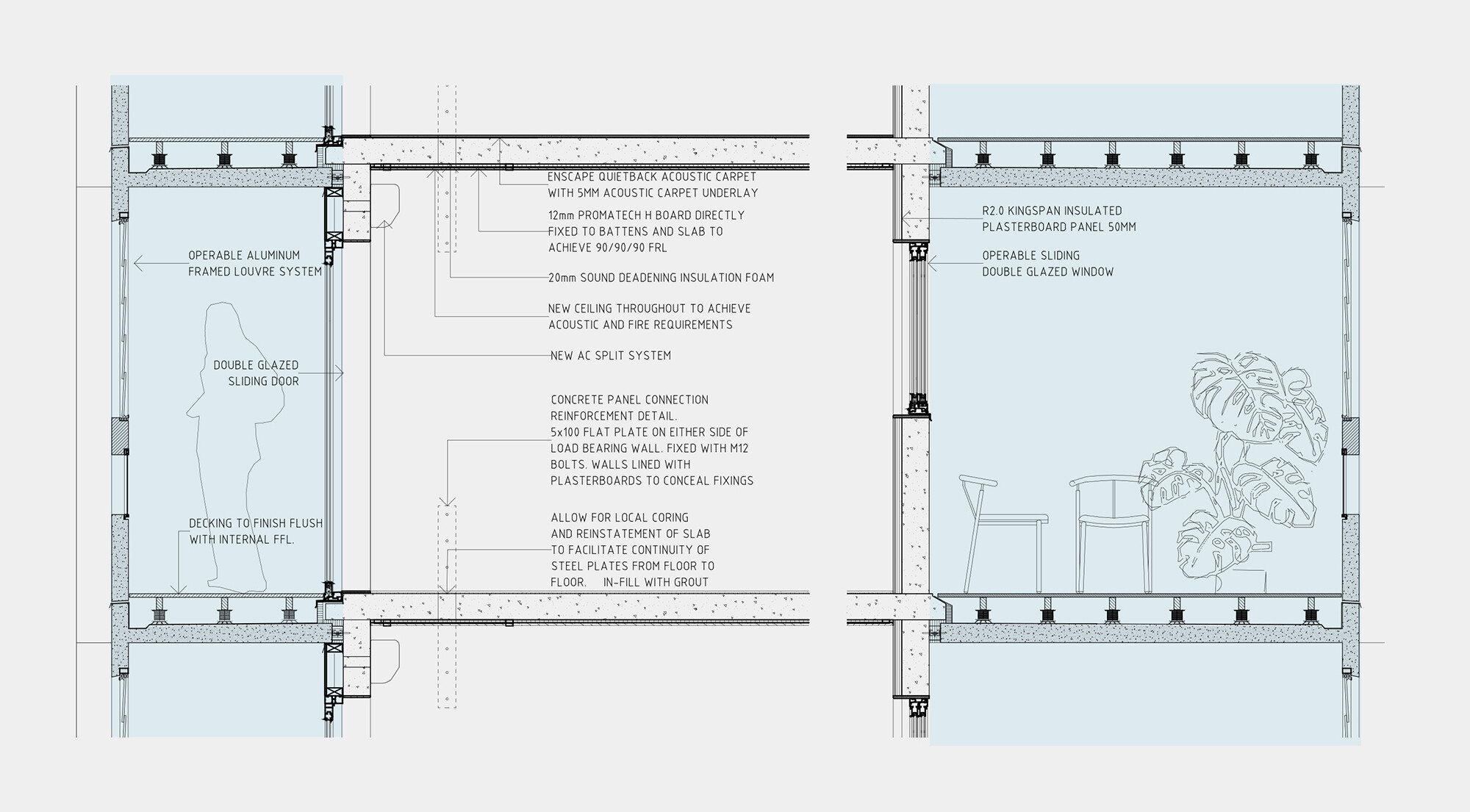

Sectional detail drawing of the new balconies and building fabric upgrades. Drawing courtesy of OFFICE, adapted by the author to highlight the new additions in blue.

Here, OFFICE follows the lead of 2021 Pritzker Prize winners Lacaton & Vassal, whose Transformation of 530 Dwellings at the Cité du Grand Parc in Bordeaux (2016) saw the addition of 3.8-metre-deep extensions to every apartment. These balconies—part winter garden, part open terrace—effectively doubled the usable façade of each dwelling.

Aside from providing new functional space, the addition of balconies in OFFICE’s proposal would also allow residents to experience their home’s façade in new ways. Over the phone, Simon Robinson (OFFICE’s co-director and architect) spoke appreciatively of the locally sourced crushed rock aggregate used in each tower’s precast panels. The distinctive brown- and beige-toned pebblecrete has, until now, been associated with the towers’ imposing façades and is visually experienced from outside and at a distance. With the addition of OFFICE’s balconies, residents could experience this exposed aggregate up close for the first time, gaining the ability to touch the outer skin of their living spaces. Texture aside, the façade’s sheer mass would also be reclaimed by residents. After being set back from the glazing line, the old precast walls would no longer be directly exposed to the weather. They would become thermal batteries: cooling apartments in the summer and warming apartments in the winter.

Close-up of the pebblecrete precast. Photograph by the author.

OFFICE’s decision to add balconies has obvious appeal, but perhaps the real architectural merit in their proposal lies in what’s saved, rather than what’s added. Critics and residents have long agreed that the existing S-type towers provide residents with a generous amount of natural light and remarkable views in both private and common areas. This is achieved via height (that old thing) and their S-shaped plan, which is almost rotationally symmetrical. Whether or not OFFICE’s attempt to recognise and preserve these qualities is in itself an architectural achievement is up for debate. What’s clear, however, is that when it comes to these fundamental architectural concerns (light and aspect), many of the buildings intended to replace the S-type towers are falling well short of their predecessors.

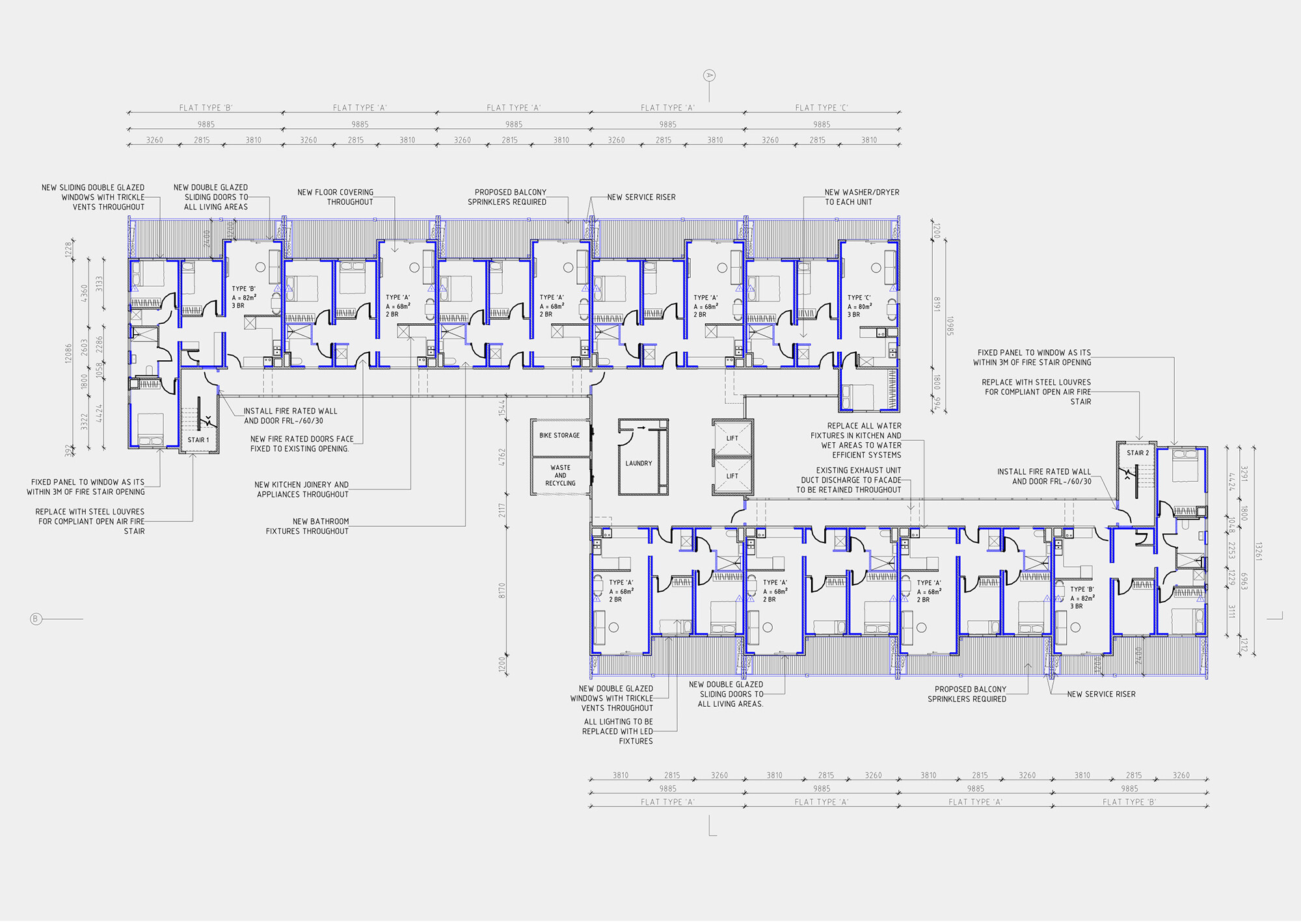

Plan drawing showing OFFICE’s proposed additions and alterations (in blue) to 120 Racecourse Road. Drawing courtesy of OFFICE.

Such projects include McBride Charles Ryan’s Abbotsford Street Social Housing (completed in 2025 as part of the North Melbourne Public Housing Renewal Program) and Six Degrees Architects’ Victoria Street Housing in Flemington (completed in 2024 and intended to replace the S-type towers, including 120 Racecourse Road). Both projects do well to produce some moments of joy in response to what must have been a doozy of a brief and a dizzyingly rapid Big Build™ procurement process. Their articulated precast façades and their communal courtyard spaces are well considered. And while I’m no urban design buff, in terms of scale, massing and density, they appear to tick some of urban design guru Jan Gehl’s boxes. But in both projects, the communal corridors on apartment levels sorely lack the natural light and panoramic views of their predecessors’ equivalents and feel more like the corridors of an Ibis Budget Hotel. Maybe it’s a bit cheap and misplaced to direct this criticism toward McBride Charles Ryan and Six Degrees. These corridor spaces likely would have fallen victim to the two monsters architects fear most: the rapacious beast that is “Value Management” (the inevitable shrinking of a project’s budget, which usually occurs at several stages throughout procurement) and the vicious devourer of good floor plans, known as “MAX NLA” (the pressure to achieve a maximum net yield of lettable area, often at the expense of good schematics).

Except for buildings on long and thin sites and the odd Nightingale Housing project, communal hallways in most new multi-residential developments are sandwiched between masses of apartments. This is an architectural tragedy. We’ve lost the promise of Alison and Peter Smithson’s streets in the sky, a brilliant vision of light-filled communal pedestrian walkways that run along a building’s façade, appearing in their work as early as their Golden Lane Estate competition entry (1952). A modest implementation of this idea is seen in the S-type towers in Flemington and many of the other public housing towers still standing in Melbourne. Realising such ideas in new social housing builds has almost become fanciful. Once again, streets in the sky are the stuff of dreams. We should cherish and upgrade the architectural examples of this ambitious vision that we have left, especially if residents enjoy them.

One such resident is Elena Suares, a law graduate from ACU whose recent pro bono work earned her an audience with the late Pope Francis. She has lived in an S-type tower at Fitzroy’s Atherton Gardens for the past eight years and generously agreed to show me around the building she proudly calls home.

As we walked through the tower, I paused to take in the gob-smacking view from the street in the sky that leads to Elena’s apartment. The apartment is filled with natural light and framed by exceptional views. Her pride and joy is the modestly sized second bedroom, which she has transformed into a study. It’s bursting with books and optimism. It’s Elena’s legal launchpad, and she hopes it will be there for her during her postgraduate studies.

A view from a street in the sky in one of Melbourne’s S-type towers. Photograph by the author.

If the government’s plans persist, Elena is at risk of losing her home. I spoke with her about OFFICE’s proposal. She was passionately supportive of their vision, which would not only allow her to remain in place but also add to her beloved apartment. Why take this architecture away from Elena, especially when doing so makes no economic sense?

I said I wouldn’t get the calculator out, but … OFFICE’s proposal is underpinned by a convincing set of metrics. The cost of demolition and full reconstruction for an S-type tower would exceed AUD 400,000 per dwelling. In contrast, OFFICE estimates that a full refurbishment (including balcony extensions, interior upgrades, lift improvements, and public realm works) could be achieved for closer to AUD 200,000 per dwelling. This represents not just fiscal prudence, but environmental responsibility: avoiding demolition means retaining the embodied carbon of the original concrete structure and minimising construction waste. The proposed staged construction methodology further allows residents to remain in place throughout, avoiding costly relocations and social displacement. The economic case aligns with the architectural one, preservation paired with performance … Ah, this review is getting a bit Price Waterhouse Coopers.

We began with Shirley Bassey and (Ernő) Goldfinger! Trellick Tower stood tall against condemnation, becoming a cherished part of London’s architectural heritage. Melbourne’s towers now face a similar inflection point. Do we erase them or reinterpret them? Do we overwrite our spatial memory or build upon it? OFFICE’s proposal offers a substantial, design-led, economically sound, and socially grounded model for refurbishment. What’s missing is the collective will to see public housing towers not as bottom-of-the-barrel accommodation for the disadvantaged, but as functional sites with heritage architectural value and irreplaceable community, worthy of investment and protection. Will the state government’s cynicism prevail? Or will the architecture of the towers win a second life? Cue that other immortal Bond theme, voiced by Nancy Sinatra: “You Only Live Twice.”

Moyshie Elias is a practising architect currently working at Pop Architecture in Naarm/Melbourne.