Katherine Botten, The Freedom Show; Ella Sutherland, Speaker of the House

Cameron Hurst

Sometimes it feels like Melbourne and Sydney exist in parallel universes. Melbourne is cool; Sydney is hot. Melbourne is emo, paranoiac, cerebral, the international home of rubbish art, committed to the bit and, at times, painfully ironic. Sydney is sensual, subtropical, embodied, colourful, committed to abstract political theorising and, at times, painfully earnest. This comparative game can swiftly descend into meaningless vagueries. However, it is undeniable that place shapes artists—or, more accurately, the important things that make up a place: the people (teachers, peers, friends, lovers, enemies), the institutions (art schools, public galleries, commercial galleries, shed galleries), the rent, the jobs, the queer scene, the parties, the migration history, the weather…

Two exhibitions on now in Melbourne represent opposite ends of current tendencies in art made in Australia. Melbourne-based Katherine Botten’s The Freedom Show at Hyacinth is a mixed media purge of exit signs, bloodied palm trees, swastikas, treble-clefs, feathery eyelashes and men’s neckties. Sydney-based Ella Sutherland’s Speaker of the House at Futures is a metered set of hard-edged abstractions that transmute the visual language of democracy into chartreuse, periwinkle and burgundy paint. Distinct as they may be on a formal level, both artists are concerned with the possibilities of painting today, with representing alternate modes of feminine subjectivity and with the power of signs and symbols. To me, both of their practices seek answers to a key question of our time: What does it mean to be free?

Hyacinth is a one-room gallery on the sixth level of the Nicholas Building. It was started in 2021 by VCA graduates Savanna Szelski, Eleanor Laver and Nicola Blumenthal. Now just the latter two run the space. Shows tend to err young, with artists currently at art school or freshly graduated, and have thus far been a mixed bag. The gallery is a protagonist in the Nicholas Building community, down the hall from printed matter tastemaker World Food Books and a floor below 99%, Chelsea Hopper’s “populist” art gallery, and longstanding artist-run initiative Blindside. Openings often bleed into one another. After a recent Friday occasion held to celebrate Botten’s show, Hyacinth were firmly reprimanded by the tenants’ group; attendees’ cigarette smoke had allegedly seeped into a nearby milliner’s studio. One can’t help but feeling slightly sorry for these chic gallerinas, battered by the nicotine winds expelled by whatever deranged group of scenesters lodge themselves in the staircase next to the space. I don’t envy them the task of enforcing the freshly instated “No Smoking” rule.

Multiple trusted sources inform me that Katherine Botten should be recognised as the original grotty girl/abject it-girl. (This VCA-ified mode of psychosexual scunge is a micro-canon in itself. Think Jenny Watson if she grew up on Tumblr and ran an esoteric Twitter account between restaging her childhood attachments in oil paint.) Botten, originally from Adelaide, has been exhibiting in Melbourne since 2013 and recently completed an MFA at Monash. Her final work was a tome of stream-of-consciousness musings on celebrity culture, relationship carnage, Melbourne art politics, personal clothing philosophies, depression, suicide, medication and New Age manifestation practices. It was unexhibitable due to interpersonal content (she installed a placeholder for the graduate show). Two excerpts have been re-published with redactions under the title Spiritual Povera (like the arte, but more metaphysical) on the critic Audrey Schmidt’s website min2.report. I wouldn’t say I read them; I experienced them. The effect is akin to being Clockwork-Oranged into the psychic browser history of an erratic, extremely online art girl, an almost unbearable experience made worthwhile by flashes of droll brilliance. The fashion observations are so good: “It’s crazy what can become of your life when you don’t have the right shoe”; “I have a basic wardrobe that is clean, acceptable, neat, agreeable, no holes. All the basics are covered for work, play, outings, casual meetups with friends, sports, socialising, and impressing others competitively on the sexual marketplace”; “David’s collar is a fear based bandaid”. To say it needs editing would be to miss the point.

The Freedom Show translates the sensibility of the Spiritual Povera text into material form. Four drawings, three paintings and three wall works are hung in Hyacinth. Symbols that recur throughout the exhibition are within the syntax of the Spiritual Povera universe. In conversation, Botten stressed the importance of “vibrational frequencies” and ambiguous association over any singular interpretation. Why palm trees? Glamour, LA boulevards, movies, but also a malevolent presence (the background is blood red), Adelaide, Footscray… Exit signs reappear in three scuffy paintings. To me, they signified nihilism, out clauses, perhaps a desire to “leave society”. When we spoke about the show, Schmidt said the exit signs reminded her of the so-called Dark Enlightenment. Botten said claustrophobia. And why the neck ties? Death by hanging, fashionable formal wear, the futility of corporate culture… At the opening, the philosopher Vincent Le had a typically psychoanalytic take. “I mean… daddy issues, right?” More on this later.

The drawings, in particular, invoke woman-on-the-edge outsider artists like Carol Rama or Aloïse Corbaz or the wilting psychedelia of the classic Japanese watercolour animation Belladonna of Sadness (1973). In KB (Music), a woman’s moon-like face fills the majority of the page. A treble-clef hangs directly over her wide, blank eyes and pink pout. It could be ominous. Alternatively, the swirling form could be talismanic—as though “music” acts as a protector, an entity that stands between overwhelming subjectivity and the external world.

Lots of people posted photos of another treble-clef in the exhibition, a work made from gaffa-taped ties stuck to the wall. Shockingly, far fewer people posted photos of the swastika works, also made from gaffa-taped-up ties. What to make of these works? While there’s never necessarily a good time to exhibit swastikas, right now seems particularly bad. Kanye West’s extended meltdown is the most obvious example of a rising tide of global antisemitism. Victoria just legally banned public displays of swastikas in response to the increasingly violent activities of white supremacist organisations (religious and artistic uses are exempt). Initially, I thought the swastika tie works were dumb trolling. Then I wondered if, being so obviously offensive yet wavily non-committal, they were a meta-commentary on dumb trolling: subversion through replication. It turns out Botten has been exhibiting swastikas for nearly a decade, which makes the inclusion in The Freedom Show seem less immediately reactionary. Instead, it seems more like another iteration of a long-term compulsion with shifting intentions. An irrepressible desire for cancellation seems practically inbuilt into this show—perhaps a protective, self-destructive mechanism of sorts?—but it would be too easy to deliver that.

Artists have long been drawn to swastikas for various reasons. Botten’s work can be contextualised in relation to many predecessors and peers. See, for some initial examples, Vivienne Westwood, Eddie Chambers, Martin Kippenberger, Jake and Dinos Chapman and Paul Yore. A recent exchange between the artists Jordan Wolfson and Anne Imhof captures current debate around the topic:

Wolfson: Just because you’re using triggering content doesn’t mean you support that triggering content. It means that you’re showing it for a reason. Because it’s art, and you’re opening up a conversation, which is what art is supposed to do. I don’t like Nazis, but if I wanted to use a swastika in one of my artworks, I certainly would. You know what I mean?

Imhof: I wouldn’t.

Wolfson: Right, you wouldn’t. But as a Jew, I would, because I would be speaking to something. I’m not approving swastikas, but I’m speaking to them.

Imhof wouldn’t. Wolfson would, but hasn’t. One recent example of artists who would and did is in the People of Colour exhibition held at Mercy Pictures artist-run gallery in Auckland in 2020. Over four hundred equally-sized flag paintings associated with different nations and organisations were displayed in an affectless, emoji-like provocation which produced substantial backlash. Closer to home is Zac Segbedzi, who has made use of the swastika in his public grappling with his Jewish heritage and familial demons—although West Space did cover the symbol up. The paternal authority neckties that make up Botten’s iterations in The Freedom Show also recall a work shown at Guzzler by another key member of this VCA cohort/ cult: Hana Earles’ hard-edge abstract tie painting, Bruce Earles.

It’s impossible to pick who has the biggest daddy issues here. Instead, it’s generative to turn once more to ancestral figures, the most fitting being the mid-century American poet Sylvia Plath. I think Plath, truly the original abject it-lit-girl, shares the highest vibrational frequency with Botten. Have you heard the poet read Daddy (1960)? It gives me chills every time.

You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,

Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.

Daddy, I have had to kill you.

You died before I had time—

Daddy is enduringly controversial because Plath, who is not Jewish, analogises her abusive relationship with her dead father to the broader experiences of Jewish people in Nazi Germany. It is an obscenely narcissistic poem. This is integral to its effectiveness. The appropriation of collective history (swastika imagery) to express individual trauma is the supreme act of feminine hysteria and artistic egomania that—Plath fans would argue—through sheer, shocking indulgence is transmogrified into the universalism of great art. Plath succeeds. Does Botten?

While you contemplate, allow me to consider Futures. Zara Sigglekow and Steven Stewart opened the space in Easey Street, Collingwood, in 2021. Sigglekow is an art writer and former Neon Parc gallerist, and Stewart is an American art world refugee who shuttered a moderately successful New York gallery in 2016. The pair are savvy purveyors of eminently sellable work, a salve in a market grimly devoid of mid-tier commercial acumen. A Matthew Harris work first shown at the gallery was recently acquired by the NGV; every single painting sold in a recent solo show by the folk-Cubist Tim Bučković. I first encountered Futures in some memorable press in the Australian Financial Review, wherein Stewart reflected on the duo’s decision not to squander valuable time sitting in their stall at the Melbourne Art Fair:

“It’s about provocation”, Stewart explains. “It’s about speaking to the absenteeism surrounding social events”.

He adds: “It’s also about laziness. I mean, we don’t want to f***ing hang out in an art fair all day”.

Amen, dude. But even with self-proclaimed laziness factored in, Futures have been busy.

Ella Sutherland’s Speaker of the House follows a packed roster of exhibitions from local and international artists. The artist was born in Auckland, has lived in Sydney for the past half-decade or so, is represented by Sumer, a gallery based in Tauranga, and flew to Berlin this week to begin a delayed Creative New Zealand Visual Arts Residency. She’s also been busy.

Sutherland is a cerebral modernist. A background in book design informs her interest in typefaces and her perfectly calibrated colour combinations, which exude a precise hum. Her practice is reminiscent of the playful pedagogy of Emily Floyd, Darcey Bella Arnold’s meticulous typesetting and the semiotically dense colour field experiments of Agatha Gothe-Snape. She has also conducted extensive research into queer and lesbian archives in Australia and New Zealand; Sutherland is like if painters Bridget Riley and Josef Albers developed a latent interest in queer theorists Heather Love and Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick.

One of my favourite Sutherland works is Glyph, a body (2020). The artist was looking into Wicked Women, a lesbian S&M erotica magazine published in Sydney in the late 1980s and early 1990s by editors, partners and certified babes Jasper Laybutt and Lisa Salmon. Laybutt and Salmon also founded G.O.D—”Girls of Dishonour”/ “Guys of Disgrace”/ “Girls on Drugs”—a militant anti-homophobic protection group who patrolled the streets in matching uniforms. (To return briefly to Plath: “Every woman adores a Fascist”.) The typewriter that Laybutt and Salmon used to create Wicked Women had a broken “W”; they were forced to manually press the letter in every issue. In Glyph, a body, Sutherland resized and reprinted the unique, fuzzy Ws, making visible the combination of mechanised production and queer labour that went into printing the zine. Fifteen Ws are printed on thick, deckle-edged paper sheets. Each sheet is pressed into buckled shape under red steel constraints. It’s very chic. Lesbian interrogations of archives are an established tradition that often comprise of filmed interviews with frumpy and enthusiastic librarians and Ken Burns zooms of decaying printed matter. This is not a critique—I adore The Watermelon Woman (1996) and send my consolations to anyone who missed Cinematheque’s Barbara Hammer season. It’s to observe that Sutherland’s coolly modern formal vernacular is a departure from a dominant style of re-presenting queer archival research. Glyph, a body is an affirmation of the continual inventiveness of artists taking queer histories as their subject.

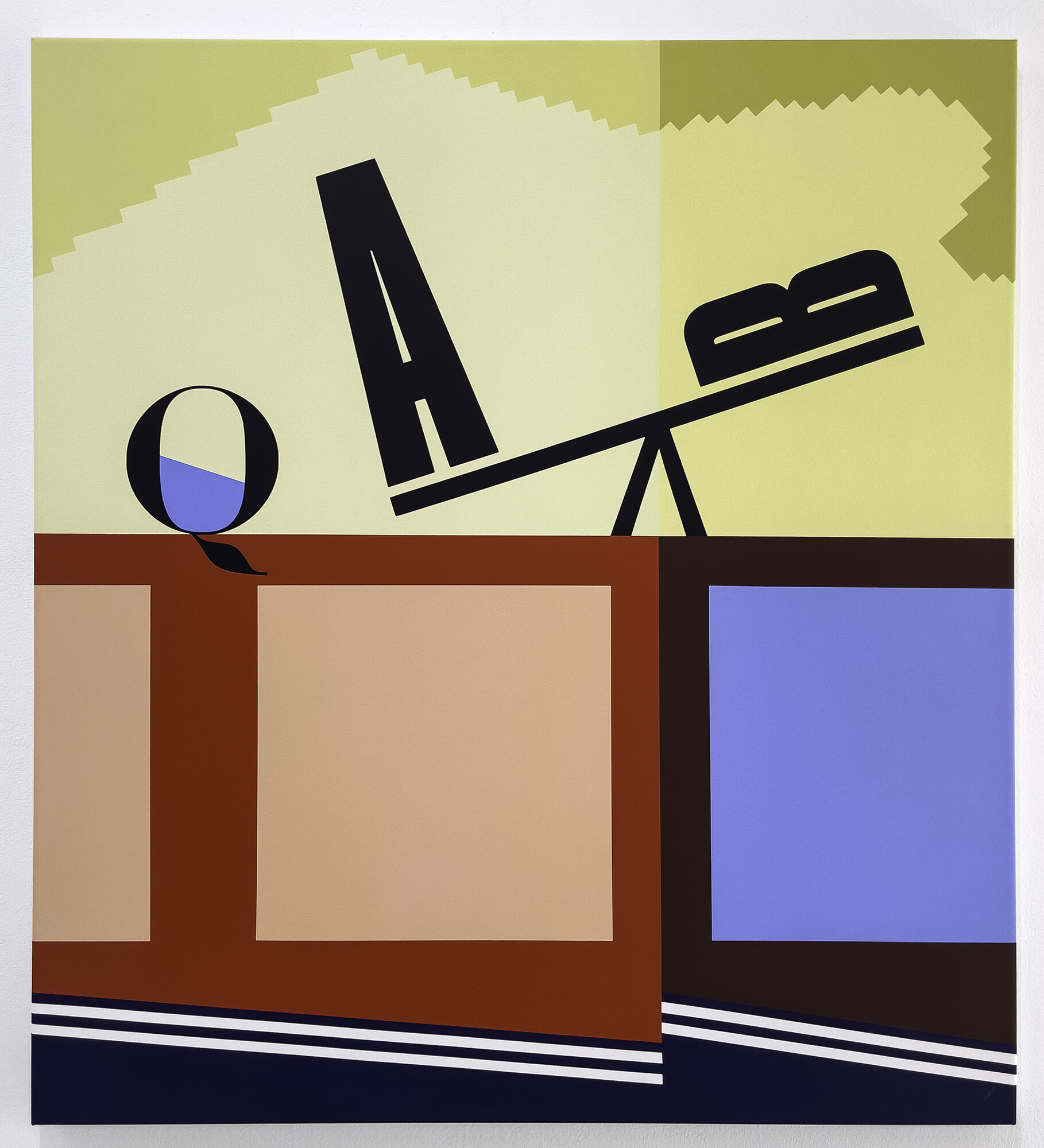

This area of research is not the primary focus of the current Futures show, though. Instead, Sutherland tells me that in the lead-up to this year’s Australian federal election, she became interested in collating the visual materials that bombard citizens throughout the process. There was something absurd about the complex democratic beast animating all those pieces of paper. “How do you make a visual representation of decision-making?” she asked. The works in Speaker of the House are the result. Ballot papers are translated into flat planes of creamy paint. The semi-circular geometry of the House of Representatives is pared back into three arches, with the “rogue character” of the asterisk bouncing between the central void. Elongated “A” and “B” letters wobble on a scale next to a “Q” with an interior circle filled by an angled blue section that looks like tilting water. The implication seems to be that our political system teeters on the edge of preposterousness.

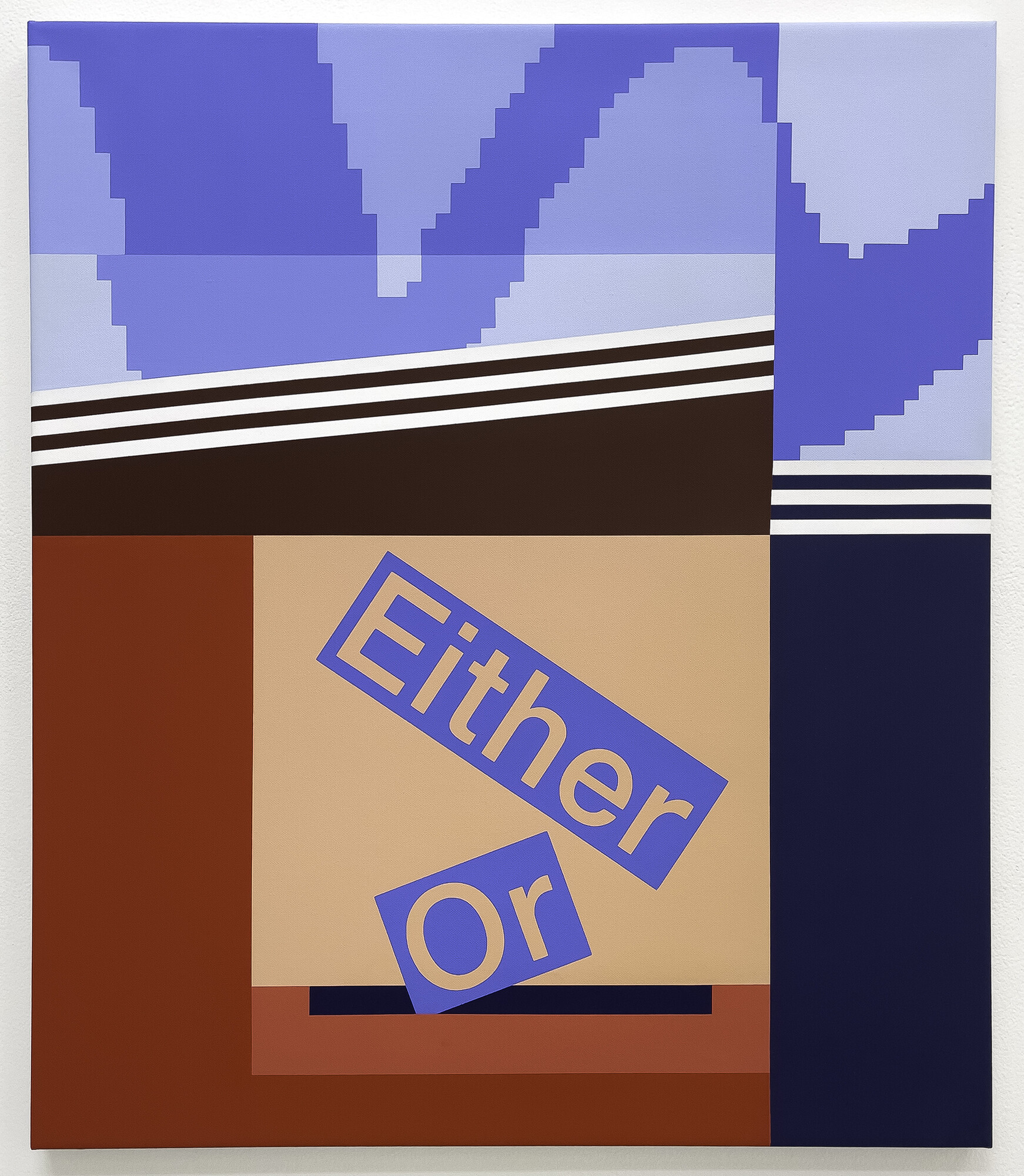

In a way, Speaker of the House is far more politically nihilistic than Botten’s Hyacinth show. One painting shows two slips labelled “Either” and “Or” in identical font and colour disappearing into a navy slot. The “A” and “B” parties seem like they would look interchangeably good in any living room filled with expensive Scandinavian furniture. Comme ci, comme ça, nothing really changes under capitalist realist, centre right neoliberalism (debatable). The works also seemingly reference Søren Kierkegaard’s book Either/ Or (1843), wherein the philosopher sets up a dialectic between two figures, A and B. The pair represent opposing life views. A is a young aesthete, driven by eroticism and frivolity, while B is an older ethicist, a married man of responsibility and commitment. In Either/ Or, Kierkegaard dramatises the existential question of how a good life should be lived.

Put another way, what is freedom? “Can you think of a more depleted, imprecise, or weaponised word?” asks Maggie Nelson. Not to mention a more American one. Still, we live in a free country—unless you are mourning Cassius Turvey or a “freedom fighter” marching against Dan Andrews’ dictatorship. Sutherland reduces the visual clauses of this dubitable democratic truism to their simplest forms, revealing their thinness. (And aren’t all stagings of queer histories a rejection of the unfreedom of the closet?) In The Freedom Show, Botten gives us an offering of tragic hopefulness. It’s one more output in a continuous project to hold the horror vacui of daily existence at bay, whether that be through communion with mystical art angels or a monk-like dedication to archiving silver eyeshadow swatch images.

“Freedom is hard to bear”, James Baldwin, one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, once said. Going on, Baldwin dissolves the illusion of rational political discourse into a divine morass: “It can be objected that I am speaking of political freedom in spiritual terms, but the political institutions of any nation are always menaced and are ultimately controlled by the spiritual state of that nation”. The spiritual and the logical are not as distant as we might think. Take a deep breath in. Breathe out. Allow trivial differences to melt away. Breathe in. Close your eyes. What colours do you see behind your lids? Can you feel the presence of freedom? It’s out there. It just depends on what form you want it in.

Cameron Hurst is a contributing editor of Memo Review.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of MERIDIAN SCULPTURE.