The Tennant Creek Brio

Lévi McLean and Paris Lettau

In 2016, a men’s art therapy group was founded at Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory. Three years later, the group has flung itself onto the international stage at the 22nd Biennale of Sydney: NIRIN as the artist collective the “Tennant Creek Brio”. Initially spearheaded by Joseph Jungarayi Williams—then working at Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation—and Rupert Betheras—an artist and ex-professional AFL player from Collingwood—the collective brings together a cross-cultural formation of five northern and central desert language groups (Warumungu, Warlmunpa, Warlpiri, Kaytetye and Alyawarr) and a painter from Melbourne. Together, they celebrate a creole of artistic traditions, some inherited, others improvised. At Tennant Creek’s cultural crossroad, the Brio’s members—Fabian Brown Japaljarri, Marcus Camphoo Kemarre, Jimmy Frank Jnr Jupurrula, Lindsay Nelson Jakamarra, Clifford Thompson Japaljarri, Williams and Betheras—command bewildering aesthetic power in a strategy of healing and resistance to cultural alienation.

Within Warumungu country, such resistance is not without precedent. Warumungu warriors led a successful counterattack upon early white invaders, forcing the first European explorer in the region, John McDouall Stuart, to abandon his 1860 expedition and retreat two-thousand kilometres back to Adelaide. In 1862, Stuart would return to complete his quest, paving the way for the Overland Telegraph Line that tentacled the country into the grip of the British Empire, linking Adelaide to Darwin and Australia to Britain. In Warumungu language, telegraphic technology would come to be called Watilikki. Aptly, the same word is used to describe nerve tendons and their network of neurotransmitters, a spider’s web, and also the path of the ancestral snake that sculpted in its wake the shape of the sky. Through the symbolic order of these communication lines, the Tennant Creek Brio renegotiate the ideological and social relations of the so-called peripheries and centres of contemporary cultural exchange.

As the site of renegotiation, Tennant Creek has an inimitable psychogeography as an ambiguous town. Both remote community and urban township, it is caught in the perceived dysfunction of neither this nor that—that Western cliché of Indigenous fate, being trapped in a pincer movement and “lost between two worlds”. The same cliché resulted in the typecasting of one of Australia’s most well-known historical artists, Albert Namatjira, whose paintings captivated fine art galleries, remote communities and even the Queen of Australia. It’s a cliché that somehow grips the nation’s psyche, even underpinning author Anna Krien’s recent article “Desert bloom: The Tennant Creek Brio”, published in the progressive Melbourne publication The Monthly. True to the lie, Krien outcasts Tennant Creek. “It is a mongrel place”, she writes, “it exists on the fringes of white and Indigenous worlds, belonging to neither.”

Perhaps this platitude explains why we can also detect an uncanny parallel between Tennant Creek and a similarly ill-conceived entrapment that the white art teacher Geoffrey Bardon described through Biblical metaphors at Papunya Tula, where in 1971 the first Aboriginal canvas boards emerged and came to typify today’s popular conception of Australian Aboriginal art. To Bardon, art seemingly leaped out from within the all-consuming abyss of being between two worlds. Instead of severing the mythic ancestral heroes from the present, as modernity seemingly demanded, the Papunya Tula artists imagined them as coiled springs which would propel them, the artists, beyond this edge.

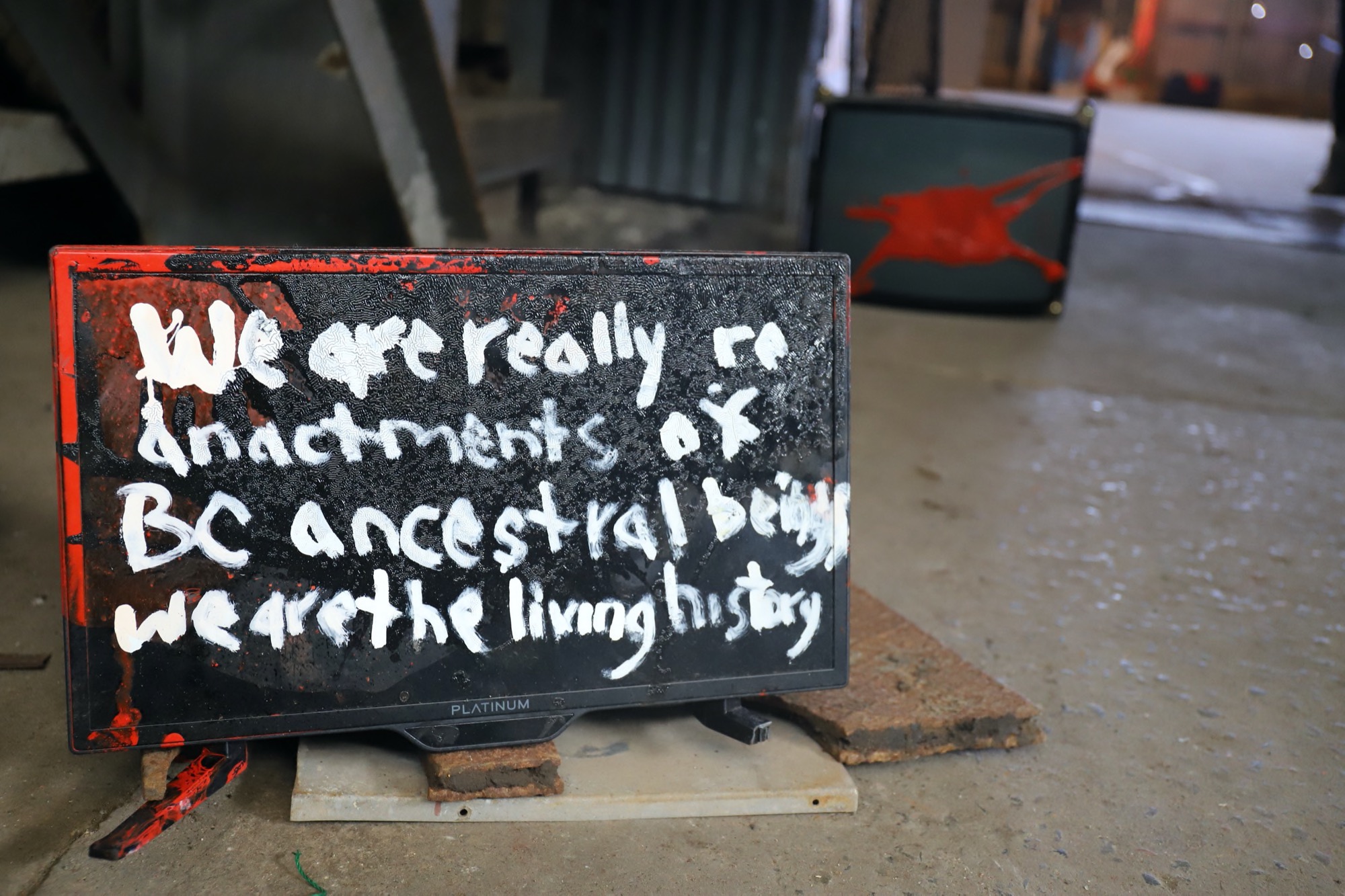

That was then and there. Today, at Tennant Creek, old ancestral heroes mix with the new, brought here by modernity as it cut its way through the place, like a cyclops sucking and consuming everything in a whirlwind. In the Brio’s work, these ancestral heroes manifest as figurations of demons, anonymous monarchs and warriors, appearing across Brown and Betheras’s collaborative Ancestor Boards series (Horus, The King, Warrior, Life Cycle) as well as the group’s miscellany of pokie machines and wounded LCD monitors. Some of them are imbued with Winkarra (the Dreaming) and prosthetic screens that sing out fragments of ceremony, audio-visually recalling country; one of them, a repurposed pokie machine, speared from all sides; all of them, repainted, reimagined and restored. The Brio collective gleefully reference this medley of ancestral heroes. Their impish reconstructions pastiche modernity’s former ferocity and subsequent wreckage, and its relentless narratives of capitalism and European settlement.

NIRIN is easily the Brio’s most significant showing to date, and it has brought the group international exposure and local renown. Their work appears across two of the Biennale’s sites: at the star venue Cockatoo Island in We are the Living History, and at Artspace in Gangsters of Art.

Perhaps the most poignant and experimental pastiche of all took place at the public opening of Artspace, where the Brio’s exhibit Gangsters of Art is staged. In an avant-garde corroboree, Joseph Williams recited his poem Masonic Warriors. A story of Manu (Country), it begins by appropriating the opening passage from a 1930s newspaper article written about Williams’ grandfather, a well-known artist, tracker, and culture-man from Tennant Creek— “Black Boy Nat”, the newspaper reads, but Williams knows him as “Tracker Nat”. All the while, in the background, Frank Jnr and Brown, with metronomic boomerang strikes, held the rhythm, invocating Warumungu song lines in language, a chorus that Williams—after reciting his poem in English—would ultimately join.

Further downstream of Parramatta River, at Cockatoo Island, mythic invocations go just as deep. We are the Living History weaves various stories—narratives that disclose truths about invasion, industrialisation, alienation, adaptation, and ancestral and cultural power: aspects of modernity captured in a contemporary epic myth of subterfuge, war, trauma, class tension, brotherhood, beauty, and healing. Like Odysseus, who enlisted the Greek master-craftsman Epeius, the Brio have enlisted their own Warumungu master-carpenters, Jimmy Frank Jnr and Joseph Williams, to fabricate a Trojan Horse: One Eyed Man. Exhibited within Cockatoo Island’s cavernous industrial space, One Eyed Man is a sculpture that has been hoisted atop a heavy steel bench and chained off. Bright yellow and speared through on all sides, it ogles down, all-seeing, all-knowing, powerful. Almost cute, it is more mutant Disney-Pixar WALL-E than Lord of the Ring’s Sauron. It is one of several works fabricated from old pokies, the one-armed bandits that once filled Tennant Creek’s notorious nightclub Shaft, each thematised with kitsch cultural appropriations: Great Wall of China, The Titan, India Dreaming, Pot of Gold. At Shaft, calculated jingles once sung out day-and-night amidst the club’s sloganeering: “WIN 10 FREE GAMES • PRIZES ARE TRIPLED”.

Frank Jnr describes One Eyed Man as a metaphor for the unholy union and limited vision of Tennant Creek’s ghosts: pastoralists, private ventures, publicans, mining prospectors and rogue missionaries. Staring at the One Eyed Man, one glimpses uncanny ghosts of an anachronistic industrial modernity that is all around in the rusted machinery and halls of Cockatoo Island, like some long-dead beached whale in which an ancestral hero stirs.

On one level, One Eyed Man is a newly arrived archive: a contemporary repository of Warumungu song trumpeting the eternal return of ancestral power, still strong even after the desecration and plunder of Country by centuries of colonisation. On another level, One Eyed Man is being punished for the transgressions perpetrated in its previous life as a pokie machine; as Frank Jnr says, for its crimes upon the country. Less apparent is that the One Eyed Man is also “getting sung”. It is a spiritual torment inflicted upon this re-imagined colonial machine by song that can be heard emanating from a TV prosthesis in its mechanical belly, as Warumungu invocations play over footage taken at the edge of Lake Surprise, a site near Tennant Creek connected to one of the last recorded mass-killings of First Nations peoples in Australia, the Coniston Massacre (also referenced by another another work, Memories of the Coniston Massacre). Like contested territorialised mapping, the boundaries in the film constantly shift in a seamless, hypnotic loop. A footprint on the shore of the abstracted lake perhaps alludes to trespass or flight, and also to “edge”. A subtle, mesmerising chromatic range, like the light show experienced when driving into the desert sun, golden and blinding, is ultimately eclipsed by the shafts of light from the open windows of the room itself—as if to remind us that this is Cockatoo Island, where the plague first took hold of the Australian continent, not its faraway centre.

Also hung around the space is a series of LCD televisions and computer monitors with gestural, tachist paint strokes, chemical-like bleeds and traditional white and ochre designs. They are limp reanimations, hung by chains suspended from large rusted industrial meat hooks. Further strewn around the space, seemingly wherever room can be found, are a series of one-metre squared Masonite boards that are in some ways indistinguishable from the miscellany of cardboard and plywood detritus scattered about this industrial tin shed. These are painted with suggestive ancestral figures that also appear in a series of larger works stacked from floor to ceiling up Cockatoo Island’s imposing lift shaft: a Black Zeus, a Pharaoh, a radiant seraph with wings spread. They’re a stairway to heaven. They’re Aboriginal, Western, ancient, prophetic, European, African, and not quite any of these. We are really re-enactments of BC ancestral beings we are the living history, scrawled in white paint across the red background of one work.

The Brio are not particular about their heroes, as it’s the ancestral power of these heroes that they want to channel. The same can be said of their art historical heroes. The Brio pay homage, in their very loose fashion, with all manner of art. There are the board backdrops that reference Papunya; the alchemic equations and fauvist spills by Betheras; Brown’s psycho-surrealist anthropomorphisms; the pulsating minimalist linework of Camphoo (aka, Double O). There’s even Wilson’s Dadaist performance, seen in footage from 15 Lions, Peekaboo donning a motorcycle helmet, while executing open-screen surgery on a discarded cathode-ray TV with a salvaged rusted naval contraption found in Port Darwin.

What the Brio’s sudden artworld discovery means, however—their catapult from obscurity to the centre of Brook Andrew’s Sydney Biennale—is too early to tell. With a feature article in the Sydney Morning Herald, and features in Art Guide, Artlink and Art Agenda (to name a few), the Brio have made the first crack into “Captain Cook culture”, as Williams calls it. But will it be a flash in the pan, their fifteen minutes of fame, or will NIRIN lead to something more enduring for them?

NIRIN, which is Wiradjuri for edge, is an appropriate metaphor for the cutting-edge ambitions of biennales. It is a word that suggests many things—especially in a biennale that focuses on First Nations art, and one directed by an Aboriginal artist, Brook Andrew, whose work, with multiple metaphors and labyrinthine allegories, examines the violent epistemological ruptures of colonialism and its aftermaths. Andrew’s work has in recent years moved beyond the traditional artistic confines of collaged paintings and photographs where he began, into museum-scale, archivally grounded installations of which NIRIN is certainly the zenith. Indeed, NIRIN can be understood as a vast installation by Andrew that draws modernity’s constellations of powerful archival objects, by Western and First Nations cultural heroes alike, into the biennale’s orbit. Andrew appropriates these objects—and in a certain sense, the Biennale’s artists themselves—to reorganise the memories and stories they have accumulated into histories of the present, as if each must surf a temporal crest of meaning. Andrew thus makes NIRIN into a self-generating machine of allegories—a speaking for the other. But the Brio are not a metaphor or allegory of the edge; they are the edge or, if you like, a real allegory. Like Andrew, they appropriate and mix images from multiple sources—ancestral, archival and mundane—to tell their stories of being this edge.

The Brio’s strategy thus shares as much with Andrew’s own artistic practice as it does with traditional Aboriginal art (indeed all art), which draws on powerful design and ancestral or archival presences. In their modern pantheons, Western myths and heroes are remixed. This process of appropriation and re-appropriation is, for them, reverse assimilation—or a resistance to their assimilation by these myths, which recognises and appropriates their power against them. Where is the edge here? If Western myths of assimilation sought to cut Indigenous futures from their past—their ancestors—then the Brio’s appropriations and re-appropriations, in shuttling indiscriminately—boldly and artlessly—back and forth across this divide, blunt its cut. These passages across differences, which necromantically re-call the dead to activate their mythical power for other purposes, carry the hope of transforming the traumatic vestiges of colonial histories into a generative form of historical reconstruction and healing.

We can understand the Brio’s strategy as similar to that described by Nigerian scholar Denis Ekpo with regard to the postcolonial African critic, whom he envisaged to be a Trojan Horse rather than a battering ram, tricking its way into the gates of power:

the West is a strange force of nature whose secrets and powers should instead be studied, decoded and made use of … the critic of imperialist reason, should not act as accuser, but as a cross-cultural spy at that tribunal, looking for openings and cracks such that, even though he lacks the means to blow up the edifice, would at least content him with knowing the secret foundations of a tribunal whose rules ensure that only winners (the West) will always win and losers will always lose.

The unassailable walls of Troy are the post-imperial world’s institutionalised cultural events, such as the Biennale of Sydney, which have long been a bastion of Western art. Andrew, a master student of European knowledge systems and expert in the powers of reverse assimilation (appropriation) as a decoding device, has effectively sneaked through its gates without lifting a sword and brought the Brio along to reap the spoils.

The Tennant Creek Brio are an unlikely accomplice. Theirs is a story of the streets, the boondocks and the Bush. At one end of the country, in ‘80s Melbourne, one member was graffitiing trains completely oblivious to the new wave of postmodernism that would soon beset art school students like Andrew. At the other end of the country, in Darwin, another etched street art into bridges; while others, yet to be born, would become, like their forebears, song-men and artefact makers. A pre-history that criss-crosses time and style in such a dizzying way would, perhaps understandably, produce a school of artworks that are equally bamboozling.

Lévi McLean is writer, and experimental film maker from Western Australia currently based in Tennant Creek. He graduated in 2019 from UWA with a BA, majoring in Art History.

Paris Lettau is a writer based in Melbourne.

Thank you to the manager of Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Cultural centre, Erica Izett, for support and feedback.