Sidney McMahon: Maggot

Nick Croggon

Maggot is a trap. The exhibition—a new installation by Sydney-based artist Sidney McMahon—lures you in with a sultry blue light. The hue evokes the familiar blue of the Windows error message, and its even diffusion across the UTS Gallery’s space transfigures its rectangle box into a virtual holding zone, a scene of suspended operations awaiting the user’s intervention.

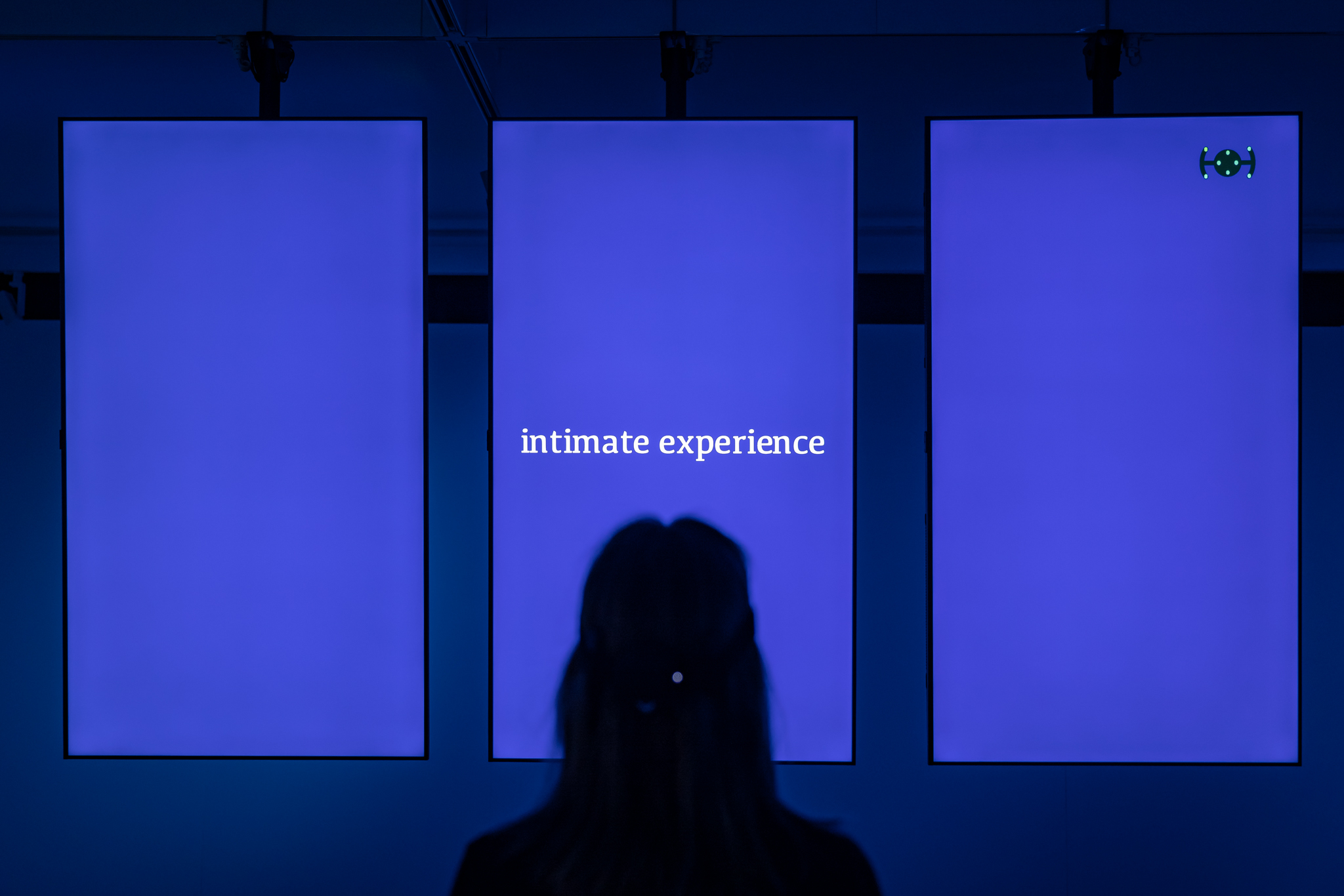

The exhibition further draws you in with a triptych of glowing screens, which hang from the ceiling in the centre of the gallery. As you position yourself in front of the screens, a crisp white text politely explains the rules for this interactive work, narrated by a deep modulated voice that emanates from the wall behind you. The narrator invites you to strap on a headset that will sync with your brain. The headset contains a sensor, the narrator explains, that should be fixed to the back of your scalp, close to your skin: “Can you feel it?”

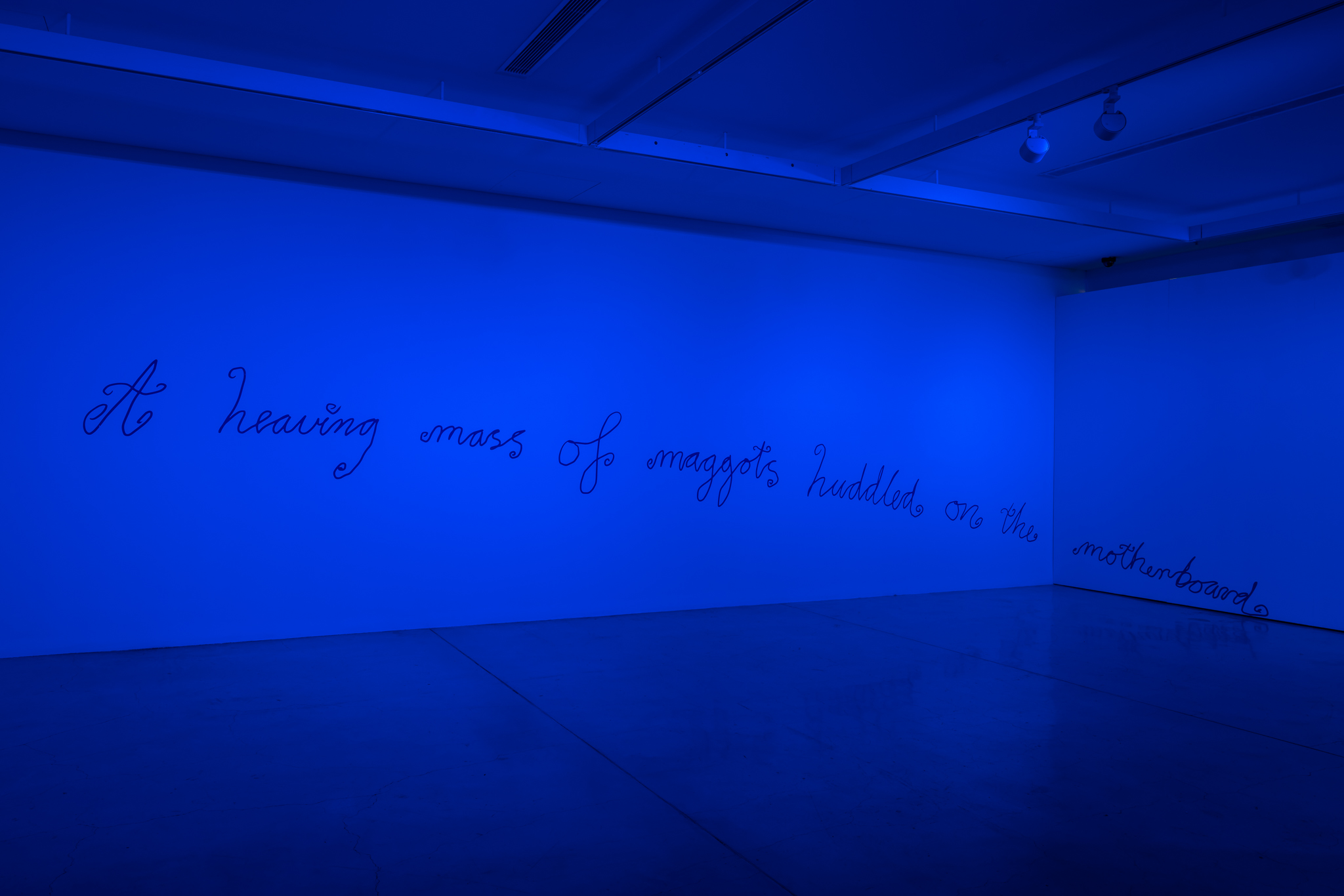

As you stand pinned in the space between the screens in front and the mesmerising voice behind, the space starts to compress. On the gallery’s far wall a scrawled text reads: “A heaving mass of maggots huddled on the motherboard”. You feel the bile start to rise.

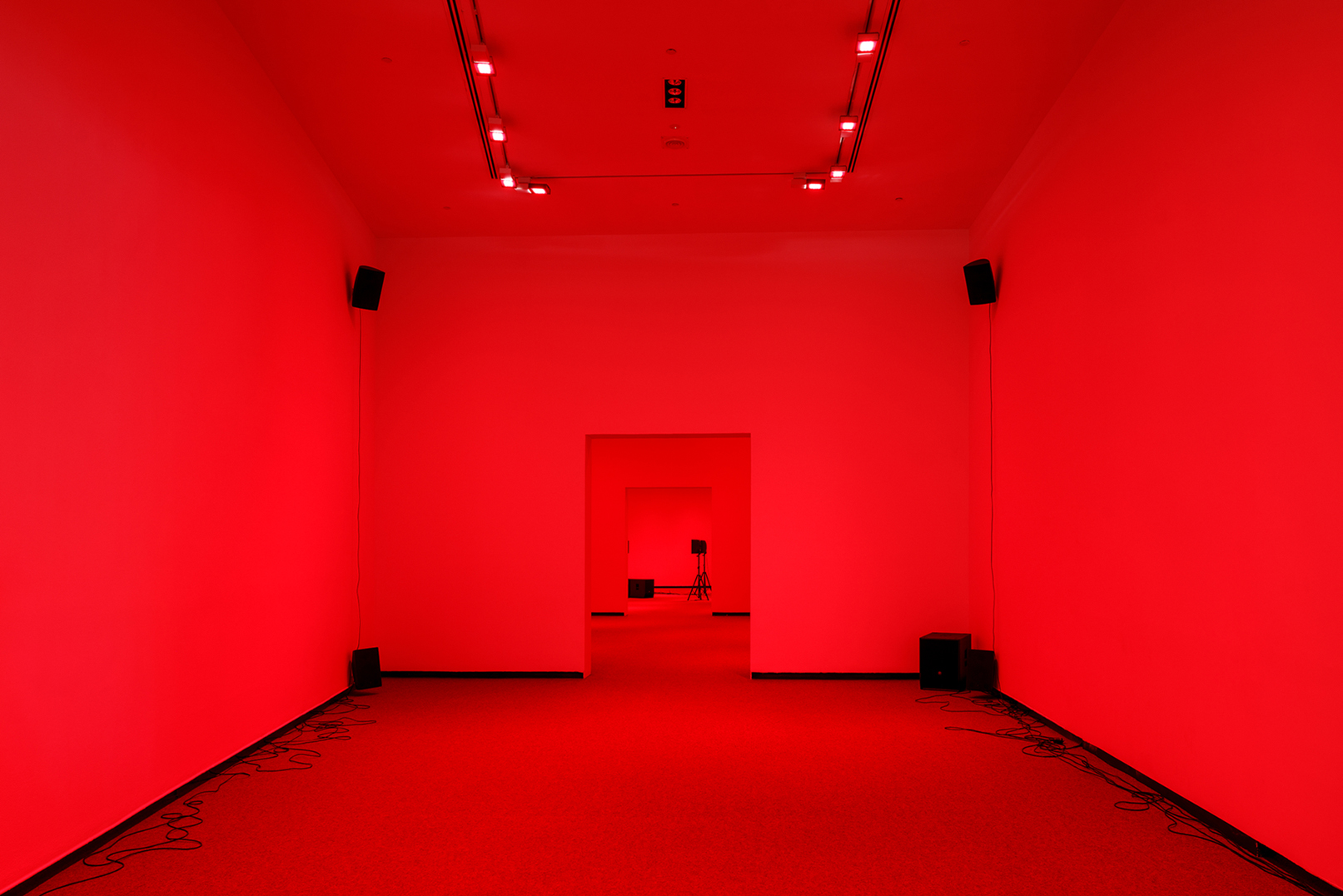

The year 2022 has felt like a key moment for the art of the bilious—artworks that seek to immerse the gallery visitor in an aesthetics of the corporeal, the revulsive, and the creaturely. A characteristic technique of the twentieth-century avant-garde and its successors (think Georges Bataille’s informe, Cindy Sherman’s abject series or Paul McCarthy’s performances), it is today being used by a number of Australian artists to tackle the disorientations of twenty-first century life. In Venice right now, for example, bad-boy guitarist Marco Fusinato is punishing visitors to the Australian pavilion with a wall of improvised noise, and a corresponding cavalcade of what he labels “fucked up images”. In Melbourne, meanwhile, one can still experience Meatus, an exhibition put together by artist-cum-curator Frances Barrett that bathes ACCA’s cavernous halls in a sea of red light and loud, abrasive sounds, accompanied by a rich imagery of worms, cavities and defecation. (Read Chelsea Hopper’s excellent review of this show here).

These three artists each deploy their abject aesthetics to different ends, and none of them does so lightly. McMahon’s Maggot, like Fusinato’s and Barrett’s productions, is a major artwork that has been gestating over a long period. The work is the output of an important new Artist in Residence program at UTS (the University of Technology Sydney), in which selected artists are invited to work in collaboration with a UTS researcher over a period of twelve months. McMahon, one of the two inaugural recipients (along with Amala Groom), elected to tap into the University’s expertise in Brain Computer Interaction, pairing with Dr YK Wang at the UTS Tech Lab. Dr Wang introduced McMahon to NextMind, a slick headset device that is able to detect the operations of a user’s visual cortex.

The likely future uses of this technology are predictably sinister—I note that Dr Wang currently has research projects with Lockheed Martin and the Department of Defence. Maggot, however, is not an attempt to simply critique or lay bare this future techno-dystopia. Instead, McMahon repurposes the technology for a more playful use—as a way for visitors to navigate a choose-your-own-adventure tale that plays out across the screens. At key junctures in the story the visitor is asked to make a choice by looking left or right; the device’s sensor then miraculously detects (via the visual cortex) the visitor’s choice and progresses the narrative.

In Maggot technology functions as an artistic technique, but also as a metaphor. The work’s narrative component tells the story of an erotic encounter between a self (a quasi-fictional version of McMahon themselves) and an other (“you”, the visitor). In McMahon’s striking prose (which recalls the uncanny techno-eroticism of Holly Childs) the self is figured as a computer, a machine that processes, files and is constantly “searching for something”. You, the other, are the maggot—a term of endearment, but also a figure of death and regeneration. As the work progresses, computer and maggot meet and become erotically entangled with each other in various ways, depending on the choices you make. In each case McMahon’s words hone in on the feeling of infatuation, of self and other crashing together in a euphoric mingling of warm bodies, fluids and breath. McMahon figures this feeling through the metaphor of a virus (a reference to the ILOVEYOU virus of 2000). The computer’s encounter with the maggot/other causes it to become infected, unstable, and eventually to crash with the abrupt announcement: “Restart!”

McMahon’s development of Maggot over the course of the past year was, of course, deeply impacted by covid-imposed lockdowns, which left the socially active artist stuck at a desk in front of a window, experiencing life only at a distance. It is easy to read the traces of this in the finished work—its yearning for love and intimacy, its generous embrace of the visitor, and the sense of panic and entrapment bubbling just below the surface.

In a public conversation with Frances Barrett last week, McMahon admitted that an earlier version of the work was indeed an attempt to grapple with their vexed experience of lockdown. In April, however, McMahon had a revelatory visit to Barrett’s Meatus. Standing in the midst of the exhibition’s immersive environment, McMahon was reminded of art’s capacity to viscerally affect the visitor, and to invoke new kinds of experience. It also reminded them that experience—especially McMahon’s own life experience—had long been a fundamental building block of their own practice.

Experience, of course, is not a neutral term. As thinkers from Kant to Paul Preciado have pointed out, experience (whether sensorial, affective or relational) is always given to us through predetermined frameworks—not only those of time, space and language, but also of gender and sexuality. Today the dominant framework of experience remains that of the autonomous, rational, straight white male (thanks a lot, Kant).

Maggot and Meatus approach the politics of experience with a shared set of strategies. Both make expert use of space, light and technology to create a specific gallery experience, one that directly engages and disrupts the visitor’s sensorium. Both projects also work with a similar set of carefully selected metaphors—the worm, the meatus, the maggot and the virus—that linger in the mind and carry the force of the work long after the visitor has left the gallery. This clever tropism speaks of a shared inheritance from the pioneering “merchants of slime” VNS Matrix, who similarly used an evocative imagery of body parts, viruses and fluids to communicate a feminist/queer vision of 1990s cyberculture.

Barrett and McMahon’s shared aesthetic of the queer informe, and their use of it to disrupt normative identity frameworks, is what separates them from Fusinato’s blunter, more macho approach. Yet within this shared space, McMahon and Barrett’s ultimate goals differ.

As Barrett has explained, Meatus aims to shatter the dominant framework of experience and thus open up a new way of engaging with the world. The exhibition’s first weapon in this quest is the “worm”—a model of collaboration and improvisation developed by Barrett, Brian Fuata and Hayley Forward, and demonstrated in the exhibition’s central sound piece, Worm Divination ((segmented realities)) (2020). The worm method eschews the single authorial figure in favour of a collective mass, which engorges received forms of language or identity and recomposes them into “sonic force”.

The worm is, in turn, an iteration of the exhibition’s master trope, the meatus. Meatus is a medical term that describes a passage from the interior to the exterior of the body. Barrett uses it as a metaphor for a new type of “listening” that occurs not via any one particular organ (such as the eye or ear), but rather via a sensorial system diffused across the body. Barrett and her collaborators conceive the exhibition itself as a kind of meatus, a set of tunnels in which light and sound are not so much seen or heard as felt.

Meatus’s objective, then, is to foment a radically new type of perception and subjectivity. Maggot, on the other hand, is more restrained and cautious. McMahon’s immersive installation does not seek to unleash the visitor into an unbounded utopian space, but rather fixes them in a carefully arranged apparatus. Even the work’s narrative, although replete with the language of disintegration and liquidity, is still parcelled out into a limited set of binary choices.

Maggot is not oriented towards a present or future moment of liberation outside the dominant framework of experience, but rather points to liberatory moments within it. The narrative of computer, maggot and virus described above rehearses the familiar Hegelian story of subject meets object, but with a twist. The incursion of viral infatuation interrupts Hegel’s progress towards enlightened subjectivity, and instead describes a self repeatedly consumed, disintegrated and reconstituted by a maggoty other—a computer that keeps restarting. The image of a recognisable self remains, not as a single autonomous figure, but as a string of such moments and memories that can be retrospectively strung together. This model of the subject as a product of autofiction has been at the core of McMahon’s practice for some time, and places them in dialogue with artists and writers like Andrea Lawlor, Juliana Huxtable, McKenzie Wark and Preciado.

The reason for McMahon’s softer approach to the self and experience is also perhaps technological. The NextMind device that McMahon uses suggests that perception has already been freed from the confines of individual organs and bodies, and is instead now situated in a space of neurological impulses and flows. A subject freed from the traditional frameworks of experience has therefore not necessarily escaped the forces of control and exploitation—but may instead have arrived at their most recent frontier.

Nick Croggon is an art historian, writer and editor based on Gadigal and Wangal land. He is Events and Programs Officer at the Power Institute, and is completing a PhD at Columbia University, New York.