Homologies of HOPE; Michelle Zuccolo: The Encounter; Alive Inside

Rex Butler

After twenty-eight years and some three-hundred pages, Robinson Crusoe finally gets off the island. It’s a moment for which Daniel Defoe reserves his happiest, sunniest, most straightforward prose—and, remember, throughout the whole long lonely episode Robinson always believes he will be rescued, never feels he is alone, is always convinced his sufferings have some higher meaning thanks to his newly discovered faith in God:

When I took leave of this island, I carry’d on board for reliques the great goat’s-skin cap I made, my umbrella, and my parrot; also I forgot not to take the money I formerly mention’d, which had lain by me so long useless, that it was grown rusty, or tarnish’d, and could hardly pass for silver, till it had been a little rubb’d, and handled, as also the money I found in the wreck of the Spanish ship.

And thus I left the island, the nineteenth of December, as I found by the ship’s account, in the year 1686, after I had been upon it eight and twenty years, two months, and 19 days.

Melbourne’s lockdown ended at midnight last Thursday, and the papers and television were full of images of young people out getting drunk, women having their hair done and old Italian men sharing espressos. But the art galleries aren’t open yet as I write—the authorities don’t regard them as essential services (as opposed to bottleshops) and obviously imagine them as more crowded than I at least usually experience them. Indeed, most commercial galleries I visit mid-week are not only like standing on an empty tennis court but playing a game by yourself.

The shows I’m going to review are all online, and they’re all in some way about what just happened—or didn’t happen because, if you didn’t actually catch COVID, then the thing was defined by a kind of absence. It’s as though life suddenly came to a stop and you were alive with nothing happening. You looked out onto the world as though still there but nothing and no one else was. You were somehow alone, even when you were with the few people you were allowed to be with. You had so much time on your hands, but nothing to do with it. You were like Robinson on his island—and one of the things I did in my lockdown was read all the books that worked off Defoe’s: J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island, Michael Tournier’s Friday, Joanna Ross’ We Who Are About To and even Michel Houllebecq’s The Possibility of an Island, although eventually his unrelenting misogyny got to me and I gave up—except that, unlike Robinson, the more I thought about it, the more I realised that no one was up there looking out for me or even looking out for us.

It’s strange how few galleries are showing COVID art or how few artists are making it. You’ve got to expect that in the years to come there will be all kinds of institutionally respectable curations of it—art and bullshit “wellness” here we come—and all kinds of philosophical reflections upon it. (Of course, even within the first year of COVID, Slavoj Žižek had written no fewer than two books on the subject, but that is like Mozart improvising upon one of Salieri’s uninspired tunes, sitting there grinning on the piano stool in the king’s palace.) But I was looking for COVID responses now and even for art—if we are going to attribute to it any magical, restorative powers at all—that somehow predicted what was about to happen to all of us: COVID art pre-COVID that, like a kind of God, might help us live better through it.

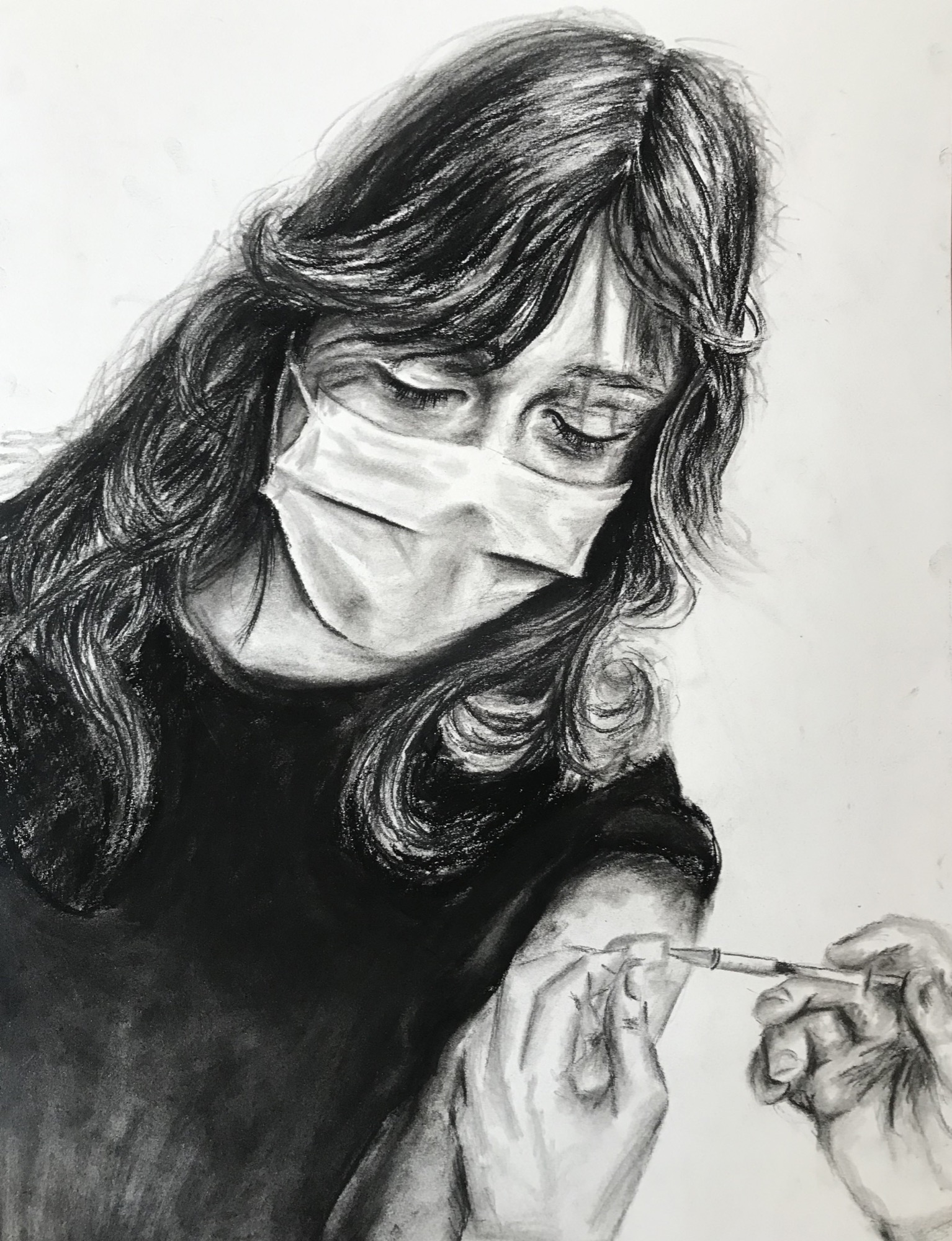

The one I’ll start with is the exhibition Faces of COVID, Lockdowns and the Places We Can’t Go on something called Artspace Kunstmatrix by Dr Amaali Lokuge, an Emergency Physician at Royal Melbourne Hospital. First of all, God knows how she did it while still practising as a doctor. Maybe it was a kind of therapy for her. And they’re actually pretty good. I have a thing about amateur art. I always go to the Hawthorn Art Society’s Annual Exhibition, a few suburbs from where I live. I find amateur art better or let us say less annoying, than about 80% of most contemporary gallery shows: the art is sincere, non-ironic, actually tries to be good (as opposed to so bad it’s good). It’s like art schools. About 80% of the young people who enter make better work in their high school submissions than when they leave. It’s just that the art world only wants the 20% whose work is better—and yes, I suppose better—than when they entered.

Lokuge shows a bunch of kids getting vaccinated, her colleague Emma West, a young boy getting a COVID test, her kids doing homeschooling, the holidays she’s not taking and her cuddling her partner at night. The charcoal drawings and paintings are made with the same care and attention, the same sense that there is no outside audience looking on, as I figure she exhibits when she’s all masked and gloved up in the ICU ward. If a smart, properly “wellness”-concerned institutional art space wanted to do a show on COVID in the years to come, they could do a lot worse than start here.

Now we come to the artists: first the commercial art world outliers of West End Art Space in the group show Homologies of Hope, which, to quote the press release, aims to “celebrate the creativity of our artists during these uncertain times, with works that inspire in them a sense of renewal, hope and potential”. The works are arranged in a grid online with the artist’s name on top. They’re all for sale, and maybe the stand-out ones are Sue Rosalind Veseley’s would-be Baroque ceiling paintings, Fran O’Neill’s David Reed–like squiggles and Giordano Biondi’s architectural wood carvings. Most of them are softly coloured and delicately painted, as I suppose they think they have to be if they’re to offer us some solace. Maybe they’re trying to be something like one of those awkward elbow bumps that idiots like Boris Johnson likes to inflict on other people. The one I responded to most strongly was Monique Lacey’s Purified (2021), which looked a bit like a COVID face mask taped to the wall on sale for no less than $5500. Eat your heart out Jens Haaning, I say.

And now we come to the hipster commercial gallery. No sentiment or comfort here, no homology of hope or anything like it. It’s Geoff Newton’s Neon Parc’s response to COVID, Alive Inside, in which he has rounded up a bunch of works that originally had nothing to do with COVID and made it seem as though they do. That’s the prophetic power of art and the marketing ingenuity—and maybe even desperation—of the present-day COVID-struck gallery dealer. But it’s undeniably clever and itself a premonition of what curators are going to do in the years to come when they take a deeper dive into our culture to show how artists already knew what was going to happen centuries after their death. (And, speaking of Daniel Defoe, you can’t beat his 1722 A Journal of the Plague Year about the bubonic plague that swept London in 1665, which I also tried to read, before my iPhone got the better of me, just like almost everyone I know, and I gave up).

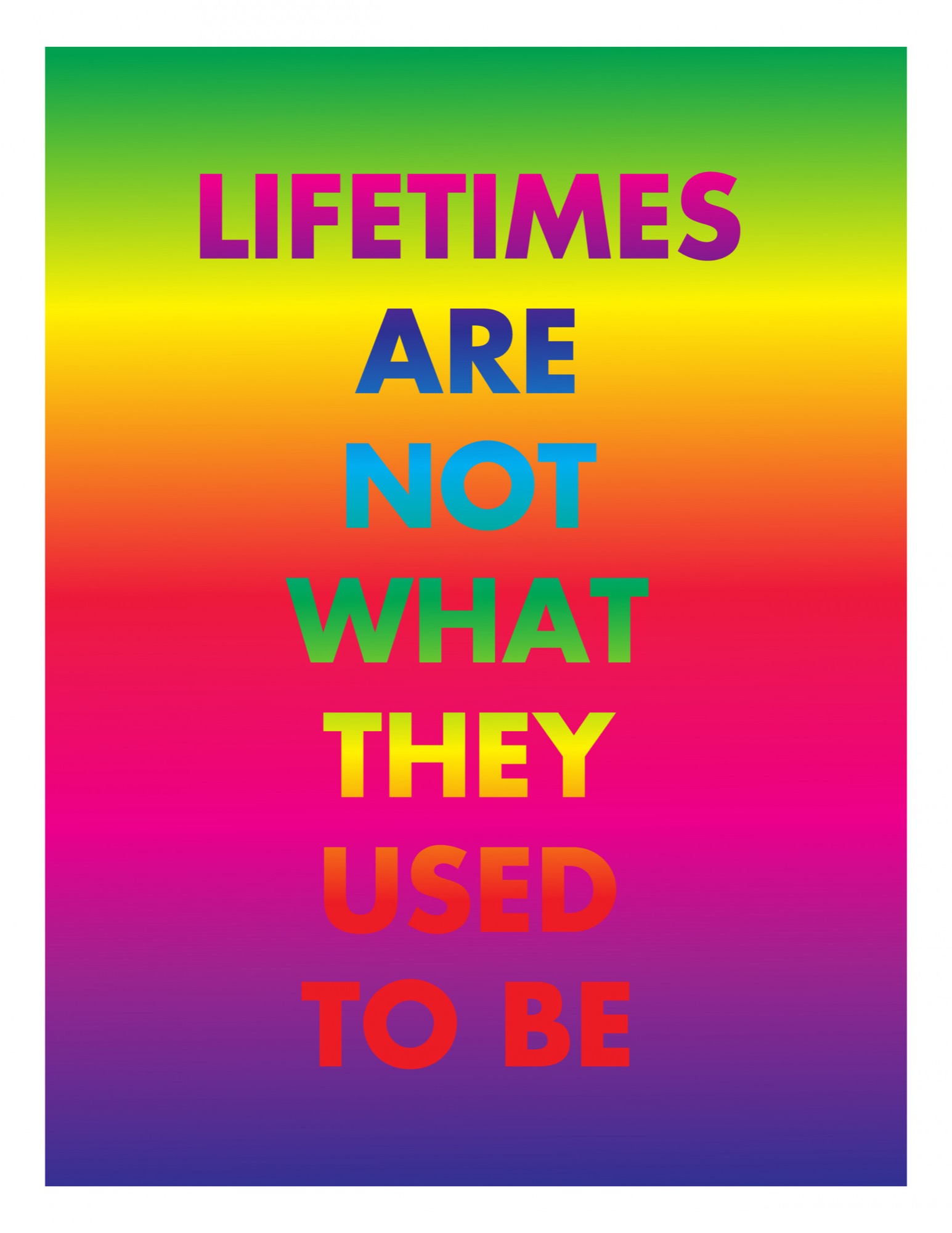

The undoubted standout of Newton’s show—good curating here—was David McDiarmid’s AIDS-era posters, Do You Really Want to Hurt Me (1994) and Lifetimes Are Not What They Used To Be (1994). The disjunction between their dazzling rainbow colours and their ominous messages never fails to shock—I have a distant memory back in Brisbane of Scott Redford repainting McDiarmids Jasper Johns–style in a more suitable grey and black. And now they also prophetically look like a sort of screensaver or text message. Maybe that is how the grim reaper will soon reach us when he doesn’t look like Johnny Depp in a Tim Burton film.

Newton also detournes a 2018 work by Darren Sylvester, The End, a C-type print with the words THE END laid across the earth as seen from outer space. I think it’s the end credit you see in a Universal Pictures film and in my maybe flawed memory, it’s what comes on the screen at the conclusion of Hitchcock’s Vertigo, just after Scottie stares off into space at the top of the belltower and the nun who has run up the stairs, causing Madeleine to fall, rings the bell and crosses herself.

The other Sylvester work that Newton includes is Horizons (2019), a photograph taken out the small oval window of an airplane with sunset-struck clouds glowing pinkly outside. The set-up is dark and claustrophobic, reminding us that we’re trapped in our seats for the duration of the flight with nowhere to go and not much to do. Clever Darren already knew that COVID was brewing somewhere down on the ground, ready to take over the world.

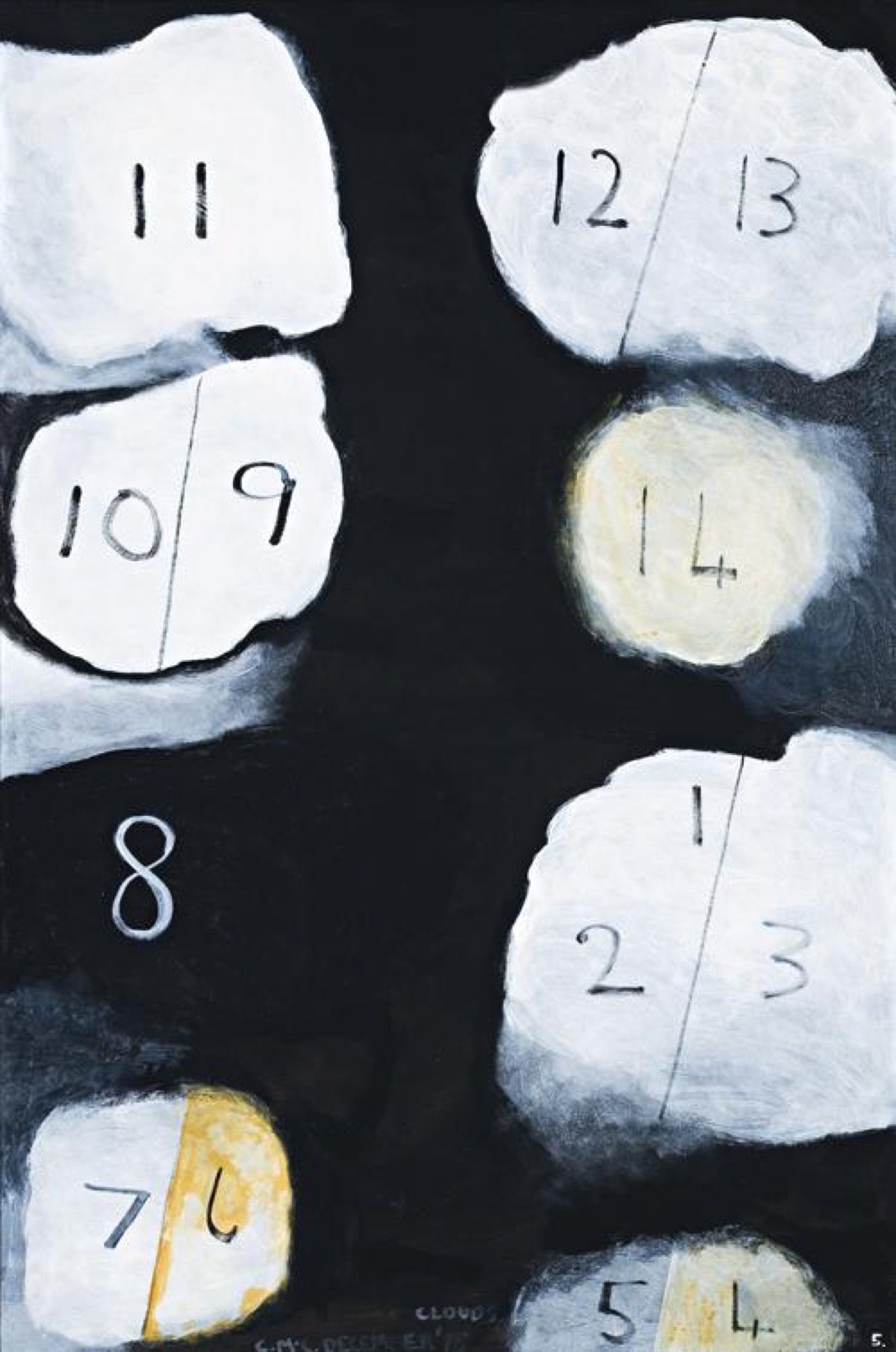

I was asked last year—wasn’t everybody involved somehow with art?—to nominate a work that I thought best spoke to what seemed to be happening. It was before masks, before the vaccine, before the endless lockdown when people seemed mysteriously to be infecting other people. I chose a work from my all-time favourite Colin McCahon’s 1975 Cloud series, with its atmospheric sphere of thick white paint rising up against a dense black background. It’s kind of like a big cough in an otherwise dark room that is mystically illuminated, not any more with Christ’s divine light—McCahon was, as we know, a kind of wandering Christian—but with death. McCahon’s painting suddenly seemed as ominous as hell in the light of what was happening, and it’s absolutely the image I’d use to encourage people to wear masks if I were New Zealand’s Chief Medical Officer (which, luckily for everyone concerned, I’m not).

But the work I now see as a premonition of what was about to happen is Michelle Zuccolo’s Augury (Self Portrait) (2019), currently online at Bayside Gallery. The work was actually the winner of the Rick Amor Self-Portrait Prize and shows Zuccolo, who is a secondary school art teacher, staring leftwards, that is, backwards, at a strange cut-out silhouette (maybe a palette), which looks like it’s resting on a painting turned backwards. Apparently, it’s an image of the artist’s “mind journey” as she looks for inspiration in the everyday objects around her, but I naturally want to see it as something more oracular than that. That silhouette is not a palette, but actually destiny that lies beneath the surface of the picture like the back of the canvas we see at the bottom. It’s the feline—or maybe bat-like—face of COVID staring back at whoever looks at it, daring you not to blink.

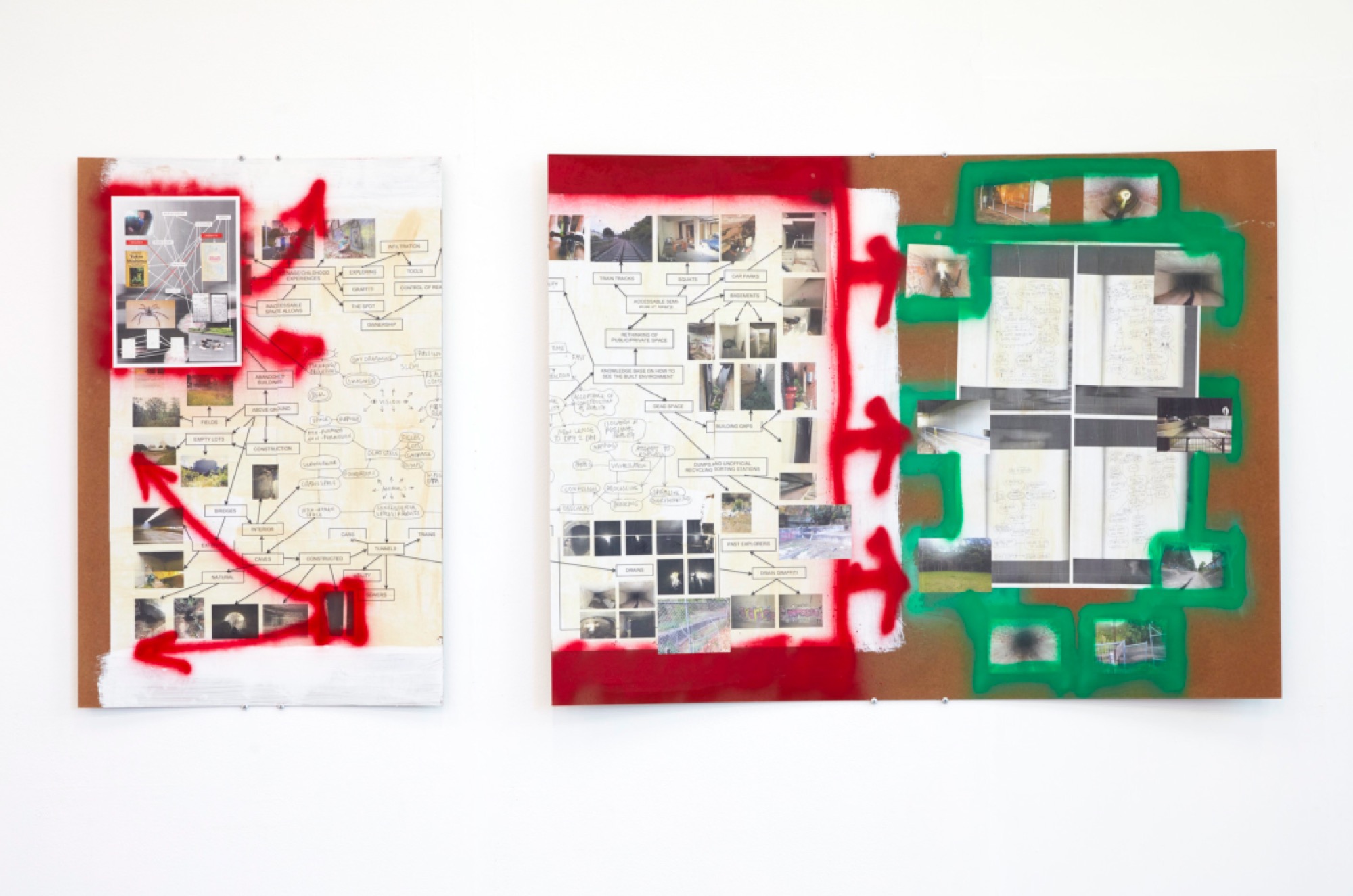

OK, maybe too much. Actually, if I really had to pick just one COVID-prophetic work of art and something that has haunted me since the moment I saw it, it’s Rory Maley’s Thinking Maps 2012–20, which was originally shown in the Monash third-year graduating show in late 2020. (All potential conflicts of interest declared. Actually, I don’t think I have any. See the remark above about art schools.) It’s an amazing confessional masterpiece that seemed like my own deepest secrets transcribed directly onto canvas.

The work is something like a giant pinboard that puts together grimy photos of weird interstitial spaces (carparks, laneways, the sides of buildings) along with circled words for various mental states (confusion, thinking, processing, spiralling), almost like the diary of a homeless person looking for places to sleep at night and wondering what has happened to them. All the various parts of the work are connected by wavering hand-drawn arrows looping around them as though to form some kind of miniature world or ecosystem known only to the artist.

It struck me with the force of revelation. It was a magnificent image of the fragility of our world and the possibility that at any moment one could lose everything and be forced to survive alone and without resources. Call it the fear of suddenly losing all one’s possessions, the fear of global climate catastrophe, the fear of all of one’s personal relationships suddenly being cancelled.

I felt it all acutely. It was like Maley was somehow speaking to me alone. In my aimless daily walks around Ashburton during lockdown, I couldn’t help looking over my neighbours’ fences to see how other people lived. Mostly—this being middle-class Melbourne—they kept up appearances, mowed their lawns, tended their gardens. But every so often you saw the house of somehow who had lost it: barricaded inside, the grass grown high, weeds sprouting, junk scattered everywhere. And I impossibly identified with them. I could see myself living in their house.

Likewise, as I walked next to highways and railway tracks, I became obsessed by what the French sociologist Marc Augé calls non-lieux: non-places. Small parks at the end of dead ends that no one needs, the embankments that run beneath noise barricades. They seem spaces where you could escape, hide, sleep rough and no one would notice you. And somehow during my long, pointless COVID-day walks I grew mesmerised with these invisible spaces, somehow seeing in them some kind of a correlative to my own—and I suppose everybody else’s—situation.

I don’t know how Maley saw or felt all of this too, but I am going to add him to my list of Robinson Crusoe readings. Maybe the real person who died in COVID was God, and we realise that without him, her, or it we are all alone on our islands, all looking on at a world we cannot join, cannot help, cannot intervene in, waiting to be rescued.

Yes, Defoe saw the end of lockdown alright:

I was now to consider which way to steer my course next, and what to do with the estate that Providence had thus put into my hands; and indeed I had more care upon my head now, than I had in my silent state of life in the island, where I wanted nothing but what I had, and had nothing but what I wanted.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.