Robert Smithson: Time Crystals

Philip Brophy

The survey of works, models and materials in Robert Smithson: Time Crystals at MUMA is a fascinating opportunity not simply to view Smithson’s work, but also to reflect on his methods and theories. The exhibition draws upon Chris McAuliffe and Amelia Barikin’s deep and longstanding interest in Smithson and the legacy of his notions of planetary and geological temporality in shaping physical construction (and hence, sculpture as we knew it). A key feature of the exhibition is the framing of the MUMA site with two darkened chambers, each exhibiting a projection of a landmark land art film: Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson’s Swamp (1971). Their conjoined audio lightly floats throughout the other five chambers.

This review will consider that floating sound.

Spiral Jetty is an exemplar of the museographic sub-category of cinema usually referred to as the ‘artist’s film’. Taken at its prescribed value, the ‘artist’s film’ exhibits a belief in artists bringing to the medium of film something more, other, different or even essential about cinema and moving image-making. It’s a Romantic dream, more in line with Courbet’s heroics than McLuhan’s specifics. Mostly, artists’ films and videos betray a shallow understanding of cinema history and form, and the complex cultural positioning of movies and their purpose. However, through this core contradiction (a delusion in many contemporary instances) the ‘artist’s film’ can evidence a rich multivalence in many an artist’s conceptual rhetoric.

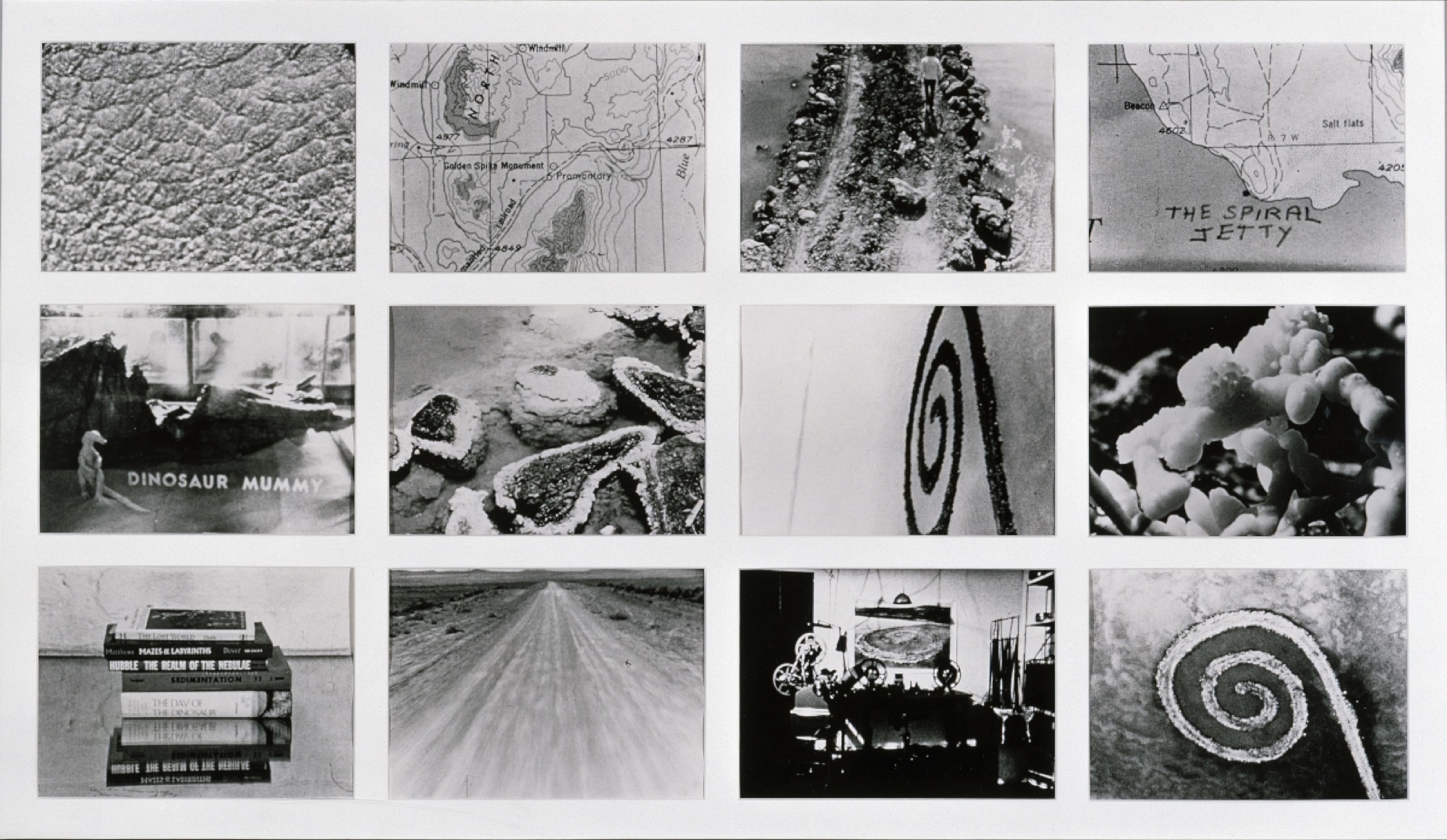

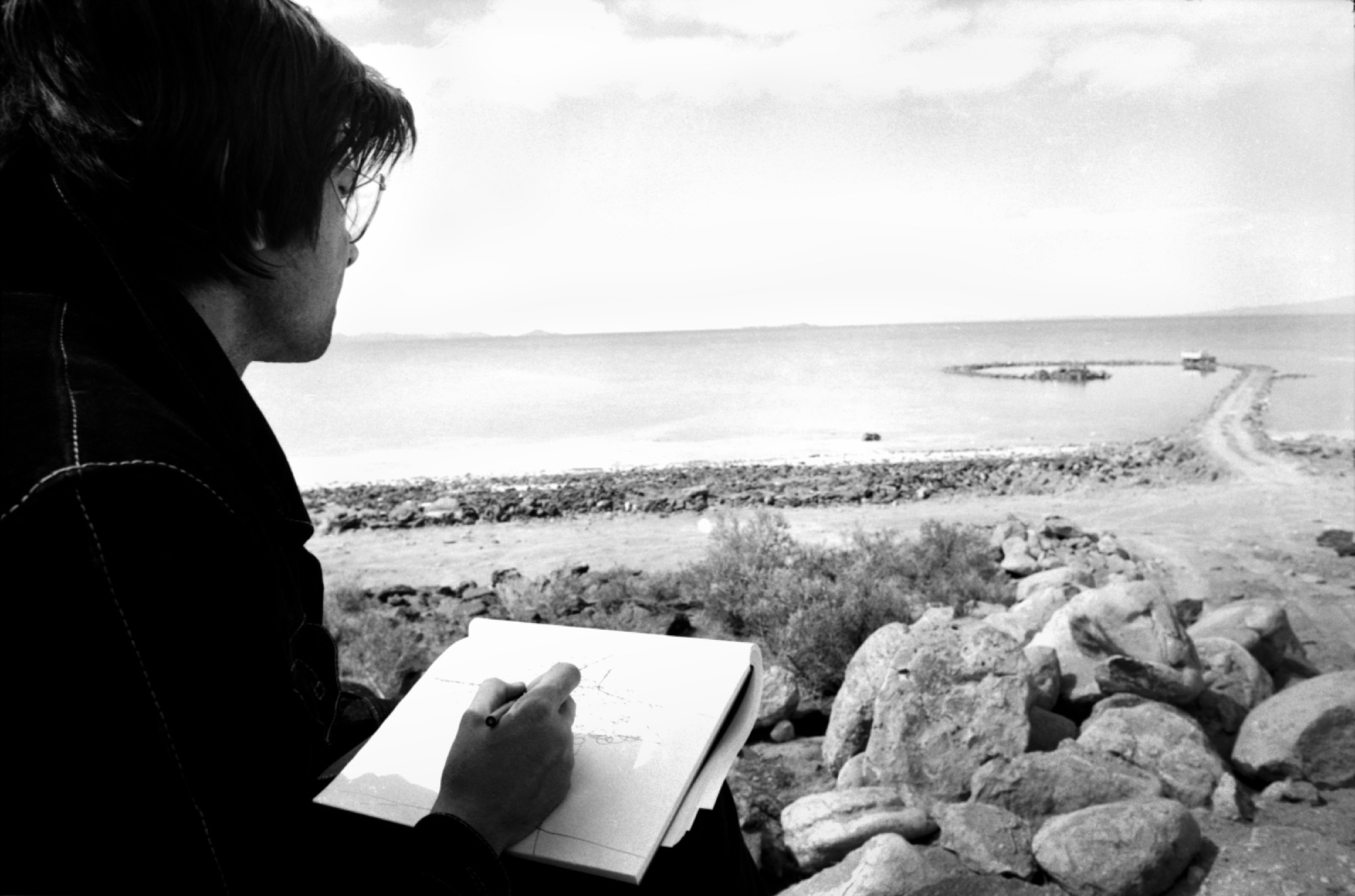

Spiral Jetty is mostly a systematic documentary of the eponymous land art construction sited at the edge of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. The film’s bulk records the planning and making of the work, plus a literal and optical survey of the new land construct engineered by Smithson. As this artwork continues to morph ecologically, politically and historically as a site of entropic environmental endeavour, the film provides a sense of the work’s physical gestation and final sculpting. Like much large scale land art since, the recording of its procedural manifestation clarifies the conceptual priorities behind such projects. Smithson’s ruminations on the filmmaking process (especially its post-production) angle an insight into film’s self-preserving archival function. Through documenting Spiral Jetty, he characterized film as “an archeozoic medium” and the edit suite’s mechanics akin to “a time machine”.

One can also reflect on the state and status of the ghostly living archive of Spiral Jetty as it is animated once more in a museum setting decades after its initial encoding. The filmed footage captures—or, more so, stages—Smithson as a figure in his own landscape in ways that can reorient a counter reading of conceptual art in general as a return to Romantic ideals of the landscape. Smithson haunts Spiral Jetty like the chilling Rückenfigur of Caspar David Friedrich’s dark pastoral settings. More than half of Friedrich’s landscapes painted between roughly 1810 to 1830 feature a diminutive figure (sometimes two) facing away from the viewer. This faceless persona could likely be a projected fusion of Friedrich and his young brother—who died before his eyes slipping into a lake whose ice cracked under their feet. For Friedrich, the ground literally swallowed humanity, in the process forging a notion of landscape as a non-humancentric life force. Standing before Friedrich’s paintings—none of which are monumental in scale—is a haunting experience that can empty the self if one is so disposed.

Smithson never evacuates himself from Spiral Jetty. His back faces us because we are positioned to follow him, like a Vernian explorer of new worlds in modern art’s own reconfigured fin de siècle: the sixties. While the intention might be for Smithson to position him as a reference for scale to diagrammatically indicate the human’s relation to massive swathes of land, the film performs a counter measure in its alignment of the artist with intrepid and ingenious explorers. The film might be ambiguous about this, but conceptual art is rarely ambiguous: it often trades in po-faced statistics in order to disarm a poetry-hungry audience. Smithson’s voice intones statistics in the film’s opening, placing himself in the centre of the artwork and reciting compass readings and geological assessments of what lies before him in each positional sector. It’s a de-humanising tone, born of an American vernacular recitation which is audible in the Beat poetry of William Burroughs and John Giorno through to the minimalist oratories of Robert Wilson and Robert Ashley.

But in the film, this voice is textually omnipresent. Positioned in post-production as an extradiegetic aural effect, its ‘voice from beyond the frame’ correlates to the godly directives heard by Moses and countless schizophrenics since. Smithson’s body is visibly located in the film like a Letraset ‘figure’ pasted onto the architectural plan; his voice floats above, in the realm of architectural vision. Over-extended helicopter shots reinforce the latter. Smithson’s ‘voice-over narration’ is less a comment on narrative proceedings and more a declaration of principles of existence, as if he is directing his own world-making. At the film’s conclusion, the echoic Vulcan clangs matched to shots of archaeological artefacts evoke an imaginary ‘big bang’ of worldly creation. Smithson might be linking his land art to non-expressive action, but the film’s audiovision implies he is engaged in a supra-creative act by shaping earthly matter. Ultimately, Spiral Jetty bears witness to a Promethean feat; Smithson’s own voice is its testament.

Smithson’s notes on the project (edited by Nancy Holt) notably reflect on the filmmaking process. His comments on Spiral Jetty the artwork and Spiral Jetty the film blur to an extent, suggesting that the film afforded him a critical perspective on his project (cinematographically due to the helicopter shots; semantically through the montage), which is voiced by the soundtrack. Visual artists are often amazed and excited by the post-production of a film’s soundtrack, and Spiral Jetty grapples with the extended passage of reconstruction that all films undergo, as editors and directors slavishly ponder, query, interrogate and transform the original directorial, performative and cinematographic intentions now frozen in celluloid’s unforgiving amber. Yet it is in the mysteries of audiovision that all films audit the textual chaos of their signification. The rumbling bulldozers and the droning helicopter smear the film with an industrial aural patina, rendering in sound if not ‘napalm in the morning’ at least diesel fuel atomised across the desolate Utah terrain. Importantly, these seeming contradictions, I would argue, deepen the value of Spiral Jetty, and afford a repositioning of it beyond the authorial ascription so often insisted on by the ‘artist’s film’. Thus, Spiral Jetty is ultimately a signpost of land development, the creation of added-value real estate, and the attendant noise of site construction.

The voice of Smithson also features in the collaborative film he made with Nancy Holt one year later, Swamp. Vocality sears the surface of this film. Holt holds the 16mm camera, and moves forward into the marshy terrain goaded by Smithson off-camera to “go straight”, “keep going”, “go further”, etc. Smithson recorded the sound “wild” onto a reel recorder (that is, un-synched to the camera, using the system known then as “crystal sync”, which employed quartz for temporal stability in the recorder’s speed as developed for Seiko watches - but that’s another story). This sound was then appended to the ostensibly silent footage.

It’s a fascinating social document. The eyes of the wife being told to see what the husband declares, Swamp is more of a domestic power struggle than a visual pondering of naturalised non-site messiness as a micro-environment of spatiality. Like the blaring industrial machinery of Spiral Jetty, Swamp’s audiovisuality captures the mismatch between godly directives and mortal behaviour. Smith’s vocabulary of penetration could be lifted straight from a porno shoot. Here, we are now perhaps deviating too far from Holt and Smithson’s artistic concerns and the MUMA exhibition’s curatorial frame, but the film’s status as archival document lends it to readings in concert with other concurrent documents. As the camera timidly cuts a path through the swamp and reeds, it documents Holt and Smithson’s joint struggle to traverse a natural domain limiting human egress. It also collapses metaphor and metonym in filming Holt’s bodily POV as directed by Smithson’s narrational POV, for this is precisely what happens in the deployment of hand-held cameras in terror and horror films. The increase in sexualised violence in the cinema throughout the sixties can be traced across near countless examples of woman frantically wandering through impenetrable nature: forests, woods, deserts, swamps. The camera held in the hand—like an artist wields a brush—has always been there to capture the sensational thrill of her descent into the brutish non-human centric world, where man becomes animal and woman becomes meat.

It’s pretty difficult to watch Swamp and not think of this—despite the fact that the film also perfectly documents Holt and Smithson’s filmically rendered proposal of the swamp as a ‘geo-chronic’ site. Inside the bracketed dark zones of the MUMA exhibition, one could be transported to these other worlds of supreme archaeological statement and sculptural redefinition—for which Smithson and Holt deserve their historical footholds. Their soundtracks aid in reminding one of that which exists beyond those worlds.

Philip Brophy writes on art among other things.