Murray Griffin: A Life and a Journey

Jarrod Zlatic

Opened in 2021, the Banyule Council-run Ivanhoe Library and Culture Hub has a rich history to draw upon. The Heidelberg area is something of a palimpsest through which a disparate history of Australian art can be read. There is of course the Heidelberg School and the near-by Heide farmhouse, both of which provided successive definitions of ”Australian” art. There are also lesser-known figures such as modernist painter Lina Bryans and her artists’ colony the Pink Hotel in the late 1930s (a base for Ian Fairweather, amongst others). A little later in the 1960s there were Jim and Rene Davidson, who ran the Aboriginal and Pacific Art Gallery out of their Ivanhoe home. The Davidsons were among the first commercial dealers and promoters of Yolŋu bark paintings, important in gaining the interest of art institutions in Indigenous painting. To speak of art shown in domestic spaces is also to re-call the recently departed backyard space Guzzler. The contemporary house-gallery par excellence, it was nestled in Rosanna (from it’s beginnings, Heidelberg is now “at the end of Australian art history,” as Memo’s own Cameron Hurst has written of Guzzler elsewhere). The Ivanhoe Library and Culture Centre have tapped into this local history, complementing typical council gallery fare with a series of solo retrospectives on Heidelberg-based modernist print-makers-cum-painters: Napier Waller, Edward Heffernan and now, in their latest exhibition, Murray Griffin: A Life and a Journey.

The majority of the exhibition is dedicated to Griffin’s printmaking. Amongst the first Australian artists to use the linocut for fine art purposes, he developed in the 1930s his own approach to colour prints via the reduction method: portions of the original relief are gradually removed for use with different inks. This method results in rich, multicoloured works, and even Griffin’s earliest works are impressively confident and accomplished. His prints carry a debt to the flat, decorative quality of Japanese prints and even more so the work of Austrian printmaker Norbertine von Bresslern-Roth. Griffin’s zoological studies of birds—bowerbirds, herons, ducks, magpies, owls, pelicans, parrots, and so on—make up half of the thirty or so prints here. The predominance in the exhibition of these bird prints, which were seen by Griffin in primarily commercial terms, tends to downplay the more creative aspects of his work. While dynamic and attractive on an individual level, the orthinological studies here tend to blur together when presented en masse. They do provide an opportunity though to see the degree of control Griffin achieved over his complex print process. The gradients and highlights of an early print here such as Magpies (1936) are subtle and sure, but Griffin achieves an impressively precise detailing with Two Cockatoo’s (1969), looking more 3D than flat.

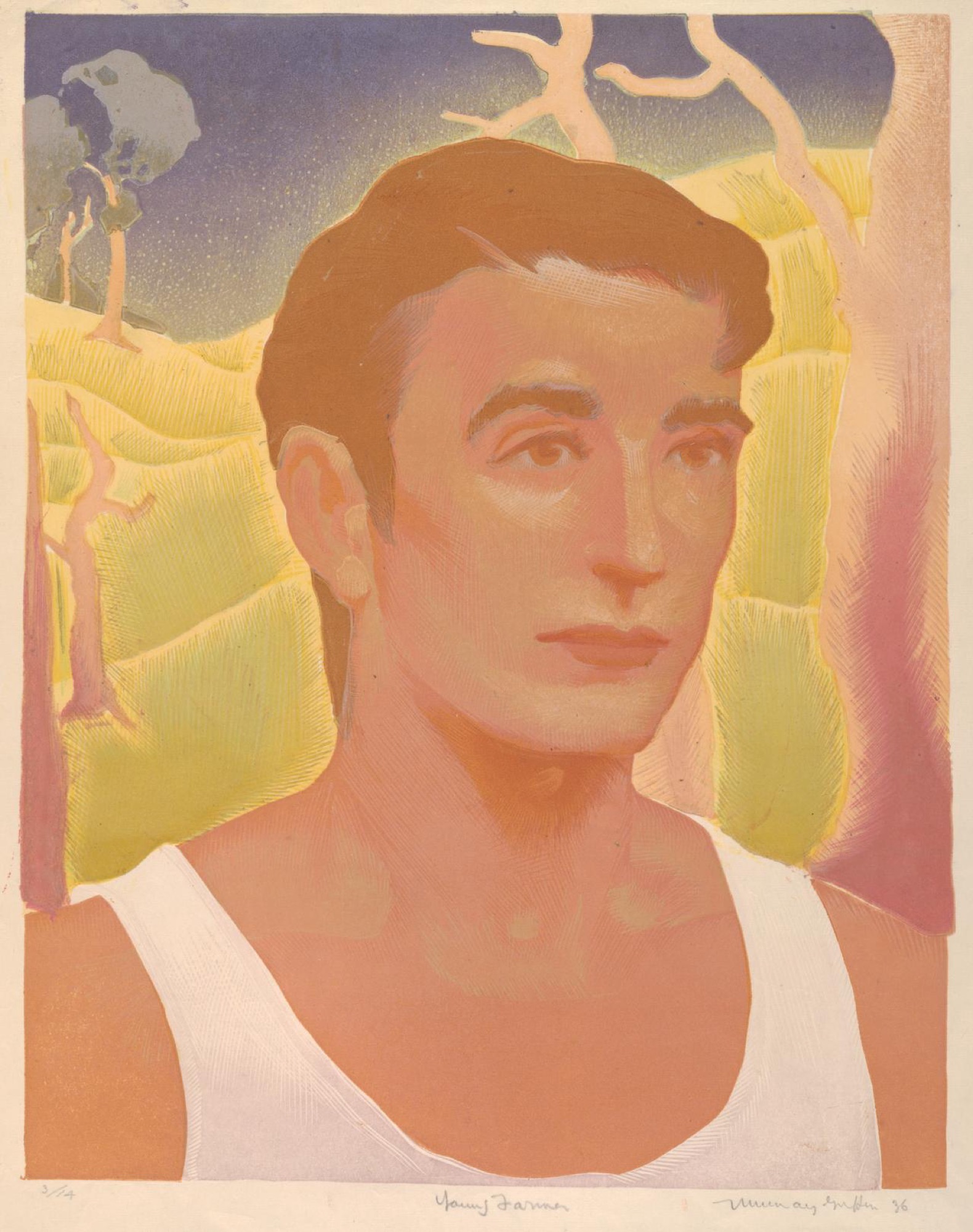

The most engaging prints in the show are those where Griffin grapples with more symbolic content. They transcend the mere decorativeness of the commercial prints, and seem permeated by his Theosophical beliefs (he remained a devotee of the writings of Rudolf Steiner throughout his life, introduced by the architects of his home, Walter Burley and Marion Mahony Griffin). There is an ethereal quality to Young Farmer (1936), a striking portrait, iconic in its arrangement. Sunburnt skin and eucalypt trunks are a washed out pink, the pastureland is a kiwi green. It could easily be mistaken for a 1980s Tin Shed or Australiana-laden Redback Graphix pastiche rather than the real thing, a relic from the highpoint of Anglo-Australia. A similar intensity is captured in Burning Mountain (1966) with the towering Mansfield hills at biblical proportions in glowing red tones. Also included are Griffin’s last major series of prints produced in the late 1960s, The Journey. His most esoteric works, they are an explicit depiction of his Theosophical beliefs. Large, perfect bodies are twisted and askew, wracked by elemental forces. Dynamic lines cut across gradients of turquoise, emerald, and ruby red. These prints are surprisingly redolent of the times in their obscure yet vitalist energy, suggestive of then contemporary hippie-era graphics.

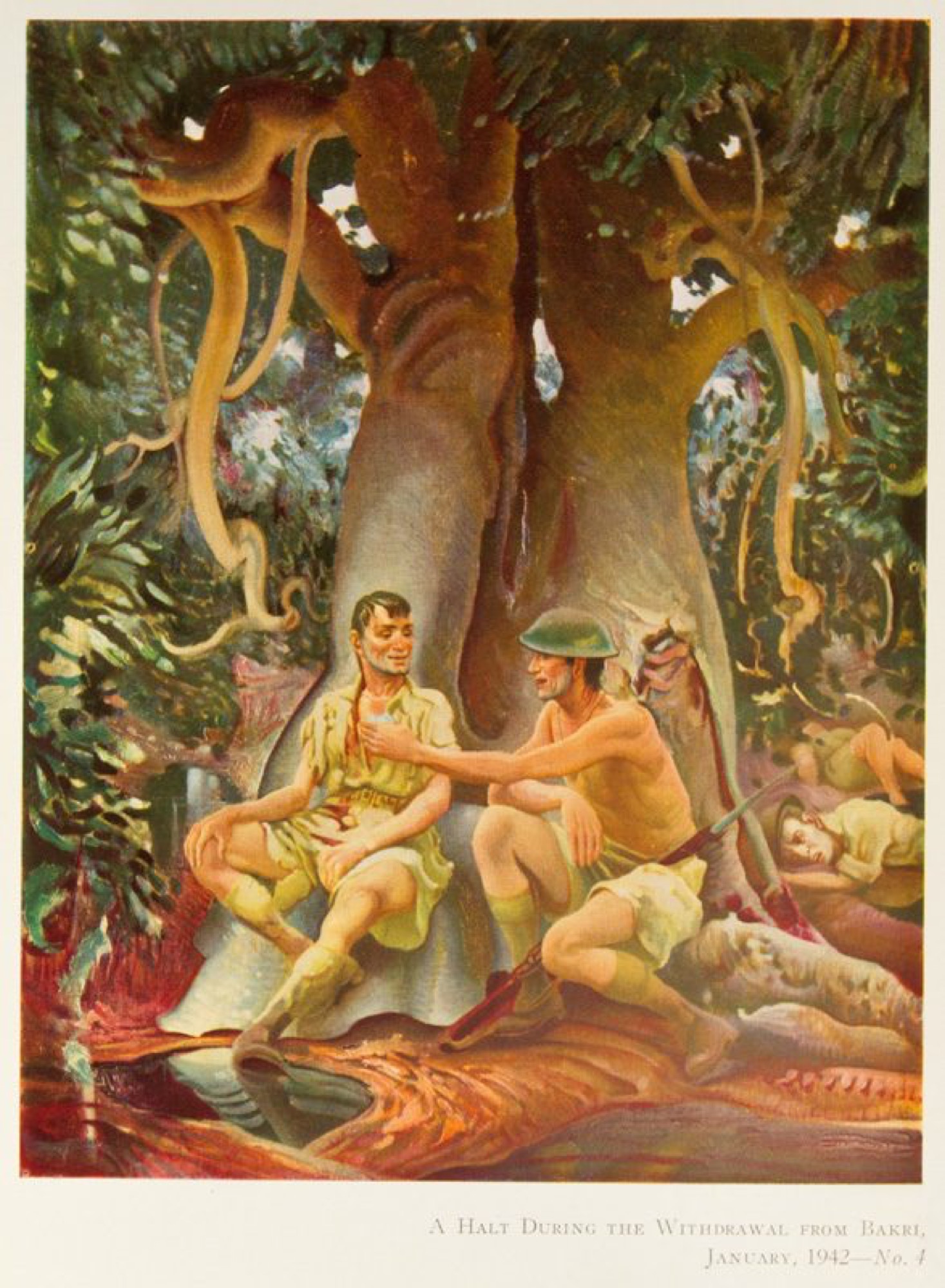

Griffin’s interest in colour extended to his recollections of the Changi prison camp, where he spent four years. Beyond the suffering and misery of internment, Changi was still “beautiful.” Griffin recalled the “rich glowing contrasts of colour, heavy massive foliage, grey twisting tree trunks curving through the air in mellow heat and stabs of brilliant colour to excite the senses.”

While in Changi he continued to make artworks with improvised materials, depicting scenes of both brutality and banality. These included a series of revealing paintings documenting combat and interment in Singapore, represented here via a reproduction of A Halt During the Withdrawal from Bakri (1942) in an old catalogue that is included in a vitrine of ephemera. The few actual works in the show from Griffin’s time in confinement are portraits, notably Soldier with Thompson Sub-Machinegun (1941–1942), a large charcoal sketch of a rather brutal and powerful-looking soldier. There are some oddities: a small sculpture of a wounded woman on a stretcher carved from a wooden table leg, a tiny linocut of a jungle road in vivid fluoro inks. Otherwise his time as a war artist and prisoner is represented via assorted memorabilia: letters, postcards, photos, army cards, etc.

A professional and well-assembled show, it remains at the curatorial level a council heritage exhibition focused on a life-long local resident. Working clockwise, the prints and paintings are mostly hung chronologically. Apart from the biographical texts that divide each of the four walls, the accompanying wall texts have been somewhat lazily sourced from elsewhere. There is a solid but pedestrian quality befitting the anonymous council curation. (I had to complain about the restricted opening hours, which were introduced at short notice, to even find out the name of the curator, who is not listed anywhere online or in the promotional materials.) As such there is little art-historical enquiry. The exhibition reiterates Griffin’s well-established reputation as a printmaker; his painting remains an adjacent and less important aspect of his art. Yet Griffin always considered himself first and foremost a painter. He spoke of his prints as an extension of his paintings, their precise layers of thick ink informed by the way he would apply paint to a canvas. His beginning was as a painter, and he continued painting after he became too frail to operate his printing press.

Altogether though approaching Griffin’s wider painting practice is somewhat difficult in the exhibition, given the selection on offer here. They are mostly unsold and undated works from the family’s own collection, taken from the second half of Griffin’s career. Excepting two late works, they are not the strongest examples of Griffin’s post-war painting and come across as bland and undistinguished. His palette at this point abandoned a naturalistic range of brown, green, and yellows and was increasingly imbued with a pink hue that suffocates these works. You have to look fairly hard here to find traces of Griffin’s sensuous use of paint—thick though not suffocating, almost like plastic—subtle combinations of colour, and soft, curving forms that sometimes have a churlish, almost hallucinogenic quality.

The selection is doubly disappointing as the Ivanhoe Library and Culture Hub is probably the ideal venue to re-assess Griffin’s painting. His debt is a paradoxical combination of so-called “Australian impressionism,” intimately tied to the Heidelberg area, and it’s opposite in post-impressionism. The critic Basil Burdett in his 1938 essay ‘Modern Art in Melbourne’ for Art in Australia included Griffin, but prefaced this with the acknowledgement that “many will quarrel, no doubt, with the inclusion.” Griffin, while modern, was not strictly modernist. Burdett admitted that Griffin, unlike other contemporaries, was equally an “Australian impressionist” painter as he was a modern one. Whatever deviations from established conventions Griffin explored in his paintings, they were not so radical as to arouse hostility, and critics throughout the interwar period noted the imagination and vigour of his work. Even Arthur Streeton, who was dismissive of modern art, wrote extremely favourably of Griffin during the 1920s and 1930s.

Griffin’s beginnings as an artist coincide with the beginnings of “Australian painting” when the work of the Heidelberg School became consolidated into a popular, national model. It seems Griffin internalised these emergent tropes of Australian landscape painting during the brief period where it lay uncomplicated and unchallenged with no alternative or rival model. The paintings in the exhibition are successful at least in demonstrating this with depictions of shadowy thickets of eucalypts, fruit gardens, old churches, workers, timber farm buildings, and rolling vistas. Griffin remained dedicated to this vision of the landscape that remained prior to subsequent breaks in the iconography of the genre, and across his life he continued to paint en plein air what was left of semi-rural Heidelberg. Griffin’s paintings carry forward this brief moment in the 1920s, before Australian pastoral painting came to be criticised as repressive and restrictive (though we might tend to see it today as banal more than anything). The reactionary character that the cliches of the Australian landscape genre eventually accrued, the supposed fascism of the genre as argued by Bernard Smith, could be so only once there was something to react against.

Griffin’s faithfulness to landscape painting tends to obscure his exploratory approach. Early on he was an indirect student of artist and pedagogue Max Meldrum, falling into the extended circle of Meldrumites that gathered at the home of art critic Mervyn Skipper near-by on Mont Eagle. Griffin embraced the tonalist approach to colour, but grew restless with the Meldrum circle’s lack of interest in design, which he described as their “look and put” approach to painting what was directly in front of them (the de-personalised, quasi-generative nature of Meldrum’s method).

More important was the friendship Griffin formed while at the National Gallery School with fellow student Francis Roy Thompson. They regularly painted together around Heidelberg and on holidays in Mansfield, holding two-person exhibitions together through the 1920s and 1930s. At some point Thompson in particular became interested in the post-impressionists, especially Van Gough. This may have been relatively early, possibly when he travelled overseas in 1923. Griffin and Thompson softly embraced reductive and expressive techniques in their landscape painting, which owed something to these modernist approaches. They had little interest in the abbreviated space and broken brushwork characteristic of other Melbourne painters such as William Frater who mostly gravitated towards Cézanne, and their painting remained, by the standards of the time, stylistically ambiguous.

Unlike Griffin, Thompson’s work became explicitly modernist. Thompson had travelled to England in the early 1930s specifically to study modern art practices at the Westminster School of Art, and his approach to design and colour became increasingly free. His rural scenes were distorted by an ecstatic expressionism that verged on abstraction. Griffin remained living in Heidelberg in relative isolation, while Thompson eventually settled in Adelaide in the 1950s, joining Dorrit Black’s Group 9, and was later included in the landmark 1961 exhibition Recent Australian Painting in London. Griffin’s painting remained relatively subdued, though continuing to make progressive work within the constraints of the genre. His earlier painting especially has a flexibility that is not dissimilar to Elioth Gruner, although much less restrained and impassive. While Griffin was certainly a parochial artist, his negotiations of local genres and techniques (Streeton, Meldrum) with a selective engagement of international trends suggest he was not a provincial artist per se.

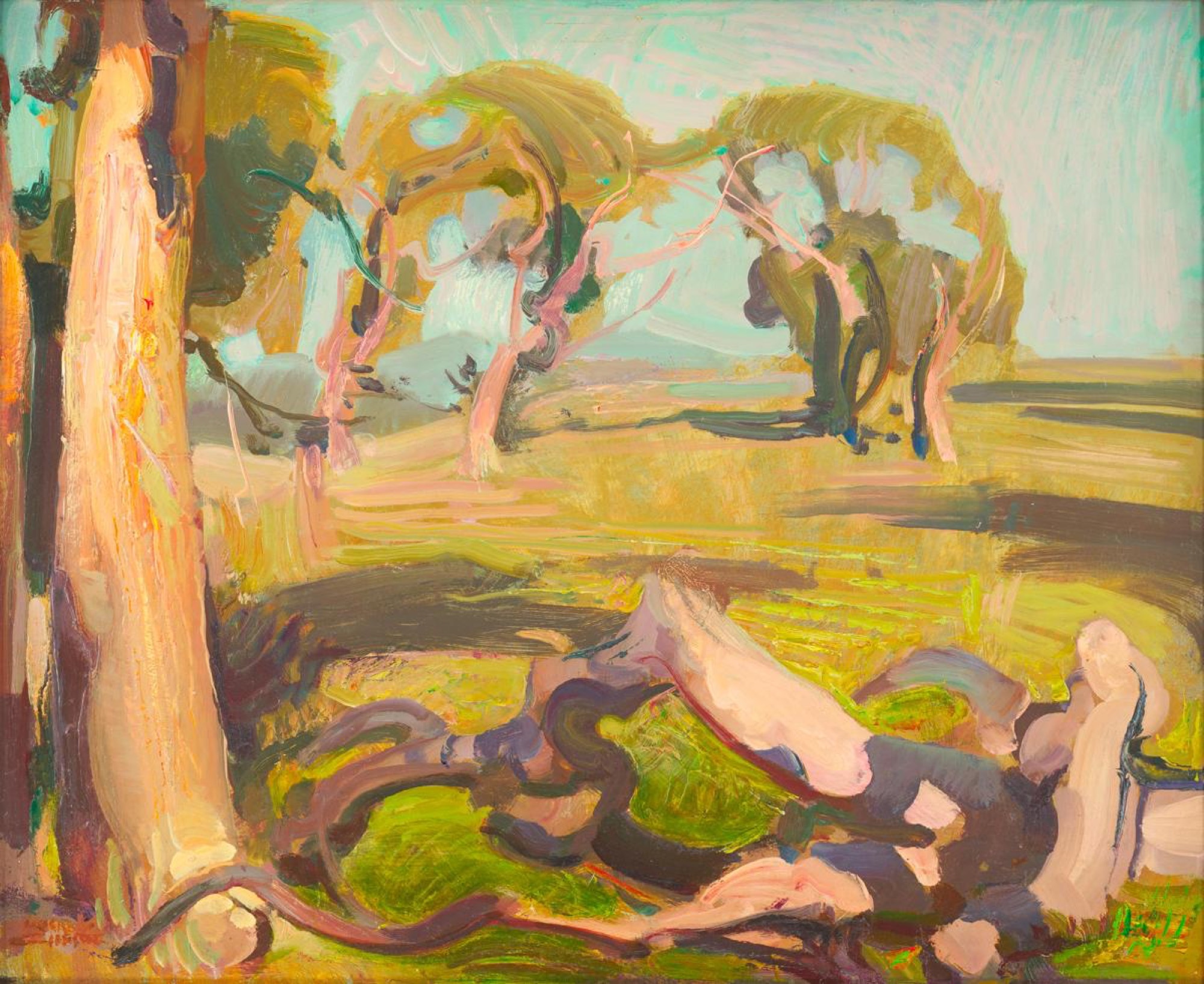

The most satisfying paintings in the show are two works from late in his career after he abandoned strict landscape painting. As Griffin grew older, he increasingly depicted either remembered or ideal landscapes. He moved from long-range views of hillsides and fields to painting amongst the trees, using these scenes as backdrops in an on-going series of works he titled The Journey. Griffin populated these landscapes with stockmen and pastoral workers, and they formed allegories for his Theosophical beliefs. There is little sense of realism in these paintings, and they incorporate a quality of fantasy and whimsy. An untitled and undated work (it in fact lacked a label, as several works did when I visited) has the fleshy quality of Griffin’s eucalypts translated into human form, with a huge, lumbering pagan figure seen deep within the Arcadian bush. The figure peers upwards into the trees as if looking for a bunch of grapes. In lesser hands these works could easily come across as clunky or kitschy. Yet there is a strange, melancholy elegance, especially in The Journey (undated), which is hung looking out onto the foyer. We see there a youthful, windswept stockman lost amongst the gums. It is like a theatrical set piece, with man and tree taking on shared proportions and forms. Bathed in a late afternoon pink, the only hint of the fabled golden summer is in the baby blue sky that pokes through the twisting eucalypt grove.

This fading afternoon could be applied to Griffin himself. He lived into his 90s, until 1992, and was one of the last people alive who could remember a Heidelberg that still resembled the pastoral depictions of the 1880s. Although the paintings on show here are imperfect examples, we might even say that Griffin himself became a living memory for the Heidelberg School in his dedication to its precepts. He carried forth an image in which Australia was imagined via Heidelberg. In painting these final imaginary works, it is like Griffin was capturing one final afterimage of the blinding light of this fading moment of Australian art. His point of gravity was never elsewhere; he was ultimately uninterested in fighting Heidelberg’s mythic pull.

Jarrod Zlatic is a writer and musician from Melbourne.