Machine Listening, a curriculum

Benison Kilby

Machines have ears. Calculating and extractive, they record and identify sounds, monitor populations, environments and even the health status of individuals. So what exactly do these machines hear? And how are the sounds they collect instrumentalised? These are some of the questions explored in Machine Listening, a curriculum, deftly curated by artist Sean Dockray, legal scholar James Parker and curator Joel Stern for Liquid Architecture. The program was launched on Zoom and streamed to Facebook and YouTube over the course of three evenings in early October as part of Unsound Festival. Framed around distinct problems and approaches to audio surveillance, each of the sessions brought together a diverse roster of artists, musicians, activists and academics from across the globe, many of them veterans of their respective fields. Growing out of their earlier exhibition, Eavesdropping, at the Ian Potter Museum of Art in 2018, the multi-format endeavour is complemented with interviews, experiments and texts.

Machine Listening, a curriculum is described by its organisers as “an investigation and experiment in collective learning”. The idea that the educative process can be a form of artistic or curatorial production has an extensive but relatively recent history. The unrealised Manifesta 6, Copenhagen Free University, Tania Bruguera’s Cátedra Arte de Conducta and Anton Vidokle’s unitednationsplaza are just a few of a growing number of projects that manifest an engagement with pedagogy. They show that such projects are often diverse in terms of their methods, aims and scope. As Machine Listening, a curriculum demonstrates, when used as a curatorial strategy, pedagogical models shift exhibition making from the presentation of discrete works of art in a particular place. Instead, these models act as a process of dissemination that often emphasises the creation of new instances of sociality through reading groups and, in this case, online gatherings. Projects of this type are often weighted against more orthodox places of education. Due to the ongoing drive to neo-liberalise higher education, most recently in Australia through staff and funding cuts, as well as the doubling of fees for humanities courses, these kinds of mobilisations are particularly important. The degree to which Machine Listening, a curriculum is independent of the objectives and strategies of tertiary institutions appears to be complicated though, when one considers that it was developed in partnership with Melbourne Law School and ANU School of Art & Design.

Over the past several years, there has been a growing and interconnected use of online syllabi by social justice movements. Often these take the form of a series of links to scholarly texts, news reports and audio-visual media, mostly collated through a collaborative process in response to a political situation. This phenomenon can be understood as part of a long lineage of media production by social justice movements to encourage processes of political subjectivation and consciousness raising. The educational aspect of Machine Listening, a curriculum was instigated by Sean Dockray, who has a long-standing commitment to self-organised and non-commodified forms of knowledge sharing. Working collaboratively, he initiated AAAAARG, Telic Arts Exchange and the Public School in Los Angeles in the 2000s. For Machine Listening, a curriculum he developed a new piece of software called Sandpoints with Marcell Mars of Pirate Care that can store and organise texts in ways that are stable, easy to access and free. This infrastructure enables the collective editing of online syllabi and is designed to be used by others.

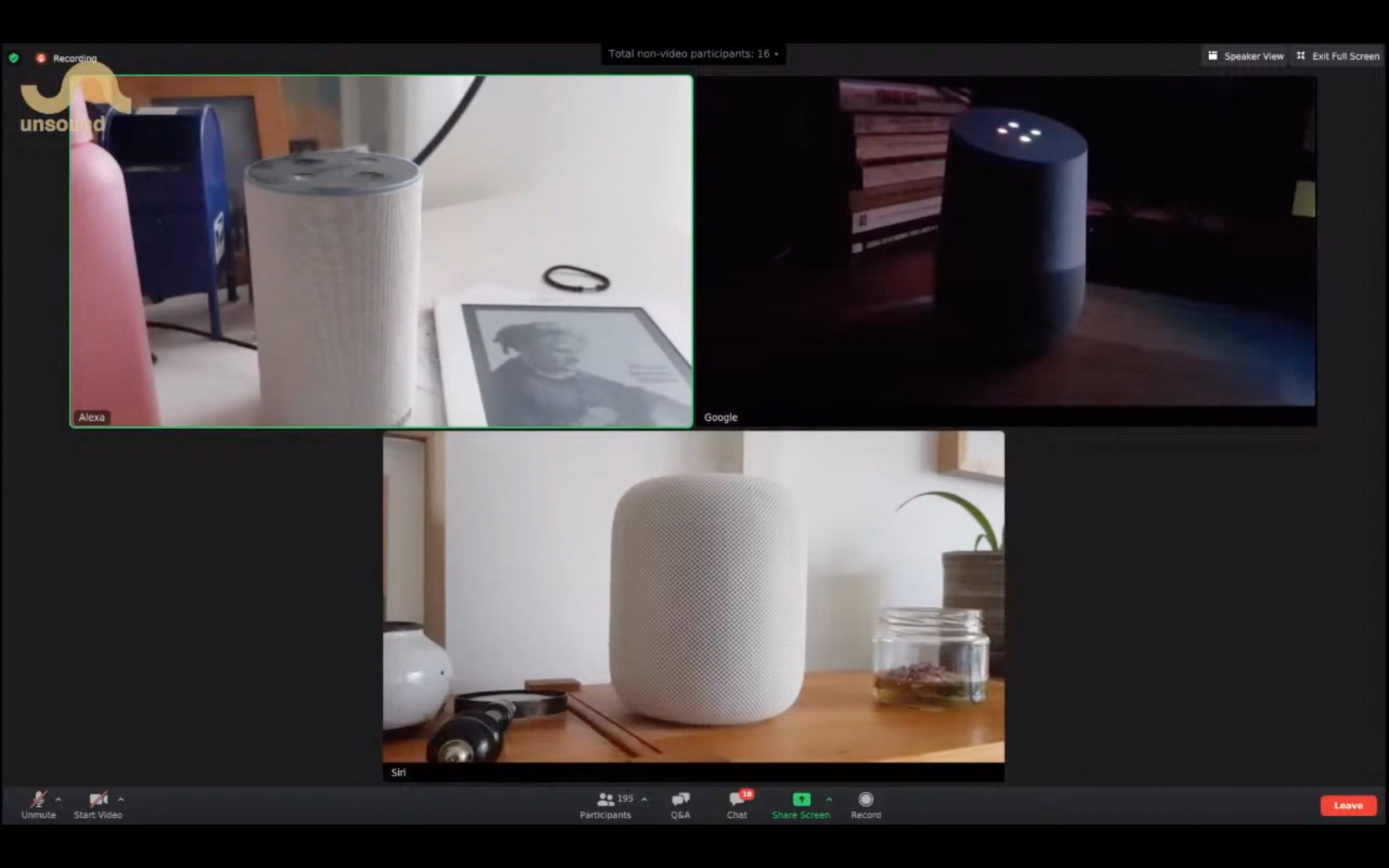

The second largest private employer in the US, Amazon, has doubled its profit since the Covid-19 pandemic began. It sells a voice activated speaker called Echo that monitors you with seven directional microphones once you place it in your home. This device connects you to the cloud-based voice assistant Alexa, whose objective is to “make your life easy” by learning your habits, needs and desires. “People know we are listening all the time”, Alexa announces opening the first Machine Listening session with Dockray’s work, Always Learning, Everywhere… (2020). Framed by individual Zoom windows, Siri, Alexa and Google sit, their impassive cylindrical forms undisturbed over the course of their animated ten-minute conversation. Each of these objects is a corporate-looking grey tone designed to blend seamlessly with the contemporary home, which appropriately now doubles as an office due to the pandemic. Their gendered voices further entrench the division of labour around domestic and service work, as they reflect on existential and psychological issues that point not only to subtle and diffuse forms of social control, but to the blurring of boundaries between the human and non-human, conscious and non-conscious. Dockray’s web-browser essay, Listening to the Diagnostic Ear (2020), which introduced the audience to an online dataset being developed to diagnose Covid-19 and speculated on the possibility of a future market for fake cough results due to the need for workers to continue working precarious jobs, was another highlight of the program.

Following a presentation of his video, Deviant Chain (2019), taken from a larger installation created with Alan Segal and Victor Shepardson, the Canadian artist and musician Stefan Maier read from Intelligent Life (1981–82). A significant inspiration for his own work, the sci-fi “media-opera” is by the pioneering sound artist Maryanne Amacher (1938–2009). The opera consists of nine episodes designed to be performed simultaneously for television and radio. As of yet, it has not been made. Instead we see the script’s type-written pages presented on coloured card. Set in 2021, the plot concerns Supreme Connections LLC, a music, research and entertainment company, following the working lives of its leading employees. It introduces “ear tone” music, high-volume timbres used to activate onto-acoustic emissions, tones generated by the listener’s inner ear. Amacher imagines compositions created by combining these biological sounds with synthetic ones. While her media-opera is far from uncritical towards potential developments like these, at one point it poetically speculates that in the future artificial intelligence will enable us to hear as a reindeer hears, prefiguring questions around the ways machine listening technology will impact on our own listening and subjectivity.

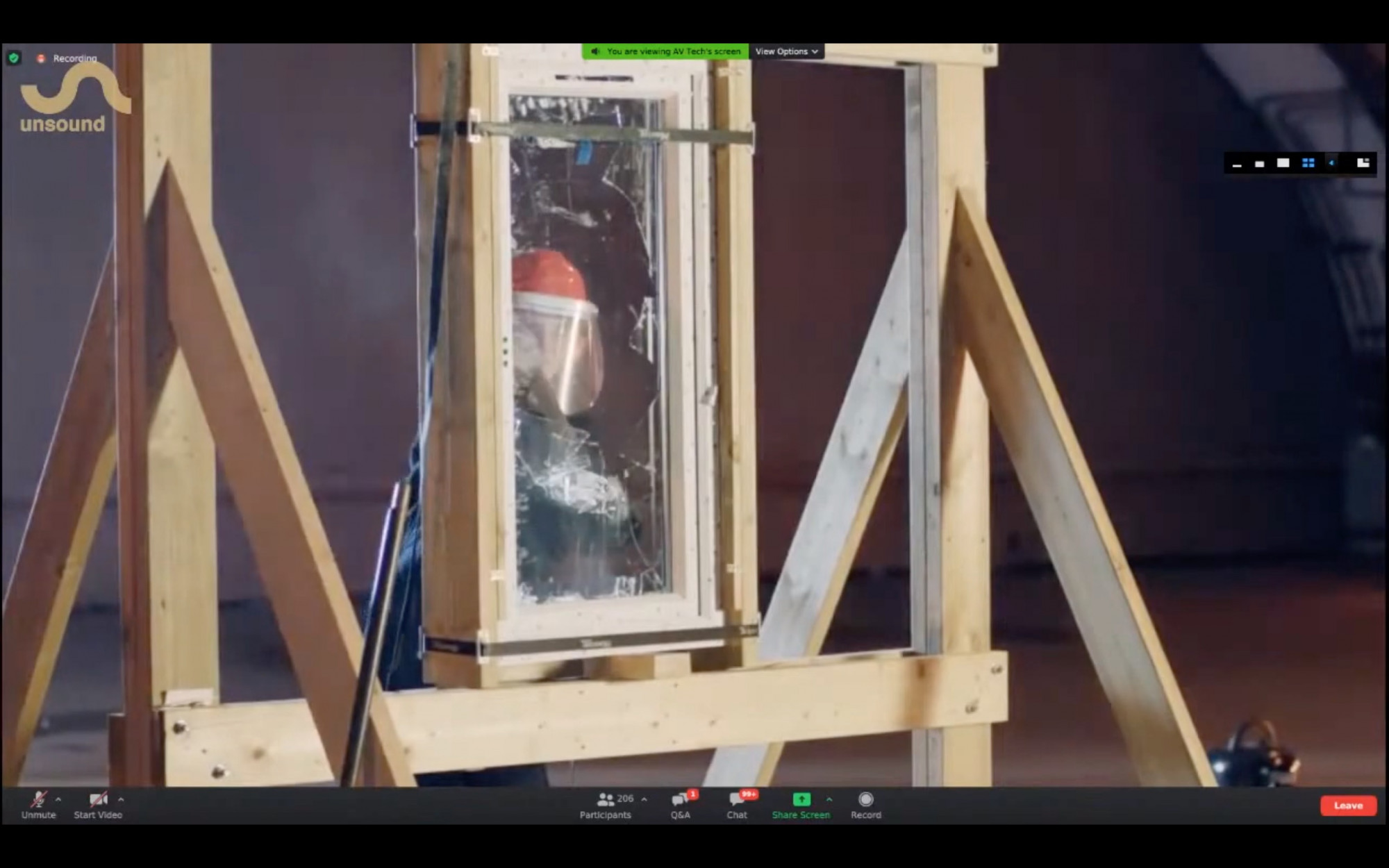

Well into the first Machine Listening, a curriculum session, a female worker in dark blue overalls enters a cavernous aircraft-hanger. “My name is Anastasia”, she states, beginning Hito Steyerl’s video The City of Broken Windows (2018), which like Maier’s work is from a larger installation. The camera surveys panes of glass lying in two ordered rows on the floor. A few moments later a visored employee smashes a window, which has been strapped to a custom-made scaffold, with a mallet. The slowed-down sound of falling glass creates a disturbing melody as it tinkles mechanically through my laptop’s speakers. Documenting a group of research engineers employed by the company Audio Analytic to train computing systems to recognise the sound of windows being smashed for use in the production of home security systems, Steyerl’s work demonstrates that even the so-called immaterial labour of those who work in the surveillance and tech industries can be both monotonous and physically demanding. As one researcher comments, the novelty of this normally anarchic action quickly wears off: “The third time it becomes work”.

Framed principally as a thought experiment, McKenzie Wark’s Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse? suggests that the Marxist confrontation between the proletariat and capitalist may have been eclipsed by the rise of a class who own and control information: the “vectoralist” class. She contrasts this group, who are able to harness information for profit, with the hacker class, who produce novel forms of information. Thinking through class relations in a slightly different way, a number of presentations in the final session called attention to sounds that are normally considered insignificant: the ping, the cough, the breath. The sounds that would normally be edited out. As Shannon Matten suggested in the closing discussion, these insubstantial sounds were given a new meaning, taking on the status of an aural underclass and becoming a metaphor for those who do not have the right to be heard, those who are not represented in datasets. It was also in the final session that the troubling of conventional educational roles was most clearly put into practice, when after Andrew Brooks’ lecture performance, which mobilised the plea “I can’t breathe”, a catchcry symbolising disregard for black lives used in ongoing Black Lives Matter protests, attendees were unmuted and invited to participate in an experiment in collective breathing.

Machine Listening, a curriculum shed light on advancements in computational listening, showing how artists, musicians and thinkers are interpreting and subverting these developments. Opening up debates and raising awareness around the listening capacities of artificial intelligence, as well as the impact these technologies have on privacy, governance and subjectivity, there may be no more apposite climate in which to explore the questions Machine Listening, a curriculum raises. With many people across the globe now living in isolation due to Covid-19 lockdowns, we are increasingly compelled to use digital platforms to connect with others. The pandemic has forced curators, artists, educators and audiences to move online and in so doing supply tech giants with a fresh and exponentially expanded set of data. For this reason, questions around online forms of pedagogy, communication and collectivity and the ramifications that these activities entail in terms of data extraction now feel more pressing than ever.

Benison Kilby is a writer and curator whose research is focused on Marxist and feminist approaches to art history and curating.