Light and Darkness: Late Modernism and the JW Power Collection

Neha Kale

Bridget Riley has always understood the relationship that exists between our sight, our bodies and the world. In a 1967 interview with the art critic David Sylvester, the renowned British op artist remembered climbing a mountain in France. The heat transformed the land around her into a shimmer. Back in her studio, the artist painted Static 3 (1966), a constellation of black discs on a white field. As I stand in front of it, six decades on, the tiny ovals wobble. I feel off balance. The more time I spend with the painting, the less sure I am of where my edges are.

Static 3 is on display as part of Light and Darkness, an elegant exhibition at the Chau Chak Wing Museum showcasing seventy works from the University of Sydney’s JW Power Collection, acquired between the 1960s and 1980s. Entering the Museum’s fourth floor Ian Potter Gallery, all stark lines and moody lighting, I was a little nervous. Earlier this year I’d experienced, for the first time, a bout of vertigo that erased a delusion I hadn’t realised I’d harboured: that my senses were objective. That my eyes were a failsafe source of evidence. The experience of being visually unsettled had somehow imprinted my body. My perception felt newly fragile.

The catalogue, edited by the show’s curator Ann Stephen, informed me that the Power Collection was a consequence of a bequest by the trailblazing artist John Wardell Power. After relocating to Europe, the medical graduate joined the 1930s Paris avant-garde, and became among the first Australian-born painters to experiment with cubism. With his bequest, Power hoped to introduce “the people of Australia to the latest ideas and theories in the plastic arts”. In its earliest days, the Power Collection focussed on op art, kinetic art and lightworks. These were movements that played with the psychology of looking. Did I want to be dazzled? I didn’t know.

My fears, it turns out, were unfounded. The exhibition’s first space focuses on the 1960s, an era shaped by the Cold War, the height of the civil rights movement and the dawn of space travel. To write of hope in relation to that cultural moment feels like surrendering to cliché. Yet the works in this space feel buoyant. They pulse and vibrate and hum. They reach for the viewer.

Next to Static 3 is Schwebend Schweben (Suspended suspension) (1971) by Günther Uecker. The German sculptor made the work by carefully hammering nails onto white canvas. Step to the left or the right and the nail field undulates like a meadow. In the process, the violence of the material is neutered, rendered tactile.

Atmosphère chromoplastique (Chromoplastic atmosphere) no. 154 (1966) commands the first wall. It’s a work by Luis Tomasello, an Argentine artist of Italian descent who relocated to Paris in the 1950s and laid bricks to support himself at art school. Here, he alchemises a stark geometry—sixteen rows of miniature cubes affixed to a square canvas—into an interplay of light and shadow by painting their sides blue and red.

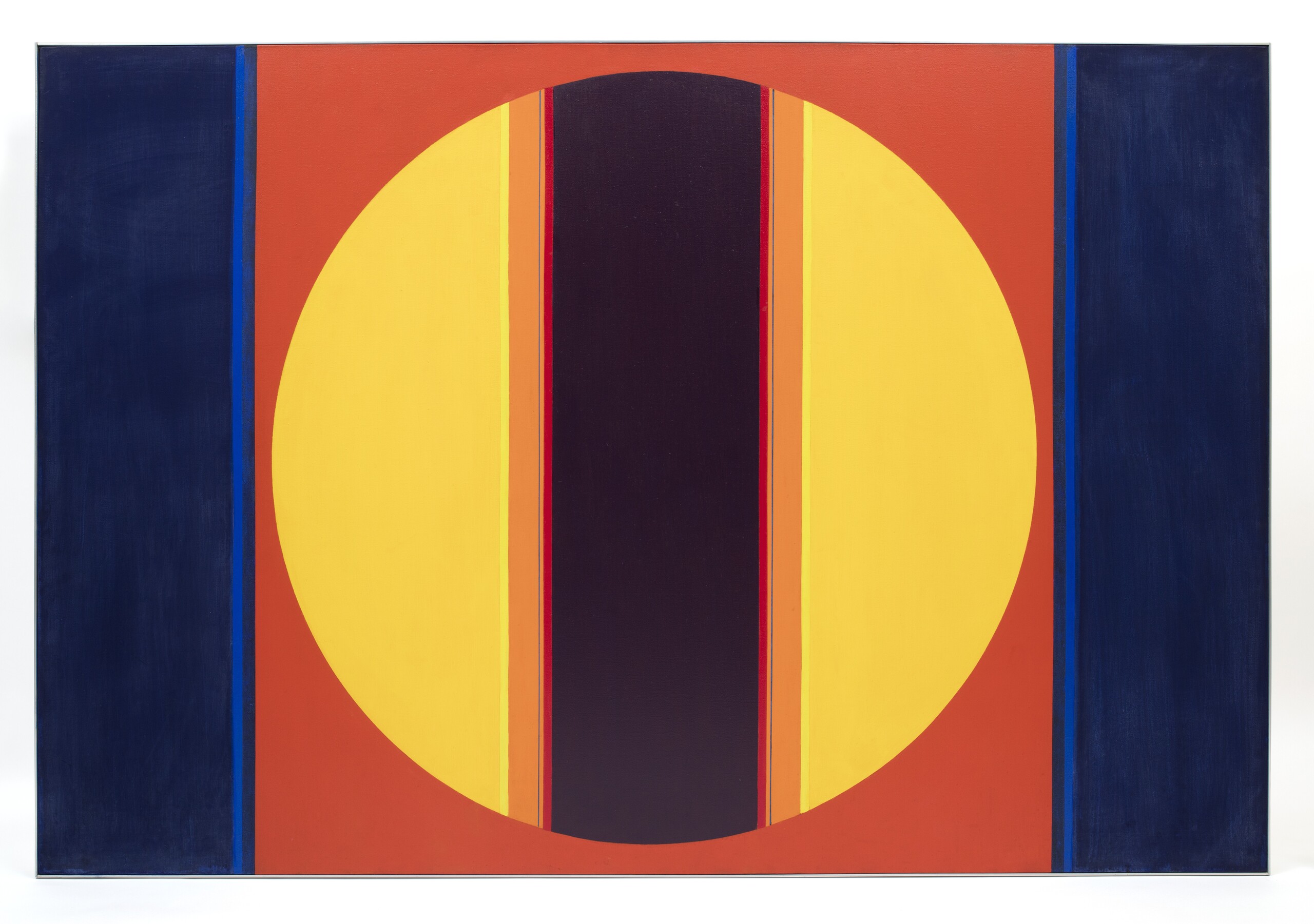

Nearby, I’m drawn to Blue Reflex (1966–67) by Australian artist Ian Burn, a minimalist swathe of indigo rendered in automotive lacquer. Burn, who was born in Geelong but was at the time living in London, is a surprising inclusion, given his close association with conceptual art rather than the op and kinetic art favoured by this part of the show. But Blue Reflex feels interested in how the refractive sheen of a surface could double as a portal to the spiritual. The work, artificial as it is, recalls the blue of the horizon—a colour that resembles form, seems to exist in three dimensions. Opposite sits the gorgeous Two horizons (1966) by Polish émigré Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski, one of the country’s first multimedia artists. He uses lines and orbs on searing orange, adhesive tape on enamel paint, to evoke radiant Central Australian light.

To spend time with these works isn’t to bask in optical illusions. It’s to be reminded, however fleetingly, that our perception shapes our reality. That if what we see challenges what we expect to see, then our experience of ourselves—and of the world—can change.

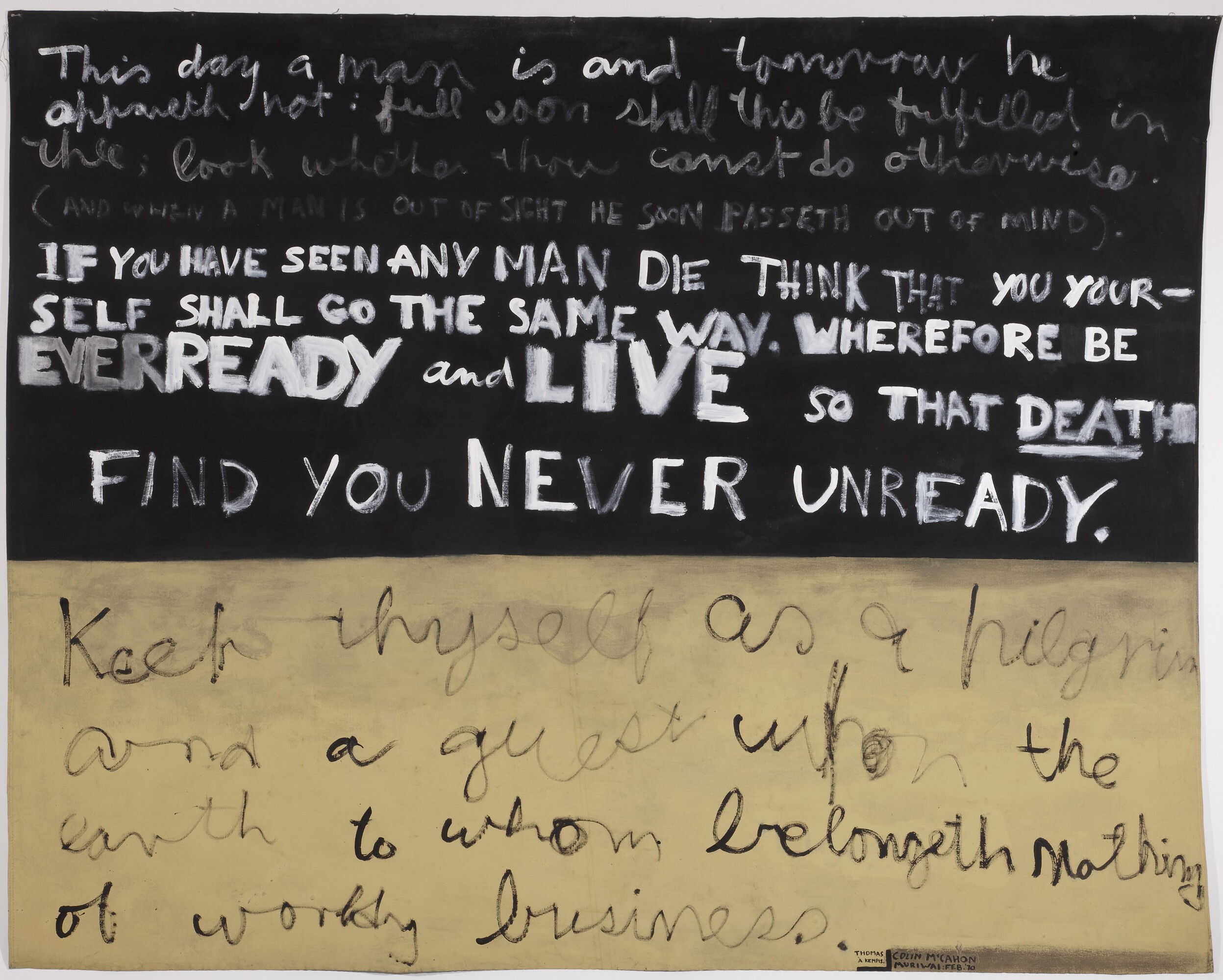

The Power Collection is home to 1500 works featuring international art stars such as Riley, Jasper Johns, Joseph Beuys and On Kawara along with counterparts from Australia and Aotearoa such as Sydney Ball, Colin McCahon, Gordon Walters and Imants Tillers. A January 2022 article in The Sydney Morning Herald reported that, until the construction of the Chau Chak Wing Museum in 2020, the collection had been sitting untouched in an Inner West warehouse for five decades. The press around Light and Darkness describes it as “buried treasure”, while the exhibition positions itself as a “time capsule”. That art from the past could be a gift to the present, of course, has new art-world currency since the revival, fuelled by feminist art historians, of overlooked figures like Hilma af Klint and Agnes Martin.

I take in And Dawn (1971) by Susan Weil, a triptych of painted, crumpled paper that recalls the first blush of pink swallowing the night sky in the morning. I return, a few times, to Saturday (1987) on the other side of the room, a pair of polaroids that merge into each other, perimeters blurred as if animated by a single source of kinetic energy by—who else?—Maria Abramovic and Ulay. And I find it hard to be cynical. The works in Light and Darkness were all acquired no more than five years after their making. They are a response to a period shaped by division and instability. Yet they give off an aura of freshness, of discovery. The best works in the show—-I’m charmed by fingerprints on the Weil—look outward. They throw into stark relief the fractiousness of our equally volatile moment, our desire to cling to our truths, to stay in our private bubbles of experience.

The idea of the time capsule, an artefact from a distant era, can also inoculate against criticism. According to the show’s catalogue, curators Gordon Thomson and Bernard Smith originally imagined the Power Collection as Western European.

The collection was assembled during a time marked by cultural cringe. Before the 1967 Referendum that counted Indigenous people in the Constitution, and before the end of the White Australia Policy. The collection’s emphasis on the British, German and Italian avant-garde, to me, speaks to the ways in which European cultural centres were signifiers of both the cosmopolitan and the international in the national imaginary. The silent assumption—one that still persists—is that Australian art and culture was provincial, rather than global. This logic, it goes without saying, excludes non-Western aesthetic traditions—tantric art, Sufism—that were preoccupied with questions of perception and the relationship between seeing and being centuries before the dawn of Western modernism.

Aside from a handful of Japanese artists, there are barely any people of colour in Light and Darkness. Women appear from the mid-70s after Lucy Lippard, the feminist art critic, visited Sydney at the height of second-wave feminism to give the Power Lecture. Indigenous artists—such as George Milpurrurru Malibirr and John Mawurndjul—are only represented in the collection after the 1984 appointment of Djon Mundine, who acquired 257 bark paintings and wood-carved objects from northeast Arnhem Land.

The show is framed by chronology. Artworks are arranged by decade. On the show’s final, standout wall, a timeline contextualises the story of the collection against the backdrop of social history: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Bicentennial of colonial invasion, Whitlam’s election. But, at times, this emphasis on Western teleology also hints at a false narrative of progress. It’s one that frames the story of art and artists as linear rather than cyclical. An onward march of movements and ideas that suggests a directly proportional relationship between social revolution and visual breakthroughs. This risks eliding the ways in which art history is a construct: made, written, subject to ideology. It overlooks the fact that a national collection is a powerful arbiter of cultural value. And the way its gaps and silences reverberate in the here and now.

There are works in Light and Darkness that are transcendent. Robert Rauschenberg’s Sand (Hoarfrost editions) (1984), a fluttering silk panel bearing a photomontage cribbed from the Los Angeles Times. An orange-and-silver mobile from Julio Le Parc, part of Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel or GRAV, a collective of Paris kinetic artists whose shared output is one of the show’s many pleasures. I can’t stop thinking about Sawdy (1971) by Edward Kienholz, a Datsun car door mounted on the wall of the darkened central gallery. Is it a readymade? A multiple? I look through the window and there’s a scene: six white policemen around a Black man in a parking lot, a prelude to racist crime. The best works in Light and Darkness show us how we see. How—with a trick of perspective, the illusion of motion—our vision is fallible. This work makes clear that if perception is a story we tell ourselves, we are accountable to what we’re looking at—and to what, exactly, we decide to look past.

Neha Kale is a writer and critic who lives and works on unceded Gadigal land. Her writing on art, contemporary culture and society appears widely in Australian and international publications. She was formerly editor and editor-at-large of VAULT magazine.