Installation view of Tony Clark and Joanne Ritson, Jasperware Arrangement, 2024, plaster, aluminium, cotton, and hessian, 52 x 130 x 30 cm, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

Tony Clark: Unsculpted

Ebony Maurice-Wilmott

Invented by Josiah Wedgewood in the 1770s, Jasperware is defined by the cream porcelain relief embellishments that push out from Wedgewood blue pottery pieces. Arguably the Western world’s most identifiable example of Classical relief sculpture assimilated into mass production, Jasperware’s simple form and domestic ubiquity almost disqualifies it as sculpture. It’s also a core motif of Tony Clark’s paintings; obsessed, as they are, with being things that refer to but are not sculpture. Unsculpted, at Buxton Contemporary, spans forty years of Tony Clark’s career, with a focus on his use of “sculpture as a stick to beat painting with”.

Tony Clark is a nomadic artist with studios located in Sicily, Essen, Germany and far North Queensland. His work/life arrangement is as restless as his engagement with style. The exhibition sets the tone of Clark as the seventy-one year-old enfant terrible of Classicism. His sculptural paintings and ongoing collaborative projects twist the clashing Greek and Roman principles of style associated with harmony, restraint, and adherence into layered pastiches which transgress neatly into postmodernism. He introduces a conversation, albeit one that started centuries ago, between painting and sculpture, their ability to parody one another, whilst illuminating the slippages and mistranslations that occur along the way.

Installation view of Tony Clark and Joanne Ritson, Jasperware Arrangement, 2024, plaster, aluminium, cotton, and hessian, 52 x 130 x 30 cm, and Tony Clark, Jasperware (Landscape), 1993, acrylic on canvas, 244 x 549 cm, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. © Michael Buxton Collection, the University of Melbourne Art Collection. Photo: Christian Capurro.

The exhibition opens with Clark’s Jasperware (Landscape) (1993), an acrylic on canvas triptych that presents a clustered bas-relief form. The lumpy shape refers to Andrea Mantegna’s The introduction of the cult of Cybele in Rome (1505-06), in which Mantegna imitates a sculptural stone frieze in paint. Clark distills Mantegna’s shadowing strategy into a formula of two neutral greys, to outline cream forms on a flat pale blue. Clark eschews Jasperware’s more recognisable referential markers, such as cherubs and men and women in togas, in favour of a cartoonish conglomerate of palm trees. One of these palms is closed like an umbrella with a surfboard behind it and the other is shaped like a cheerleader’s pom pom ejaculating a cloud which looks like a breast with a bulb attached, all connected to a flying carpet. The hallucinogenic image reveals to us the human tendency to force identity on amorphous shapes, akin to a game of cloud gazing. It’s evident that Clark isn’t concerned with Jasperware’s traditional imagery, but its plasticity.

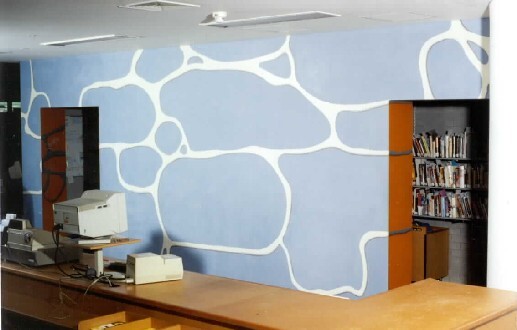

Clark’s Jasperware Mural, painted over thirty years ago in 1994 at the St. Kilda Public Library, stretches this idea to its limit. The mural’s all-over treatment of flat irregular ovals traverses two of the library’s walls like a sinuous web. Engaging the library’s architecture by painting directly onto its surface, Clark’s mural pursues a kind of grandiose abstract classicism, signalling the history of classical frescoes and friezes, which sit in contrast to the optimistic community art that might be commissioned in libraries today. Clark has said: “I like the set-up to have some obstacle or flaw…There has to be some grit in the oyster”. Clark’s mural becomes the grit which agitates the design of Enrico Taglietti’s Brutalist architecture. Full of irregular rounded forms, Clark’s mural offers an oasis-like respite to the hard rectilinear lines which define the rest of the library that encapsulates the notion of “punk classicism” often used to describe his work.

Installation view of Tony Clark, Jasperware Mural, 1994, acrylic and varnish on wall, 210 x 970 x 40 cm, St. Kilda Public Library, © City of Port Philip and Murray White Room, Melbourne. Photo: unknown.

In 2024, Clark collaborated with artist Joanne Ritson on Jasperware Arrangement, a plaster and cotton sculpture which sits on a bed of hessian and aluminium. At Buxton, this work is placed adjacent to the painting, Jasperware Landscape. Guided by sculptural sketches that Clark made decades ago, Ritson was given artistic licence to invent the back of the work, as Clark only drew each form from a frontal perspective. Ritson was able to tease out the Jasperware (Landscape) further using the front-facing nature and silhouette of Clark’s drawings. The palm trees grow propellors and, when viewed from the rear, the bulbous cloud becomes something resembling a crack pipe, continuing the thread of mistranslation from one medium to another, one artist to another, one viewer to the next.

Installation view of Tony Clark and Joanne Ritson, Jasperware Arrangement, 2024, plaster, aluminium, cotton, and hessian, 52 x 130 x 30 cm, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

Ritson tells me she was very fortunate to have Tony Clark and Howard Arkley as her teachers at Prahran College in 1983. It started a long friendship with both. In 1989, Clark and Ritson, as well as (artist/curator) Michael Graf, spent a three-month residency at Arthur Boyd’s farmhouse in Tuscany. Ritson and Clark’s collaboration for Unsculpted is a continuation of ideas formed during that time in Italy, when she was particularly interested in reliquaries, ex votos and the medium of beeswax. Clark also happened to teach the late Rowland S. Howard, one of Melbourne’s post-punk legends, who became a muse for Clark. Clark has made over sixty-five portraits of Howard, one of which hangs at Unsculpted. Design for a Cameo Portrait I (2019) depicts Howard dressed in formal arrangement, doubling as a grandiose death portrait. A lot of Clark’s clout is vampiristically sculpted from Melbourne’s post-punk players, namely Howard and Nick Cave. We are not allowed to forget that Clark did the sleeve art for The Best of Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds (1998) and No More Shall We Part (2001): the original painting for the latter hovers above Howard’s portrait.

Installation view of Tony Clark, Design for a Cameo Portrait I, 2019, acrylic and ink on canvas, 61 x 45.5 cm, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. © The artist and Murray White Room, Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

That being said, Cave and Howard’s anguished music is oddly fitting for Clark’s continued interest in Classical subject matter. In a 1984 interview with Sue Cramer, Clark admitted “Classicism seemed like the language best equipped to carry a kind of resignation, certain melancholic and nostalgic attitudes”. Upstairs at Buxton, Clark’s first public work Technical Manifesto of Town Planning, originally exhibited at John Nixon’s Art Projects in 1982, consists of a photograph and small paintings on canvas board placed on a thin piece of dowel, displaying architecture, functional and non-functional. Like a child playing town-planner, Clark selects architecture imbued with a tragic quality such as a mortuary station, a cemetery, the Albert Memorial, punctuated with the classical ruins of the colosseum, pantheon, and the Cenotaph building. Being Clark’s first public work, his manifesto suggests a promise to treat architecture as a central motif, a promise he has kept.

Detail of Tony Clark, Technical Manifesto of Town Planning, 1982, oil on canvas boards and photograph, dimensions variable, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

Across the room, Clark’s paintings on stretcher bars depict chains of candy-coloured ovoid forms like Brancusian vertical stacks of eggs rendered with the same treatment of flat colour and gradated light to dark shading as the Jasperware paintings. The works from the 1997 series are titled Halasana, Parvatasana, and Dhanurasana, after Yoga positions that stretch the back. Clark makes the connection between the support of a painting to his ambiguous chains which could be interpreted as a human spine, with the eggs doubling as vertebra. Although the strict verticality of the stack blurs the line between body and architectural support, resembling something closer to an architectural column or rounded balustrade. Why is a back a balustrade, or column? Maybe the column is metonymic for Classicism as the ‘backbone’ for all of Clark’s work.

Installation view of Tony Clark, Untitled #9, Dhanurasana, Untitled #3, Halasana, Untitled #6, Parvatasana, 1997, oil on wood, dimensions variable, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. Photo: Christian Capurro.

A lyric drama in four acts by Clark, Der Zweck (1981) is an example of an earlier work which contains architectural themes. Act one of Der Zweck opens with workmen putting the “final touches to the façade of a giant mosque under construction”, with a designer, named Jelladin, consulted in regards to the interior decoration of the structure. Later Jelladin rediscovers Christianity right before the second-coming of Jesus. Clark has referred to Classicism as “the Catholic Church of art and when you’ve been a naughty boy, it’s what you come home to.” Clark’s interest in Classicism as a vessel for nostalgia and melancholy reminds me of Walter Benjamin’s description of the angel of history in Paul Klee’s 1920 painting ‘Angelus Novus’. Benjamin writes: “his face is turned toward the past…the angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.” I imagine Clark here, back turned, invested in ideas which were prominent hundreds of years ago, in a music scene that has since left St. Kilda, unwilling to turn around and face the future.

Installation view of Tony Clark, Architectural motif with Putti I and II, 2023, acrylic and permanent marker ink on paper, 99.5 x 74.5 cm, Buxton Contemporary, the University of Melbourne. © the artist and Murray White Room. Photo: Christian Capurro.

The artist Rose Nolan, who used to be a librarian at the St. Kilda Public Library, once said that she met Nick Cave when he came to visit the Jasperware Mural. Nolan would periodically get Tony in to check the condition of the mural, unofficially, as it was positioned outside the staff room and would get scuffed by book carts. While Nolan expressed concern for the future of the piece, Clark was relaxed: “I live in the ruins of Syracuse”, he would reason. During my own visit, a librarian told me excitedly that someone had punched a hole in it once (at least they got around to fixing that). Clark’s nonchalance towards the slow degradation of his mural reveals his comfort with the art form’s ephemeral nature. His forecast of ruin has now been confirmed—I’ve been informed that the work had been deaccessioned from the council’s collection and that plans were in place to remove the work entirely. So, to get the full Clark experience, one that captures both his sculpturally informed painting practice and his tragic ruins, I recommend seeing Unsculpted at Buxton, then catching the number sixteen tram to the library to see the mural, before it’s too late.

Installation view of Tony Clark, Jasperware Landscape, 1994, acrylic and varnish on wall, 210 x 970 x 40 cm, St. Kilda Public Library, Melbourne. Photo: Ebony Maurice-Wilmott.

Ebony Maurice-Wilmott is an artist from Naarm/Melbourne