Justine Varga, Tachisme

Chelsea Hopper

The only way to access the exhibition is online. You type in your email address and are automatically added to the Tolarno Galleries’ mailing list along with a promise that the gallery “will not share your details with anyone else”. Underneath, a digital countdown is ticking away the days, hours, minutes and seconds left until the “viewing space” closes. Is anyone really keeping track of time at the moment? Perhaps it’s a bid to foster some sense of anticipation. The strategy worked wonders in the past. Famously, when Psycho (1960) was first screened at cinemas, Hitchcock required theatres to run a countdown in the foyer that periodically indicated the impending start of the film screening. Here, the sense of anticipation falls flat. The expectation of clicking and scrolling through an online exhibition doesn’t exactly scream exciting; but at least we get to see the work.

Once “logged in”, scrolling through the exhibition reveals a menagerie of text interspersed with images and bookended with YouTube links. In the first sentence we are introduced to Justine Varga as someone “known for her luminous photographs, some made with a camera and some without (and some made with a combination of the two)”. Above the text sits a press shot of Varga standing arms crossed in front of Photogenic Drawing (2018)—a photographic negative which earned her last year’s Dobell Drawing Prize. Below the text, brief and impressive lines list the awards Varga has received since 2013, notably the Olive Cotton Award for Photographic Portraiture in 2017, alongside a number of state collections that have acquired her work. This fodder, typically saved for a laminated file left on the front desk of a gallery, somehow is a focal point of the experience of this exhibition. The pages are now lifted out of their laminated sheets, transposed, exported and thinly spread onto the browser’s “viewing space”, nestled between the five new chromogenic prints part of Varga’s Tachisme series on the webpage.

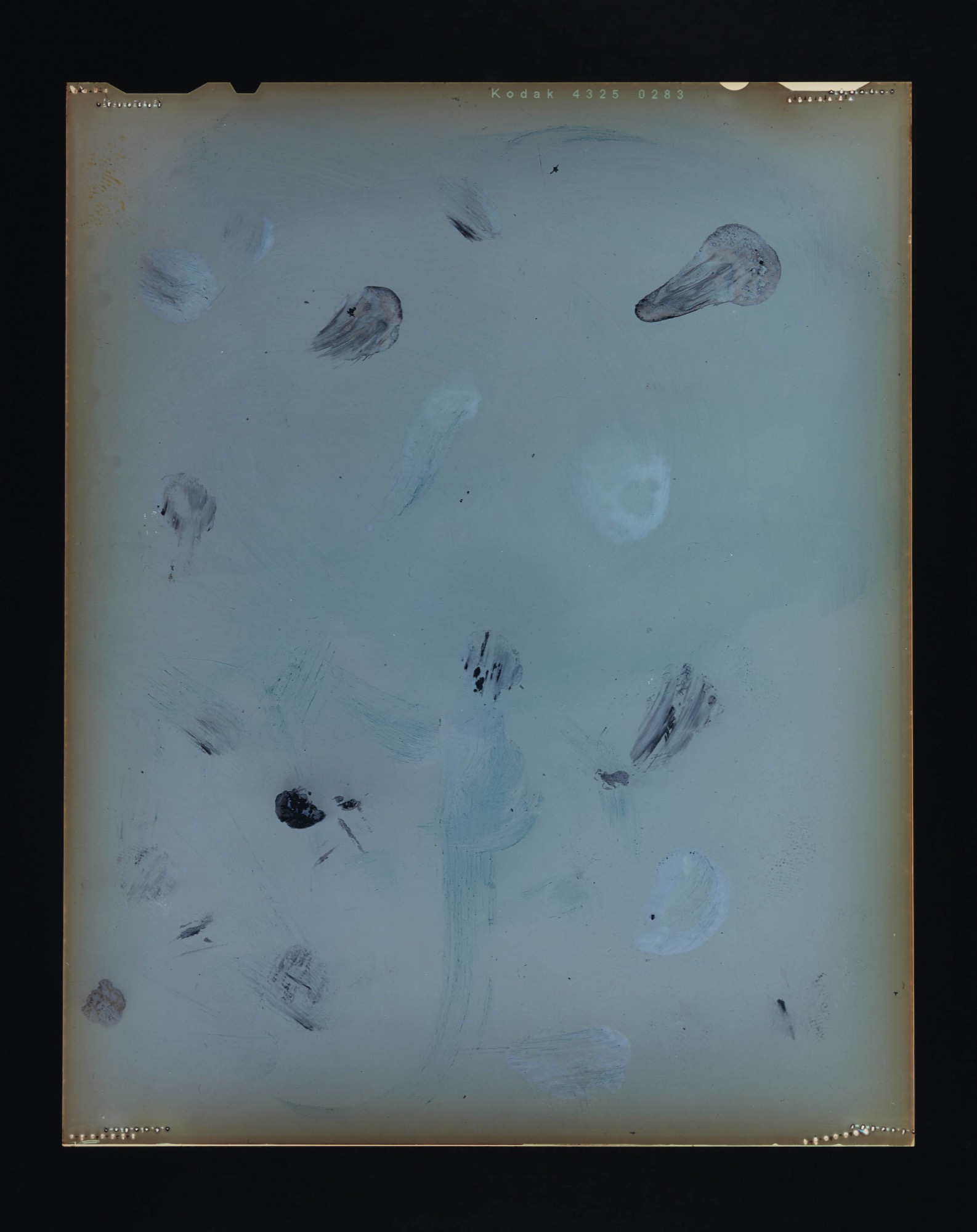

“Tachism” of course refers to the French version of American “Abstract Expressionism”, a type of abstract painting that became popular in the late 1940s/50s and is characterised by the use of irregular dabs, splotches or stains of colour. Notably, Tachism was distinguished by spontaneous, gestural expressions that seemed sensual and suave, unlike the work of Abstract Expressionists, which were aggressive in comparison. What does it mean to talk about image-making in terms of how it is positioned on the spectrum that sits between photography and painting? In Refraction (2018–19) we find quickly painted horizontal brush strokes of black and blue pigment appearing like watercolours on a slab of sepia toned glass. Refraction, and arguably the other four prints in the series, look like they contain painted elements, and Varga’s gestural movements also point to the title of the series. The word tache is French for “spot” or “blotch”, so to a degree Varga’s titling of the series seems appropriate. But why does she recuperate such a narrative? By aligning the series with a European painting movement Varga, unconsciously or not, reflects an ideology within the economy of the work.

Numerous versions of the works are displayed. Test strips are shown taped to a creamy wall; final prints freshly framed along with copies of hi-res jpegs. An image of three prints, Visage (2018–19), handsomely pinned up in a row, is telling of their size and scale that is ultimately lost in the floating dimension of the viewing space. The repetitive trial and error evident in another image is a document of process on the way to the final version of Aggregate (2018–19), pinned to the fore behind large rectangular scraps of failed sepia and tonally washed out test prints.

Some parts of the exhibition are not accessible. In a short video near the top of the webpage, Varga—who currently resides in Oxford—speaks of a large installation piece that was to be on view to the public as part of the exhibition (it was inevitably postponed) which would have required “my presence and the creative process that will reoccur in the gallery space”. Varga places great value on the physical and material experience of the work. To an extent, I am able to receive it. Previously, when experiencing Varga’s photographs in the flesh (even bearing witness to an enormous unframed print unravelled for viewing as an acquisition), they had an immense capacity to draw out an emotional response. However, the web experience draws out something in Varga that’s always already uncomfortable: its effectiveness at diverting our attention to the work’s aestheticisation, the relationship to its commodification.

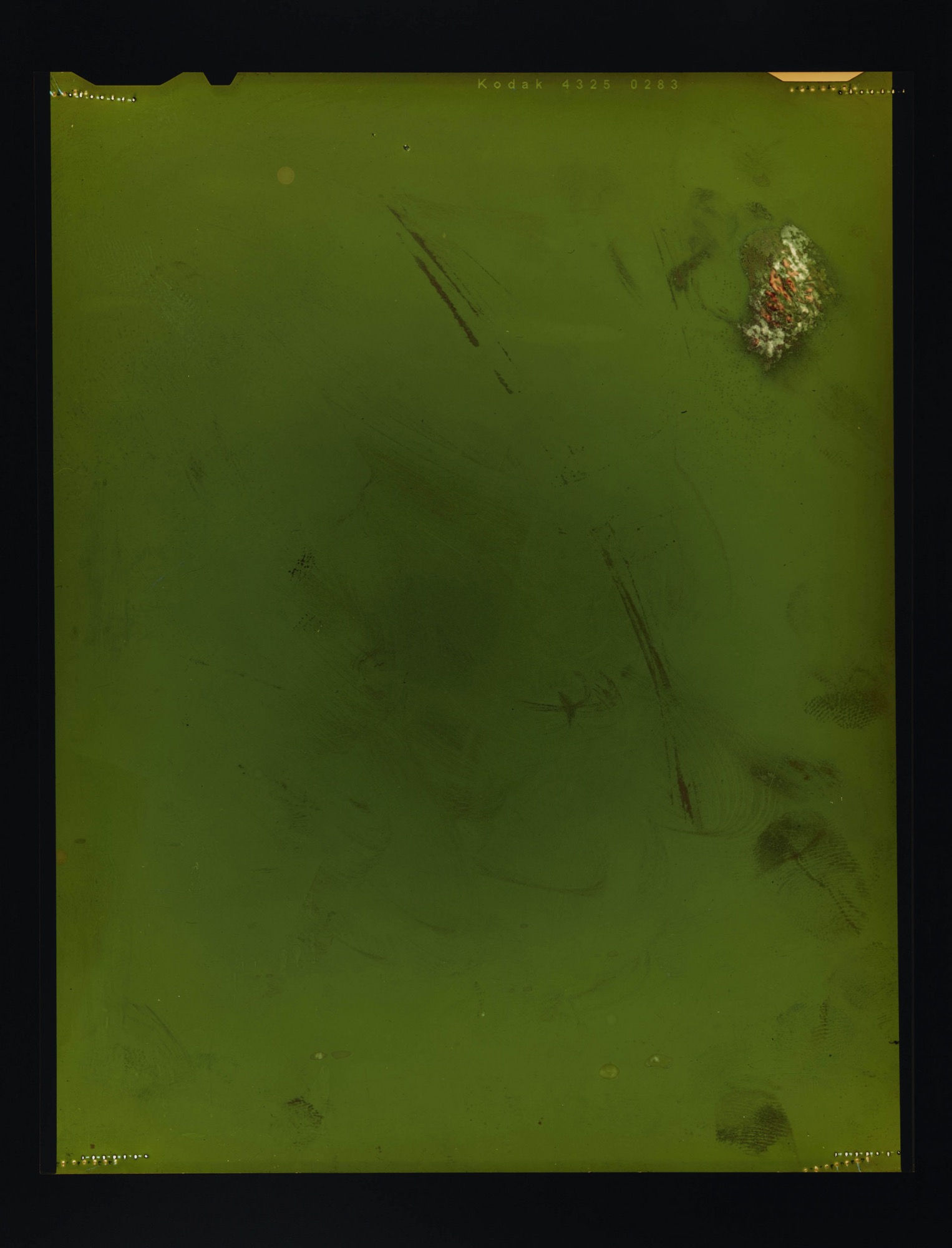

Varga’s physical presence is deeply intrinsic to the production of the work too. All five chromogenic prints of the Tachisme series are an index of Varga’s bodily experience with the negatives she touches. Either she’s scratching the surface, creating blemishes, pressing or rubbing fingerprints; I’d also like to think, given Varga has used spit and saliva in the past, there is licking involved, as parts of Aggregate (2018–19) appear to resemble marks from a wet tongue. Her hand movements create a fantastic smudge in the centre of Visage (2018–19). It is so visually enticing amongst the polarising thick toxic green of the print. My enthusiasm is partially attributed to the one perk of viewing the exhibition online: I have a certain agency to enlarge the hi-res jpegs, traverse the pixels and scan in detail the visible mark-making usually kept at a distance behind the frames of these large prints and the protocols of a gallery viewing.

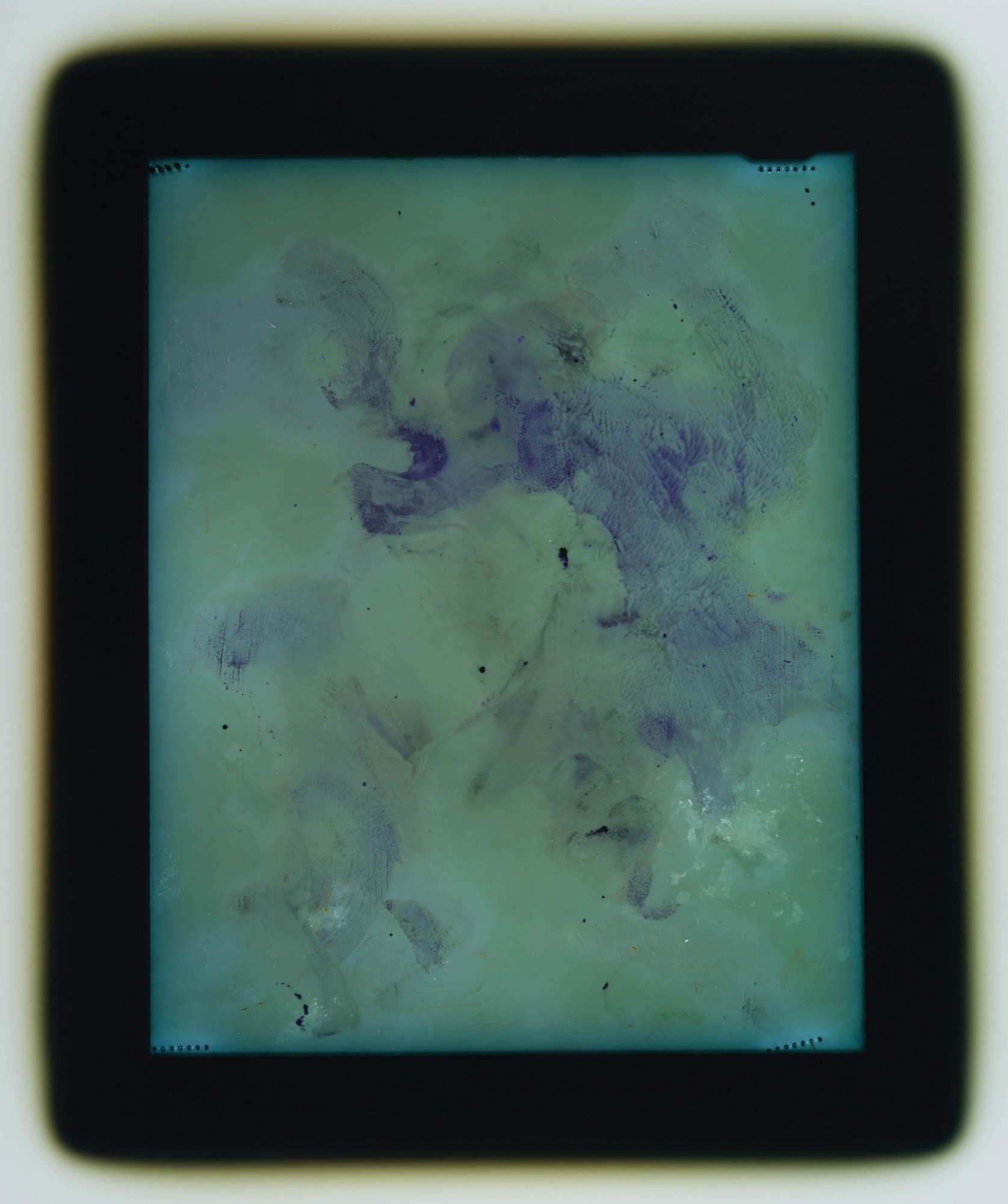

Both Influence (2018–19) and Contusion (2018–19) include in their exposures an unmasked enlarger frame, notable for its unfocused soft rounded edges and projected light—on my computer screen, they appear like glowing iPads. As with this reframing—its inclusion of the mechanics in which each of these negatives sits and undergoes such extreme transformations—here Varga intentionally diminishes the impressions of negatives for view. Both radiating colours of purples, deep sea-green, teal and scratches of yellowish amber peep through, too. Once again, I get caught up in the aesthetic racket.

Beside the jpegs, editions of the prints and their prices are flanked in the margins. You cannot un-see this—Visage (2018–19) is shown to be the most successful work commercially speaking, while Influence (2018–19) or Aggregate (2018–19) have yet to hit the radar of potential buyers. I can only hedge my bets as to why these two prints haven’t sold as well as others. On my screen its harder to see clearly Varga’s intense mark making with the additional framing, which, in another image that appears when scrolling further down the webpage, shows the exact same image this time within a physical frame, as if the image is transformed into a print, a real object meant for purchase.

Everything about Varga’s image-making is photographic. The way she engages with photography’s attributes: the index, enlargement processes, treatment of negatives, using light sensitive chemicals, the list goes on. Although an early career artist, Varga’s works are consistently referenced by curators who relate her image-making to photography’s etymology (light) and how photography has the innate ability to retain the “trace” of its subject. In Varga’s case, for example, Maternal Line (2017) thematises this trace as a portrait produced without camera or caption but marked with pen and saliva on a piece of film by her maternal grandmother. She is acutely aware of the history of photography and it is easy to spot. The titles are a dead giveaway—Varga’s award winning work, Photogenic Drawing (2018) references William Henry Fox Talbot, the English scientist who perfected the optical and chemical aspects of photography. Although the titles of works from the Tachisme series aren’t as explicit, they subtly conjure up references to photography: “Visage”, the manifestation, image or aspect of something; or “Aggregate”, a whole formed by combining several separate elements.

At a time when Varga is consistently producing work where her artistic intentions seek to stake out a space for an authentic, emotionally embodied experience, it is a battle when viewing her works online. Ultimately, what the online exhibition space undoes through its layout and add-ons is allow a witnessing of the transaction of commercial art much more explicitly than in person where knowing (and seeing) the prices falls away or is left unseen. As such, the audience who experiences the work is tailored to the collector—someone on the mailing list I’ve just been forced to join to view the work. Perfect visual capitalism disguised as rugged individualism.

You can view Varga’s online exhibition here.

Chelsea is a curator and writer based in Melbourne.