Jenny Watson: The Fabric of Fantasy

Chelsea Hopper

When you first start making stuff, finding your voice as an artist can be a bit of a slog. There will always be bad paintings, clumsy drawings of still lifes and failed charcoal figures from the life drawing classes you were forced to take at art school. It can be a case of trying things out and then trying them again and again. After a few years, you ultimately make the decision as to whether you want to stick with it for the rest of your life, or just stop and do something else.

The Fabric of Fantasy shows that Jenny Watson found her voice. It is an occasion to witness an artist's conceptual painting practice that has evolved over a four-decade period. The survey exhibition (curated by Anna Davis and travelling from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney) contains over 70 works dispersed amongst six rooms of Heide III, from early realist paintings, drawings, objects and animation to a number of key series of works on fabric. The central gallery is covered in a plush pink pattern where several large works are hung intermittently across the walls. And as you drift further into the show, you are caught hearing punk music blaring out of a room: a curatorial attempt to create a 'vibe'.

But apart from one room, what becomes apparent when walking through the exhibition is that most of the works on display look as if they were produced over a much shorter period, as though Watson were fresh out of art school. Watson's self-defined style—consciously 'naïve'—allows her a certain capacity to endlessly revisit a handful of motifs throughout her many works.

Horses, for example, are Watson's staple, stemming out of a childhood in the Dandenong Ranges. It's as if she entered the horse-mad teenage girl phase and just never grew out of it. She has of course painted many horses: greys, bay and chestnuts, typically without background detail. But her interest in horses also extends beyond paint to experimenting with the material support for her paintings. In Watson's case this is hessian, typically used for hay and feed bags, which are repurposed as canvas; 6pm, 1992, is a prime example of this. Even horse tails appear draped over figures. This Year's Fashion I, 1984, for example, reveals itself as a kind of double self-portrait. This sensibility is also echoed in He'll be my Mirror 2013, which depicts a woman with long orange hair staring back at her reflection in a horse's belly, alluding to the creature as a kind of mirroring process.

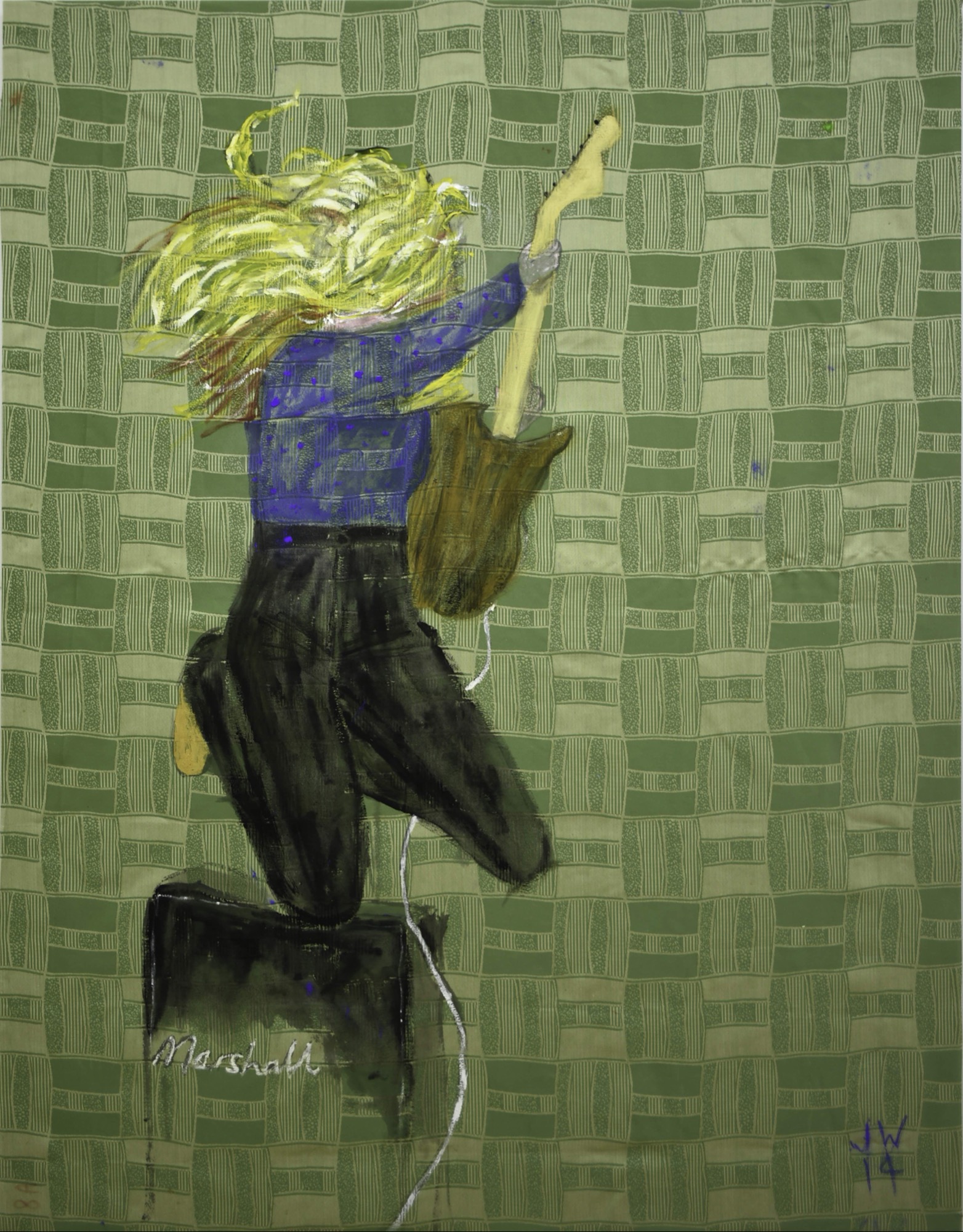

Further along in the exhibition, Watson trades in horses for underground music. In her early 20s, music attained renewed importance for Watson when, as she reminisces in a catalogue interview, she was given a copy of Patti Smith's breakaway album, released in 1975, which was funnily enough titled 'Horses'. It was Smith's maverick brand of underground music that became a key influence on the intersection of music and art in Watson's practice.

No doubt the punk subculture back in Melbourne had an impact too. Watson regularly saw early performances from bands like The Boys Next Door, admired their stage presence and drew their portraits as a tribute to the scene. Here again, then, another art school trope of painting your 'favourite' musicians emerge as a defining aspect of Watson's practice. We see, for example, a drawing of artist-cum-musician Nick Cave, who was also a student of Watson's before quitting art school (thus becoming one of the many artists fated to 'just do something else').

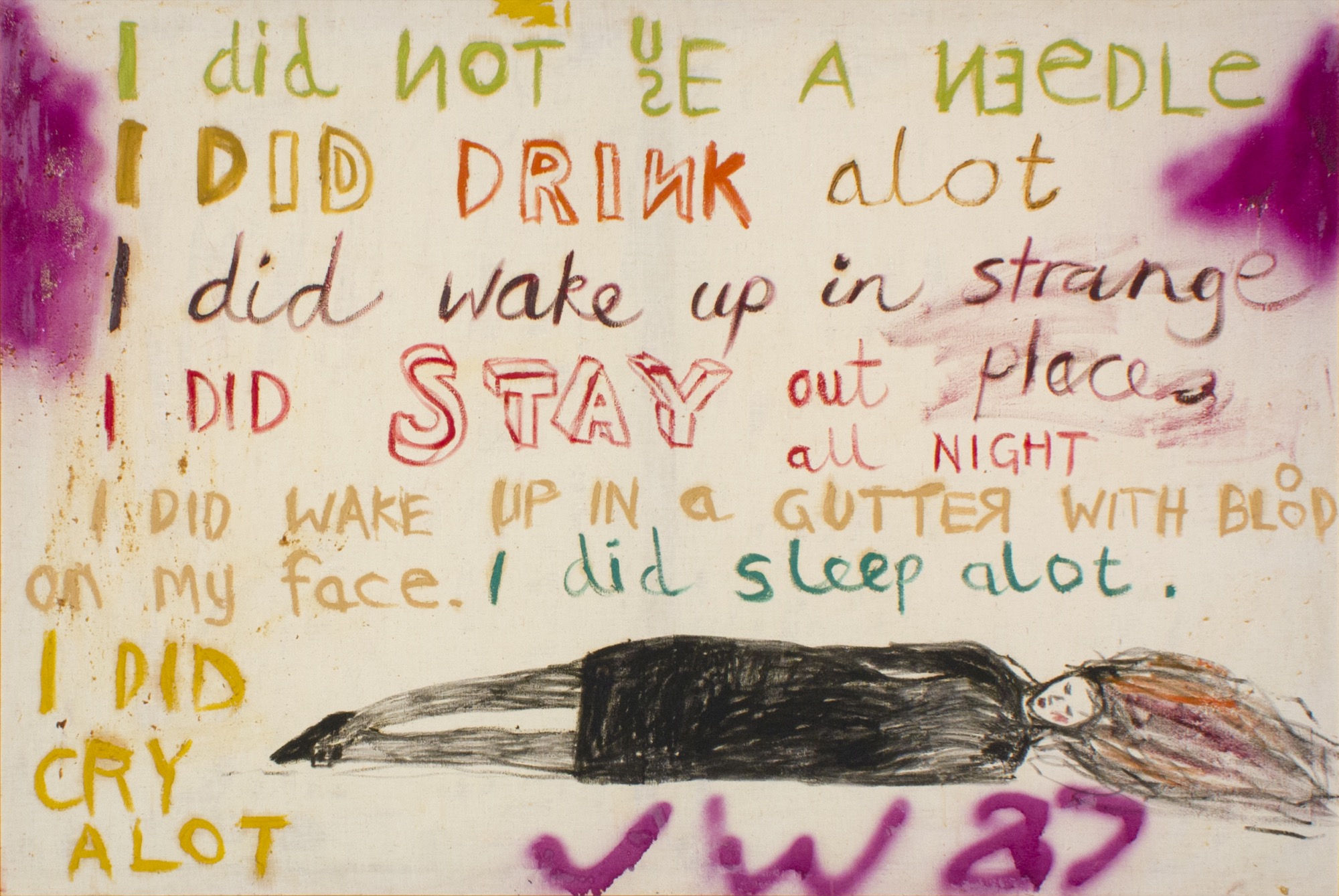

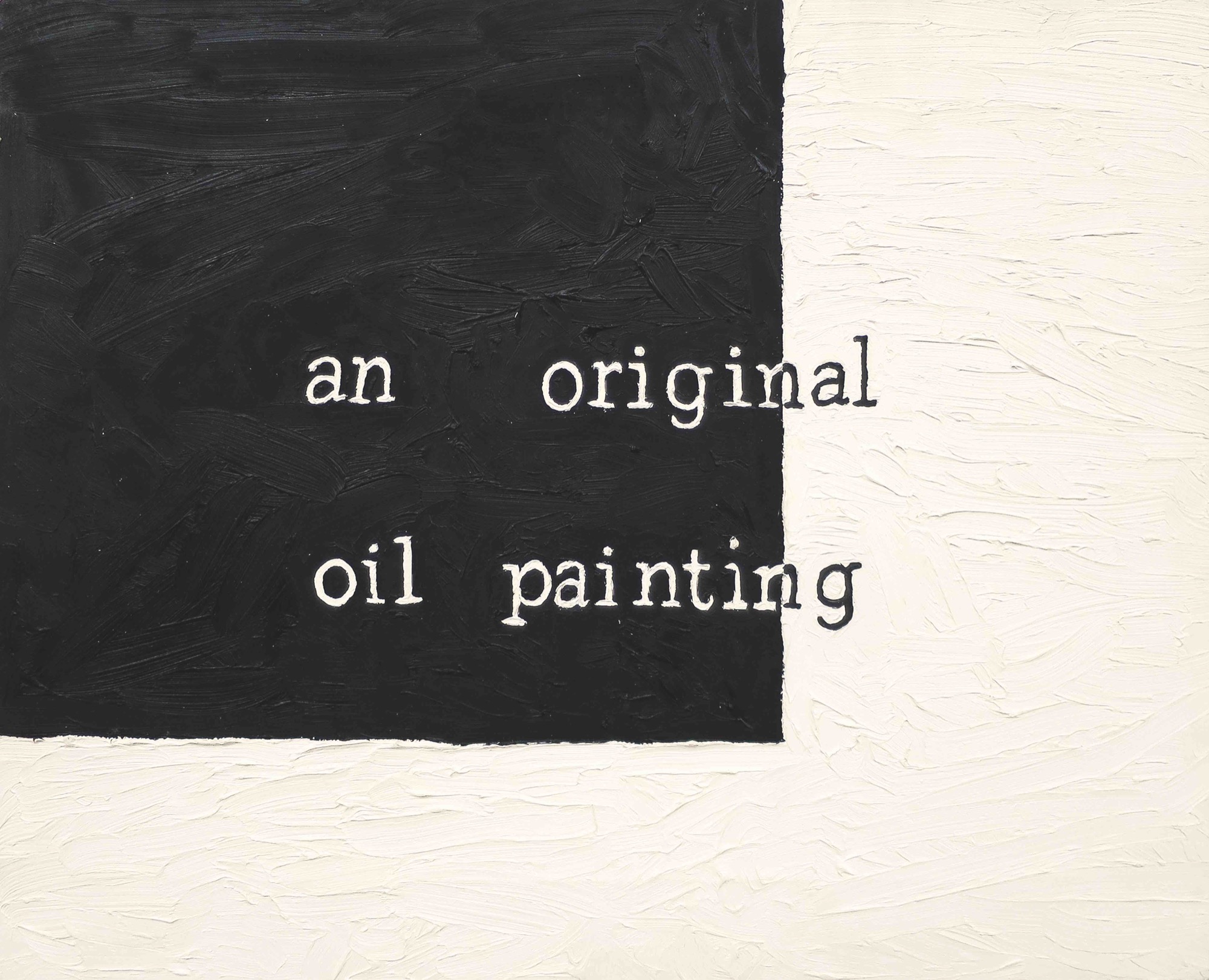

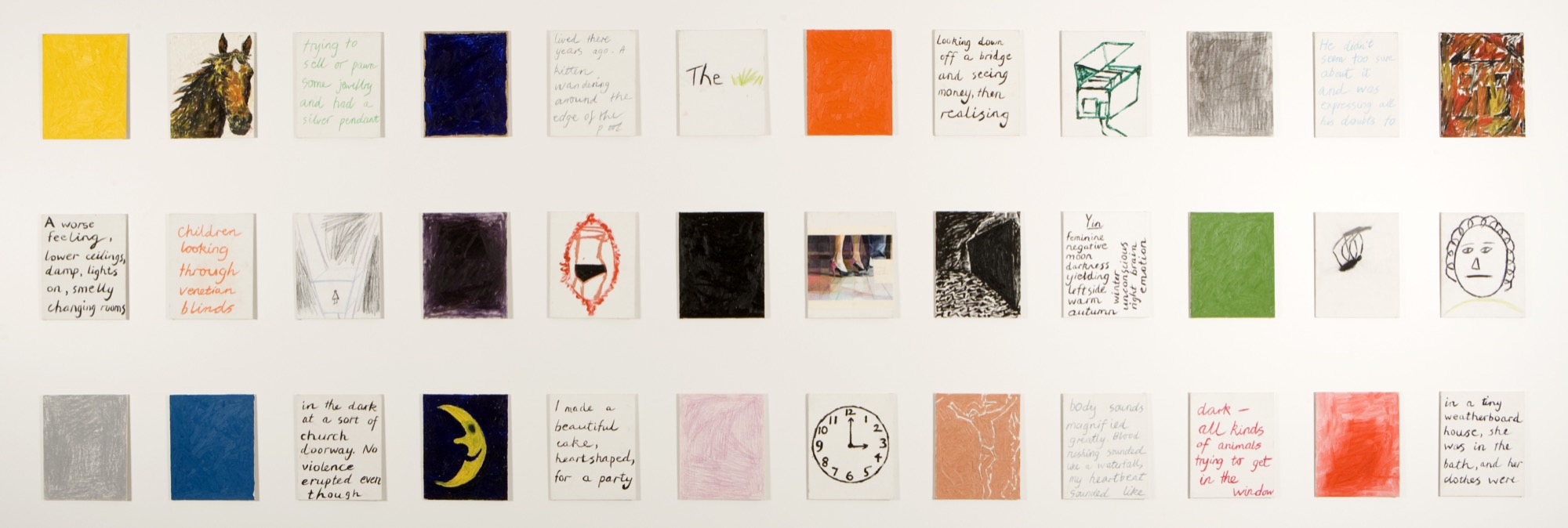

There's only one of two early conceptual text paintings on display, Watson made in a short-lived period during the late 70's. This is a testament to Watson's ability to dip in and out of contemporary styles, latching onto what she likes and letting go of the rest. Like an art school student, she 'tries on' minimalism and conceptualism—the two competing movements of the 60s and 70s—but then quickly moves on down her own path. The use of language in the text paintings of Ed Ruscha and John Baldessari inspired Watson at art school, but once she realised she could paint text about anything, she makes it autobiographical, delving into her subconscious dreams, wishes and desires. The relationship between text and image became central to her work, which frequently includes a small panel of hand-painted text that sits alongside a larger image, undercutting or changing its meaning. Mini-ecology 1981, Ballerina 1992, Dolly Mop 2007, Change 2001, I've got a Dirty Pig on my Mind 2013, are exemplary of this technique. It is one way of taking an artwork into a different place, giving the viewer the opportunity to draw their own conclusions from the disparate pairings Watson offers.

The Fabric of Fantasy also demonstrates Watson to be an artist defiant in her approach to art making. A feminism, for example, is evident in her ongoing questioning of what a painting surface might be. For the past 19 years Watson has opted to work primarily with women's clothing as her canvas. The dimensions are made from standard dress fabric widths, and the length cut to be roughly the height of Watson herself. The scale gives these works, which have been hung deceptively higher in the gallery, a human equivalence, which connects the painting to its reality. This combination of human scale and unyielding fabrics gives some of Watson's works a demanding and intensely physical quality.

Where works in The Fabric of Fantasy are not framed and left unstretched, the textiles almost have a life of their own as gravity and Heide's expensive air conditioning blows them around in slight, contained movements. Coupled with her material sensibilities, Watson's feminism is sucked up into the fabrics, emanating out from within the frames of the floating figures she depicts in domestic poses. The blaring red velvet background paired with the text handwriting OBJECTIFICATION in Objectification 1990-91, for example, blatantly raises the question of sexual objectification.

Another quality evident in The Fabric of Fantasy is Watson's deliberate de-skilling of her painterly style. We see the first iterations of this in Dream Palette 1981, based on her dream journal sitting between earlier realistic representations of animals, figures and depictions of childhood homes Watson once resided in amongst the leafy Melbourne suburbs. But perhaps the ultimate achievement of an intimate expression of herself is in Mu-me 1981, based on a memory of a drawing Watson completed in first grade of her mother. It is one of the most spontaneous and least refined works in the exhibition, as if it were done in one go, a remnant of a one-take, one-minute, performance. Pinned loosely to the gallery wall, the large grey Vilene (a fabric commonly used by tailors to line clothes) provides unexpected insight into the deeper spaces of Watson's personal memory.

As a whole, The Fabric of Fantasy shows that Watson has had no trouble finding her voice as an artist. Despite the curator’s attempt to thematise Watson’s work and imbue the exhibition with a punk vibe, for me, the strongest impression of The Fabric of Fantasy is that Watson does what she wants. As she says, 'I have always, and always will, make all the decisions.'

Chelsea Hopper is a curator and writer based in Melbourne.

Title image: Jenny Watson, White Horse with Telescope, 2012, synthetic polymer paint on rabbit skin glue primed cotton, Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery © the artist)