Isadora Vaughan: Rumours of True Things

Ella Howells

Upon entering through Station’s weighty bronze door, Rumours of True Things begins with a whispered welcoming gesture. Isadora Vaughan presents a petite sprig of three local flowers (likely from the Proteaceae family) in a powdery matte finish. Their central node is anchored in place by a soldered loop of jeweller’s wire implanted into the gallery wall like a dermal piercing. Scanning around, the architectural features complement a series of thoughtfully arranged sculptural vignettes. The polished concrete floors provide a neutral backdrop, allowing a restrained pastel palette of lilac, olive, blue and blush to advance. Lofty ceilings with gabled beams contribute to an agricultural omniscience that’s characteristic of Vaughan’s works. This marks Vaughan’s fourth solo offering with Station, revisiting her practice’s alchemical relationality by vacillating between craft, found and recycled objects, horticulture and VCA-trained grottiness. It’s a combination that works for her, especially here. The grot has been washed away, nail beds scrubbed clean, arms stretched wide. We’ve stepped into a new biome.

An assemblage called Less than one percent of original grasslands remain (2023) sees hollyhocks and themeda triandra (red oat grass) dried into straw stalks, their roots embedded into the circular base of an industrial-grade metal dolly trolley. This movable central axis radiates a sense of imminent displacement and erasure that ripples throughout the exhibit. Notably, there is no fixed focal point. Occasionally conjoined with wax, the dead stalks are a reminder of the fateful forced cohabitation they once endured. My mum, who started out as a florist in the 90s, shudders to think of the kilometres of raffia and straw that bound the destinies of her arrangements. They also remind me of the ubiquitous dried pampas grass that posed many a fire hazard during the lockdown years, when interior design girlies turned to Etsy for the right-sized ones to arrange in vintage Facebook Marketplace Chic vases—a cautionary note, do not pair with a lit Diptyque.

The temporal rush of floristry can be felt roaming around the room—farming, planting, growing, reaping, hydrating, transporting, refrigerating, receiving, and arranging flowers—all efforts to preserve their prime before they shrivel. It’s a considerable investment for a fleeting end. Flowers die, occasions pass. Artificial versions crafted from fabric and plastic don’t quite hit the same. Yet here in Vaughan’s Third hand series of works, she immortalises floral forms with the balanced minimalism of ikebana and the sensitivity of a postcolonial botanist (re)presenting an archive. These sculptures are carefully orchestrated arrangements, counterweighted to draw attention to the intricate details of each flowerhead. They delicately flutter on dissected plinths reclaimed and repurposed from the recent Barbara Hepworth show at Heide, as if commemorating the occasion of their upcycled afterlife—an Interflora order for beyond the grave. Flowers for Every Occasion!

Several of the plinths, due to their past lives, have sustained scars—scuffs, cracks, chips—and glimpses into their cavernous insides, where small ceramics loiter as rewards for children’s curious eyes. This violence is an essential counterpoint to the fragile works, preventing them from succumbing to a polished, sterile fate. Notches on the plinths evidence the woodworking craftsmanship of their curvilinear construction, with each line demarcating the passing of seconds on a clock, or a cog that makes an achy wheel turn. Runic sketches by carpenters appear here and there, as forecasts for an event the calendar has surpassed. These are part of a network of clues. The longer I look, the more there is to glean. I jump between each offshoot of this pleasantly schizoid mind-map, letting it hatch into a cyclic synecdoche of nature and artifice. A wiry-looking contraption titled Third hand: Austrostipa Elegantissima alludes to an electrode brain stimulation helmet, compelling me to focus on the journey, not the destination.

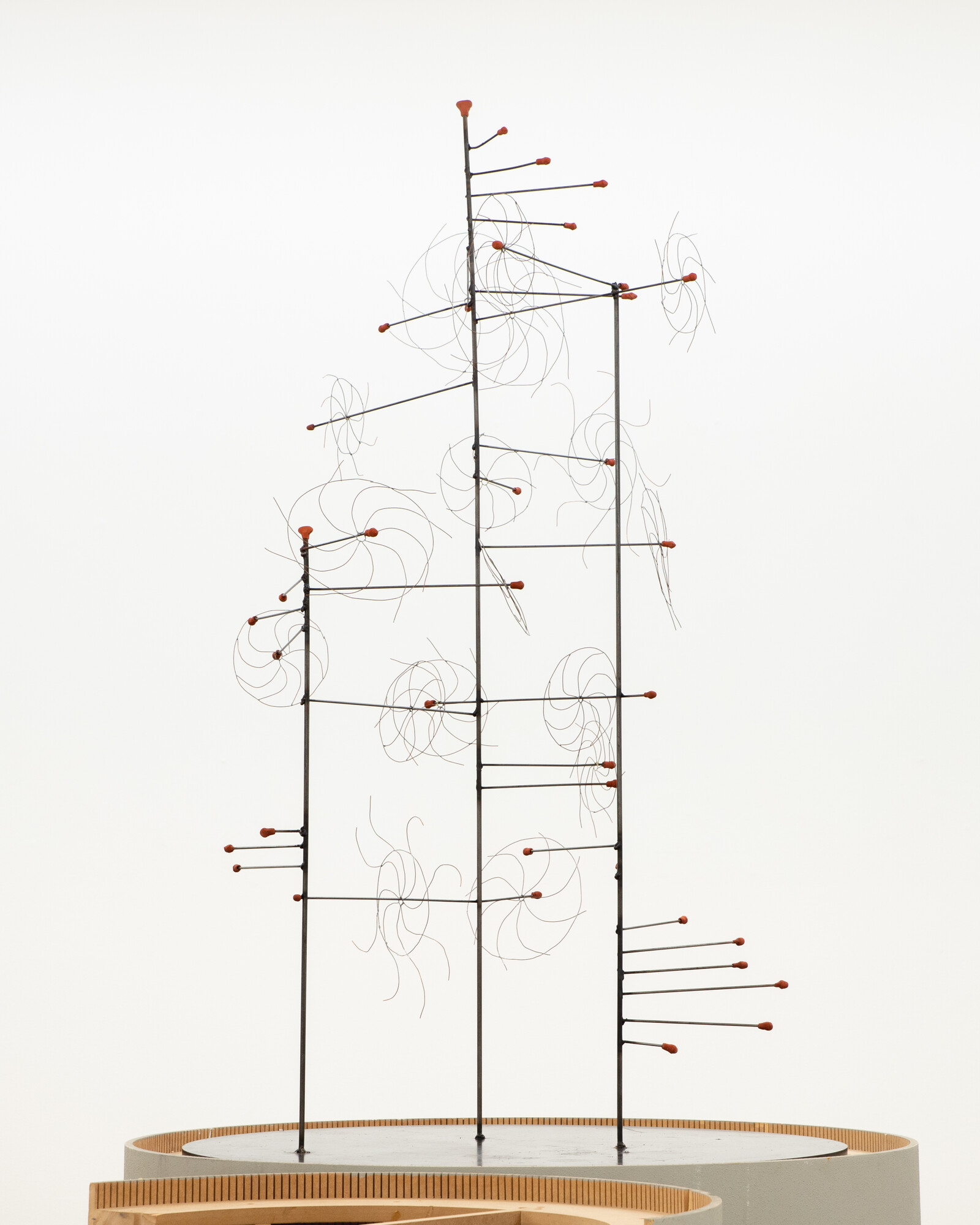

Atop a half-moon plinth, an open can of gin sits fleetingly below a carnivalesque, wind-chime-y chemistry set titled I invented modern agriculture (2023). A staircase of soldered steel and clay-tipped Q-tips ascends and dips, holding Vaughan’s signature pinwheels at each level. I recognise these forms from the overturned farm equipment within her sprawling installation Ogives(2020), installed at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art as part of Overlapping Magisteria, a group exhibition of the Macfarlane Commissions. The pinwheels politely resume the arrested spiralling of the cyan drill-bits that lie on the concrete floor. The right judgment is required to calculate how much counterweight to apply to pull a needle through the grooves of a 45” record. If wind were allowed in to propel the music, it would appear in glass, drills, literal drums, clock-ticks, and creaks—a barn dance beneath the exposed rafters.

The dance comes to a hushed stillness. The complex posture of another spindly sculpture, Third hand: Wahlenbergia Communis (2023), contains blue Apoxie Wahlenbergia flowers and artificial fly-shaped fishing lures that are astutely connected using metal clamps, wire, and replacement bike parts. Each element looks kinetic and spry. It implies movement but is frozen in a moment of intimate privacy. The imagery evokes an etymological archive of bugs pinned in place, with fishing lures blooming brightly at the ends of some stalks. Later, I watch a video during a dinnertime YouTube surf where a gruff Yorkshire fisherman demonstrates how these lures are made, revealing their thread-bound, learned invertebrate intricacies for my naive eye. Once again, movement is implied, but the result remains static. I can’t help but wish to see these works in motion, although I recognise the potential damage this would cause them. It’s ironic that this art concerned with the flux of ecological conservation must, for the purposes of conservation, stand still.

I once worked at a store selling candles in ceramic canisters, where we told customers to pour hot water into it once the candle was spent, then let the cooling process lift the residual wax into a disc, making it easy to scoop off the surface. The same process comes to mind as I peer at the base of Pistil—a supersized disc of beeswax that sits atop a supersized canister. Pistil itself rests on its waxy bed in beanbag-like repose. The tripartite form, seen in the entryway’s first floral piece, reappears in its three connected “blobjects” conjoined around a single nucleus. These anthropomorphic elements, whilst not quite personified, share a Stoic philosophy that engages them in a closed, eudaimonic conversation. I find myself wanting to eavesdrop on their worldly gossip. In the room behind, Michelle Ussher’s wall-mounted ceramics murmur in response. Their glazes are layered with a bubbled, painterly sensibility that arguably surpasses the candy-coloured paintings they accompany.

In a sensorial exhibition like Rumours of True Things, the neuroscientific phenomenon of cross-modal correspondence is prevalent. This concept can be exemplified by the Kiki-Bouba effect, where ninety-five percent of people associate the word “Kiki” with a spiky star shape and “Bouba” with a rounded, bulbous one. These categories can be applied endlessly. For example, the spindly Third Hand series dotted around the gallery is, for me, undoubtedly “Kiki.” Vaughan skilfully integrates this understanding, evident on a macro scale in A nature seen beyond belief, instead of a moderately accurate fish tank, where a lilac tulip cup forms a child-sized parapet that’s inaccessible via the dance pole that supports it. The “bouba-ness” of the cup is powder-coated, ready for the playground and, perhaps unexpectedly, the strip club. This form reappears in Suburban life—a squat, Bunnings-green drum with moulded plastic divots that give it a wide stance on the floor. Petal shapes, seemingly manipulated by heat, partially enclose its top. Ceramic copycats like The unsubstantial can easily bump the ordered world into very different registers (2023), and We end up with something partial (2023), resemble nigella seedpods with their ribbed bulbousness.

The conversational text accompanying the show by Gabriel Curtin, titled Third Hands, Second Lives, mirrors the exhibition’s gently lilting tone. It begins by contemplating the lifespan of lobelia seeds to our own, leading to the reflection:

“To some it’s just a purple flower, to others, a miracle seed, for others still, a landing pad. From our vantage, we try to hold all these scales at once but this is mostly impossible. We end up with something partial, with rumours.”

We can never really know, but we can observe things within their balance, contrived or natural, and know something is true. Whether you appreciate the delicate or the derelict, the show is open for its last day today.

Ella Howells is a writer, artist and arts administrator based in Naarm/Melbourne.