Zac Segbedzi: Collectables; The Show About The Show; Sex is Gay (Part Deux)

Cameron Hurst

The first time I go to Guzzler, the art historian David Homewood answers the door. Homewood is rakish and bespectacled, wears a pinstriped shirt buttoned to the collar and has a chain smoker’s complexion. He looks like a handsome human cigarette.

“Come in, come in, come in”, he says, bobbing up and down slightly. As he turns, the small of his back appears through a gigantic tear in the back panel of his shirt. I follow him through the house, down the garden path and into the gallery-shed. A photography show by the artist Zac Segbedzi is on. Segbedzi had recently returned to Melbourne after a stint in the US, presenting a solo exhibition at Jenny’s in Los Angeles in mid-2019 and assisting the artist Mathieu Malouf. In the Rosanna gallery, the glossy pictures are mostly of flesh (plastic and/or real) arranged in staged contortions: a man’s arse held aloft and stretched taut by a pair of disembodied hands; Barbie embracing a Ken doll with a plastic penis in the place of his head; an elaborate crucifixion of a woman in a neon-yellow thong, framed by a bouquet of acid-bright plastic flowers.

Two adult appropriations of the German photographer Heji Shin’s Baby (2016) series are particularly arresting. In one, featured on the poster advertising the show, Segbedzi’s face is partially visible through the pink flaps of a silicone vagina. The artist’s bloody hands stretch the orifice open from the inside—a gory inversion of the arse picture—to fix me in place with a single, beady eye. In the other image, a more primal scenario, Segbedzi’s shaved, blood-smeared head crowns. It feels like witnessing a well-lit, self-administered rebirth.

We exit the gallery and sit on wobbling chairs in the yard. Although Homewood notes apologetically that he has not slept for days, he gives a far-reaching and erudite oration on the works and their connection to various local and international artists and artistic traditions. He is still thinking about the title. “Come on”, he drones, “What do you think?” I don’t really know what to say. The show is titled Sex is Gay. Apologies: actually, Sex is (censored). To be honest, I feel out of my depth, but I’m interested.

That was last year. A few weeks ago, three new Segbedzi exhibitions opened. Each had a different gambit, but they shared certain preoccupations and tendencies: Daedalian sets of references, a combination of meticulous construction and display with graphic, often abject, sexual content, and a grappling with the inescapable provincialism of Australian art. All three were really good.

single channel video loop, 01:15, Guzzler, Rosanna. Photo courtesy of Guzzler.

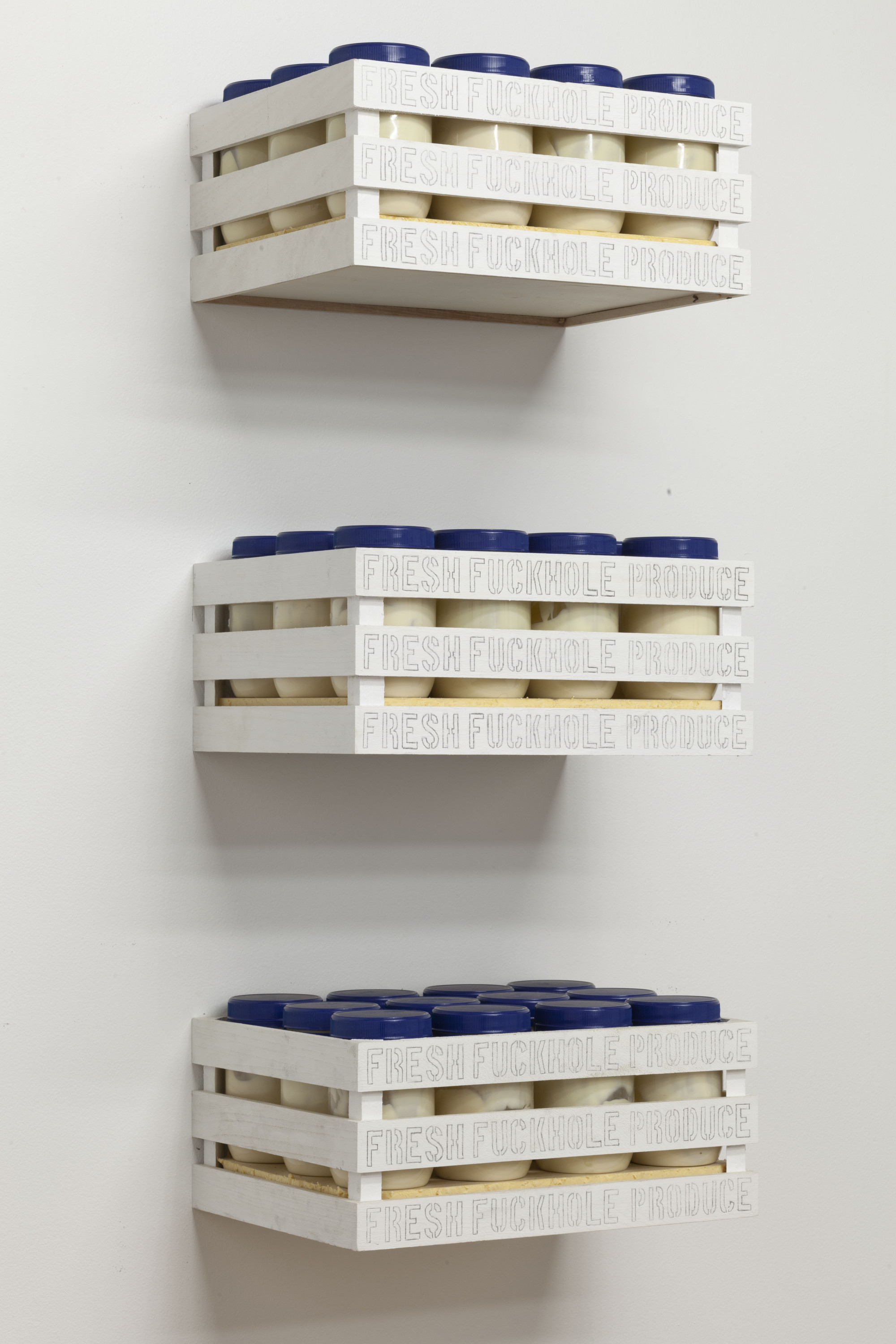

Sex is Gay (Part Deux) showed at Guzzler. This time curated by Segbedzi, the group show brought together five US-affiliated artists and resident mayosexual Alex Vivian. Semen and celebrity were recurring themes. There were two videos, two digital prints, two collages and a Donald Judd meets Whole Egg wall work. Spaced vertically, a set of three crates labelled “FRESH FUCKHOLE PRODUCE” held distinctive royal blue-lidded jars. The vessels faced a littering of pages torn from of an art-porn shoot by Ramsay Alderson, Richard Hawkins and Mathieu Malouf, and the latter’s grainy video of the Kardashians rolling around in a studio. In the smaller room adjoining the main gallery, a video by the mysterious Alderson played. I was pleased to discover that the appendage being thrust repeatedly into a vacuum was not, as I had previously thought, a particularly veiny forearm. Ejaculation confirmed this. Enchantée.

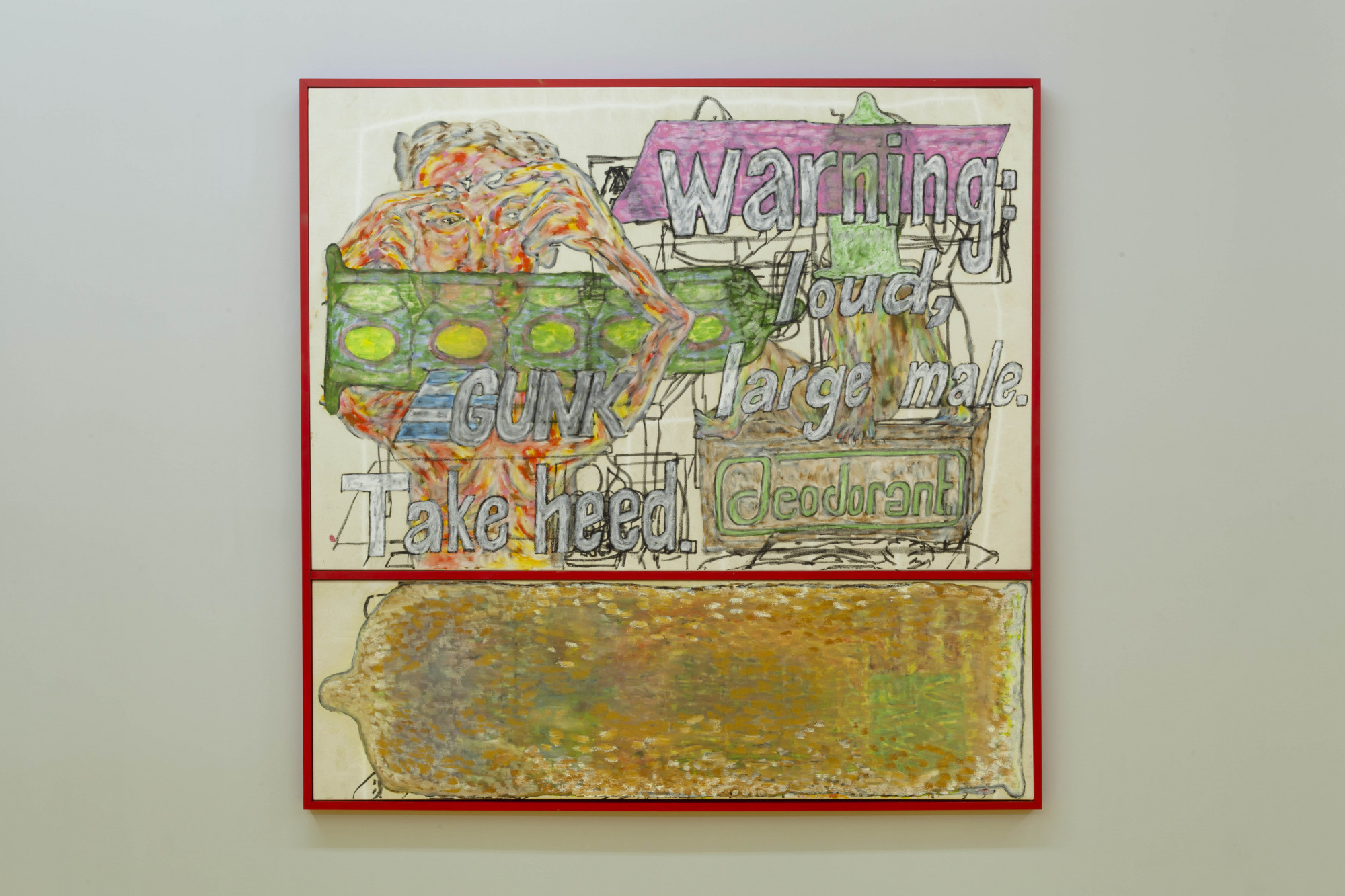

The Bourke Street Neon Parc hosted The Show About the Show in the backdrop of frenzied “Kill the Bill” anti-vaccination protests. There was a covidy ambience in the air. Several paintings by Segbedzi were on display. The newest were modelled after Yves Klein’s Relief Éponge Bleu series, albeit with brown replacing blue and foam faeces replacing sea sponge. These were hung alongside works on paper by subcultural Australian artists, expatriates (excepting Meatdog) who made careers overseas before returning to varied acclaim. There was also a Martin Kippenberger screenprint (the German artist’s prolific, multivalent output seems central to Segbedzi’s artistic lexicon) and a collection of pasted-up figures and posters. Many of the paste-ups were true to the exhibition title, leveraging the inner-city real estate of the gallery to advertise Sex is Gay (Part Deux) and Segbedzi’s third and final show of the weekend, Collectables.

This was held at Centre D’editions, a freshly minted enterprise at the Paris end of Gertrude Street. Collectables advertised a group of artists so random—Pop Art superstars and 80s Australian art heroes next to recent VCA graduates and Virgil Abloh (RIP)—that the show seemed too good to be true until I saw it arranged carefully in the gallery. The Koons wasn’t as shiny as I thought it would be; the Vo was amazing. The Centre is a collaboration between Segbedzi, artist Evie Poggioli and gallerist Howard Palmer. The trio built the space together inside the ground floor of a warehouse owned by Segbedzi’s (until recently, absent) father, the real estate developer Daniel Besen. It looked great, with high ceilings, a primary yellow floor, grey walls and a caution-striped industrial fit-out reminiscent of Manchester club The Haçienda. Segbedzi, Poggioli and Palmer all contribute to the gallery’s shop, which stocks limited run graphic t-shirts in addition to such merchandise as roach-paper sheets, bumper stickers and a fake MeMO Review Press Pass. Art in the main gallery space was also for sale. “While some of these works are out of reach, many are surprisingly quite attainable!” the room sheet read. “Collecting is fun!”

Looking at the sheer volume of people, objects and places in Segbedzi’s shows can sometimes make a viewer feel as though she’s being gunned down by a semi-automatic artistic reference rifle. Across the Guzzler, Neon Parc and Centre D’editions exhibitions appeared, in no particular order, Angela Merkel, Khloe Kardashian, Joseph Beuys, Jenny’s, Nina Hagen, Tom Faulk, John Mayer, Berlin graf, Caveh Zahedi, Emma Stone, Supreme, Juan Davila, Sol LeWitt, Carine Roitfeld, Nick Cave, IKEA, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, @helen_retouch, Sofia Coppola, Dimes, Suicidal Oil Piglet and Martin Sharp. Palmer, Poggioli and Homewood are also represented. This observation of mass is not to say that the references were arbitrary. On the contrary, they were all considered. There were also certainly references that I didn’t recognise, lobbed elsewhere. Segbedzi’s work is directed towards multiple audiences; there is an almost tentacular manner to his distribution of signifiers, chosen to elicit responses from Europe and the US as well as Melbourne.

Some references ricocheted across the different exhibitions. Andy Warhol’s shock of white hair appeared in Neon Parc, his life-size figure pasted up high horizontally. A Warhol work was displayed in the Collectables cabinet, a volume of photographs by an acolyte printed on phonebook stock so fragile as to be unopenable. His most famous mode of production also appeared in Centre D’editions—the t-shirts all screen printed in the warehouse space behind the main gallery. It was a Factory of sorts. According to his biographers, when screen-printing, Warhol did not want a perfectly clean image. Instead, he preferred “the trashy immediacy of a tabloid news photo”. Printed tabloids are now essentially defunct, but there was a clear “trashy immediacy” to the imagery of the Centre shirts. Many designs seemed ripped from the ephemeral pages of blogs, sketchbooks and forums (there is also a strong B-movie poster theme). Recently, wearing one of the shirts at a bar, I was stopped by a bleach-browed girl wearing a teal Calvin Klein push-up bra as a top. “Oh my god, I want one!” she said. The barely legal club rat market seems secured. Will more financially solvent collectors buy the paintings?

Another important Warhol reference was Raid the Icebox I, the artist’s excavation of the Rhode Island School of Design’s permanent collection in 1970. Warhol placed a disparate selection of museum items—a Whistler etching, silk opera pumps, Diné (Navajo) woven blankets—in a stacked display. It was curation-as-context creation, the formation of a new understanding of artworks through relational exhibition. In The Show about the Show, Segbedzi took a similar approach to an unofficial icebox of Australian subcultural figures. “I wanted to show works of older artists who may have directly or indirectly shaped the artistic world i inhabit”, he wrote.

One such artist is Vali Myers, who moved from Australia to Paris in the 1950s. Myers was the central figure in the photobook Love on the Left Bank (1954). Two decades later at the Chelsea Hotel, with a “live fox on her shoulder”, Myers tattooed a lightning bolt on an awed Patti Smith’s knee. At Neon Parc, a laminated poster of a Myers drawing titled Black Shaman in the Sun (1968) was, as her gallery trust website describes it, “pure fire”. The picture shows a crimson-haired woman sitting with a fox in a gothic woodland scene. The inclusion of this kohl folk kitsch is weirdly sweet; it’s more reminiscent of the painstaking feminist art-historical tradition of rediscovering undersung women artists than Kippenberger bad boy antics.

In 1974, the art historian Terry Smith wrote in Artforum that there seemed to be “no way around the fact that as long as strong metropolitan centres like New York continue to define the state of play… all the other centers will be provincial, ipso facto”. Is this still true? Centre D’editions approached the provincial paradox—that the provincial artist, expatriate, returnee or otherwise, “cannot choose not to be provincial”—through invoking New York. The city served as a proxy symbol for metropolitan centers (which have their own myopic tendencies) more generally. The Centre D’editions bumper sticker, designed by Palmer, began with the ironic prostration “I <3 New York”. In the posters for the show, the Statue of Liberty was personified by a teal-skinned pole dancer. She swung around in the darkened construction site of the gallery, wearing glasses and oxidised woolen leg warmers.

The Statue reappeared in the exhibition in the Danish-Vietnamese artist Danh Vo’s We The People (detail) (2010–2014). Vo’s sculpture forms part of a larger series of 250 fragments of the New York landmark cast in two-millimeter-thick copper. They are to scale and made using the same manufacturing techniques as the original. The one in Collectables was an undulating fabric segment that showed traces of exposure to the elements; there was a streak of bird poo, and spatters of oxidation had begun to change the colour of the curved panels. We The People (detail) was free of text and was the least obviously figurative work across all three shows. Speaking about the project, Vo has said that he was adamant that the Statue didn’t need more interpretation. “I think what is beautiful about art is it is one of the rare fields where you are just creating something, you know. Purely, first of all for my own sake and then some strangers out there—just one, you know—catch up on it. Isn’t that beautiful?” It is. We The People was a contemplative, ambiguous respite in the jizzfest.

I contemplated. Segbedzi’s output can sometimes feel like a series of semiotic flinch tests, but it is ultimately as thoughtful as it is (censored). Sex is Gay (Part Deux), The Show About the Show and Collectables make him, for now at least, the best artist-cum-curator in the greatest city in the world. The Empire city, the city of dreams, the city that never sleeps, the city so nice, they named it twice: Naarm/Melbourne.

Cameron Hurst is a contributing editor of MeMO Review. She is editing the upcoming issue of INDEX JOURNAL, Secession, with Giles Fielke.