Bodies of Work

Cameron Hurst

“Disappointment is the governing affect of feminism”, writes Andrea Long Chu. Feminism invariably lets us (lesbian/Marxist/Black/ queer/trans/Twitter feminists) down, she says, by proving time and time again its status as polymorphous fantasy in relation to whatever change we had hoped it would bring about. In this way, Bodies of Work, a film and lecture program on women and labour curated by Benison Kilby and hosted by Bus Projects throughout September, was deeply disappointing. I loved it.

Bodies of Work continued the agenda of the eponymous show held at Bus in 2019, back when IRL gallery space existed. The films spanned diffuse subjects. Taken as a whole, they made the case for considering women’s artistic strategies for addressing exploitative working conditions of the past in relation to contemporary conditions of gendered neoliberal precarity. Undervalued social reproduction and feminised labour conditions were endemic pre-COVID. The virus has only intensified the structural disparities in Australia’s inequitable service economy. Women workers, many of whom are migrants, have borne the brunt of the pandemic’s havoc; data on the distribution of infection has reiterated the life-threatening status of frontline care work. Bodies of Work looked to strategies of the past to understand our precarity in the present.

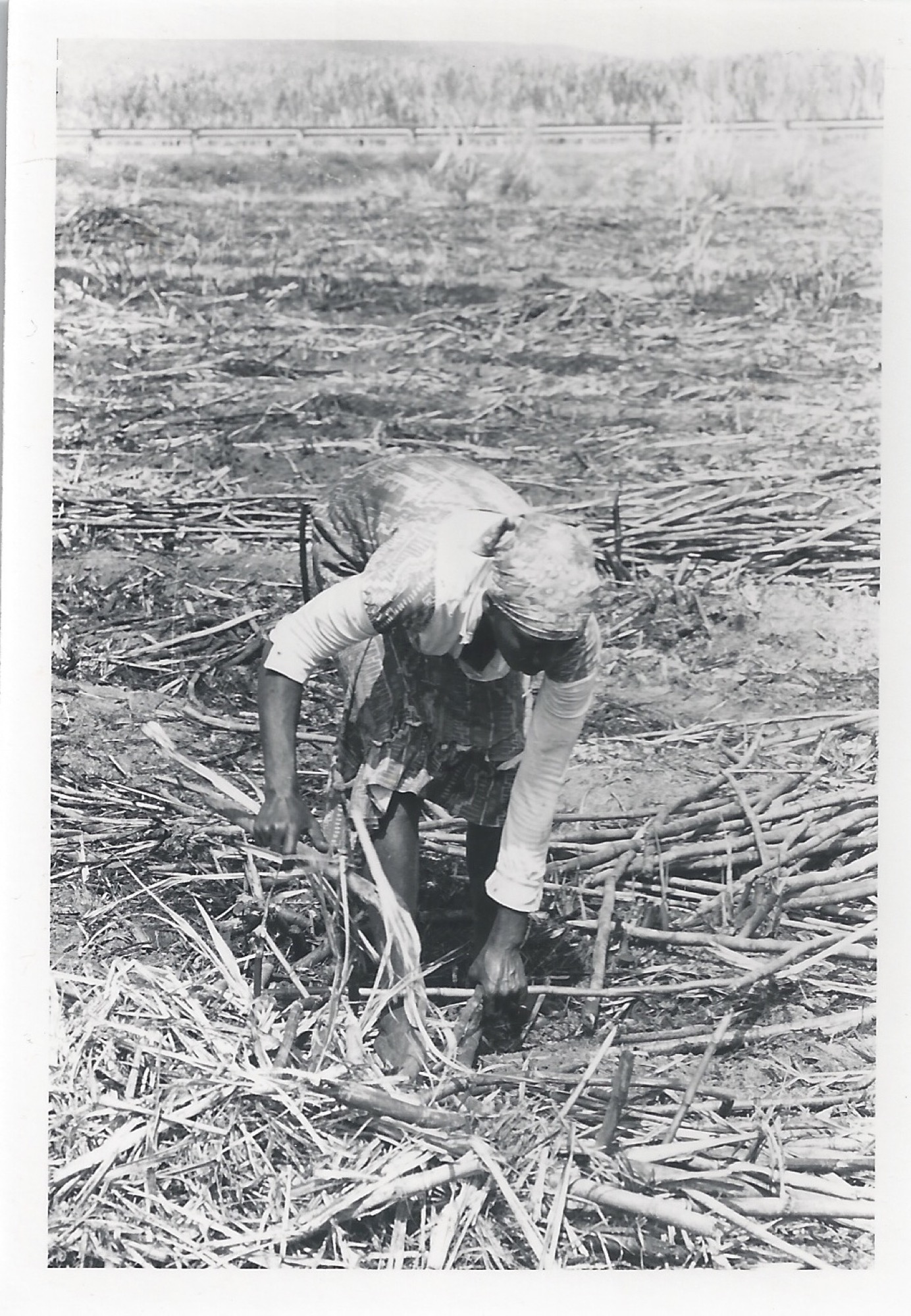

Each of the four films documented a radically different group of women. Scuola Senza Fine (1983) focussed on participants in the “150 Hour” project in Milan, a union initiative started in 1974 that provided a free higher education for workers. A standout in the series, Sweet Sugar Rage (1985), captured the experimental theatre practice of the Kingston-based Sistren Theatre Collective. With great candour and empathy, Sistren engaged women working on a brutally exploitative sugar plantation to create an interactive play that re-staged their real life labour conflicts to practise negotiating for improved conditions. In the UK, All Work and No Play (1976) pushed for a radical “Wages for Housework” campaign. The serenely uncanny, gloss-haired leader of the Power of Women Collective argued with didactic conviction that the unpaid labour done at home is crucial to sustaining the flow of capital. Finally, Women of the Rhondda (1973) is a sobering set of four oral histories documenting women’s lives during the brutal miners’ strikes in South Wales in the 1920s.

Siona Wilson, a New York-based art historian who has recently published Art Labor, Sex Politics: Feminist Effects in 1970s British Art and Performance, delivered an online lecture accompanying the last week of the program. Wilson contextualised Women of the Rhondda in the oeuvre of the Berwick Street Film Collective, a groundbreaking group of feminist filmmakers that included the conceptual artist Mary Kelly. The Collective’s work was deeply connected to the historical moment of England in the 1970s, when events as disparate (or not) as the Ford sewing machine workers’ strike of 1968 and the widespread dissemination of Anne Koedt’s essay The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm galvanised a period of militant feminist political organising. The concerns and sensibilities of Women of the Rhondda and the other films programmed in Bodies of Work felt foreign to a contemporary viewer, but moments of resonance emerged from the complex representations of relationships between gender, capital and culture.

In Victoria, there is a long history of collaboration between the labour movement and the art world. The most obvious example of this is in the fraught relationships between the card-carrying Commies and the intractably bourgeois Heide modernists, who oscillated between comradely devotion to and iconoclastic rejection of artistic solidarity. Moments of collaboration stand out, like Noel Counihan and John Reed’s collaborative Anti-Fascist Exhibition held in 1942 at the Athenaeum Gallery. Another critical moment of action can be found much earlier, in the work of the Wurundjeri ngurungaeta (leader) William Barak. The influence of the fierce campaign for commercial control of the hops production at Corranderrk station in the 1870s and 80s is sometimes underplayed in art historical accounts of Barak’s painting, but his visual assertions of Wurundjeri culture are deeply connected to this labour struggle. The Art and Working Life program (facilitated by the Conceptual artist and writer Ian Burn, among others), based at Sydney’s Trades Hall in the 1980s, is another key touchstone.

Of course, neither Counihan, Barak nor Burn’s artwork stymied the noxious creep of viciously anti-working class public policy and union erosion that has characterised the last 40 years of Australian working life. Much like feminism, art that hopes to substantially shift labour conditions often disappoints. The program presented by Bodies of Work screens in knowing succession to these histories. It sits as part of a new surge of critical attention to intersections of art and labour, a loose coalition of recent responses and revisitations of art workers’ continually worsening material conditions. The 1856 project, the State of the Union exhibition at the Potter, the fantastic Workers Art Collective and Kay Abude’s POWER performance at Buxton Contemporary come to mind. Half the work on the Bus Projects homepage invokes worker-adjacent conceptual concerns, and at West Space the current exhibition includes Georgia Robenstone’s two-channel video work, titled Power Without Glory, after the iconic Labor hack take-down novel by Frank Hardy first published in 1950.

Kilby’s curatorial practice is an important contribution to this turn, while Bodies of Work continues her attention to the particularities of women’s labour. This takes many forms. Much of this labour is not even considered work within conventional Marxism, an oversight rectified by the invocation of frameworks of “care” and/or “social reproduction”. These emerge in the ongoing feminist paean for the domestic, reiterated in the spatiality of the films. Labour takes place in kitchens, in living rooms, and at dining tables. The women in Scuola Senza Fine (School Without End) make space for their intellectual work amongst “the tangerine peels, teacups”; All Work and No Play opens with a minutely documented scene of a working woman brusquely cooking, feeding, washing, wiping, sweeping, tidying and packing up around her two children in a very British kitchen, before heading off to her paid labour; in the mining community depicted in Women of the Rhondda, the gritty camera lingers over mantelpieces stacked with accoutrements that testify to generations shaped by the pits.

I screened the films in my living room, in the fugue of my domestic pandemic purgatory. In some perverse way, this isolated confinement functioned as a covid-safe re-enactment of the old “problem which has no name”. The importance of feminine social networks where women’s labour is valued became even more apparent. Spaces where women can come together and talk are completely transformative for the subjects of each film. To speak in the parlance of the Second Wave, the program is a collection of celluloid consciousness-raising circles. The visual is always in service of the verbal. The films become sites to listen in on oral histories; on gossip, confession and commiseration. The Rhondda Women’s Guild is “an outstanding organisation”, lilts one interviewee from her armchair. Conversation is far from uniformly uplifting. “We’ve only been liberated to work harder”, moans a woman in All Work and No Play, “that’s all that Women’s Lib has done”. (Promise liberation; disappoint). A circle of polyester bell-bottomed women around her murmur empathetic assent.

In Scuola Senza Fine, frenetic dialogue bounces around a table piled with ciabatta and cheese as women raucously recount the sense of community and autonomy they gained from joining the union’s education program. After the school officially ended, they couldn’t bear returning to their old lives. Amalia Mollinei recounts sardonically how, now, “every Friday we prepare and assemble to organise a two-year study program for women who are living in a blissful state of ignorance”. (Often, knowledge does not equate to power. Cue disappointment). Yet it’s difficult to believe that ignorance was really bliss. Striding through the streets of Milan, the women in Scuola Senza Fine fill the screen with experimental re-enactments of texts they have written ruminating on subjects as varied as urban planning, the psychoanalytic structure of maternity (it isn’t an etymological coincidence that we refer to childbirth as “labour”), and the impact of industrialisation in Italy. In my favourite scene, one of the women runs back and forth through a spotlight on a darkened stage, unpeeling Rococo frilled sleeves. It’s bizarre. The oddly captivating vaudeville serves no productive purpose. It’s just a staging of one woman’s joyous artistic practice—a worker’s right.

The subjects in Sweet Sugar Rage stage re-enactments of women’s stories for emancipatory negotiation skills, not joy. A member cheerfully outlines their dramaturgical method from the back seat of a car driving to the sugar plantation. The group “encourages women to act out their experiences, analyse them, and search for common solutions”. It is deeply committed to optimism (the practice of staving off disappointment). The farm workers, whose bare hands and feet are charred by fertiliser, are exhausted by the gargantuan demands of their paid and unpaid labour. Their working conditions seem both untenable and unalterable. It was enough to send me grimacing into alienated despair. But the buoyantly collaborative Sistren Studios Theatre Collective are stronger than me. They conduct probing interviews with great care, transforming the women’s stories into a well-attended production that concludes with a tensely energetic debate about how to go about demanding higher pay. By Sweet Sugar Rage’s conclusion, the ultimate efficacy of this Brechtian operation is unclear, but the fiery engagement of the participating women is undoubtable.

In her lecture, Siona Wilson chidingly framed the Berwick Street Film Collective’s attempts at harmonious intersectionality as “aspirational”. The gap between the white, middle-class filmmakers’ and the clumsily discussed abject poverty of their working class subjects was essentially unbridgeable. The functional inability of their experimental film practice to meaningfully alter labour conditions outside of representation was jarring. I think aspiration is a fitting word for this dynamic. It connotes a certain naivety: a wilful over-investment in the effectiveness of art as an instrument of political action. This is a paradigm which is not inapplicable to myself and many other strivingly well-meaning participants in Victorian art communities. It is often easier to diminish individual proximity to institutionalised whiteness and access to resolutely middle-class cultural, if not financial, capital, than to undertake sustained action that addresses these structures. Art is not a substitute for the slog work of organising. The paradoxes generated by politically-minded art—of intention and effect, authenticity and incommensurability, representation and tokenism—are difficult. They demand a tensive scrutiny that can’t be tidily resolved.

Wilson’s critique sat uneasily with my fantasy for the potentialities of Bodies of Work, which I had hoped would catalyse a roaring return of the Australian trade union movement, profoundly reshape how our culture perceives and values women’s work, end neoliberalism, and bring back consciousness-raising as a “school without end”. Maybe I’m deluded. Or aspirational, whatever. I am sure to be disappointed. To project these desires onto art is fantastical. But, as my paragon of This Wave feminism, Long Chu, says: “The question is never how to get rid of fantasy; the first and last fantasy, after all, is that fantasy is something you can do without”. The films that comprise Bodies of Work are idiosyncratic. Each refutes the visual language of agitprop, instead experimenting with what it can mean to use film to pay attention to the subjective experiences of women’s work. This is the feminist project of collective mythmaking: constructing utopian solutions to the conditions of a time and place, together.

Each Saturday in September, I tuned in for the screenings and experienced a deep reverence for the ambitions, sorrows, intimacies and sheer toil of women who have worked before me. I started working on this text. A scene of communal exuberance in Scuola Senza Fine stuck in my mind, where the women are gallivanting around a kitchen table, accompanied only by a single harmonica. On the first Sunday of October, the new 21 Savage and Metro Boomin’ album is released. I’m not a liberated 1970s Italian housewife; harmonica solos won’t do it for me. I cranked Savage Mode II in my headphones. Over a trap beat, after Morgan Freeman provides the intros, a woman’s voice drawls an exemplary Marxist-feminist precis with fortune-telling clarity: This world is all about money, and pussy. And you need to figure that out. Yes. And then what? Bodies of Work is one voice in the conversation of continually figuring it out, such that each time we’re disappointed, it’s new.

Cameron Hurst is a writer based in Narrm/Melbourne. She is writing an Honours thesis in Art History at the University of Melbourne.