Baldessin/Whiteley: Parallel Visions

Victoria Perin

Together George Baldessin and Imants Tillers represented Australia in the 1975 Bienal de São Paulo. Although Tillers was 25 and Baldessin eleven years older, the artists bonded closely: “George represented the more conservative art world I had just decided to abandon,” notes Tillers in an interview with researcher Nicole Bowller from 2016, “but in fact, he kind of made me appreciate it again”. While in Brazil Baldessin, a charismatic charmer, befriended German artist Sigmar Polke. Polke and Baldessin were roughly the same age, “we used to have drinks every evening … (Polke) was attracted to the Australian contingent. (This entourage included Mervyn Horton, the Australian Commissioner for the Bienal, and Rudy Komon, Baldessin’s dealer)”. Later Polke would visit Australia in the early 1980s and have a career-altering experience seeing (and filming) the red sand at Uluru. The mid-career pivot (inspired by travel, landscape, art or whatever) is a narrative tragically closed off to Baldessin. Had he been so inclined, Polke couldn’t catch-up with his colleague in Melbourne while in Australia, as by this time Baldessin was dead.

Imants Tillers, his wife Jenny Slatyer, Baldessin and his wife Tess all established themselves in Paris after São Paulo. There they saw an incredible series of exhibitions on the European avant-garde including Harald Szeemann’s The Bachelor Machines and Francis Picabia’s major 1976 retrospective at the Grand Palais. George and Tess were in France until 1977 and saw the inaugural exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, the influential retrospective of Marcel Duchamp, the same year. “I think George would have had a second life as an artist,” speculates Tillers, “if his life hadn’t been cut short, because in a way his work also relates to the Italian transavantgarde… I think his Italian background fed into his work, he studied there, he would have identified with it, (albeit) secretly”. The transavantgardia movement was recognised in the early 1980s as a lyrical turn away from Italian conceptualism, and gathers together artist such as Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, and Mimmo Paladino.

I bring up Tillers’ recollections of Baldessin in São Paulo and Paris because I believe these few anecdotes, contextual stories about what Baldessin was viewing and who he was befriending, give us a model of art-historical connections that are at least as valid and maybe more intriguing than the model that is being presented by guest curator, the prominent art historian Sasha Grishin, in the current exhibition Baldessin/Whiteley: Parallel Visions at the National Gallery of Victoria. While it is a complete joy to see Baldessin’s prints and sculpture being displayed in Melbourne so beautifully and comprehensively, the context that we are being invited to view them – a twinning with perhaps Australia’s most famous artist, Brett Whiteley – ultimately disappoints.

Tillers also offers revealing speculations about Baldessin’s actual milieu, as opposed to an imagined internationalist context:

I think he could have moved out from his circle … (H)e was easily the most charismatic artist and I think in a way, his art was held back, I mean that group was very important, but I got the feeling he was so interested in me because it was an escape route out of what he could see was a dead end. I felt like George was very ambitious. It is such a tragedy that he did not get the chance to develop that. To me he seemed quite open to entering other art worlds, not just the RMIT world in Melbourne.

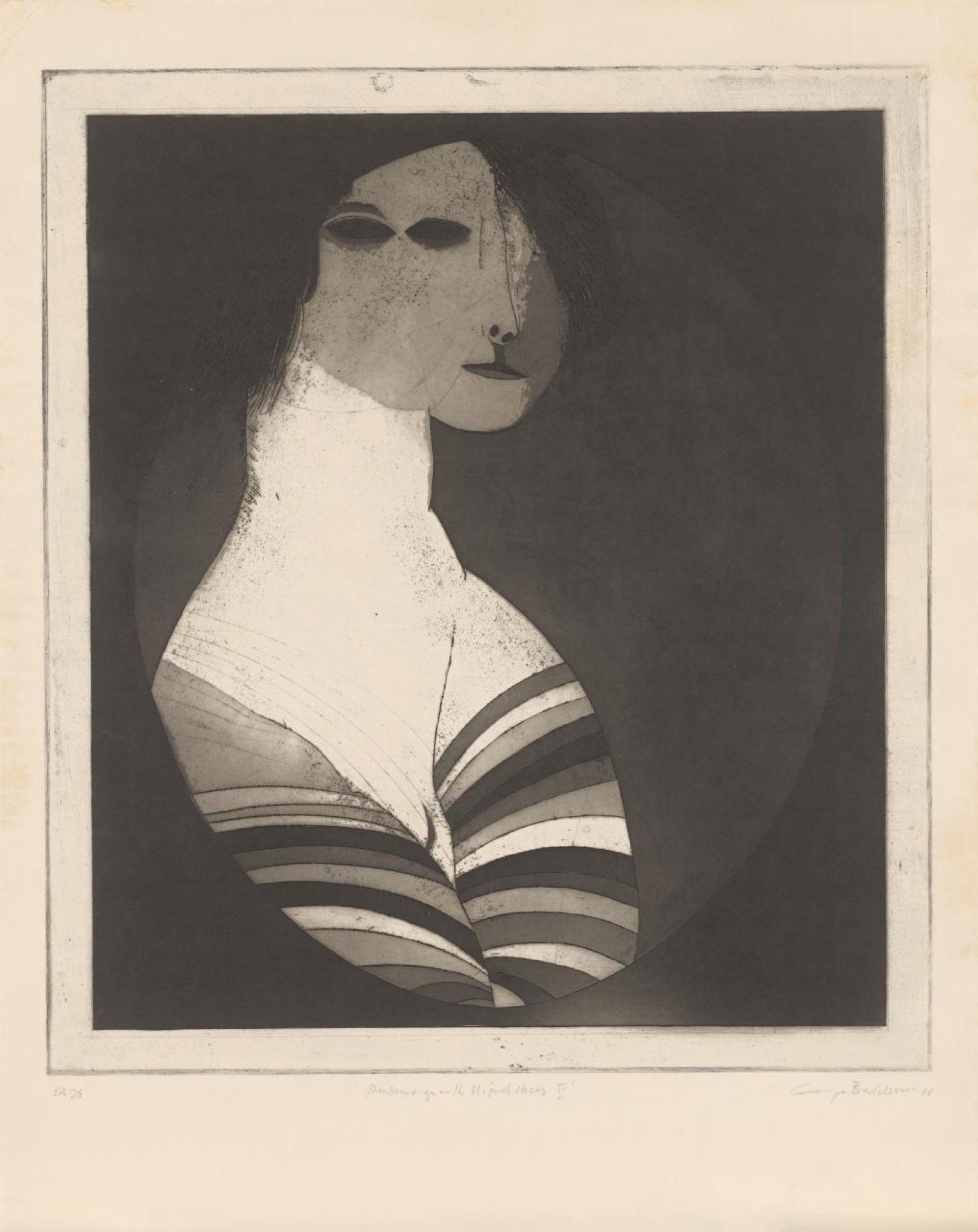

In a sensitive reversal of the traditional artist-mentorship, in which the student may venture to teach the teacher, Tillers here offers the model of the relationship between young avant-gardist Ian Burn and the mid-career Fred Williams. Baldessin’s circle, the “RMIT world”, as referred to here, was a strict boys’ club that dominated the teaching and socialising of the artists at RMIT in the 60s and 70s. This crowd was especially engaged with printmaking. Baldessin, in particular, was king of the aquatint, a technique that allows his prints to shimmer with a resplendent variation of greys and blacks. His position in this community, and his acknowledged skill, has defined Baldessin’s reputation ever since his death at age 39.

That Tillers would suggest it was this very context that “held back” Baldessin, is a major gear-shift in our view of the artist. Perhaps it is with similar motives that Grishin decides to show Baldessin outside of his immediate context, in comparison with Whiteley, the globetrotting Sydney maverick.

In case it is not yet obvious, this is a review of Baldessin/Whiteley as predominately a discussion of Baldessin. But it’s not just my own bias (it should be said that I completed a thesis on Baldessin under Professor Grishin); it will not take a visitor long to note that there is something off about the numbers in this exhibition. It appears, until the very end of the show, as if Baldessin’s work dominates Whiteley’s in both sheer numbers and arrangement. This begins in the entrance nook, where Baldessin’s sculpture Pear Versions (several of which are hybridised together here) cover and crowd our view of Whiteley’s Evening Coming in on Sydney Harbour (1975). An unsuspecting visitor, drawn by Whiteley’s fame, may feel the part of the reluctant pet, with Baldessin the pill you are being asked to swallow with the slice of ham that is Brett Whiteley.

It remains for some other viewer to decide if Baldessin is a flattering foil for Whiteley, because I took as my task to find out if the latter provides a useful context for the former, the underdog to Whiteley’s considerably more glamourous reputation. As Grishin presents the artists, their resonances are three-fold: the artists were the same age (“Born forty-two days apart” conspiratorially whispers the catalogue), they were both resolutely figurative artist who consistently depicted the human (female) form, and they each offered responses to their cultural zeitgeist, exemplified here in gestures to pop-art, existentialism and 1960s art-cults. The men were both lords of their home-turf, the personifications of the stylistic preferences found in Sydney and Melbourne. Then there’s also the fact that their bulging and haphazard draughtsmanship can look uncannily similar (and this is most likely due to a naked theft from mutual cornerstone, Francis Bacon). As Baldessin and Whiteley did not personally know each other, these resonances are offered in lieu of the more stimulating rivalries of, say, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, two friends who pushed and enriched each other, and whom Grishin mentions as an analogous model.

The stated resonances between the artists are clear and visible in the show. Yet after the first two enjoyable rooms, the superficial connections cease to convince. Whereas Whiteley’s images ascend to some almost painfully unselfconscious heights, Baldessin remains oblique and technically preoccupied. I’ve never seen Baldessin’s work look more furtive and aloof as it does when put in direct competition with Whiteley’s squawking flamboyance.

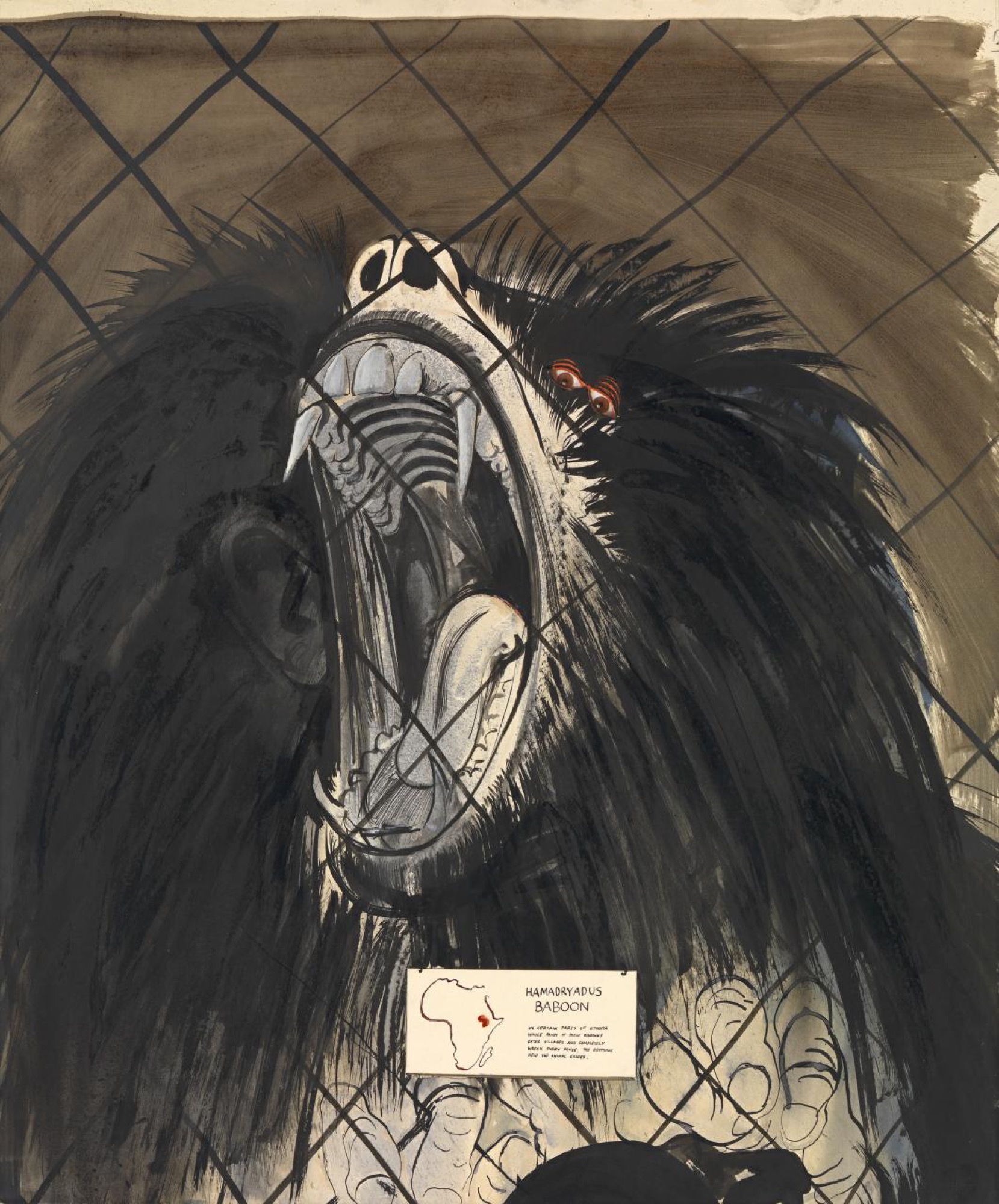

Then there are resonances that are unpleasant and unflattering to both artists. The Australian art community in the 70s was the last time charismatic male artists were allowed to hold court with impunity. This exhibition replicates this kind of seventies’ vision of success uncritically. An example of this is at the heart of the exhibition. Whiteley’s murderous Christie works are paired with Baldessin’s charcoal drawings of MM, a Mary Magdalene/sex worker hybrid covered in dark spikey hair. Depicting the murderer John Christie, his murdered female (always female) victims, and the violent act itself, Whiteley’s Christie series was first exhibited with his screenprints of beasts at the Regent Park Zoo. In forced contact with Baldessin’s twisted female forms, we are pressed to consider this undignified and graceless juxtaposition. When does affinity become cross-contamination? Is this the kind of conversation the NGV is interested in? Is this truly what needs to be said about 1960/70 Australian art?

By the end of the exhibition each of the artists is resolutely pointing to other references, in other rooms. Whiteley might be acting as bait for Baldessin, but they’re ultimately fishing in different ponds. I can imagine a satisfying contextual exhibition for both these artists that would be fascinating, flattering and useful in developing trans-national conversations about Australian art. Whiteley has three institutional exhibitions this year, so he might get a broader showing. As for Baldessin? Now that this ghostly dialogue has been established, will he get another chance to be cleaved from his a-historic graft with Brett Whiteley?

As Tillers suggests, a little grafting might be in order – we just need to find a healthier tree. Examples exist both locally and further flung: perhaps the combined Tillers/Baldessin São Paulo installation is a compelling place to start or, more ambitiously, Baldessin’s manifold international contemporaneous connections.

Victoria Perin is commencing her PhD at the University of Melbourne. Her research concerns printmaking in Melbourne during the 1960s, 70s and 80s. In 2013, she was the Gordon Darling Intern in the Australian Prints and Drawings Department at the National Gallery of Australia.

Title image: George BALDESSIN, Ultimate death of E.M., 1964, etching and aquatint, printed in black ink, from one plate, 30.2 × 45.0 cm (plate); 44.3 × 65.4 cm (sheet). National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, © The Estate of George Baldessin/Licensed by VISCOPY, Australia)