Aesthetics, Politics and Histories: The Social Context of Art

Audrey Schmidt

Over the last three days, RMIT University School of Art played host to the 2018 Art Association of Australia and New Zealand conference which was intriguingly titled Aesthetics, Politics and Histories: The Social Context of Art. Bringing together art historians, theorists, curators, critics and artists from across the region and internationally, the artworld extravaganza was centred on the premise that 'art offers a site for modelling political alternatives, questioning dominant discourses, and producing new historical narratives' through the exploration of the relationship of the arts to social life throughout history. French philosopher Jacques Rancière was referenced in 99% of the sessions I attended.

I am somewhat of a 'conference outsider' in the sense that I am not institutionally affiliated: neither with the Academy as student, researcher or lecturer; nor with museum and exhibition institutions as curator; nor even as an artist. My case is somewhat unusual. My boss and ever my supporter, Angela Conquet (Artistic Director of Dancehouse), funded my attendance in her stead via a 'development' clause in the budget, without which I would be unable to attend. Considered an essential part of academic life, but rarely considered as such in the labour force outside of academia, attending conferences is a rather inaccessible privilege—an insider affair.

As a non-student, to simply attend the AAANZ conference required a registration fee of $400 for the early-birds and $550 for the late-comers. Rather than being paid for their contributions to the conference, speakers and conveners were required to pay a marginally lesser registration fee of $300-$450 as compulsory AAANZ members (which range from an additional $60 for concessions to $150 for a general punter and $550 for 'patrons'). In some instances, generally for academics over 40 with tenure, their daddy institutions front the costs. Essentially, the majority of artists and speakers who self-fund their attendance to present papers are paying for the catering, the keynote speakers (who are paid a fee, accommodation, per diems and so forth) and for that questionable, ever-present justification for unpaid creative labour: exposure.

These costings are on par with a music festival, where, for example, general presale tickets for Rainbow Serpent are $395, except the artists don't pay, and in fact (mostly) get paid. A parallel I thought of immediately when, during the first keynote lecture, 'Settler Slut' dropped a small baggie covered in printed yellow smiley faces, containing not ecstasy or LSD but the performance enhancing eugeroic Modafinil. To my amusement, it was handed back by two well-dressed middle-aged women sitting behind her. For some reason, she said it was Valium which is perhaps more socially acceptable.

Contributing to the hedonistic festival vibe, several conference-natives pointed to a latent 'libidinal energy' at conferences. Certainly, there is a celebratory 'end-of-year' mutual back-patting for those rare labourers with a Christmas break (read: The Academy). But—libidinal? When, in his keynote lecture, Festivity and the Contemporary: Worldly Affinities in Southeast Asian Art, David Teh summoned a presentation slide that read: 'Festival and spectacle or “what are you doing after the orgy”', I could see this libidinal quality was a rather more widely felt phenomena than I had initially imagined. Personally, I can't say I had much of a 'libidinal' response to the conference environment, but everyone has their kink. Perhaps it could be compared to being findommed, a meeting of academic cashpigs, paying through their teeth for the privilege of attendance and participation.

The concept of participation is an interesting one in the conference context (particularly in one that investigates 'the social context of art'). Trends for audience/attendee participation were perhaps most noticeable during question time, which produced not questions so much as incredibly long-winded, and sometimes indecipherable, comments. Returning us to the word's Latin root commentum, meaning 'scheme, contrivance, fabrication, fiction', these comments appeared as thinly veiled attempts to be seen, heard, and a part of the conversation—a posturing. Often, although certainly not always, these comment-questions (co-quetries?) served not to further the conversation begun by speakers, but to legitimise or position themselves within the elite conference in-crowd: what Rex Butler would call a 'humble brag'. A stand-out example was during the session What Do Indigenous Art Centres Do?. Oliver Watts (Artbank), attempted to answer an attendee question by suggesting a related reading, but before he was able to name the article, the author of said article interrupted from the seating bank to say 'Yeah, I wrote that' in a particularly dismissive, almost incredulous, manner. This followed an earlier intervention where she had also interrupted National Museum curator, Margo Neale, to 'spruik' (her words) her 11am presentation the following day during the introduction to the session. Unfortunately, I didn't make the session and never caught the name of her article that Oliver Watts tried to reference. Likewise, Djon Mundine (influential Bandjalung curator, writer, artist and activist) expressed his annoyance, albeit jokingly, at not being invited to speak on the panel during question time.

An array of unintentional interventions littered the conference, particularly by way of the never-ending technical issues that ranged from bizarre live-stream feedback noises to the more commonplace computer malfunctions: Force Quit Application pop-ups, walk-outs and walk-ins and vape-like mics unknowingly held too close to speakers' mouths so that you could hear the dry-mouth clacking of their scholar tongues. Not to mention the heavy machinery and power tool sounds emanating through certain theatres due to RMIT's ongoing construction (continuously expanding beyond the 6% of Melbourne's CBD that they already own) as well as surrounding metro works. Side note: I heard a rumour that AAANZ will run at a loss this year, while RMIT siphons off a small fortune.*

However, there were also a range of intentional, although not unexpected, interventions that occurred throughout the conference as a part of the artistic program. Pre-warned to the extent that, when experiencing some unforeseen technical issues during her keynote paper (Addressing History in the Present), artist and curator of the 10th Berlin Biennale Gabi Ngcobo (who earlier joked that she had considered wearing her sunglasses at the podium) remarked with dry, jetlagged nonchalance characteristic of a globetrotter well accustomed to artworld “happenings”: 'I heard there was going to be an intervention so…'

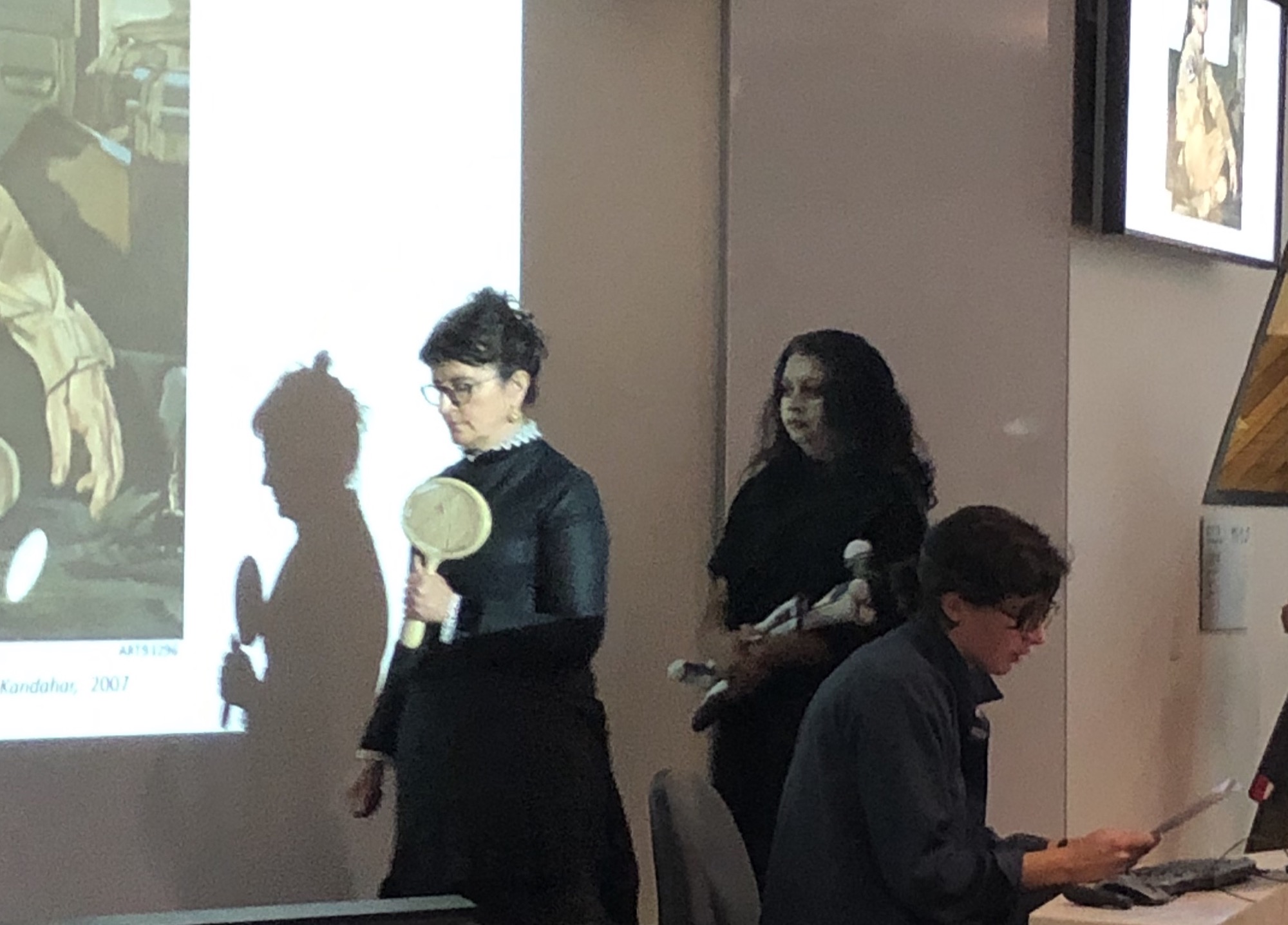

One such intervention I witnessed during two separate sessions. Two women, Maree Clarke’s daughter and Megan Evans, dressed in Victorian Gothic mourning attire slowly walking in front of PowerPoint projections, in one door and out the other, in their collaborative work with wãni LeFère. This performance titled colonise/decolonise, entailed Evans following Clarke with a hand-mirror in quiet, respectful, procession. The work was intended to 'confront the impact of colonisation' while also 'being respectful of the power relationships between coloniser, immigrant and Indigenous identities'. Subtle, almost unnoticeable when focussed on the paper being presented, the performance didn't 'disrupt' the sessions, barely soliciting a break in presenter flow, but did provide a welcome, fairly unobtrusive spectacle that allowed me the opportunity for small attention-focussing breaks—actually renewing my interest in sitting in a lecture theatre for three days straight. The proliferation of screens in many of the rooms (between 3 and 10), each reflecting the same powerpoint presentations, made for a fractured audience experience; focussed not on the speaker or a central screen but erratically hopping from one unnecessary screen to another.

Intervening on my lunch, Ben Landau appeared in hi-vis, wielding a long mop/brush where he wrote words on the pavement with water such as: 'listen', 'giving care' and 'repetitive patterns'. While the worthy intention was to question 'publics' and hierarchies of power in the conference setting, when a member of the public, also dressed in hi-vis walked through the performance looking rather confused by his supposed colleague's movements, I was reminded that this too was intended for the small art history community rather than bringing the conference themes to 'the people' or creating a dialogue between that community and 'the city'.

In the session abstract for Beyond Institutional Critique: Broader Applications of Creative Dissent, a question was posed: “how can the motivations, methodologies and tactics developed through institutional critique be applied by artists to broader social and political concerns, beyond the museum and beyond the conditions of art?” This conundrum was predominantly raised during question time, where the speakers handed out cards to attendees to write the conditions that should be considered in a prospective 'Art Strike'. What evolved from these discussions was that rather than providing a wage for artists, the problem should be considered in broader terms with the implementation of a Universal Basic Income as opposed to isolating support for artists when all labourers work under increasingly precarious conditions. One of the many vital conversations that deserves to be heard outside of the confines of an art conference.

Gabrielle de Vietri's engaging paper in this session, Social Practice of the Fossil Fuels Industry, presented a visually overwhelming mind-map of 'social value sponsorships' that sustain major Australian arts institutions—the preliminary findings of a research project conducted by A Centre for Everything in collaboration with Tori Ball and Andy Butler. A work-in-progress and certainly far too complex to neatly recap, her examples of partnerships in the performing arts were most striking as each of her PowerPoint slides playfully collaged company 'hero images' (which are always particularly spectacular in the performing arts) into visual cahoots with the fossil fuels companies that help to fund them. Opera Australia partners with ExxonMobil; Sydney Dance Company's board features a director of Woodside; mining explosives company Orica sits at the head of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra board; the board of Bell Shakespeare not only comprises a director of Woodside and Orica, but boasts Wesfarmers as a partner; Wesfarmers also graces the board of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, whose major partner is petroleum giant Total; Black Swan Theatre Company partners with Rio Tinto, Wesfarmers and Chevron as well as having connections to other major consumers of coal: FMG (iron ore) and Alcoa (aluminium). This list and Gabrielle's chosen examples comprised only one aspect of her graphcommons.com investigation that would be otherwise indecipherable without delving more deeply into the interactive map which is accessible online.

The primary purpose of a conference, which I am privileged to have my boss recognise, is surely 'development'—not just of ideas but of growth via the 'trickle-down' methodology of a meeting of minds of the cultural gatekeepers who will then ideally incorporate these learnings into their professional practice, and ultimately benefit the arts ecology and artists they support. Realistically, I would hazard a guess that more often than not, these learnings simply produce better considered theses, postdoctoral research and scholarship applications on behalf of attendees. Research that is ultimately only available to other academics and perhaps presented at the next conference to the same group of people

Talking to Gabi Ngcobo later in the conference, I remarked on the odd standardised language of academia in paper and session titles (verbing X, colon, hyper-specific noun-phrase) and she directed me to the work of MIT student, Rebecca Uchill, who made a “Random Exhibition Title Generator”. On the first click the 'curate me' prompt on the page, I was given the title: “Decadent (Im)Possibilities: The Disjunction of Sameness”.

There are other conference-isms. Awkwardly announcing the beginning and end of quotes in speeches that were clearly written for print, as a paper, without any particular consideration of its delivery (a conference staple and an expectation rather than a 'trend'). Some papers were read in their entirety painfully fast and in a monotone that made listening a much more difficult task. Others contained so much unnecessary academic jargon and blanket lists of theorists that you'd come to the end of the presentation and wonder if anything was actually said (let alone communicated). In the session What Do Indigenous Art Centres Do? an unlisted speaker, Wukun Wanambi, a Yolgnu artist from Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre in Yirrkala, Northern Territory, was essentially 'translated' into artspeak by Kade McDonald or Henry Skerritt, who recapped and rephrased any statements Wukun made with the artspeak that we somehow could not do without.

Regardless, this session was a highlight, focussing on the power of sound in an otherwise image focussed few days which is particularly relevant when considering First Nations' oral traditions. Speaker Siobhan McHugh's new podcast Heart of Artness was a takeaway worth re-investigating (or looking up if you were not in attendance) and raised the important provocation that bureaucratic “over-protectiveness” of First Nations cultures can often preclude any real constructive forms of cross-cultural engagement, not only by way of fear inducing guilt (“not my story to tell”), but also due to the perhaps overzealous administrative hoop jumping required of interested parties: a system that McHugh has had to deftly navigate in order to collect the crucial and timely (or overdue really) oral histories included in her podcast.

Further, there was an acknowledgement of the continued importance of translators and linguists in not only 'preserving' but also understanding and acknowledging the hundreds of grammatically complex Australian Aboriginal languages. As a student of linguistics several years ago, I recall that there was a trend for graduates to conduct research abroad, within already well-researched language groups, rather than in Australia.

Scrolling through the bios of the 316 presenter biographies in the 134-page document inclusive of paper abstracts, I compiled a quick taxonomy of 'interest areas' and/or professions of those listed. Of those without slashes, 12% of the speakers identified as artists, 36% academics, 7% curators and less than 1% as activists. However, as is often the case in an increasingly precarious and creativity-obsessed labour force, 42% were 'slashies'—the most popular being “artist-writers/academics” comprising 22% of the speakers.

I would really like to neatly recap Griselda Pollock's incredibly jam-packed paper The State of Art History, with Denmark in Mind…, but her captivating, expert analysis of a colossal number of complex theories that ranged anywhere from intersectional feminism to liquid modernity, make this virtually impossible. Her slides often included dozens of (sometimes her own) book titles, theorists and quotes that she had to skip over in a race against the clock. However, she ended on the note that “We might not actually have to think about (all this art stuff) 'cause planetary disaster is so close”. While she ended with a photo of a sprout emerging from the earth, as a sign of hope, I was left with the overwhelming feeling that often, as per Anna Khachiyan's Art Won't Save Us article, 'the art world's would-be revolutionaries are content to ignore…more systemic dangers'. It's not so much that these dangers were ignored in the conference's rhetoric. Quite the contrary. But from a certain perspective, even Pollock did little but rehearse and dazzlingly re-perform a century's discourse and a few extremely hot takes in the tenor of the Last Judgment—to applause and laughter that reverberated around the lecture theatre. With limited time, planetary disaster etc., the art academy's claps and chuckles have fallen silent, behind the now closed doors of this conference.

Audrey Schmidt is a writer and Melbourne Personality.

*RMIT School of Art have informed Memo Review that RMIT did not make any direct profits from the conference, and donated the academic labour of the convenors and the use of the venues. The “rumour” that “RMIT siphons off a small fortune” is completely false. The convenors would also like to note that the conference fees were the same as the 2017 AAANZ conference in Perth, and the most popular form of registration was the early-bird concession rate of $100 (which did not even cover the cost of catering over three days). In addition, Indigenous participants were offered a fee waiver to encourage inclusion.

Title image: Slide from Gabrielle de Vietri, Beyond Institutional Critique: Broader Applications of Creative Dissent. Image courtesy of A Centre for Everything and Gabrielle de Vietri (2019).)