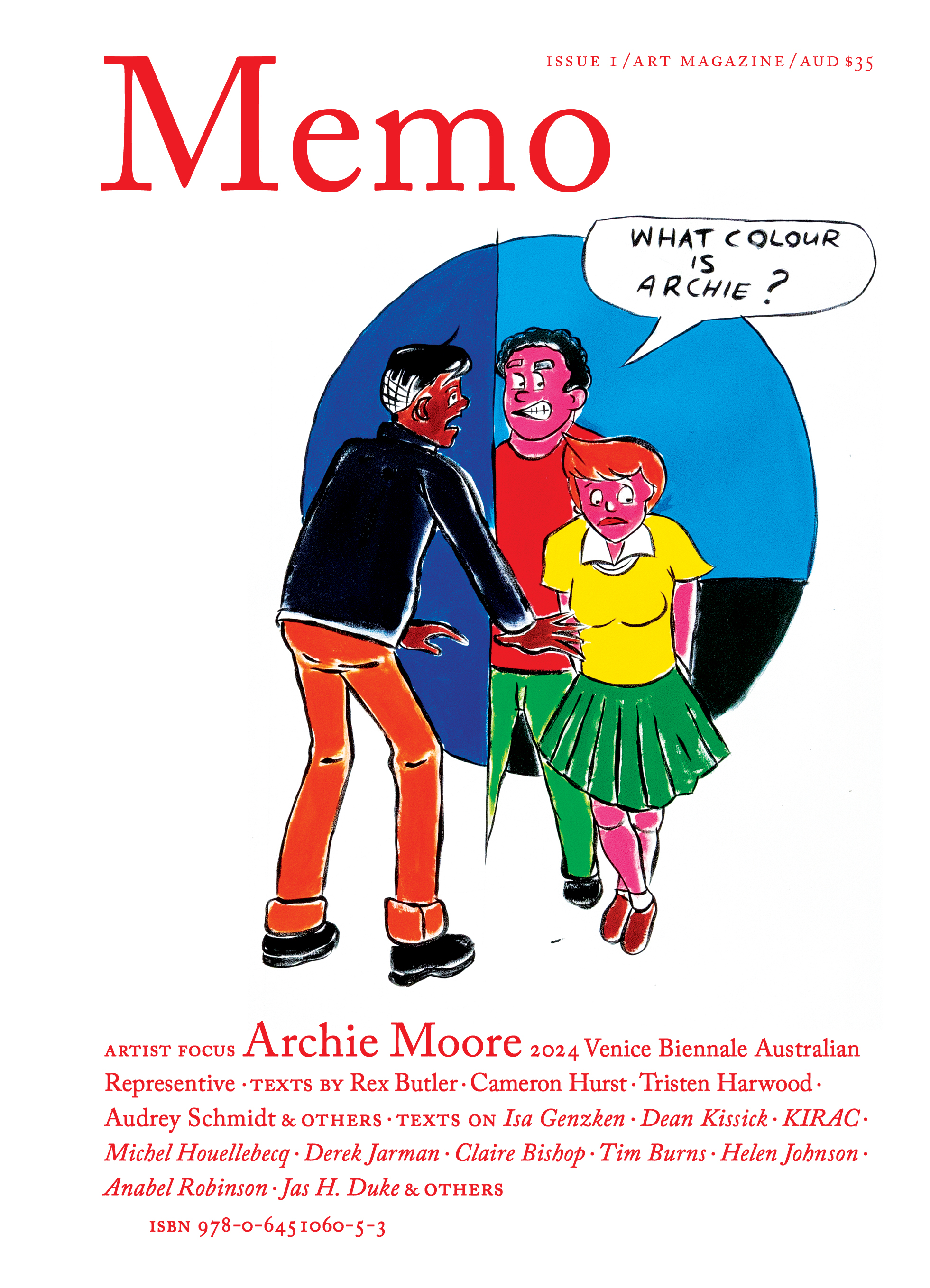

Tall Poppies

Melbourne’s art scene is fertile ground for Tall Poppy proliferation and carnage.

The vibrant poppy boasts what biogeographers call “cosmopolitan distribution.” This means they have high adaptability to a wide range of climates and the power to self-propagate around the world. For its connection to opiates, the poppy has been a symbol of death, sleep, and forgetfulness. But the metaphor of the “Tall Poppy” has political origins. It traces its history to Livy’s writings on the founding of Rome. In one episode, the last Roman king, Tarquin the Proud, wished to send a secret message to his son Sextus about how to deal with the leading men of the city of Gabbii. Instead of a written message, Tarquin walked through the garden and struck off the heads of the tallest poppies with his stick.

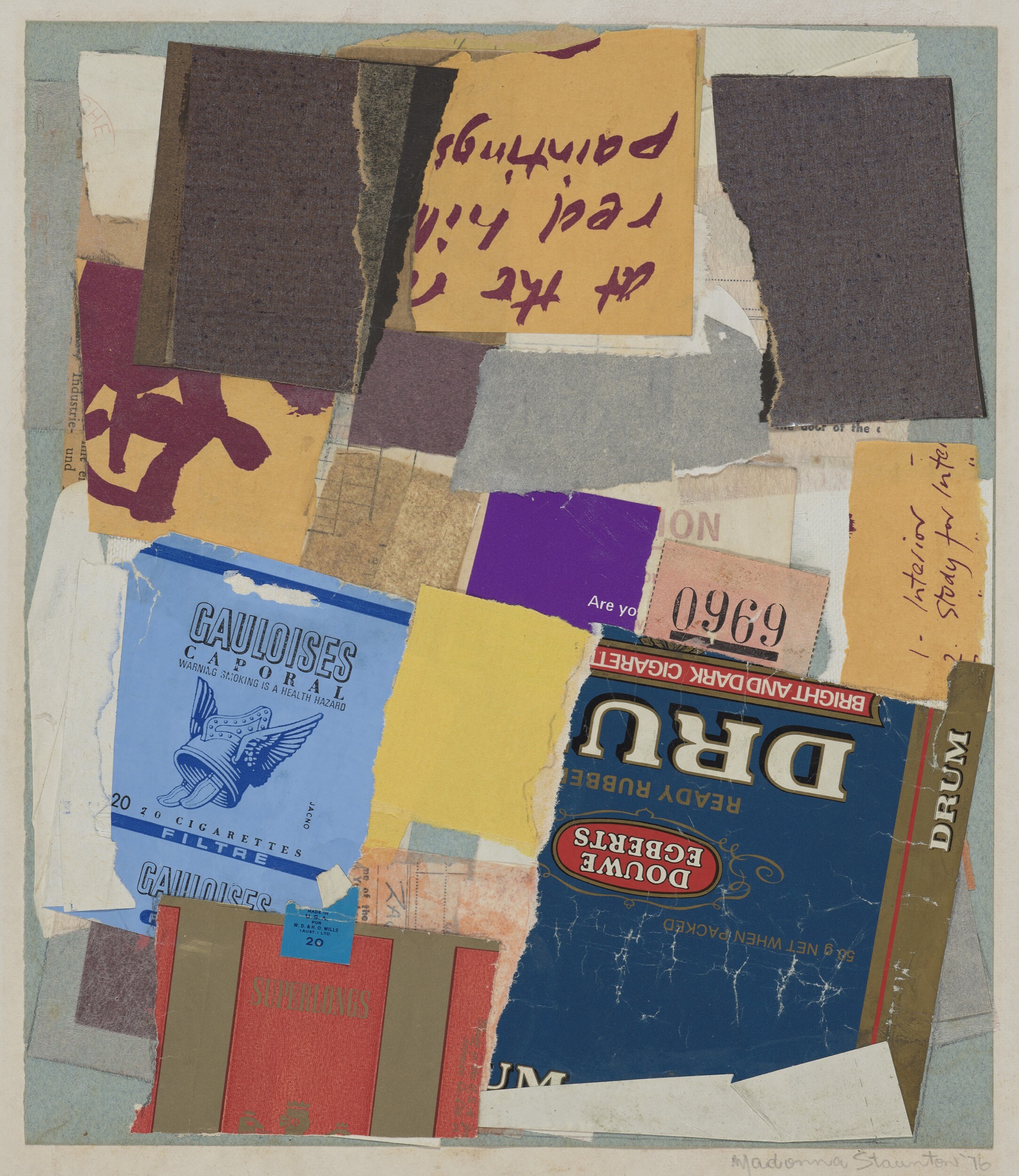

Exclusive to the Magazine

Tall Poppies by Audrey Schmidt is featured in full in Issue 1 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

By recasting Black-Eyed Sue and Sweet Poll in shackles, Sayer’s 1792 engraving subverts the sailor’s farewell to reveal convict and naval cruelty as mirror images.