Monsters of Energy

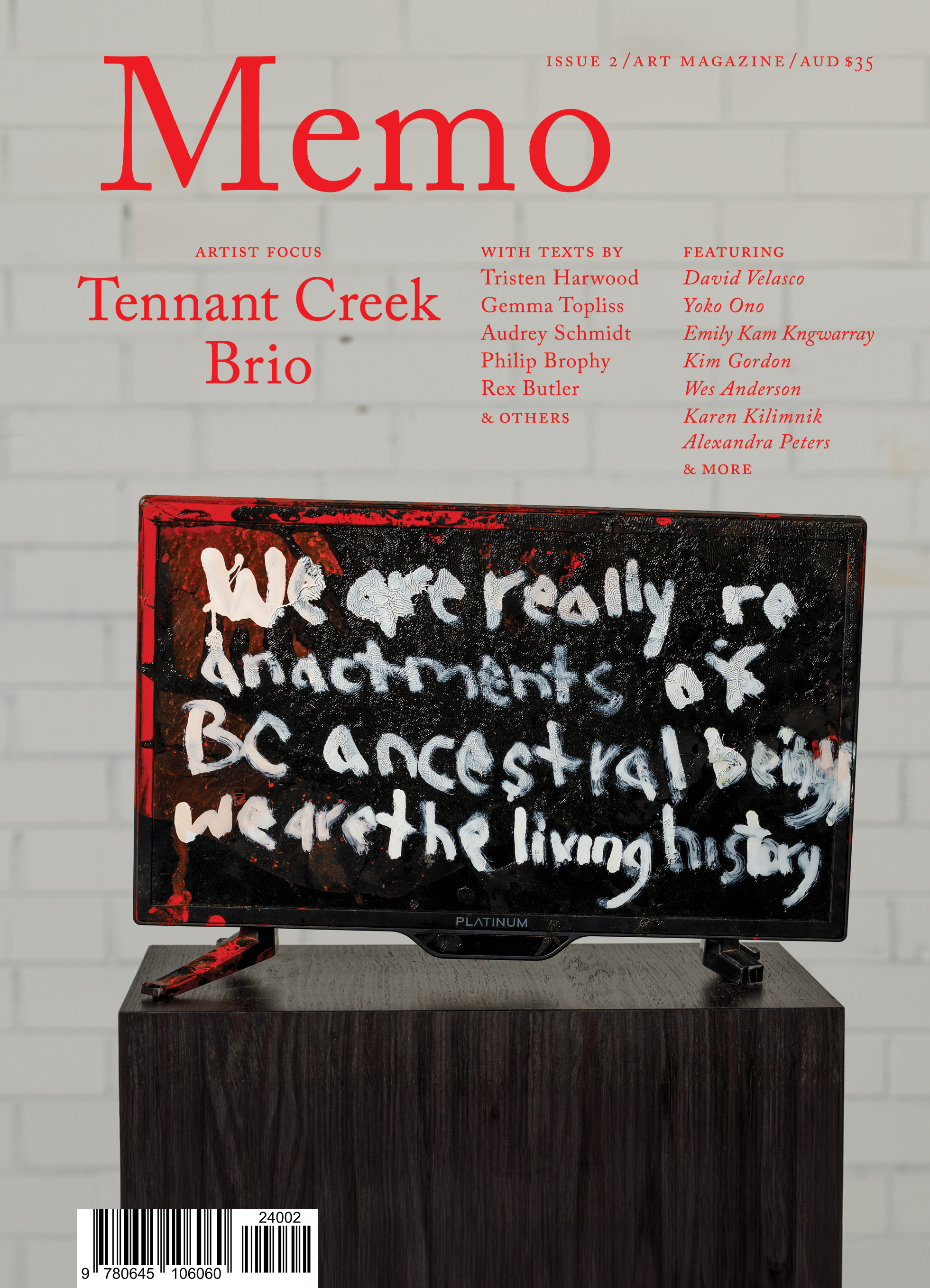

The Tennant Creek Brio’s art isn’t a legible script, a tidy lineage, or an easy metaphor—it’s a rupture, a refusal, a site of resurgence. This story sends us somewhere else, reaching for something that came before or after, looking for what’s out back, round the back of the house, the shed, the art centre, the “outback.”

Everything about him was red. His red snout, the morning red, he dreams red, the red wind, and the land is scraped stiff red by the hooves of his cattle. At dawn red. In this part of Country, the dried-out beauty is red dirt and when its heart beats — our hearts, which are mostly water, beat, because they too are coloured red. For millions of years there were no hooves, no dynamite, no excavators to scrape this land stiff. But they came and there was a red wire that splintered across the sky casting its shadow on the dirt. The world was split in two — our hearts permanently cloven.

Exclusive to the Magazine

Monsters of Energy by Tristen Harwood is featured in full in Issue 2 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

Dean Kissick’s Downward Spiral chronicled the art world’s contradictions with the breathless urgency of an end-times prophet. Now, with the column closed and the critic in semi-exile, the question lingers: was he a voice of his generation, or just another scenester burning out on his own myth?

“It is no longer my face (identification), but the face that has somehow been given to me (circumstantial possession) as stage property.” — Jason Bahbak Mohaghegh, Omnicide: Mania, Fatality, and the Future-in-Delirium

Kim Gordon grinds handrails with a Jazzmaster, vacuums in MNZ heels, and sings of capitalism’s end while modelling for its tastemakers. Object of Projection channels the aesthetics of resistance, but is it rebellion or just another symptom of “conservative cool”?