Woke in Fright

Scott Robinson

If cringe were an aesthetic, Woke in Fright would be a decent representative. The exhibition, curated by Nikki Lam and Mat Spisbah, is organised around a loose grab-bag of socio-political jargon and directed at “a myriad of dystopian functions of our absurdist society”. Ted Kotcheff’s rediscovered film Wake in Fright (1971), the adaption of Kenneth Cook’s 1961 novel, could legitimately claim to be a predecessor of the “social horror” popularised by Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). Cringe is a dominant affect in social horror. As Gregory Marks writes in his Overland tribute to Wake in Fright, horror relies on the cringe caused by being forced to “redouble (our) own damnation”. The phrase evokes Diego Ramírez’s description of the artworld in his essay accompanying the exhibition: “We are all bad people”, a “weird pyramid scheme” full of social-climbing “generic figures” who loom from positions of power to “say they will care for you”. We recognise our complicity and recoil in horror at this reflection of ourselves.

We also cringe at the self-evident, at sentimentality, disgust, boredom and sincerity. We cringe at the surplus realisation of our own sordid wishes. Cultural elites cringe at the philistinism of the masses, as does educated Sydney-born John Grant in Wake in Fright, finding himself in the outback mining town Bundanyabba (or “The Yabba”) when resident “Doc” Tydon tells Grant that “all the little devils are proud of (their) hell”. Grant’s effort to keep his head above the beer-soaked sand requires persistent disdain for the locals for whom “Discontent is the luxury of the well-to-do”. We cringe at the white male Australiana precisely as does Grant, unreflexively, yet there is an innocence to the inhabitants of this backyard dystopia.

Not fear but cringe (as Johanna Isaacson suggests in her recent book, Stepford Daughters) is horror’s dominant affect as it spits its returned repressed onto the walls of a re-branded electrical substation called The Substation. The literal retention of the name does not conceal the post-industrial loss of function, an eery void many of the works in the Woke in Fright examine. The curators explain that the exhibition “explores our ideological blindspots at a time of unprecedented circumstances” which nevertheless feel familiar, like going to Disneyland and pointing out cultural imperialism.

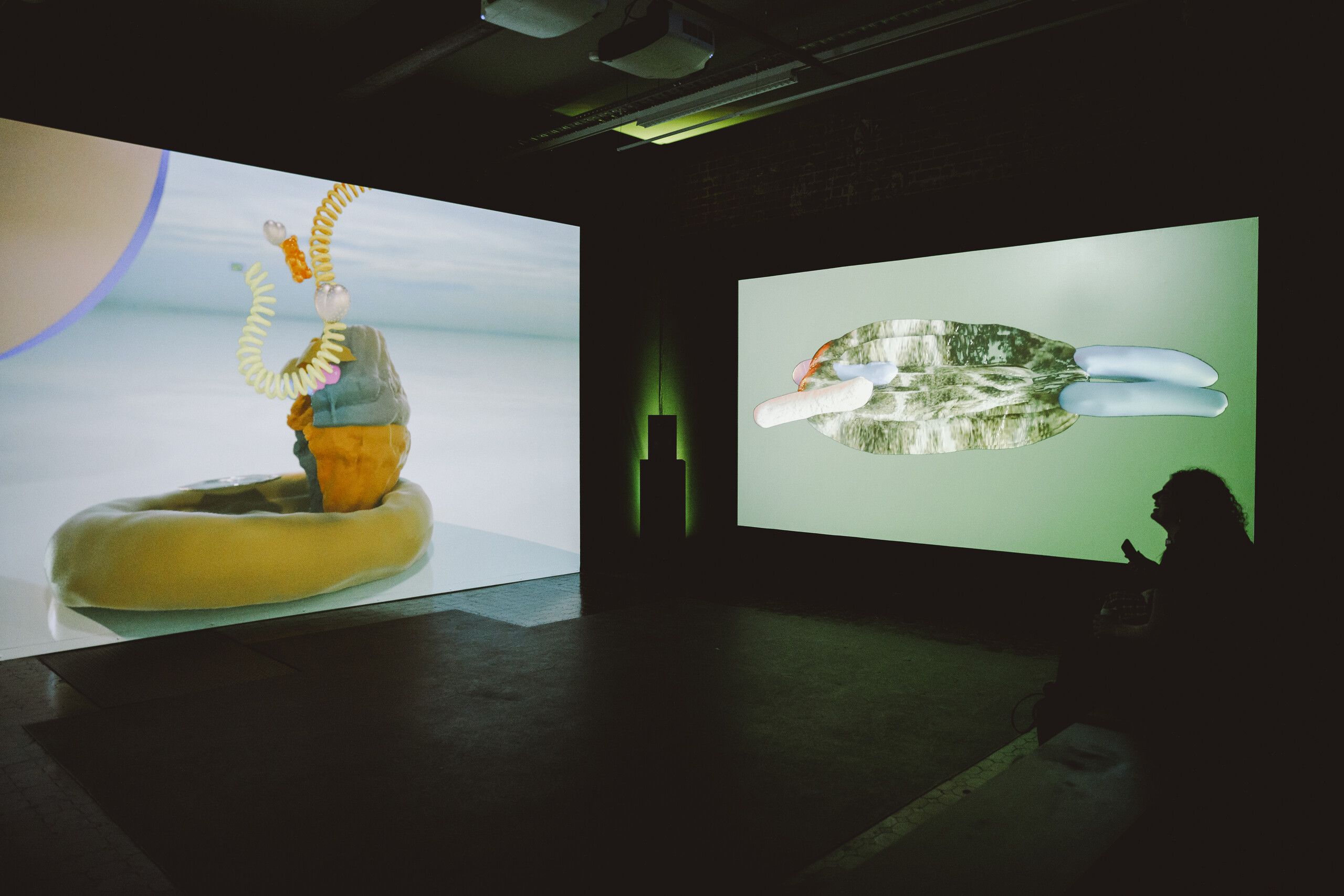

Although the works are mostly separated in darkened, exposed-brick rooms, the main space echoes a disconcerting electric buzz. Audio tracks overlap and speakers fizz with the low-fi sibilance of the audio in Li Hanwei’s Liquid Health Company (2017–ongoing). Two parts of Li’s ongoing project are displayed in the main space. The work resembles a glossy mutant of an advertisement and a low-budget Marvel movie. Characters stride through swooping shots, tracked by drones as they move through landscapes of brand-name cars, up the steps of a corporate headquarters reminiscent of the Rockefeller Centre or Chrysler Building in Manhattan.

The work directly mimics these stylistic cues, showing how the generic corporate affirmation of health and wellbeing disguises a wet-brained affirmation of accelerationist dystopia. The colourful figures invite us into the fantasy, corporate propaganda’s sickly combination of identification and envy. Their bodily movements are slick with weightless competence whose purpose is deliberately obscure; it is the mystifying choreography of obsolescence. Human desires and dreams are siphoned into instant gratification, wealth accumulation and state power. The circuit is completed by military-industrial surveillance technologies.

Li’s Liquid Health recalls the company town being designed by Alibaba, a giant Chinese conglomerate. The subtitles in the work read “Putian and Gucci’s weaknesses in conflict”, exhorting instead unity and the common dream. Putian is a city in the Fujian province where “legitimate” and “knock-off” sneaker manufacturing exist side-by-side. According to Reuters, Gucci has sued Alibaba for hosting fake apparel on its online marketplace. In response, Alibaba incentivises workshops to set up their own brands. Meanwhile, Alibaba is building “Cloud Town” at the outskirts of Hangzhou, a smart city that Alfie Bown describes as “a half-empty dystopia of almost comic proportions” in words that are apt for Liquid Health’s corporate ambitions. Liquid Health mines similar psychogeographic terrain—of the “Chinese Dream”—as Jessica Kingdon’s 2021 film Ascension. Yet the latter is a more firmly rooted representation of the uncanny combination of immiserated handcraft, Fordist production and post-industrial service work, woven together by nostalgia for archaic customs and directionless consumptive desires.

One striking scene in Ascension portrays the production of sex dolls, with workers using heating elements to melt and shape the silicon contours of gaping job-ready mouths. They smooth the seams on outer surfaces to deepen the buyer’s submission to Pygmalion’s fantasy that his Galatea comes alive (while also remaining a mute receptacle). EJ Son’s Dancing Teddy (2022) directly attends to the dynamics of the “sexual aid” with a jovial large-scale teddy bear whose swaying hips momentarily distract the viewer from the camera eyeball poking from Teddy’s innocuous furry head. Like Li’s Liquid Health, Son explores the role of surveillance in the incitement of desire. The way people interact with Dancing Teddy and its nanny-cam appendage demonstrates that surveillance is an appendage to our delight, as if the joy we derive from swaying our hips is “propped” (to use Jean Laplanche’s term) on the knowledge that we are also being observed with the inhuman vigilance of a CCTV circuit.

Like Nietzsche, who wrote that Pygmalion was “certainly not necessarily an ‘un-aesthetic’ man” because of his horny fetishism, Son is unafraid to mix the almost childishly innocent pleasure of the dance and plush warmth of the bear with self-conscious cringe. If the front of the bear is a field of desire in which entrants to the space discover their image in the Teddy’s solicitous eye, then the curtain behind suggests a classic peeping Tom scenario. The curtain proposes that what incites desire in front of the bear is supported by the implication of a concealed viewer, and in the work’s own system of charming illusions, it—knowingly—causes viewers almost automatically to start filming both Dancing Teddy and themselves. But like the tennis ball massaging the back of the bear to smooth the mechanical sway of its hips (a reference to a viral dance craze from 2020 called #zerotwodance, in which people filmed themselves pendulating in more or less pornified outfits, if the YouTube compilations are any reliable archive), the solicitation of desire is not all it seems, and the realisation of our wishes is not exactly what we imagined.

Son’s Dancing Teddy stands awkwardly in the same space allotted to April Lin 林森’s TR333 (2021), a “speculative documentary” so serious it makes one cringe. The work consists in an interview with a tree of a species concocted from a “patchwork amalgamation” of climate-resilient “hybrid forms”. TR333’s mode of communication refuses conventional environmentalism, yet aspects of the work defeat this intention. The voiceover is scrambled and requires the translation of subtitles, written in an old-timey font used by Irish pubs, or the Tolkeinesque fantasy of talking trees. It rejects its given name “Cladis Meliora”, which as Nicole M. Nepomuceno notes in Art Asia Pacific, means roughly “better disaster”. TR333 says: “I’ve been studied and dissected, but I can tell you on my own terms”. But the interview doesn’t really go anywhere and ends in moralistic anthropomorphisms like “Say hi to the next tree you see”. Lin might have discovered a cyborg-twee aesthetic appropriate to soothing speculation for the “ecocidal generational trauma”.

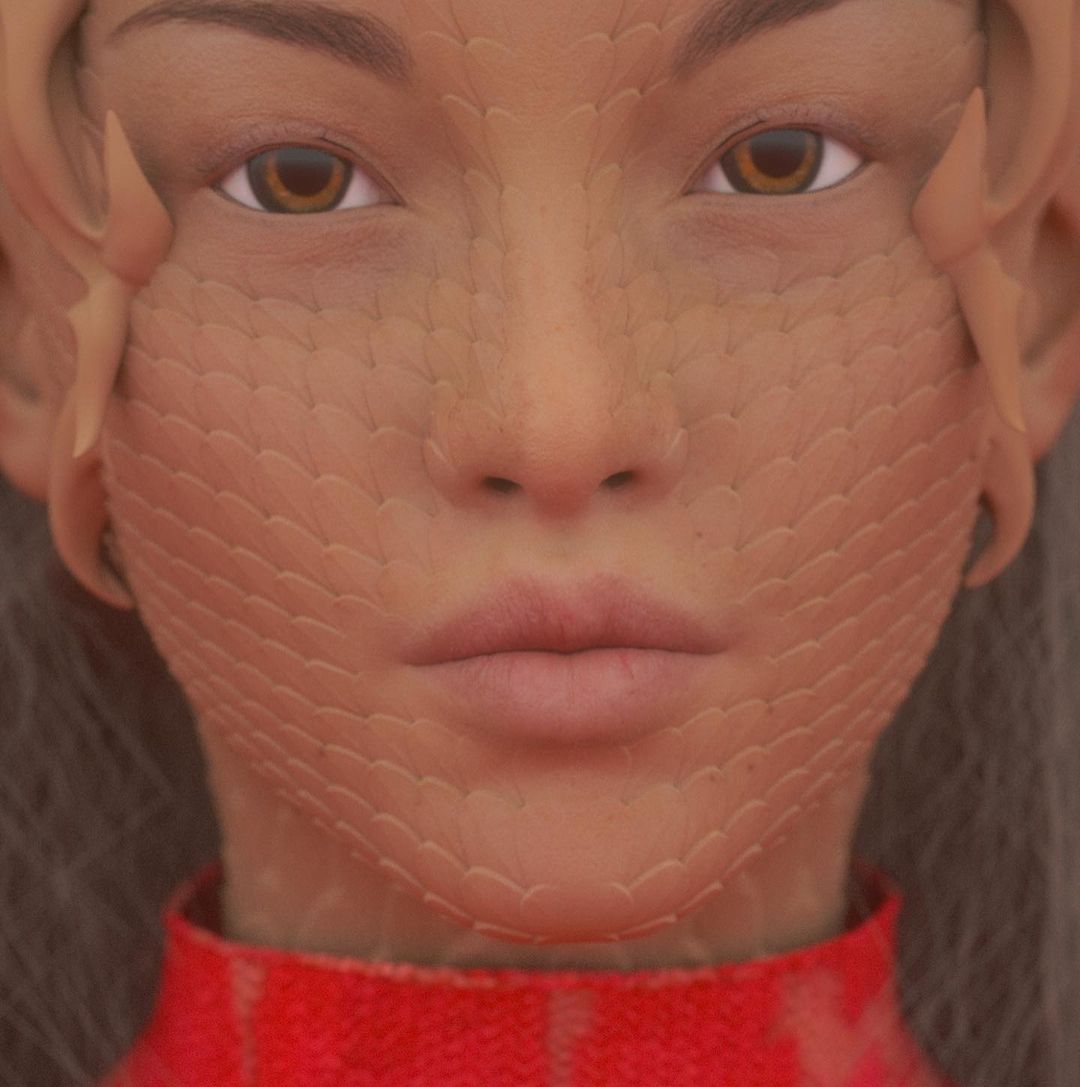

Coddled speculation might also be an apt description of Veeeky’s work Sustainable Data “STDT” (2017–ongoing), which like Li’s Liquid Health takes the form of a company that “aims to combine the culture of today’s society with new (SR1) ethics and social codes of tomorrow. This is “the product launch”, reads the description. Three HD video screens display rotating computer-generated character-like colourful blobs. The blobs could be mascots for a publicity campaign about cyber security for children, projecting a “safe” aesthetic of sustainability, pre-figuring Lin’s more ominous warning with TR333. On one screen, the blobs interact with landscape-like forms that never quite take shape. Their ever-flexible mutations might service infantile gratification in moving primary colours but they read as unsatisfactory and indecisive.

Ip Wai Lu’s Karma Cycle (2019) depicts a bored figure cycling through various exercise routines and dressed as a Qian Dan, the man who plays the female lead in Cantonese opera. Beginning with weights, the camera pans in close up over the face and robed limbs of the character, as they ritualistically, even mechanically, tone their concealed body in a gym decked out in black curtains and atmospherically wafted with smoke. At the halfway point, the figure enters a blue-glowing chamber and coyly steals a glance at the viewer before beginning the cardio portion of the workout. As they pound the treadmill, a rainbow circle spins above. The Apple spinning wheel conveys a sense of stasis, compounded by the camera’s restless panning that seems to search for a crack that doesn’t exist. The quietness and slowness of the performance, unhurried bicep curls and a lazy trot on the treadmill, belies the giant fissure of the Qian Dan. Ip’s interest in repeated movement in works such as Daily Routine: Gymnastic Exercises (2016) follows Bruce Naumann’s Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square (Square Dance) (1967–68). While Naumann stripped the gesture back in a conceptual reduction, Ip’s works tend to heighten the artifice with elaborate full-body costumes.

In this context of obsolete graphics and ritualised movements, Hannah Arendt’s comment from the ‘The Crisis of Culture’ is apt. She writes: “the power of well-worn notions and categories becomes more tyrannical as tradition loses its living force … it may even reveal its full coercive force only after its end has come and men no longer even need to rebel against it”. Woke in Fright is caught “between past and future”, with desiccated remnants of traditional cultures like masks in Li’s Liquid Health or the Qian Dan costume jutting against the futures imagined in works like Veeeky’s Sustainable Data or Lin’s TR333, which want urgently to shed the past but are caught in a decade-long glitch.

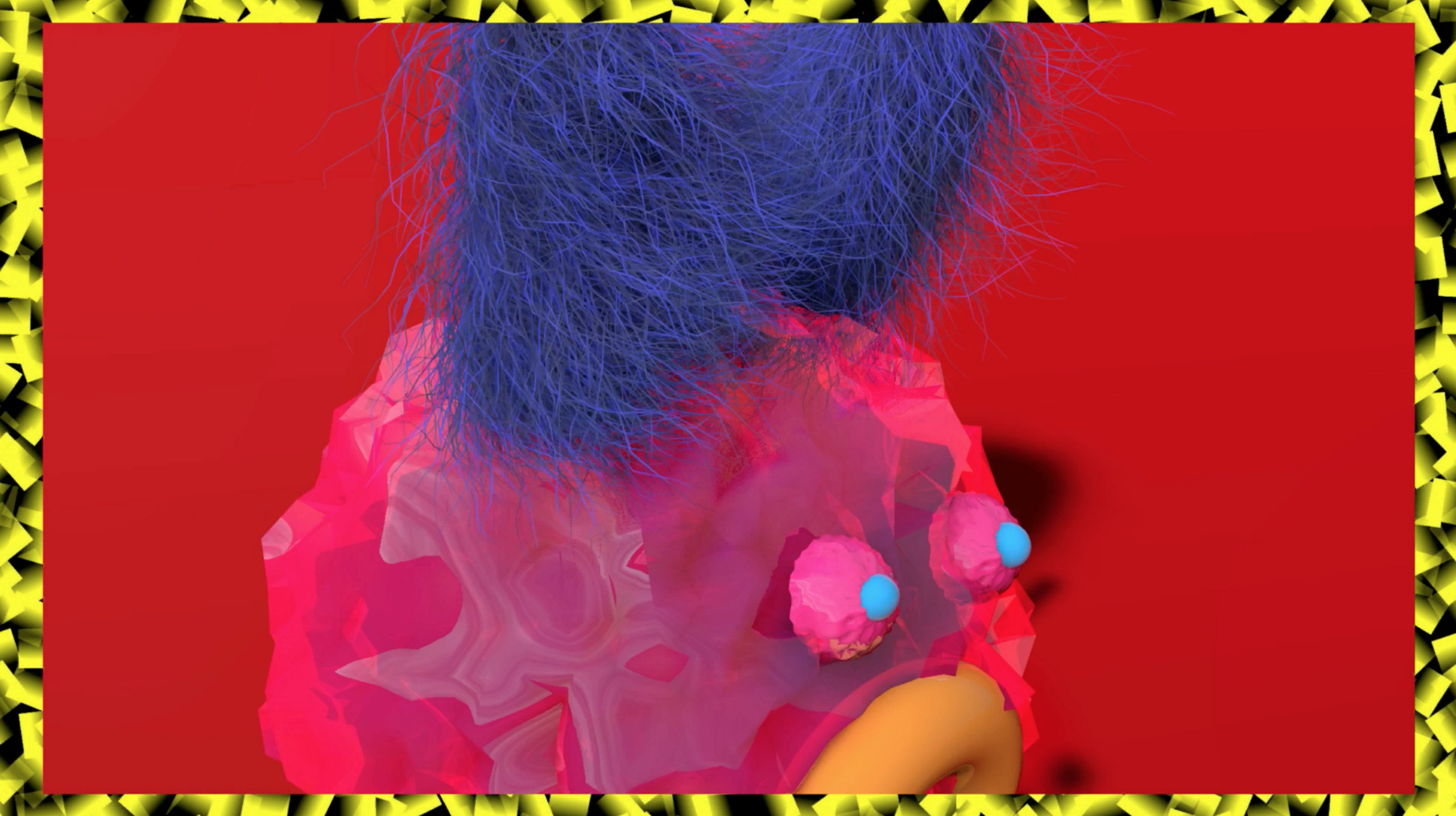

A work that wants to flash in the present is Ari Tampubolon’s Sour Candy (2022), displayed on screens split by an obscuring wall so that the two halves have to be viewed from a corner. It is accompanied by a piece of memorabilia from Lady Gaga’s Chromatic Ball tour in 2022, a sour candy lollypop repackaged as booby trap: not that deep (2022) and installed in a vitrine, like a pointless second wrapping. Unlike Félix González-Torres’s Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991), which consists of a disappearing pile of wrapped candy, Tampubolon’s preserved booby trap refutes any memorialisation, even shooting the warning “not that deep”. But Sour Candy is a sort of garish, glitter-spattered and lube-lined tunnel into the libidinal substrate of pop music and TikTok videos. To the soundtrack of Lady Gaga and BLACKPINK’s song Sour Candy (2020), the work montages celebrities, distorted faces with mouths that gape into black voids and pornographic clips.

It ends with a figure dancing to the music, shot from above in fisheye with videography by Emily Seif. But Sour Candy’s heightening of pop music’s porn-saturated palate feels like a bid to generate scandal that splutters like viral content. The work connects Gaga’s return to dance music to the political economy, suggesting that it drowns out the imminent crisis in an aphasia of thumping rhythm. But Sour Candy is neither a materialist excavation of pop nor a psychic exploration of its unconscious. Rather, it expands range of reference to celebrity memes outward into the digestible flow of the “entertainment industry(’s) gargantuan appetite” for content. Artistic appropriations of Lady Gaga are over-saturated with Stefani Germanotta’s first-year art school interest in Andy Warhol and ambition to have “an installation at the Louvre and MoMa”. The work reads like a disappointing orgasm, filled with unwanted fantasies from the detritus of eyes over-exposed to the internet, piling rather than digging on the surface of TikTok banality.

Digging into the industrial production line behind the song Sour Candy reveals a rich seam in cringe aesthetics. Song-writer Madison Love cites as inspiration an ad for Sour Patch Kids. Further investigation uncovers a fifteen-second spot in which a young Girl/Woman wakes up to discover that one of her preposterously upright pigtails has been severed by a child-sized sour gummy bear. The bear guiltily drops a large pair of scissors and then hugs the pyjama-clad pseudo-adolescent before a slogan reads, “Sour. Sweet. Gone”. The song barely needs to heighten the creepy horror contained in the slogan. Gaga sings: “I’m super psycho, make you crazy when I turn the lights low”. Despite suggesting arousal (“come come unwrap me”), the song barely conceals a threat of violence (“if you see inside”). Sour Candy brandishes these associations with the subtlety of a sour gummy bear wielding a pair of scissors. Like Liquid Health, Sustainable Data and TR333, the work is soaked in the world it cites, soggy as wet paper.

Woke in Fright falters in the unadulterated reproduction of the basic features of contemporary capitalism. The show’s works are exposed to the digestive apparatus of the pop-culture industry, which does everything (multi-media companies like Liquid Health and Sustainable Data), all at once (multi-screen, multi-species conglomerations, multi-category descriptions), over and over again (Karma Cycle and Dancing Teddy’s repetitive gyrations), with just enough imperfection to keep us gossiping. The works that succeed do not so much screen existing desires, whether present or predictive, as show how boring it can be to be their object, as in Karma Cycle, or that desire requires the thrilling suggestion of an unknown other, disguised behind the curtain in Dancing Teddy.

Wake in Fright subtly presents patrician cringe at parochial mores. Despite being part of the Neighbourhood Contemporary Arts Festival, Woke in Fright drowns in the immensity of the global ambition of many of its works, caught between over-promising and under-delivering, between endlessly ongoing works and works that cannot go fast enough. The best works stall and fixate, like Karma Cycle and Dancing Teddy. They plant an idea and allow us to see it through, neither falling for pop’s absence of nuance nor cringe’s propensity for too much. They resist the temptation to liquify these disturbing, cringing fixations back into the banal flow of TikTok dances and sustainability rhetoric, which results in nothing but whipping out our phones and joining the frenzy of childish satisfaction at the cost of liberation.

Scott Robinson is a casual academic, writer and unionist whose work appears in Overland, Arena, MeMo and elsewhere.