Olana Janfa, What Is Your Gov'ment Name; Mirror: New Forms in Photography

Giles Fielke

Prolific creators. Makers. Designers. Producers of Kulchur. The Culture (RIP). Arts and Culture (Google). The rebranding of artists and artwork, and the atomisation of this significant social role into corporate grist for the mill has reached new heights in the 2020s. Just why there is so much anxiety about calling an artist an artist might be explained, of course, by the unabated continuation of violent industrialisation over the past two centuries. That is, I agree that making—the production of things by people—is art. It is also work. These creations can proliferate, but the institutional and legitimating role played by the state in this development often goes unexamined. What art does for the state, in return for its support, ties together two otherwise unrelated exhibitions currently on display at our public institutions: Olana Janfa’s What Is Your Gov’ment Name at the Immigration Museum (part of Museums Victoria) and Mirror: New Views on Photography at the State Library’s Victoria Gallery.

Consider this description of the Culture Makers program supporting the exhibition of works by Janfa, a Melbourne-based, Ethiopian-Norwegian artist:

Culture Makers is a new initiative, guided by an independent Creative Advisory Panel, in which Museums Victoria invites creative “Culture Makers” to create experiences and programs that engage and connect public audiences with our museums and spaces.

Presented in partnership with Scanlon Foundation, the Culture Makers program aims to advance participation, diversity and belonging, with seven creatives chosen for Season One to share their inspired art and programming across all three Museums Victoria sites: Immigration Museum, Scienceworks and Melbourne Museum.

Public-private bureaucratic language aside, the palpable hesitancy to call Janfa an artist—he is at first referred to as a “rising-star,” eventually an artist—seems strained here to the point of absurdity. The obvious question to ask is, “Why?”

Janfa describes himself as an Ethiopian-Norwegian artist. “Art is my way to express all that life presents: inequity, connection, intolerance, humour, exclusion, acceptance—all of it,” he explains in his statement for the current exhibition. A spokesperson for Museums Victoria frames the exhibition somewhat differently: “The values of culture makers are inclusivity, visibility, collaboration, change, and reciprocity.” So which is it? Is it the gov’ment or the artist who gets to decide on the way the work is understood?

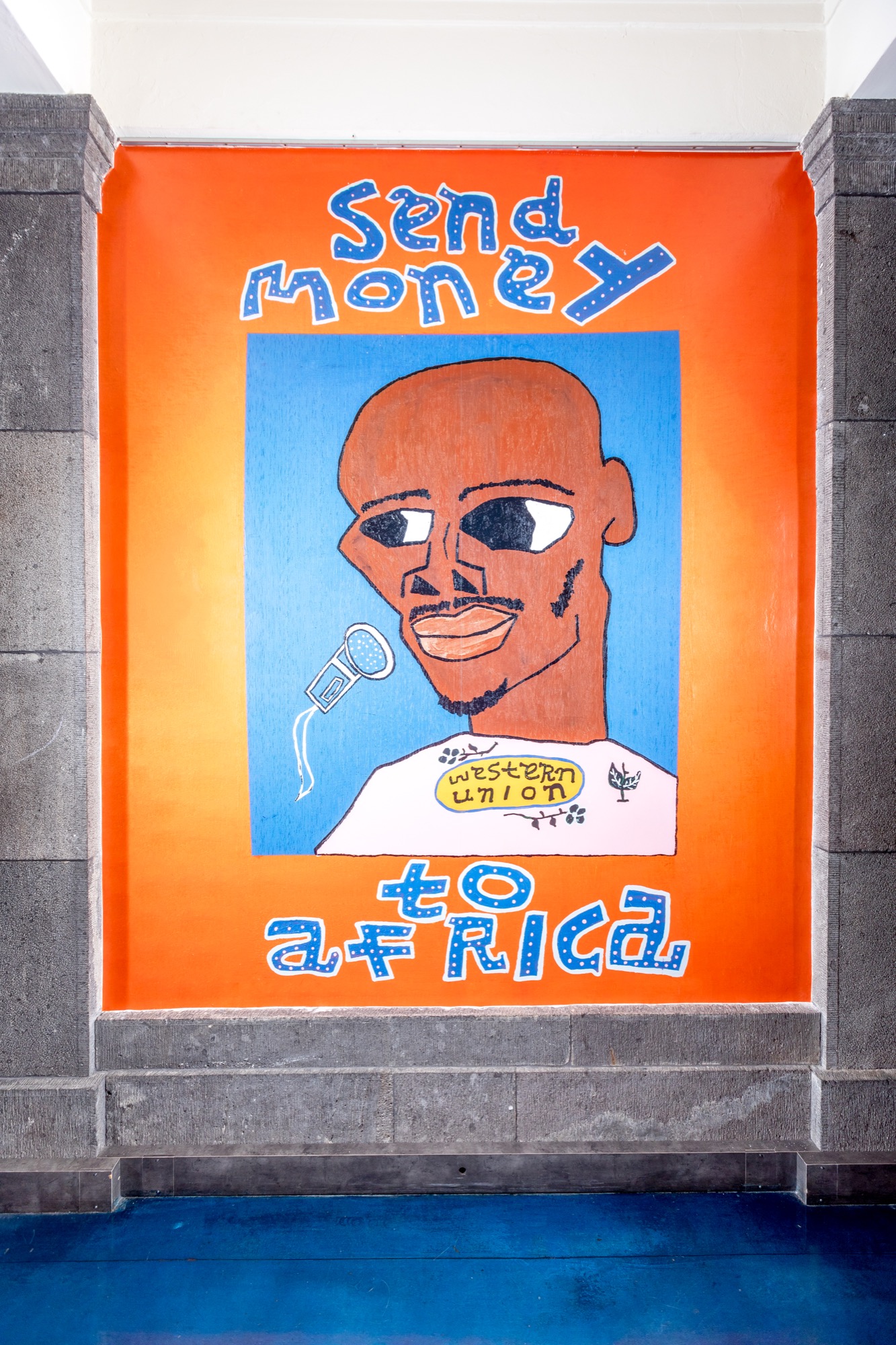

Janfa’s display is immediately accessible throughout the ground floor of the Immigration Museum—the former Customs House is a nineteenth-century Palazzo-style gold-rush building on Flinders Street—in the form of large paper-print posters of his paintings pasted onto the interior walls of the foyer. These vibrant works soon give way to vibrant postcards, t-shirts, decals, and fridge magnets (we must exit through the gift shop, of course, which is here in fact the reception for the museum).

Apart from the exhibition of reproductions of his work, it is the title of the show that is its most compelling feature. What Is Your Gov’ment Name, sans the question mark that usually punctuates an interrogative clause, inaugurates the canny performativity of Janfa’s recent imagery for the public. Referring to the idea of official documentation, what is your “real” name, the phrase instead suggests the playful ignorance of a “Where am I?” moment. I understand it to refer to—maybe by stretching the language game—the disorienting effects of migration and statelessness. In one work this title appears as the bottom text of a naïvely styled and direct painting of a police officer in a green uniform, on a pink and sky-blue geometric ground. The background colours are also used for the work’s painted text. The interrogative (and declarative) phrase therefore makes the expression painted on the policeman’s face into the question mark directed to whom he has addressed his gaze: us, the visitor.

Janfa’s work has recently been featured by global brands like Nike, despite his only picking up a paintbrush for the first time in 2018. His commission to decorate Atherton Gardens’s basketball court in his signature style also drawing inspiration from the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church he remembers from his childhood in Addis Ababa, his art is figured here as a way to bring the sport luxe and activewear behemoth into a direct encounter with a public housing project in Fitzroy. As an interesting aside, the Christian Church in Ethiopia dates back to the same year the Roman Emperor Constantine I declared the city of Constantinople the capital of the empire, in 330, after embracing Christianity himself.

It is perhaps the nascent energy of Janfa’s art that explains why work by the self-taught artist, full of hope, joy, and reality, is more often framed as culture rather than art. Unlike the late Antonio Suguí, to which Janfa’s work might be productively compared, these works all carry witty slogans that also operate as their titles. The acrylic, oil, and found materials that are the technical supports for his artwork, here remediated to (temporary) paper past-ups on the foyer walls operate in a way that mirrors his work at the Atherton Gardens Estate; they invite the public to the museum as the producer of the ideal public (as opposed to the ideal activewear consumer). Even so, the paintings here appear duly ironized to the point that they seem to openly poke fun at our expectations of the new migrant: present yourself to the local government administration. “Send money to Africa.”

In this way, there is a slippage that exposes the tension between migrant and citizen. As the Immigration Museum itself seeks to remind us: we (most of us) are not native to this country. I was genuinely shocked when I read Vincent Namatjira’s recent children’s book publication, about his great grandfather Albert, where he notes that the famous artist was the first Indigenous person from the Northern Territory to be granted full voting-rights citizenship in Australia. It is extraordinary. If I’d heard it before it certainly hadn’t registered the first time. This was in 1957, eight years after the introduction of Australian citizenship. It certainly helps my narrative, however, that is it is through art that the state realises itself. Prove your worth, show us your tricks, and we’ll invite you to the privilege party. Come meet the Queen. The echoes of Howard’s “we will decide who comes to this country” speech during the Tampa affair in 2001 seem also to be echoed throughout the halls of the museum.

Any cursory glance at how the administration of the country has been going lately—at a headline, or over the radio perhaps—might give someone new to this place the sense that things are “not great”: at present we are a country with a government that secretly agrees to use algorithms they barely comprehend to make up false debts that we’ll then use to repossess your things or kill you. And this is only in the past week.

The point is, I was prompted to further consider the links between our state art institutions and the ideological line on immigration into Australia, AC (after COVID) in the work on display by Janfa and others. But in the context of how artists might assimilate to the modes of production required by the state, it is easy to forget the message of settler inclusion. And while this year’s major debate is focussed on the looming Voice to Parliament referendum (Sky News has just dedicated an entire “news” channel to the “debate”), and the climax of the Reconciliation Australia project which was founded in the Howard era but has its origins in the Hawke-Keating era, the other side—or mirror—of this project is of course non-Native people who have come to take up residence, to work and to conduct their business, in so-called (post-colonial) Australia.

Naveed Farro’s The Pool, which ended on 25 June, included three works in the Immigration Museum’s upstairs galleries: a sculpture, video, and VR. Supported by the City of Melbourne, Regional Arts Victoria, and Creative Victoria, with development by Farro and Museums Victoria, the exhibition centred the Iranian diaspora in Australia. The inaccessible yet celestial muqarnas of the vaulted entrance to the Shah Mosque in Isfahan were contrasted with the harsh (virtual) reality of a phantom ride in a Uber Pool through Fitzroy North, just up the road from the Atherton Gardens Estate. In combination with Janfa’s series of blocky, flat, sign-paintings, the overbearing reality of the public-private model for the arts fills me with dread. The combination of references and supporting partners is dizzying. State art is back, but it has been Uber-fied.

This leads me to my next stop, the recently opened Mirror: New Views on Photography at the State Library’s Victoria Gallery. Including 141 images from the library’s photography collection co-curated by Jade Hadfield, Kate Rhodes, and Linda Short. From the outset the exhibition seems to be deliberately disorienting. Of course, the curatorial logic must be the invitation to ask the same question implied above: where am I? Curiously, none of the actual prints in the library’s collection are on display; rather, they have all been photographed or digitally scanned, and sometimes staged as BTS shots in the archives of the neo-classical building. Then they are projected in the two opposing “cinemas” built into the gallery, and onto the opposing walls are video works reflecting on the set of images. The result is a narrativization of the selection which to me had no identifiable logic other than “these are nice” photos. Instead of artwork, and artists, the heavy-handed exhibition design takes centre stage—formal interventions and plush seating seem to suggest the budget for the show was rather spent on the production design, and media surrounding the work, as opposed to the work itself.

Seven decades of photos are on display. Mid-century works by Wolfgang Sievers and Helmut Newton; 90s snaps by Destiny Deacon, Viva Gibb, and Ross Bird; a random photo of Olivia Newton-John on the cusp of celebrity in 1963, aged fourteen or fifteen. All act as prompts for an immeasurable amount of canned commentary, activating the archive, and disallowing the viewer to simply negotiate their own encounter with the images. This seems to be indicative of another way that the anxiety over artmaking, of the possession of these works, is manifesting in the collection. Symptomatic of a larger problem often faced by contemporary art, the foregrounding of curation and exhibition design, the selected images are wrapped so tightly by the criss-cross of supplementary commissions means everything has been pre-determined. Piped around the gallery were words and songs by Victorian writers such as Alice Skye and poet Prithvi Varatharajan; the hosts of the Triple R radio show Superfluity discussing the “selfie” by Sue Ford from 1961. Yet what has been decided about the works remains unclear. I couldn’t wait for the Pasifika Storytellers Collective, there is no information about when or how long the video works will play for. Neither was the visual essay by Leah Jing McIntosh, in the form of a giant rearranging grid of the photos, and a narrative arrangement of sorts, discernible from the slide show of images showing simultaneously in the cinemas. It is a lot.

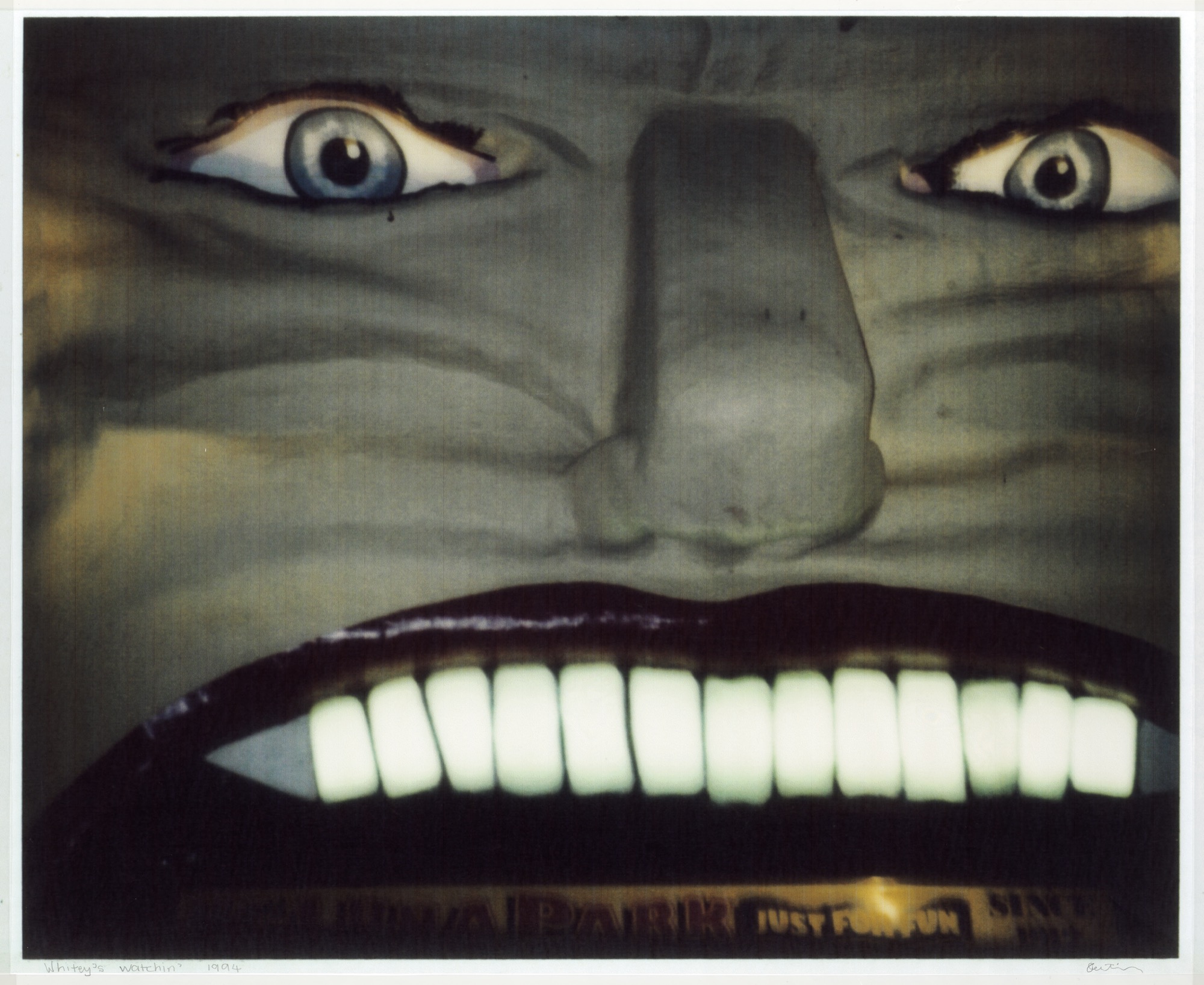

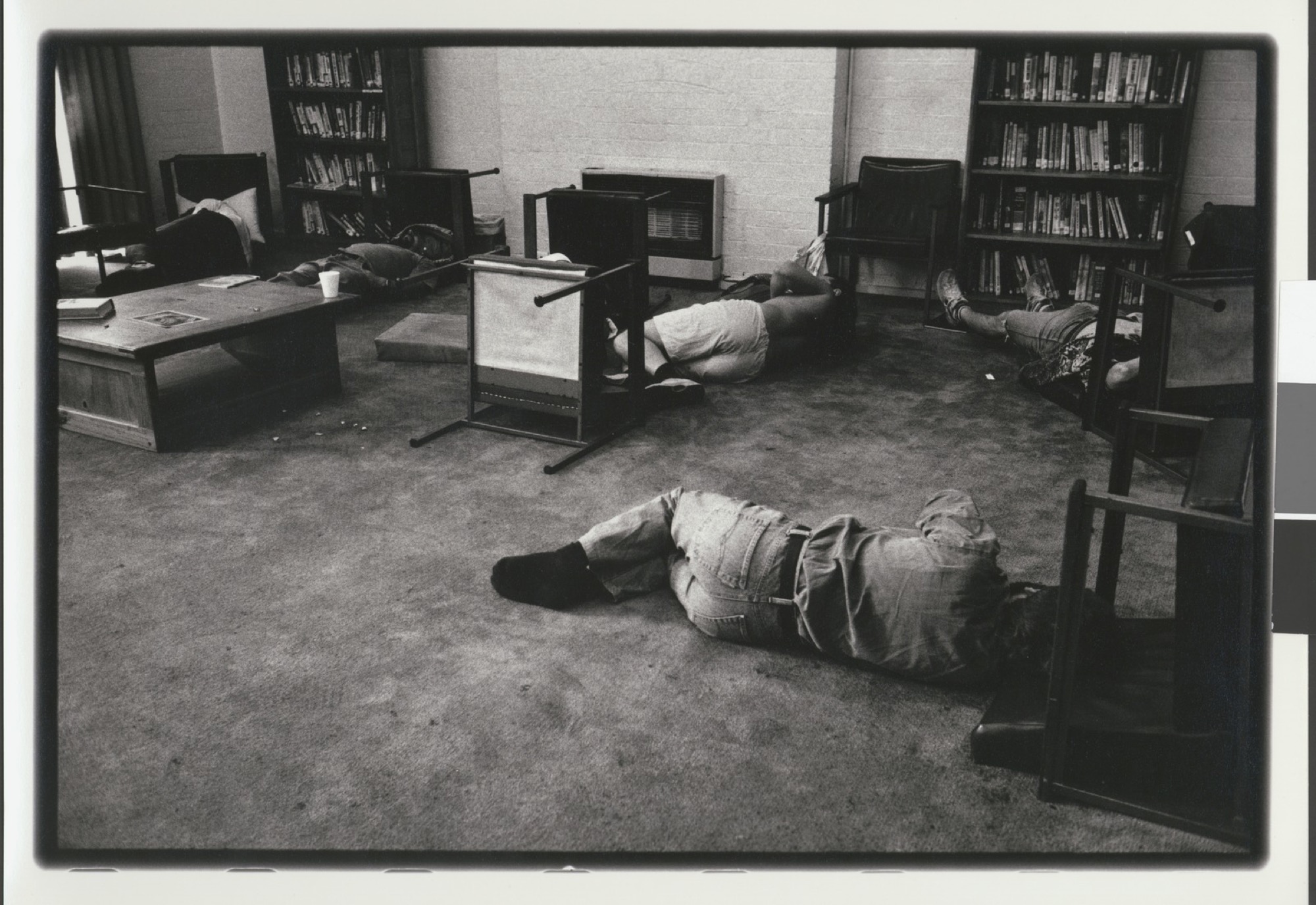

What’s more, the accompanying curatorial statement soon becomes an apologia: “not all Victorians will see pictures relatable to themselves or their families or cultures.” Is the state gaslighting me? “Not everyone in the photographs is named.” Some of the best work selected doesn’t even feature people, such as the scan of Deacon’s bubblejet printed photo of Luna Park, Whitey’s Watchin’ (1994), or Mark Strizic’s colour slide of a pair of eighteenth century silver sweetmeat dishes from the 1970s or 80s. The curatorial statement then concludes that “the images represent historical institutional blind spots and biases that we are working to correct, and this exhibition is part of a process of reckoning.” A Mathias Heng work shows the prostrate bodies of six people on the floor of the Gill Memorial Home on A’Beckett Street, in a devastating black and white gelatin silver print from series shot in 1995. Projected, the images appear forensic, like evidence of a crime scene. It becomes clear why the apology has been foregrounded. By focussing on representation, it’s as if the curators have forgotten about the work of art, its ability to produce something, seemingly out of nothing.

The respondents and creative collaborators listed under the names of the photographers, bathed in the warm light of the “lobbies,” oppose the infantilising language of the exhibition layout: “You might be here … Maybe you are here. You can sit here.” All of this combines to make the whole experience of the show uncomfortable, by employing the formalist notion of “estranging” these objects, the modernist approach to display is jarring against the actual contents of the works. But there is an easy remedy for this, dear reader, I’d recommend perusing the selected images on the library’s collection catalogue (only 135 are available). That is, unless you are intrigued enough to want to attempt to understand the alienating installation of the exhibition. The state can’t distance itself, from itself, can it?

This week green-washing hit the headlines when the ACCC published draft guidelines for improving environmental integrity following an “internet sweep” in March, our corporate-critical vernacular blown up by the federal regulator. But what about diversity-washing? It takes me no time to find an academic article on the topic published late last year by the Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research. Perhaps the moment has already passed. The Scanlon Foundation, supporting the Culture Makers program is a twenty-first century philanthropic organisation named for a local billionaire businessman, and dedicated to social cohesion and migration. Is it possible that the sublimation of the artist into this matrix, instead of being a cynical move, is perhaps a good thing? If art is also a presentation, not just representation, then its dissemination throughout all forms of contemporary cultural production aims to reveal the state to itself. It feels too optimistic to say this, but maybe that is the truth? All art is aimed at the state. Yet poetry, as representation or imitation, necessarily leads us away from the world.

In the dematerialisation of the works, this covering over of the truth, I was reminded of the poetry of our most iconic robber-baron, Gina Rinehart, immortalised on bronze plaque affixed to a “poetry rock,” a hunk of iron in Morley, WA. It’s cited by Sam Beard in this week’s Dispatch Review, considering the state of public art in the west of the country:

The world’s poor need our resources: do not leave them to their fate/

Our nation needs special economic zones and wiser government, before it is too late.

Originally, I was going to use today’s review to gather some musings on the slowly unfolding event that is the Melbourne Art Precinct, or MAPCo project, a corporation established to deliver “Australia’s largest ever cultural infrastructure project.” This is the scale at which the state institutions for art are made. But I quickly realised there isn’t really anything to write about yet, let alone to see (except construction sites and branded hoardings) adjacent to the ABC building on Sturt Street. But now I imagine the precinct is like a terraforming layer over the entire city, a shroud perhaps (a map). What does it cover? What is your gov’ment name. It is the interrogative clause that gets me because I don’t think I can answer it. I don’t think I can name the people who are in charge anymore.

Giles Fielke is an editor of Memo Review.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of Meridian Sculpture.