Wayne Eager New Paintings

Ian McLean

An exhibition that caught my eye last week reminded me that the surrealists didn't seek their aesthetic thrills in Paris' modish contemporary art galleries or amongst the Old Masters in the Louvre, but in unexpected places. Somewhat off the beaten track, in an old picture framer founded in 1879, about a dozen very uncontemporary large abstract expressionist paintings occupied an adjoining exhibition room with surprising authority and autonomy. Here was an artist in full control of his materials but with nowhere to go.

Knowing the artist from long ago as someone who always trusted his sensibility no matter what the artworld threw up, I realised he only had himself to blame for this fate. Now in his 60s, Eager will not be rewarded with a state art gallery retrospective that artists of stature can now expect in their later years. He is not represented by even one work at the NGV. His fate, though, is not that of most artists, which is to remain invisible to the artworld. Eager has enjoyed moderate success but his career peaked early, in the mid-1980s, long enough ago to have been dragged into anonymity by a certain entropy that once it takes hold is rarely reversed. Anyway, the peak was not that high: he never enjoyed institutional patronage except for a brief moment from James Mollison at the National Gallery of Australia. He is best known as a member of the founding group of young so-called expressionists who established Roar Studios in Brunswick Street in 1982 and disbanded in 1983. But by then it was already over. Despite a small skirmish, now long forgotten, Eager and his mates at Roar Studios were no match for the theoretical and institutional firepower of Postmodernism.

Most of all, Eager's timing was off. The end was already nigh when he was still learning to walk, as the thrill of advertising imagery swung a new generation of artists from the existential wrestle with the plasticity of paint to the seduction of the image. There was definitely no going back after The Turning, which the world remembers as '1968' but Melbourne remembers as The Field. This art exhibition so divided the Melbourne art world that it nearly spelled the end of the Melbourne Style.

From Withers to Williams the main subject of the Melbourne Style was the unifying role of light in landscape, from which was forged a sensibility that suited the national ethos – but an ethos which by 1968 was on its last legs. The idea of the Melbourne Style is my own dubious generalisation to open a door onto Eager's fate. A few broad brushstrokes would place its origins in the late nineteenth century amongst artists who kept one eye on the Paris Style but the other more firmly on the plastic values of paint and tone. From the beginning, it was a broad church (its early parishioners ranged from Streeton to Ramsay), sustained in all its differences and bitter disputes by an unquestioned faith in the truth of painting, a moral position that gave it a sense of comfort and satisfaction. This comfortableness, also evident in Eager's paintings, is what gives the Melbourne Style its distinctive regionalism. Its practitioners fought amongst themselves but not the world, as if Melbourne was the world.

The Melbourne Style survived '1968' by shifting its subject to global media images but retaining its core belief in the plastic values of paint. Eager's art school lecturer Gareth Sansom – who currently has a retrospective at the NGV – showed how this could be done with some panache, but the lesson didn't rub off on Eager who, except for the music, hardly seemed to notice the 1960s let alone the 1970s.

Some claimed that Roar Studios revived the old Melbourne Style, but if this was the case the post-1968 taboo against it, fully institutionalised by the 1980s, was too strong. Nevertheless, the values of the old Melbourne Style live on in worlds away from the artworld, in out of the way places and in the regions where the virus of postmodernism never took hold. In Alice Springs, where Eager has lived for some 25 years, he is well known and he even has a small following amongst some Melbourne collectors.

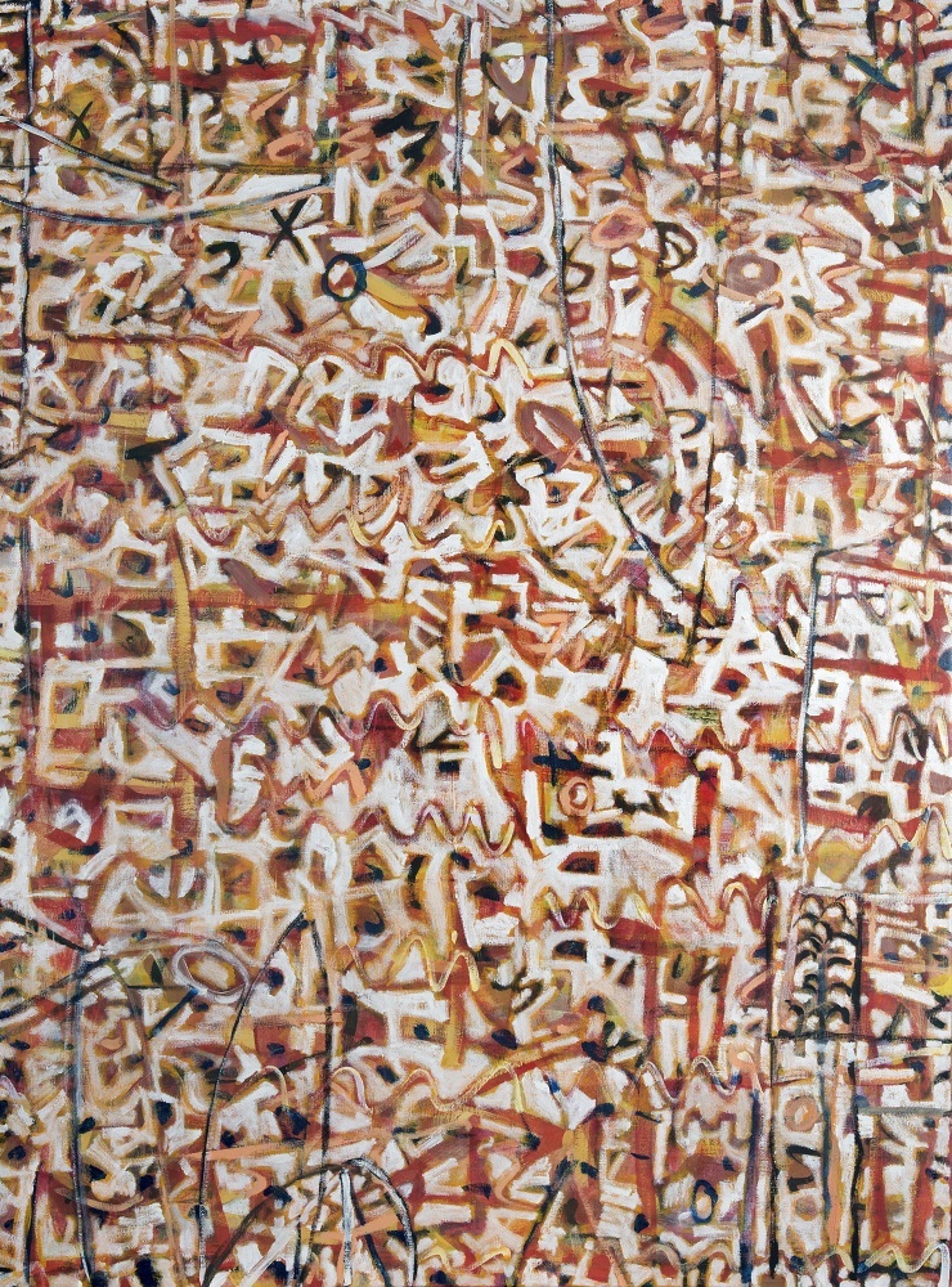

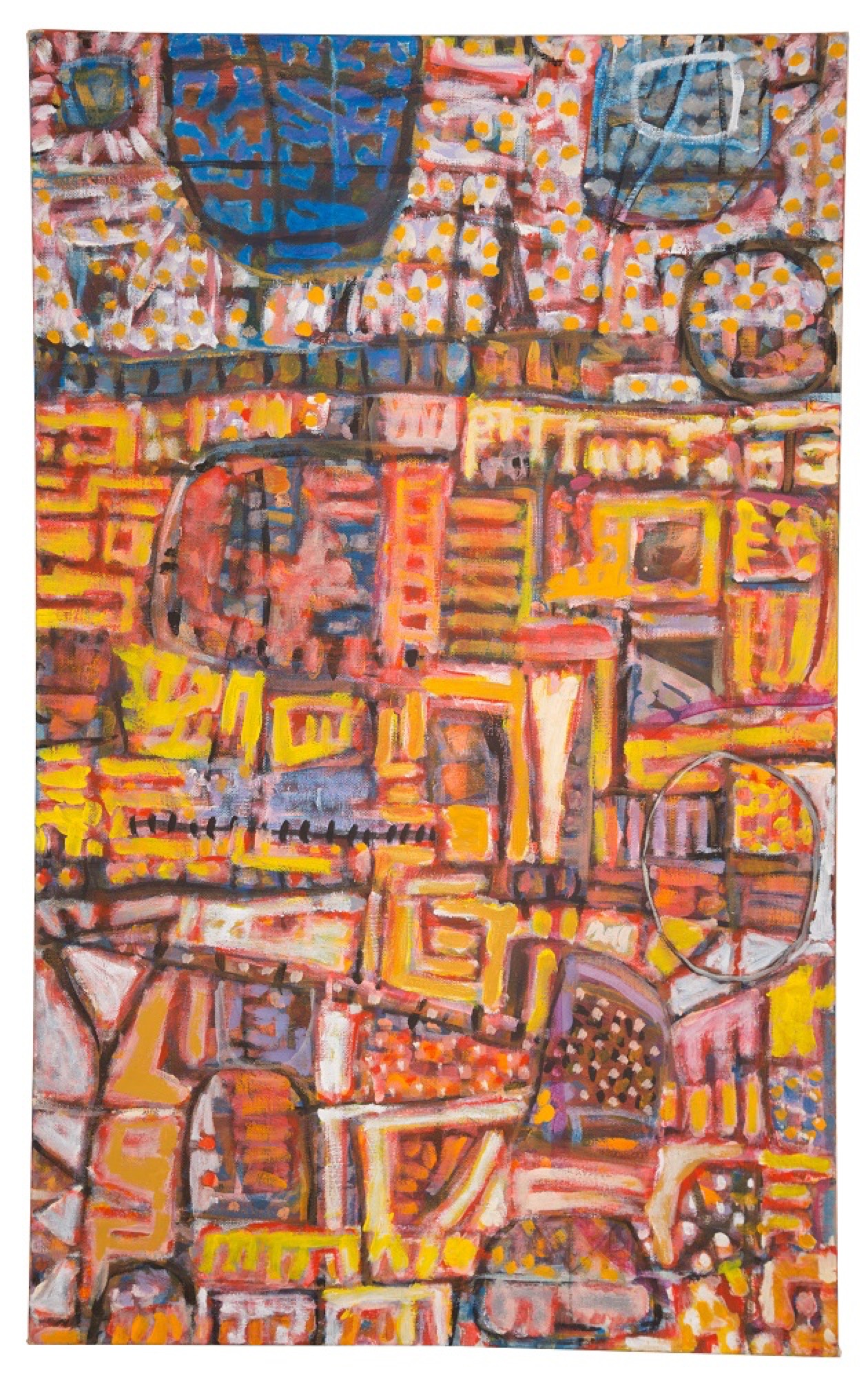

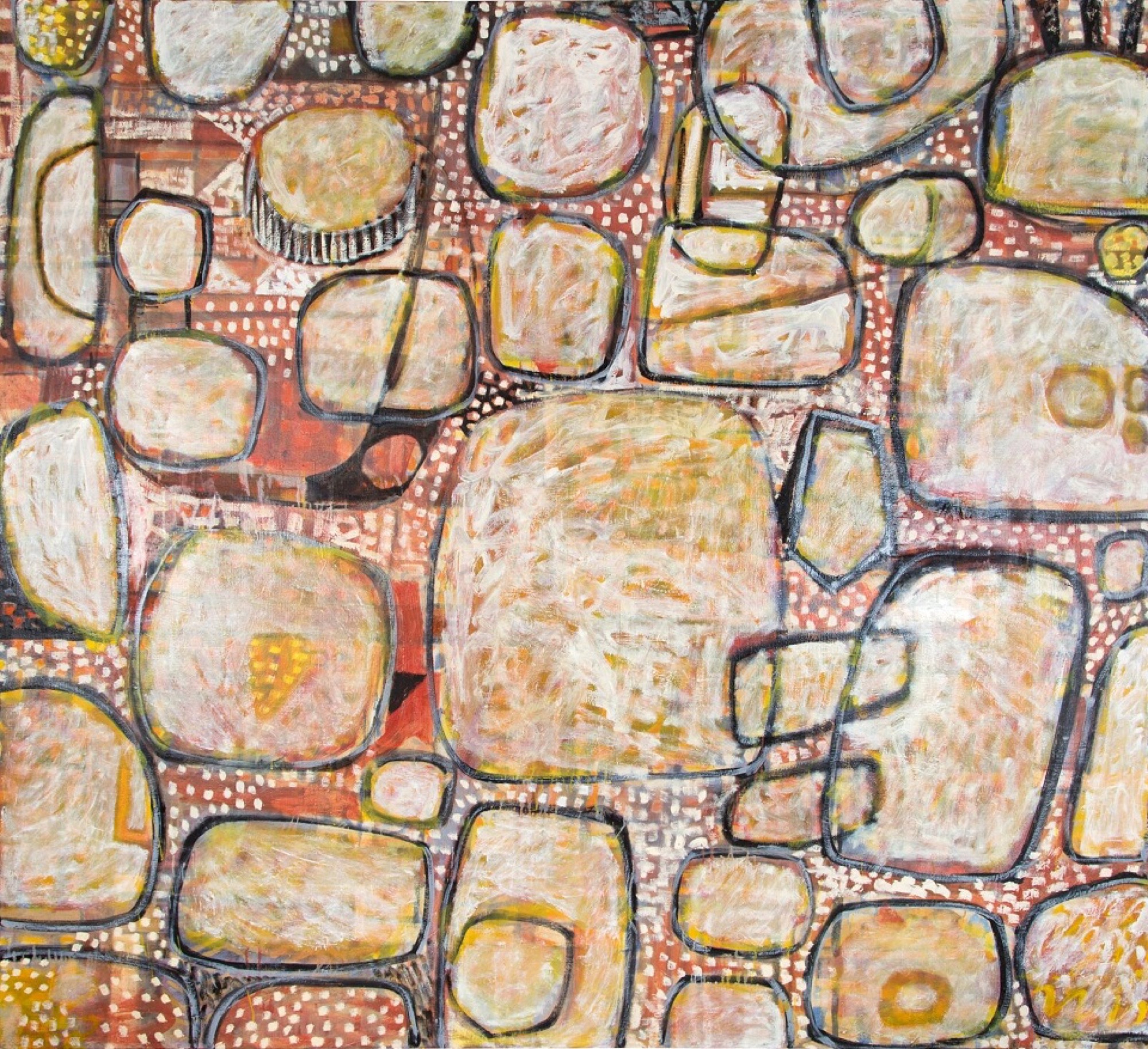

Eager's best paintings have a lyrical lightness rarely evident in the earnestness of the Melbourne Style. Wayne Eager New Paintings gives us a glimpse of what the old Melbourne Style might have been, if not for the revolution. However, I don't intend to descend into either counter-revolution romanticism or nostalgia by holding Eager up as someone who defied history or the artworld or evaded its conventions as some still like to think art can do. Rather, history and the artworld simply ignored Eager while he, oblivious, continued making paintings in an inherited but anachronistic tradition. Raised in the insular conservative ways of the old Melbourne Style (both his parents were painters), Eager remains true to the aesthetic values of Parisian modernism, especially post-cubist ways of organising pictorial space and surrealist iconography (both, as it happened, were inspired by Indigenous art, which as we shall see also has some bearing on Eager's course). In this Eager seems to take his cue from the old Melbourne Style in its final abstract years of the mid-60s – as in the work of Roger Kemp, Fred Williams and outliers like Ian Fairweather.

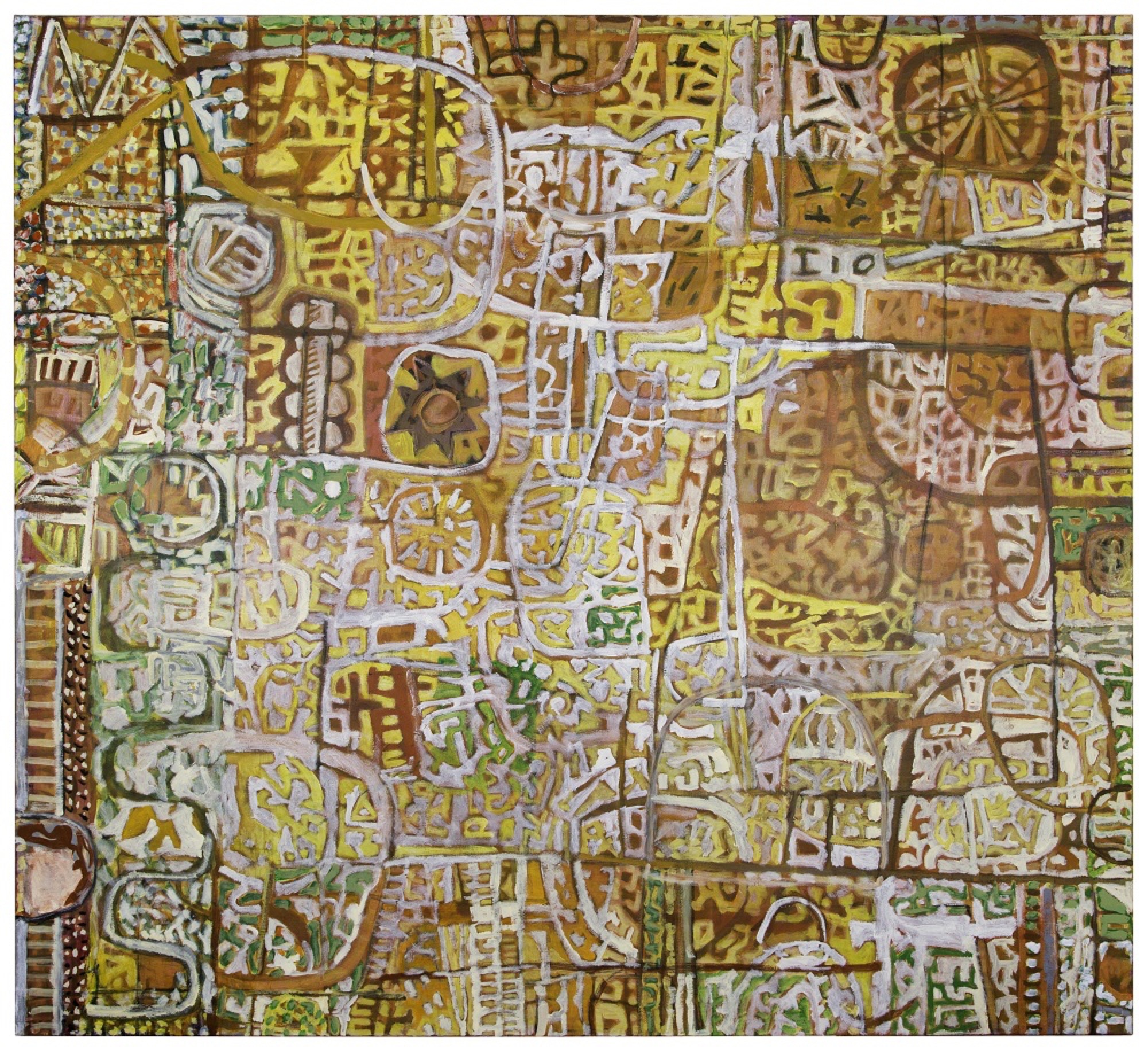

Fairweather, who despised Melbourne when he lived there for brief periods in the 1930s and '40s, would seem Eager's most important touchstone. While not derivative of him, like Fairweather's paintings Eager's slow the eye as if readying it for a performance. For example, rather than brought to the finality of resolution, Percussion leads the viewer's eye in meandering circles until the pictorial space gradually gathers to a certain pitch or perhaps pulse.

Just as music can only be heard by those with an ear that can follow the modulations of its playing, so Eager's paintings can only be seen by those with an eye that can follow the lyrical moves of its making. Like listening to music, seeing Eager's paintings is a temporal event: unlike the instantaneous experience of the image, Eager creates a pictorial space that only comes fully into view over time. They are paintings that grow on and with you. And like music they are best experienced live, in the space and scale of the event. Needless to say, the reduced size of the images on the gallery's website and the exhibition pamphlet flatten the pictorial space they purport to reproduce – though the examples on the pamphlet have been well chosen and indicate the range of Eager's pictorial schemes.

Missing in Eager's paintings for a contemporary viewer, and also for someone of Clement Greenberg's ilk to which you might think these paintings would appeal, is an ideological agenda – be it an ideology of art, identity (ethnic, gender or nation) or politics. Eager is not even a retro-modernist, in the manner of so many contemporary artists, but out of our time and our place because he is so stubbornly in the time of his place.

Eager's problem has always been finding a subject, not animating paint. This exhibition, his most impressive of the few I have seen over the decades, finds its subject in the making of paintings, as if its rituals take him to ground, or at least to where he wants to be. Perhaps this is what he learnt from the Western Desert painters with whom he has had close personal associations for a quarter century. What he could teach them about the artworld is beyond me, but there seems to be an affinity between his and their way of being through making paint sing on canvas. Perhaps this is why I, somewhat sentimentally, think of Eager as a modern-day Rex Battarbee, that practitioner of the old Melbourne Style who in the mid-20th century found a home in central Australia through painting with his Aranda friends.

Professor Ian McLean is Hugh Ramsay Chair of Australian Art History at the Univeristy of Melbourne.

Title image: Wayne Eager, Kinetic , 2017, oil on linen, 175 x 200cm)