Sidney Nolan and Elwyn Lynn: A Joint Centenary

Jane Eckett

A shared centenary, mutual admiration and a friendship spanning the final quarter-century of their lives are the ostensible justifications for the present joint exhibition of Sidney Nolan and Elwyn Lynn at Charles Nodrum Gallery, Richmond. Their friendship also extends to provenance. Fifteen years ago Nodrum showed a suite of over two-dozen drawings that Nolan made over the course of a single afternoon, in 1984, on Lynn’s veranda at Moncur Street, Woollahra, as the two men talked and drank (tea and coffee, we are assured, not grog). A further eight works from that series are shown here for the first time, providing a logical hinge for the joint exhibition. Yet, as the show reveals, Nolan and Lynn shared much more than simply friendship. Ideas, concerns and passions spark from one work to the next, while doubts about the nature of mark making, figuration and representation trouble the undercurrents of many of their works.

Among the most self-evident of correspondences is the surrealist delight in unlikely juxtapositions of objects and forms. Nolan’s Seated Figure with Faces presents a headless female torso with not one but four faces superimposed variously over her breast and hand and jauntily tucked under an arm. Four illustrations to Robert Lowell’s poems, dating 1966-67, evince a similarly surrealist conjoining and overlaying of male and female figures—their economy of line and limb resulting in barbaric biomorphs in various states of ecstatic union. They sit well alongside three suites of Nolan’s lithographs inspired by Dante’s Inferno, in which predominantly armless men and women tumble awkwardly down or across the page like so many bound cadavers, bodily parts intermingling and—in some cases—covered in weeping red and blue stigmata. This is a relatively well-known version of Nolan, though it is worth underscoring the surrealist intent that persists throughout his mature work.

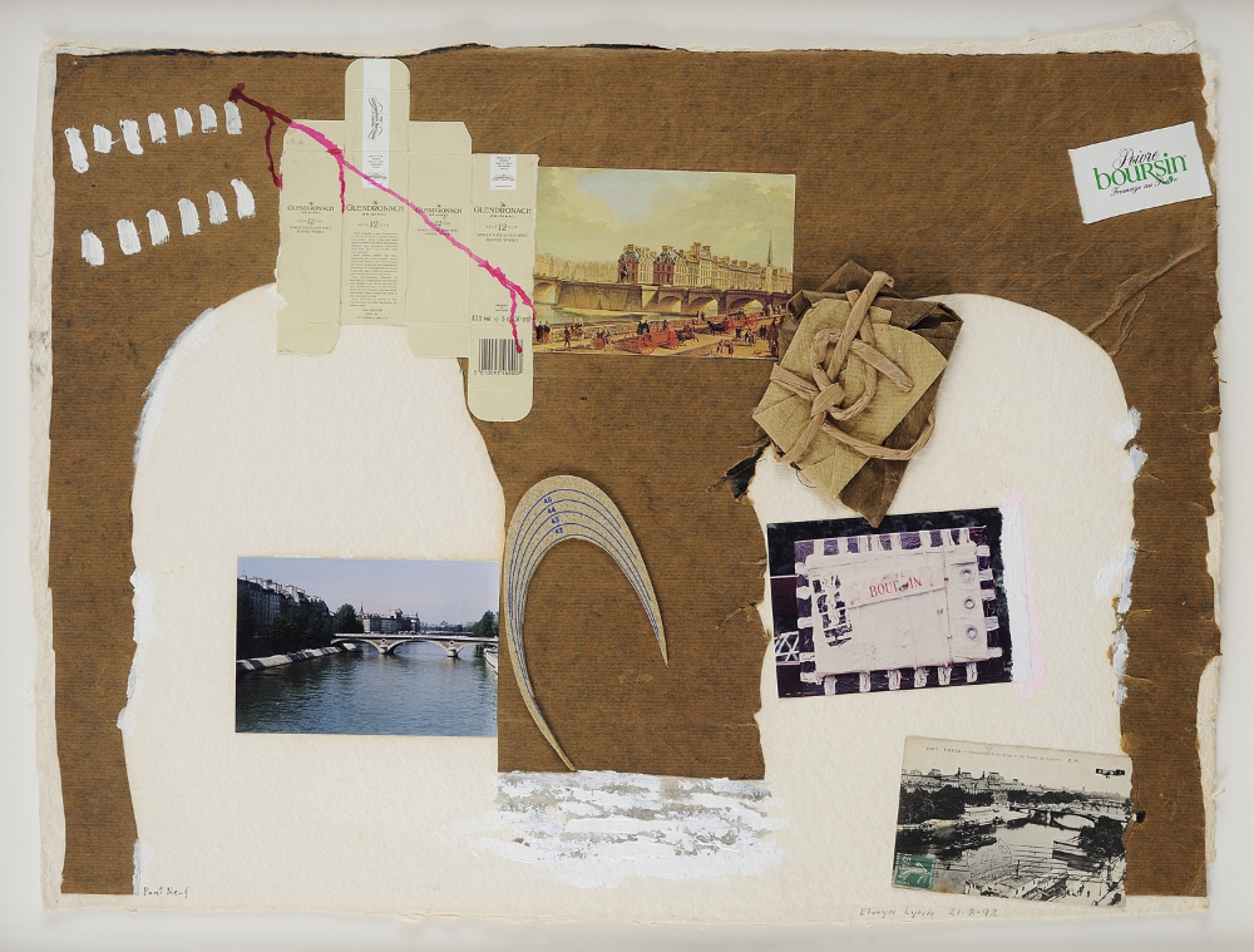

Lynn’s collages draw together scraps of newspaper headlines, banner-heads and articles with photographed pages from a herbarium and other incunabula, postage stamps, wax seals, a playing card, postcards of Japanese woodblock prints, a magazine photograph of one of Monet’s snow scenes, a reproduction Confederate banknote, strings, packaging from some ready-made French vegetable soup and several utilitarian hardware items, including a paintbrush and a rather cruelly-shaped hawkbill knife, which is traditionally used for cutting rope (appositely, given Lynn’s predilection for tying his work up with a multitude of different types of rope, string and twine). Sometimes his collages pivot on a theme. For instance, Pont Neuf, 1992, assembles antique and contemporary postcards of the eponymous bridge with packaging from Boursin cheese (beloved by generations of Australian travellers and expatriates) and an airline bottle of Glendronach whiskey, as well as a postcard of what appears to be a Robert Ryman all-white canvas and a crescent-shaped piece of card marked with cartographic contours, all pasted over an arched bridge-shaped form torn from brown packaging paper. Made during Lynn’s three-month Cité Internationale des Arts residency, Pont Neuf conveys a sense of foreign-ness—the sense of an outsider meditating on French history, on the significance of rivers for trade and transport, and on the intersection of art and the quotidian in a city steeped in cultural capital.

I suspect it was this sort of sophisticated visual erudition on the part of Lynn that attracted Nolan—just as much as Lynn’s highly evocative writing, particularly as it applied to Nolan’s own work. Both men were inveterately inquisitive about the world; Europhiles who nevertheless extended their curiosity to temporally and geographically distant cultures. We see this in a striking large spray-painting of Nolan’s: Bombing of Berlin, 1984. Seemingly responding to the Allied bombing of Berlin during the Second World War, Nolan’s notebooks from this time record he was actually thinking about the loss of the Buddhist frescoes from Bezeklik, in northwest China. Large fragments of these frescoes were moved in the nineteenth century and mounted on the walls of Berlin’s ethnographic museum, only to be destroyed during WWII. The violent clouds of purple, black and white spray-paint recall the effect of both fire-bombing as well as graffiti bombing, while the leering face in brown that floats on top and amidst these clouds is less Buddhist deity than carnival clown. Figure and ground bleed together, a second ghostly face is visible through the first, and the history of disparate cultures (Uyghur and German) become superimposed and compressed. Lynn likewise drew sustenance from travelling to and reading about distant cultures. Yokohama, coincidentally also from 1984, takes its title from a collaged strip of postmarked stamps and responds to the spare geometries of Japanese prints with a deliberate roughness that resists the temptation to calligraphic elegance. Formally, however, it echoes the hill-like composition of two slightly earlier works of Lynn’s, Tree Top Table and Wurtzburg, both from 1982, suggesting a conversation traversing east and west. Dallas, 1990, collages newspapers from New York and Dallas with two pages from—if I’m not mistaken—Art Monthly Australia, reporting on sales of Australian art including, amusingly in the present context, one of Nolan’s Kelly paintings. The effect is to embrace the local in the international, highlighting the implicated nature of art within global financial systems.

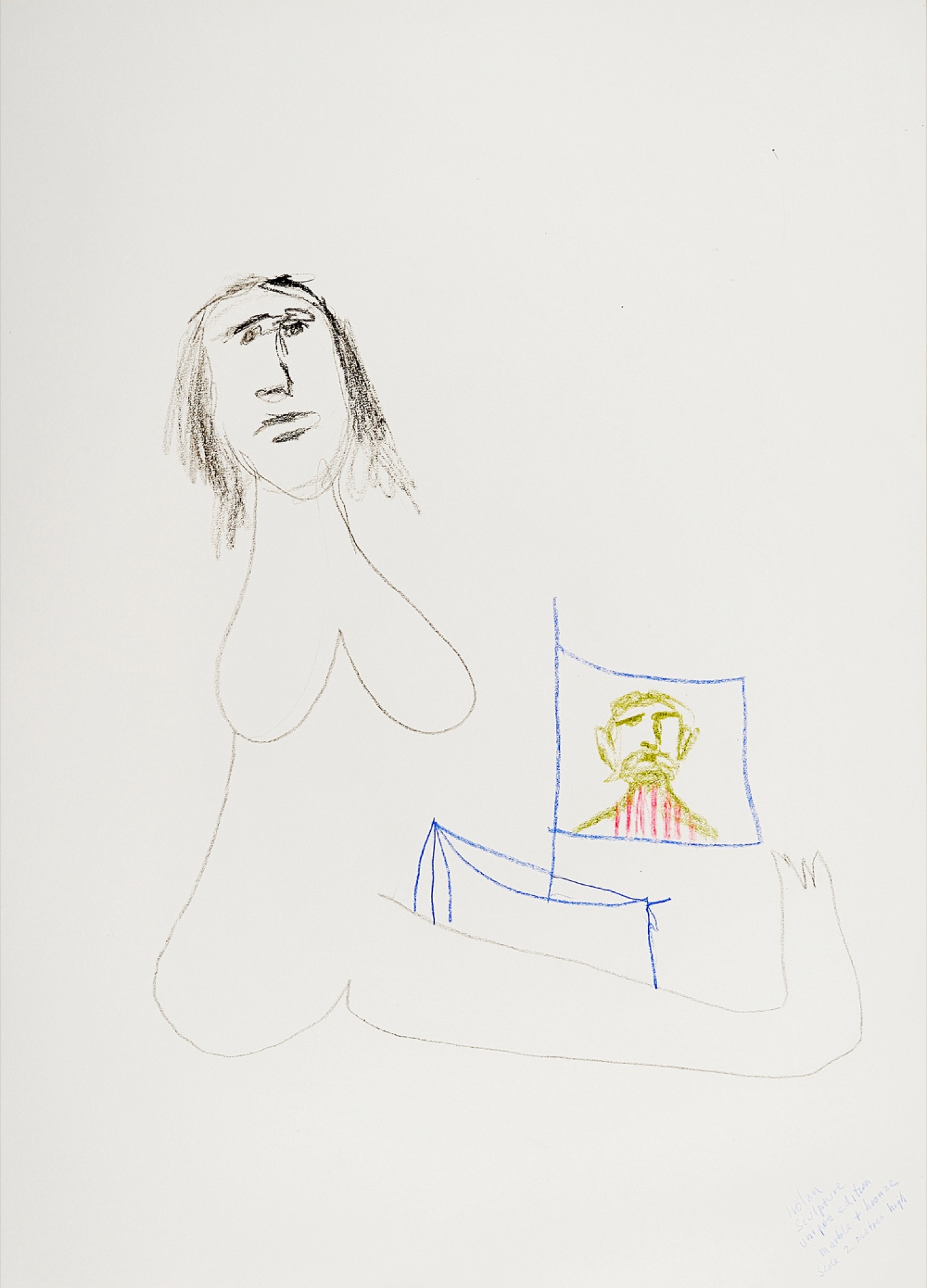

The exhibition contains a number of other surprises. Nolan the aspirational sculptor is one such. Three large crayon drawings, provisionally dated c. 1980-89, each bear the inscription: ‘Nolan / sculpture / unique edition / bronze + marble / scale 2 metres high’ (or 3 metres wide in one instance). Leaving aside the bombast of the proposed scale and expensive materials, it is worth pausing to consider what Nolan envisaged. In each case we have a seated female nude, limbs stretched uncomfortably forwards as though groping for her toes in an exercise class. A small clitoris-shaped boat balances in her lap; in one version, the boat is filled with flowers while in the other it is crowned with an erect flag emblazoned with the face of a bearded man. In the third work the woman’s groin area is haired, with the colour echoing the hair of the dog that balances on her outstretched arm. While scarcely subtle as erotic emblems, they are equal parts comical and confronting when imagined scaled up to larger-than-life-size. A little-known aspect of Nolan’s career is that he toyed with the idea of making sculpture since at least 1952, when he joined the Society of Sculptors and Associates in Sydney. His promise to submit work to their annual exhibition came to nought, and it was only in later life that he produced four small figurative works that were cast in gold. The present series of drawings suggests a much grander vision and a larrikin engagement with notions of monumentality and permanence.

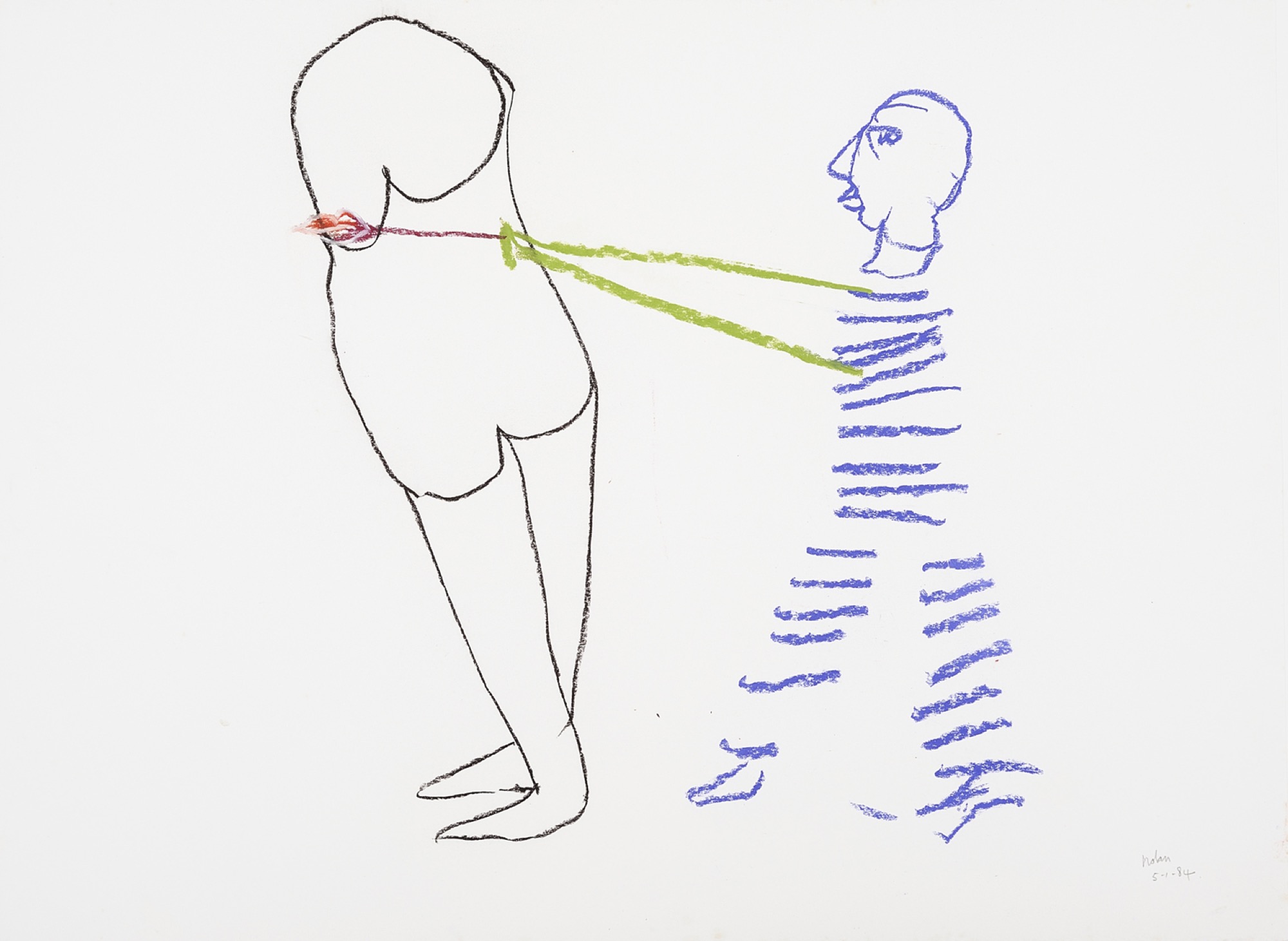

Nolan’s views on the relation between artist and muse are essayed in four drawings from the 1984 suite made for Lynn. In one, Artist drawing a nude, the artist wields his brush like a lance or red-hot poker, prodding the headless figure of his model. Interestingly, only the model is outlined; the artist exists merely a series of horizontal stripes, without any constricting outline, suggesting it is his role to delineate rather than be defined. In Artist and cat with painting the brush seems to pull the artist forward, magnetically attracted to the easel picture of a woman’s head, while the artist turns to face us (or his model), unconcerned with the largely automatic process of applying brush to canvas. The brush is wielded as magic wand in Artist and reclining figure, whimsically granting wings of flight to the insect-like figure of the nude. These alternate renderings of the artist’s brush—as lance, magnetic rod and wand—suggest a degree of equivocation on Nolan’s part; was he hunter, hapless captive or conjurer?

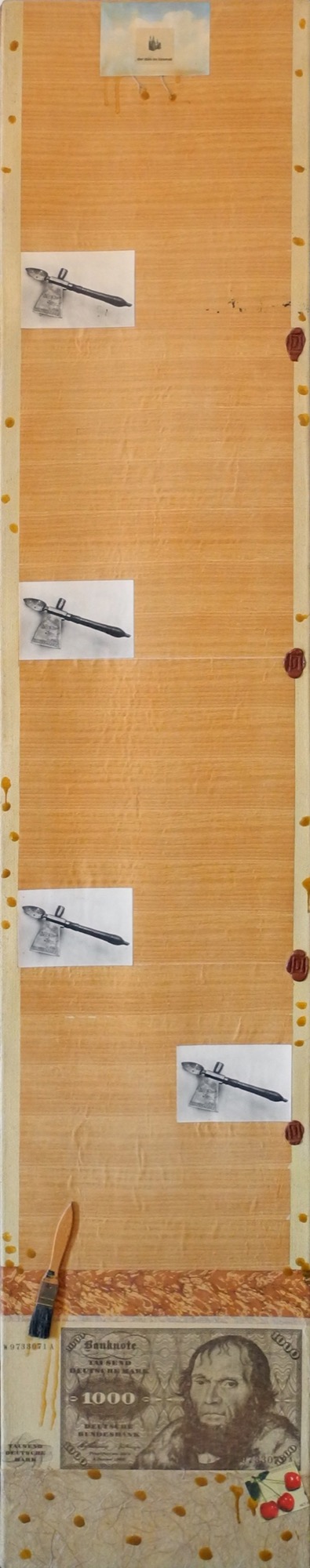

Other surprises include Lynn’s five dramatically elongated canvases from 1973-74, which announce the upstairs galleries from the stairwell. Two of these pivot on ‘artistic’ photographic nudes taken from magazines and focusing—Boucher-like—on buttocks (the title of one such, Mirrored Cheesecake 1903, 1974, lending a wryly pornographic tenor that the collaged magazine scrap might otherwise have not conveyed). Initially, these seem a far cry from the interest in corroded and crusted surfaces and landscape referents that we usually associate with Lynn. Yet they establish a dialogue of sorts with the earlier Dry Moraine, 1968, which hangs nearby. The thick skin of paint mixed with PVA glue, sand and pebbles in the earlier work is now stretched and diluted to support a panoply of collaged found objects, thinned and dribbled paint, textile fibres and printed textures—that is, photographs of wood graining rather than actual pieces of timber. Placing real objects against reproduced objects, Lynn takes up the classic cubist strategy of confounding any sense of containment or imagined window-onto-the-world.

Although this is a small exhibition and the occasion for it largely fortuitous, an accident of Nolan and Lynn sharing the same year of birth, it nevertheless affords us a chance to critically engage with the work of two Australian painters whose work might presumed to be well known yet is still capable of delivering surprises. Lynn’s contribution to Australian art remains under-acknowledged; his work as a writer, critic and curator of the Power Gallery of Contemporary Art (1969-83) has lately begun to be re-examined, but his art has largely eluded a major assessment. Perhaps this is because the metaphor of decay that preoccupied him throughout his career resonates most clearly with those Spanish and German matter painters he most admired (particularly Tàpies), rather than with the large-scaled bravura of the New York School, which Lynn himself, by 1959, recognised had eclipsed the various European schools and which continues to dominate narratives of post-war painting. In contrast, Nolan is over-exposed. Yet certain aspects of his career are still awaiting substantive treatment. The late spray-paintings of the 1980s might be seen in relation to the rise of street art, particularly in New York; an exhibition currently on at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, as part of the Nolan Trust’s centenary celebrations, might throw new light on this series. And, as the Nodrum show demonstrates, Nolan the unknown-sculptor deserves further investigation. Modest though this show may be, it opens multiple avenues for new interpretations—a fruitful, if unexpected, outcome.

Jane Eckett is a sessional coordinator in the art history and gender studies programs at Melbourne University.

Title image: Elwyn Lynn, Yokohama, 1984, gouache and mixed media on paper, 56.00 x 76.00.)