TarraWarra Biennial 2023: ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili

Luce Nguyen-Hunt

As I stand in the centre of the ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili, I notice that my breath and heartbeat are in tune with the sounds and echoes of the room. I can hear the faint greh greh (grunt) and groh groh (deeper groaning sound) of Leyla Steven’s video, the electrical hum of Elyas Alavi’s neon creations, and the rhythmic sighs of Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s clay lotas. The whispers and gentle footsteps of other visitors remind me of our connected role in community and kin. The museum vibrates with tension and grace. The space feels charged: like a resting place for collective and vast Oceanic ancestral memories. As a kindred viewer, I am not only struck by the heaviness of the works but also by the weight of piri’anga (connection / relationship / intimate). Mana (spiritual lifeforce of Oceania) is here, and she is grounding.

Framed by the alagā‘upu (Sāmoan proverb) translating to “the canoe obeys the wind”, ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili archives a small piece of the Majority World’s cultural rebirth, igniting Indigenous memory through language, movement, and energetic pulse to channel and look to our matriarchs. Championing fifteen new commissions alongside an extensive program of artist talks and performances, ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili reflects the rigorousness of these artistic and curatorial practices and the endless conversations they generate.

There is a distinct spiritual balance and equanimity to this particular suite of works and their arrangement, a characteristic I have witnessed in other shows curated by ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili’s curator Léuli Eshrāghi, including Ua numi le fau at Gertrude Contemporary (2016) and ʻO le ūa na fua mai Manuʻa at UNSW Galleries (2020). Eshrāghi has a way of prioritising the connections between histories and artists whilst acting as an advocate for the very real and present experiences informing these works. As an emerging artist myself, I struggle with the institutional compulsion to frame ostracised identities as trauma porn; it can be so counterproductive to fostering human connection—plus it is often daunting to share loaded experiences with white curators. Perhaps it’s wishy-washy, but to me Eshrāghi’s curatorial projects stand out because they are so full of heart.

Eshrāghi is generous with knowledge-sharing in the wall labels and extensive catalogue essay, but I also appreciate the details and readings that may only be accessed by individuals from the artists’ respective communities. Indigenous Oceanic knowledge often cannot be read about or researched but only seen, felt, and shared in stories; Eshrāghi does little to console those with a white saviour complex. The works and their histories, artists and their communities, are connected and in ongoing discourse, evident in Eshrāghi’s chosen installation that largely does away with physical boundaries, territories, or walls to distinguish works from one another. The interactions and intersections of many histories / herstories addressed in the show pre-date Western intervention, so in many ways Eshrāghi is acknowledging what has always been.

On the opening weekend, audiences were invited to witness a performance by Unbound Collective, a powerful homage, lament, and spoken word piece dedicated to the endangered mangroves in the Kaurna Yarta. An ephemeral extension of Unbound Collective’s two-channel video and natural fibre skirt installation, PERMEATE/mapping skin and tides of saturated resistance (2023), this performance called attention to the irremediable salt toxicity of mangrove forests—a critical lifeforce for the surrounding ocean. Beginning with a procession through the gallery, the audience slowly followed as Yidinyji and Mbararam artist and scholar, Faye Roasa Blanch, and Narungga artist and scholar, Natalie Harkin, shared visceral and somatic poetry about mangroves, evoking the essence of bodily sensations and oneness:

With every fourth breath, we give

Hear us call out

Like your salt of the earth, we rise

Our poise balanced; refusal to disappear

Mirning artist and scholar, Ali Gumillya Baker, and Yankunytjatjara artist and scholar, Simone Ulalka Tur, looked into audience members’ eyes with an unwavering gaze, holding no space for colonial fragility. This important point of connection beckons us, settlers of this country, to take accountability for our heavy presence on this land and the many ways we threaten it. Rhythmically framed by the heavy sighs of every fourth breath, there is no diverting the rage and grief of the ecosystem.

Certainly, ephemeral performance is an abundant and intrinsic part of ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili, gesturing to the importance of personal engagement with the artists as well as returning to fundamental forms of storytelling and knowledge sharing oral tradition. Artist and abolitionist Bhenji Ra also performed on the grounds of TarraWarra for the VIP opening to accompany her video work Trade Routes (2023), weaving her way through the vineyard before entering the galleries.

In Trade Routes, we see layers of people, place, identity, land, water, culture, rural and urban settings; no matter where Ra is physically, she is connected to each place and time simultaneously. As part of an “accidental archival practice,” Ra documents her reinvigoration of ancient trade routes in a single-channel video work. In a flurry of blurred, overlapped, superimposed and abstracted footage spans Indigenous lands across Wurrumiyanga, Tiwi Islands, Davao, Philippines, Oaxaca, Mexico, Kingston, Jamaica, and Tongvaar (Los Angeles). There is something comforting about seeing flashes of familiar faces from the community, not to mention the video’s soothing fast pace for my ADHD brain.

As we watch Ra’s video, we disregard time as a strict measurement and experience it instead as a cycle of divine universal rhythms, patterns, recurrences, and deeply spiritual movements. Whenever I engage with Ra’s practice, I am reminded that the body is an archive and our movement is sacred—our dance and poise as people of Mana is located deep within ancestral blood memory and space. There is an endearing intimacy to the woven quality of this digital diary, mimicking storytelling with natural fibres and the act of braiding, interlacing, merging, and blending. It feels important that Ra has selected footage where she is always behind the camera, as if to allow us a glimpse into her gaze or to situate us as witnesses to her storytelling and generous teachings.

In a similar vein to Ra’s ancestral movement practice, Leyla Stevens’ cinematic beauty GROH GROH (Rehearsal for Rangda) (2023) draws upon restorative diaspora-centred invigorations of Rangda, the Balinese demon queen. Rangda exists outside of many binaries, occupying the feminine and masculine, creator and destroyer, as well as interfering with concepts of the nurturing mother by becoming something othered in fear. In the film we follow a group of young women unlearning traditional gestures of divine femininity, and unrepressing their instinct to internalise. Now their aggressive and unrepressed facial expressions and uncoordinated movements breathe new life and energy into the spirit of this matriarchal witch.

Traditionally performed by men, the final scene shows heavy metal vocalist and collaborator Karina Utomo summoning Rangda in a monumental performance. I got chills from the animalistic grunts and groans as Karina offered herself as a vessel to channel the aberrant and vile energy of this powerful ancestral manifestation. Bathed in a red glow, this version of Rangda features an almost indistinguishable face covered in long dishevelled hair adorned with layered dark garments. This representation alludes to the presence of the fire element—dangerous, violent, destructive but also regenerative, passionate, and hard to resist.

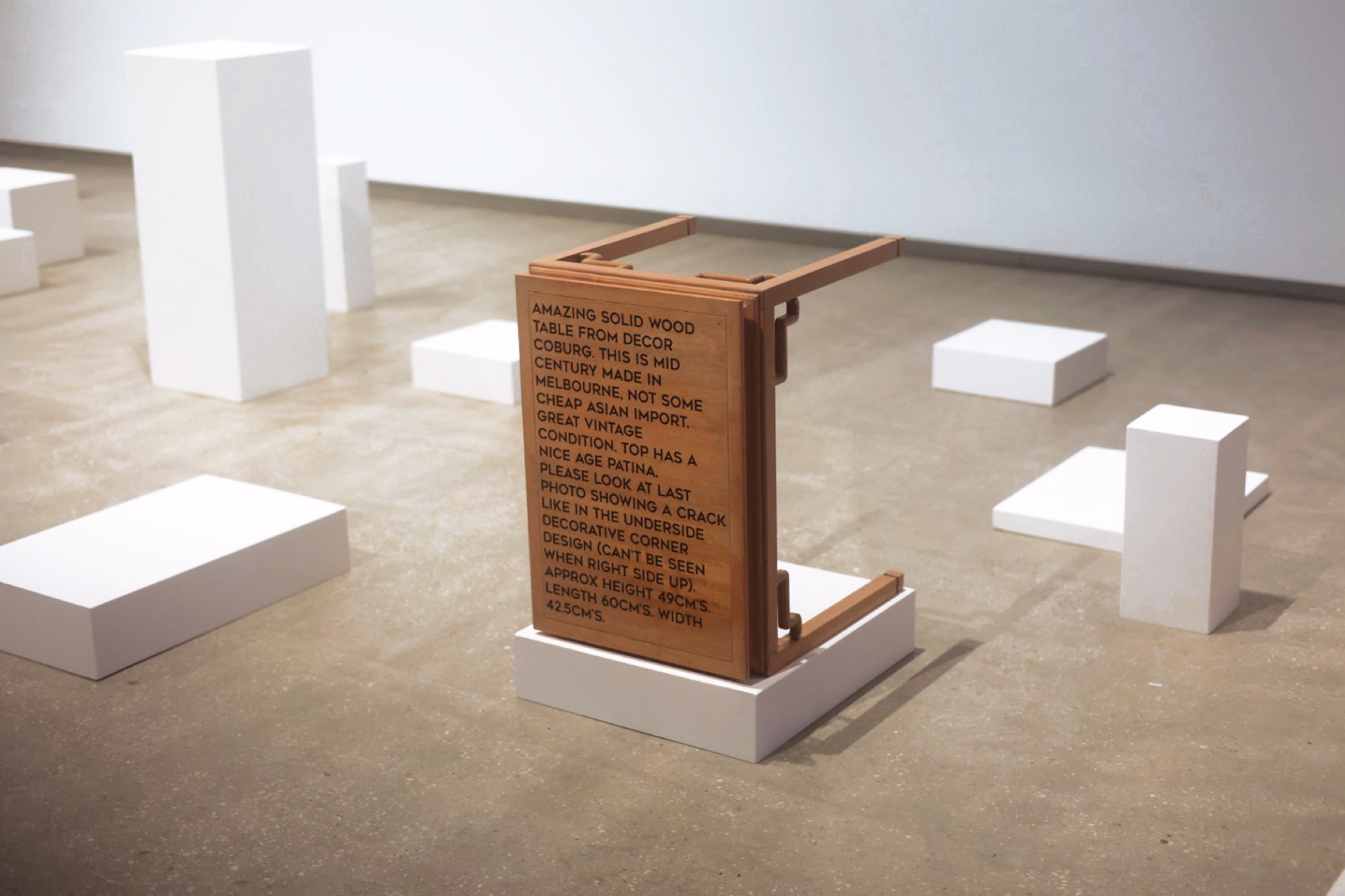

Just outside Steven’s cinema space is Phuong Ngo’s Remastered (2023), a series of precarious plinths constructed from collected furniture dating pre-1963. Amidst the mismatched plinths is Facebook Marketplace clickbait: a mid-century modern side table imbued with the seller’s not-so-charming description “not some cheap asian import.” Against the backdrop of the White Australia Policy and its racist legislation, Ngo references the Victorian Factories and Shops Act 1896 that legally required furniture made in Victoria to be stamped with “European Labour Only.”

A Vietnamese-Australian artist whitewashes European labour histories and law through the language and aesthetics of contemporary institutional whiteness—literally painting it white. As a device, the plinth acts as the minimalist lovechild of the monument and is perhaps one of the most displacing elements of white cube infrastructure, particularly when it pedestals stolen Indigenous cultural objects. Upon closer inspection, we see that even numerous layers of the British Paints colour “White Comfort” cannot conceal the stains and textures of the once-furniture. The sad reality is that these racist attitudes towards Asian migrants and Asian Australians continue to surface today, whether in covert, targeted, fetish-driven or exploitative ways. Perhaps my inner rage when I hear complaints about spending ten dollars on a banh mi but happily splurging upwards of thirty-five dollars on a plate of pasta is actually justified?

Although at first Remastered may appear as an outlier in the show, I find its irony, sarcasm, and subversion humorous and evergiving. In the first weeks of ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili, there was significant patron feedback from Asian viewers who misinterpreted Remastered to be siding with racialised labour hierarchies. Highlighting the fallibility of condensed wall labels in the framework of repressive traditional museological practices, it is clear these structures do not aid deeply conceptual and layered works such as Ngo’s. In response to this feedback, an earlier version of the label that prioritised the artist’s voice swiftly became a replacement—with many layers of complexity and no one person at fault, sometimes it is difficult to mitigate the violence we seek to highlight in our works. This exemplifies a broader issue that artists of colour face when contending with overlooked and erased histories. Employing nuanced takes, coded systems or even inside jokes can leave unintentionally sour impressions, and it can be difficult to navigate, especially when viewers bring their own lived experience. Nevertheless, the best way to communicate didactic information seems an ongoing, unsolvable puzzle.

United by a collective awakening, a return to Indigenous memory and the importance of matriarchal knowledge sharing systems, ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili is a moment in time for Indigenous viewers of the global sphere. It is a chance for us to be reminded that the purest form of connection is an understanding of our position in relation to ‘enua (land) and moana (ocean), and in turn, help us steer our internal waka (canoe) wherever the wind may take it.

Luce Nguyễn-Hunt is an emerging Vietnamese, Sāmoan and Rarotongan artist and writer currently based in Naarm. Their research-based practice documents an evolving cultural gender-sexuality divergence through digitally manipulated moving image and photography installations. They use poetry, text and sound as an embodiment of cultural memory.