Truth, Beauty and Utility: the Arts and Crafts Movement in Heidelberg

Jarrod Zlatic

The Arts and Crafts Movement can be somewhat difficult to appreciate as a precursor to the modernism of the early twentieth century given its “return to tradition” ethos. Although it sought to clear the clutter of the eclectic Victorian style, it ended up with the air of an antique store, another historicism albeit more refined. This latent antiqueness makes the headquarters of the Heidelberg Historical Society a perfect location for the exhibition Truth, Beauty & Utility: the Arts and Crafts Movement in Heidelberg, curated by Steven Barlow. The society is housed in a nineteenth-century courthouse, with the exhibition beneath the dark wood dome of the courtroom. The society’s archive bleeds out onto the edge of the exhibition space as plastic boxes, bags and bound volumes peek out from beneath what was originally a magistrate’s bench.

The exhibition features printmaking and pottery, though the primary focus is domestic architecture. These are the numerous houses in an Arts and Crafts style that cluster along the leafy recesses and rolling hills of the surrounding suburbs of Heidelberg, with the ubiquitous Californian bungalow now the movement’s most present form. An architectural mash-up of Tudor gables, timber shingles, stucco rendering, beaming sunrise-like porches, Japanese-derived “Tori gates” and so on, these were the work of mostly anonymous building companies that produced endless refrains on the bungalow from the late 1900s through to the end of the 1930s.

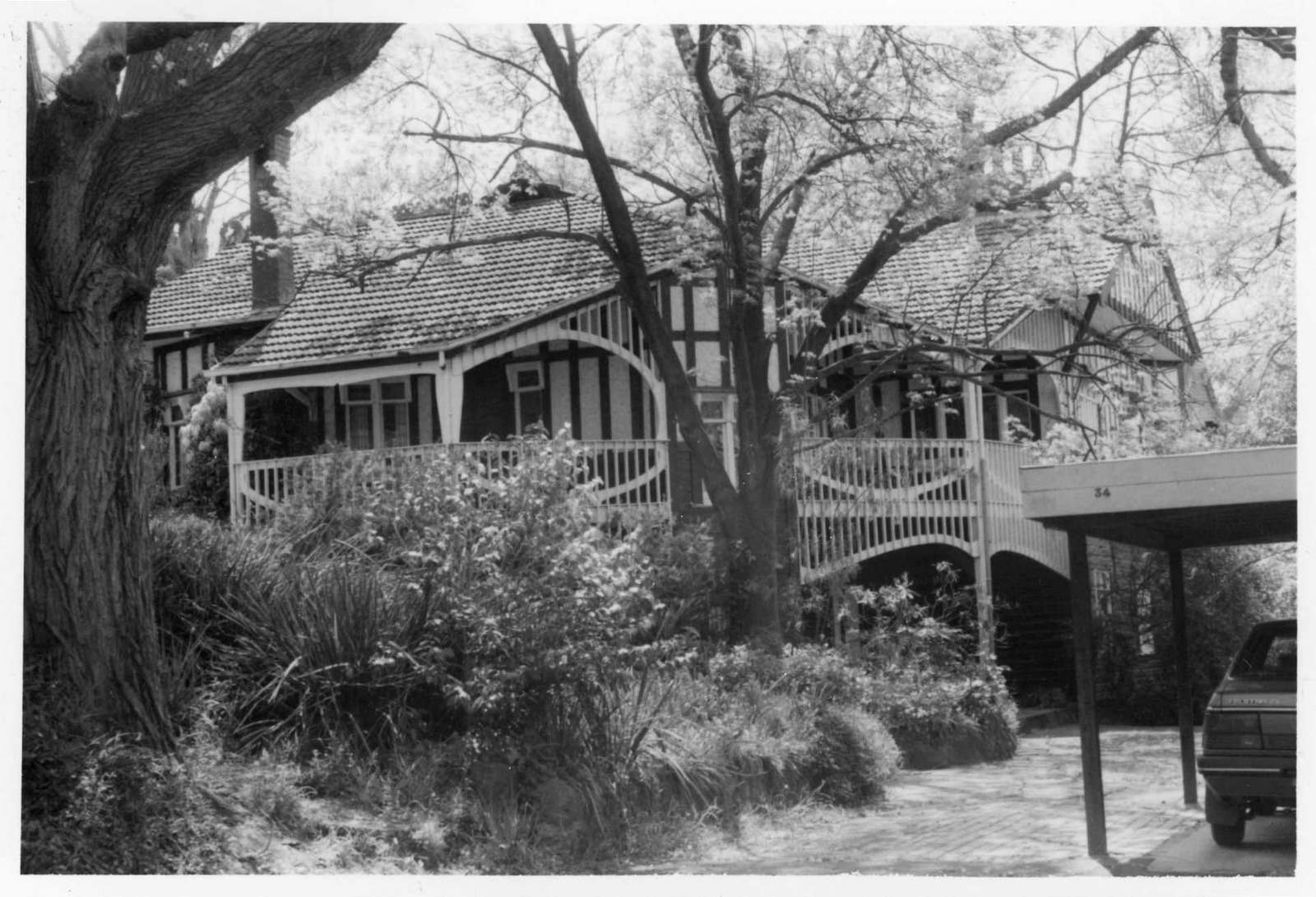

The influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Melbourne was not limited to Heidelberg. It is in Hawthorn, Kew, Camberwell, Toorak and Malvern where the major building commissions are and where the membership of the Victorian Arts and Crafts Society lived. Rather, Heidelberg was home to two of the major contributors to the movement in Australia, beginning with the architect Harold Desbrowe-Annear. He was one of the founding members the T-Square Club, early promoters of Arts and Crafts principles, and a direct precursor to the establishment of the Victorian Arts and Crafts Society. While living in the Heidelberg area, he designed a trio of distinct houses in Eaglemont in 1903, the most notable being Chadwick House. It combines typical Arts and Crafts features with Desbrowe-Annear’s individual touches, as seen in the unique, curving design of the verandah and the flowing, internal layout.

Desbrowe-Annear was an active member of Melbourne intellectual and artistic circles, and his connections to the art world are reflected in his local commissions. He designed houses for the painters William McInnes (who would win the first Archibald Prize with a portrait of Desbrowe-Annear) and Norman McGeorge, while Blamaire and Mabel Young resided for several years in one of his Eaglemont houses. After the exhibition, driving around to spy these houses, a unity can be seen in Annear’s distinct take on the Swiss-cum-Tudor manner, now all restored to their original Red Leicester yellow rendering.

The artist-couple Christian and Napier Waller are the other focus of Truth, Beauty & Utility. Although they shared an interest in the principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement going back to at least 1910, they provide a bookend to the movement’s direct influence in Melbourne. It was in 1926 that they moved to Fairy Hills (now Ivanhoe East), designing and building an Annearesque house beside the Yarra. The house was decorated in a total style, with most of the furniture designed by the couple, hand-painted with their romantic, medievalist figures, and the walls were also adorned with their own work.

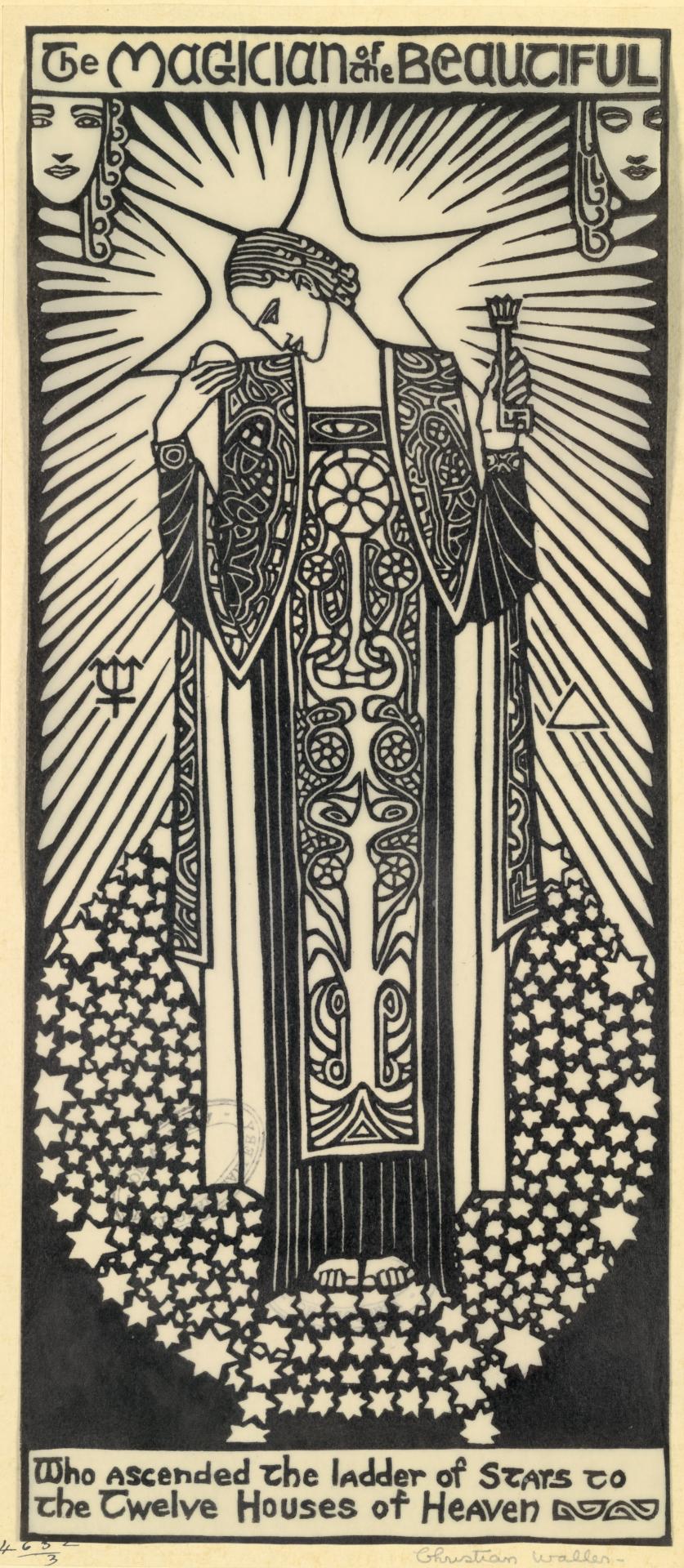

They were commissioned to undertake many striking, vitalist mural and mosaic designs for major public works, though they were most prolific in their stained-glass pieces for ecclesial settings. In the spirit of independent craftspeople, the Wallers’ work was all produced on their own printing press and home studio. A highlight of the exhibition is the display of Christian Waller’s portfolio of linocuts, The Great Breathe (1932). Inspired by the size of medieval manuscripts, the tipped-in prints are surprisingly large in-person. Their art deco style is severe, and the reduced design style emphasises a cold and somewhat threatening aura to Christian’s theosophical and Celtic portraits. Far from a flight into frivolous fantasy, the passive stone-faces of the Hyperborean races suggest malevolence as much as enlightenment.

Included in the exhibition are also several pieces of pottery by Napier’s niece Kyltie Pate, who lived with them at Fairy Hills. Pate might not be described as an Arts and Crafts artist per se, only beginning to produce work around 1930. The influence was at a remove, filtered through Christian’s own idiosyncratic and increasingly mystical interpretation of the movement’s principles. But Pate, and the Wallers’ artistic circle more broadly, are one example of the Arts and Crafts Movement’s long afterlife. In fact, the Wallers’ and Pate were connected with various artists interested in the printmaking associated with Harry Miller Tatlock, which was published in his Manuscripts magazine. Far from being successive movements, Tatlock’s magazine provided a platform linking older Edwardians and a younger generation of artists, united by an interest in the new medium of the linocut and the corresponding revival in bookplate design. These older artists, like the Wallers, had a background in Arts and Crafts principles and printmaking, but they were receptive to vaguely cubist approaches during the 1920s. These included mainstays such as Margeret Preston and Eveline Syme, though Tatlock also published work by artists such as Edith Alsop, who had exhibited with the original Victorian Arts and Crafts Society in 1908 and later undertook study with André Lhote in 1929.

Inevitably, the problem that faces any exhibition where architecture is the prominent focus is that buildings are exceedingly difficult objects to display. While there is Ishtar Gate at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin or Shiro Kuramata’s 1988 Kiyotomo sushi restaurant now inside the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, these are rare exceptions. Typically, architectural plans and models are the next go-to, either on loan from an architect’s archive or taken from the museum’s own collection. This avenue, at least for a small, volunteer-run organisation like the Heidelberg Historical Society, is also not viable. Given this, the Society’s current exhibition is relatively ambitious in its scope. In lieu, the exhibition has used old advertisements and pictorial pages from architectural journals, a variety of ceramics and bric-a-brac.

Much of the exhibition is photographs. These include a photo-book published in 1927 by local businessman Herbert Olney to proudly showcase Yantaringa, his Arts and Crafts style house, capturing its rich, sober interior. Mostly, though, the photos are the work of society members, who have the required local knowledge to document many of the bungalows in the area. The reliance on small photographs, sometimes to illustrate isolated aspects of these houses, recalls the work of Patrick Pound. I couldn’t help but see Pound’s recent exhibition Under Lamplight with Albert Tucker, nearby at Heide, as a good fit for the society. The theme of electric lighting is a subject that one could imagine as having been featured by the society in the past.

Although the exhibition has that quaint and quiet quality one might normally associate with a local history society, exemplified by the red-carpeted panel dividers, the exhibition design is thoughtful. The wall dividers and display cases are occasionally lined with coloured prints of William Morris’ ubiquitous wallpaper designs, and although I am usually allergic to this sort of intervention it works surprisingly well here to break up the exhibition space.

It is surprising that the dog-eared, sepia-toned photo, the cliché of an historical society exhibition, is absent here (perhaps for this reason). The society does have several photos in their collection depicting Arts and Crafts style houses sitting atop Eaglemont in relative seclusion, including the Desbrowe-Annear houses. There is a photo from around the mid-1900s that depicts children posing in front of a collapsed hot air balloon tangled in trees in front of the Chadwick Houses. The hill looks quite bare, and although it looks down onto a small, nearby village it is mostly pastureland stretching off to the North-East. It is yet to lose the scenery typically depicted by the Heidelberg artists that forty years later Bernard Smith would venture out to, only to complain it was now just suburbia. These old photos also demonstrate how these houses, although notionally modern, belong to the end of another era. When built, gas lamps still lit the sparse streets of Heidelberg, turned off on nights either side of a full moon, and the Melbourne Hunt Club still held hunting parties that crossed the suburb, which was mostly paddocks. The Industrial Age impetus for Morris & Co. would have felt especially distant in Eaglemont. The Heidelberg area was, at least up until the suburban consolidation of the 1940s, an exit from that urban situation. Even now, driving around the twisting, hidden streets to spy the Eaglemont houses, they retain something of their secluded, first-wave provincial cottagecore energy, despite successive eras of development and re-development.

Property development is silently present in the exhibition. Among the photos are a few surreptitiously lifted from online real estate listings, marked by that icy blue tone and glowing lens flare common to the current commercial style. It is a shame that nothing from the Society’s collection of pen and ink illustrations by Margeret Picken were used to accompany these photos. Picken’s illustrations were for the real-estate advertisements that used to crowd the back pages of the local The Heidelberger newspaper in the 1980s and 1990s. Due to the limitations of printing on newsprint at the time, the clean drawings provided more detail than a small, smudged photo could. The illustrations might have also highlighted that tension between real-estate preservation and development acute to older, more affluent suburbs like Heidelberg.

Ironically, urban development was built into the semi-rural reverie from the very beginning of its glorification by the urban day-trippers of the Heidelberg School. Given that Australia is fundamentally a predatory, continent-wide property development, it seems fitting that the Heidelberg School itself was ultimately the outcome of a chance meeting between Arthur Streeton and the property developer Charles Davies. Davies was a partner in the Eaglemont Estate Company that owned much of the surrounding farmland. Davies was happy to grant Streeton free use of the dilapidated old farmhouse on the top of Mount Eagle. The work of the painters who flocked to Eaglemont, apart from presenting an urban aesthetes vision of the landscape, were also capturing what was intended to soon be history. They are not unlike someone now who photographs old milk bars and barbershops that are destined to become apartments.

Perhaps then the most future-focused work from these painters’ time at Heidelberg is a small painting by Charles Conder, Impressionists’ Camp (1898), which captures the grimy interior of the farmhouse. The majority of the work is a muddy, washed-out pink. Here the fabled “golden summer” is confined to its likeness in a small painting hung on the wall (incidentally the actual painting it was depicting would end up in the collection of Desbrowe-Annear). Outside, through the windows, is a murky, nondescript pale brown; it could be anything or anywhere, factories or flowing fields. It is hard to tell whether the painting suffered a period of neglect or if Conder was simply faithful in his rendering of rising damp and smoke stains. The grubbiness suggests run-down terraces and abandoned shop fronts converted into share-houses awaiting redevelopment as much it does the privations of the pastoral past. Back at the so-called beginning of Australian art is already the germ of gentrification, although here it is somewhat closer to the original gentry themselves.

The development of the area into suburbia took decades, and the semi-rural quality continued to attract artists to the area up until the end of 1940s (as detailed in an excellent little booklet written by the curator and printed by the Society to accompany the current exhibition). Yet this was all housing, private and domestic affairs, at most invite-only salons. It seems that the Arts and Crafts promotion of craft skills and activity amongst amateurs in the form of small craft societies was absent in Heidelberg.

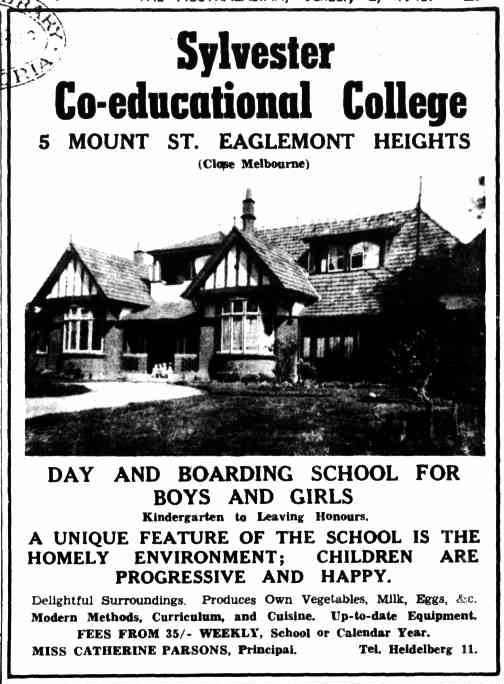

While outside the remit of the current exhibition, something of this spirit was undertaken by the obscure efforts of the Sylvester Co-Educational College that was housed in a large Arts and Crafts manor at the top of Eaglemont. Established in 1934 by Katherine Parsons as an avowedly “progressive” school, the school rejected the rigid instruction of prevailing education models and promoted self-expression and development of the child’s “true self” via a broad curriculum of arts classes, also practising some sort of direct democracy amongst students.

Parsons extended the school’s mission in 1946 as the Sylvester College Free Cultural Centre, possibly the first complete arts and culture centre in Melbourne (as distinct from a specialist craft organisation, gallery space or exhibiting society). The centre hosted exhibitions of student and members’ work, music recitals, film screenings, and held open classes in pottery, painting, photography and writing. Parsons, who taught the pottery classes, was also a member of the Australian Ceramics Society (a founding member of the group being art potter Marguerite Mahood, an associate of Pate and the Wallers during the 1930s, and another link between the earlier Arts and Crafts principles and later artistic developments).

After the Free Cultural Centre faded out, Parsons’ interest in self-development continued when she embraced Scientology in the mid 1950s. She began applying Scientology-derived practices as part of the school’s curriculum, presumably including Dianetic auditing sessions with the use of E-meters. The school’s original mission of promoting the child’s true self would have resonated with the principles of Dianetic therapy. Coincidentally, Scientology, at this point prior to its conversion into a religious group, promoted amateurs to form into small associations who collectively skilled themselves in the therapeutic principles of Dianetics. This would provide each member of the group with an equal role as therapist. While this might seem far from the exhibition (Googlemaps tells me that Sylvester College was only an eight-minute walk from Chadwick House), the move of the school into this therapy model does reflect a very twentieth-century understanding of medium. The Arts and Crafts principles that sought to improve the design of objects crept toward the design of self. It is here that the maxim of Truth, Beauty, and Utility begins to take on a somewhat more familiar and ominous meaning.

Jarrod Zlatic is a writer and musician from Melbourne