JR and Alice Rohrwacher, Omelia Contadina and Homily to Country (2020) at NGV Triennial

Giles Fielke

The procession enters the field, called forth by a clean-shaven, elderly man with thin lips who is wearing a black cap, white shirt and a black jacket. Around fifty Italian farm workers and musicians sombrely walk to surround a pit cut into the ground by a big yellow excavator. The giant black and white effigy of a living contadino is ritualistically buried while the onlookers gather and stare directly at the camera. A fugue plays and the band appears in shot. Speaking their local dialect, the farmers read out excerpts from the writings of Pier Paolo Pasolini and Rachel Carson, the “scientist poet of the sea”. I watch all this occur while seated in the Grollo Equiset Garden at the NGV.

The ten-minute short is titled Omelia Contadina (2020), which translates literally to “Peasant Homily”. It is a collaboration between the Italian filmmaker Alice Rohrwacher and the French artist JR. Omelia Contadina is currently on display alongside JR’s Homily to Country (2020), a project featuring an installation of stained-glass windows depicting Australian farmers and First Nations traditional owners for the NGV’s second Triennial in the same part of the courtyard where Yhonnie Scarce and Edition Office had shown their award-winning architectural commission, In Absence, in 2019. Omelia Contadina is also available on JR’s YouTube channel, where it was published on 16 November 2020. The film premiered out of competition at La Biennale di Venezia film festival in early September 2020.

JR describes the work as a “cinematic action”, that is a kind of collaboration with the inhabitants of the Alfina plateau, an agricultural commune in the Lazio region of Italy. The small town of Acquapendente is nearby—it is two-hours north of Rome by car. Most of the action is shot from above, utilising a camera attached to a drone. “A silent spring will prevail”, someone reads Carson at the pit. The funereal imagery seems intuited and follows Catholic conventions of respect for the dead: mourning, black clothing, eulogy. The “peasants” here are present for their own funerals, and it is “big business” who is to blame for the loss of biodiversity in the region and their livelihoods. “You buried us, but you didn’t know that we were seeds”, warns the final contadino.

At the end of the film, another short video on the making of JR’s Homily to Country begins, expanding on the commission given to the artist for the Triennial. Both short films are ostensibly the same “actions” about industrial monocultures and the related effects on traditional ways of farming and agriculture. In her director’s statement at the Venice Film festival, Rohrwacher writes that as “the daughter of a beekeeper, I told (JR) about the great death toll of insects this causes, and the small-scale farmers’ fight to stem this flood of speculation, subsidies and pesticides”. I can’t help but think of Ernst Jünger, the German war veteran, writer and entomologist who was also curiously invested in mass-insect die-off after the Second World War. Jünger was not so much concerned about the human genocide of the Third Reich, however. This erasure of human subjugation has also recently developed in the work of Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing—and incisively critiqued by Janae Davis Alex A. Moulton, Levi Van Sant and Brian Williams. Vegetarianism was also a Nazi thing, as Morrissey has found.

This is important for how we interpret the work in its combination with the burial scenes in Omelia Contadina. Put bluntly, the combination strikes me as distinctly fascist. The “blood and soil” iconography of burying human “seeds”, the Contadina, is disturbing not only for the fact of the living participants directed by the star artists but also for their belief in their toil as justification for their ownership of their land. Notoriously, this was the basis of John Locke’s “mixing labour” theory of the acquisition of land that was used to justify dispossession in the colonial era. And as Jeff Sparrow writes in his recent book about Australian political extremism, Fascists Among Us: “Nazi theorists such as Richard Walther Darré asserted a semi-mystical link between the German peasantry and the land on which they toiled”. In the Italian context Anthony White writes “that ‘the age of Fascism’ began well before Mussolini’s rule over Italy and has cast a long shadow over that country since the end of World War II”.

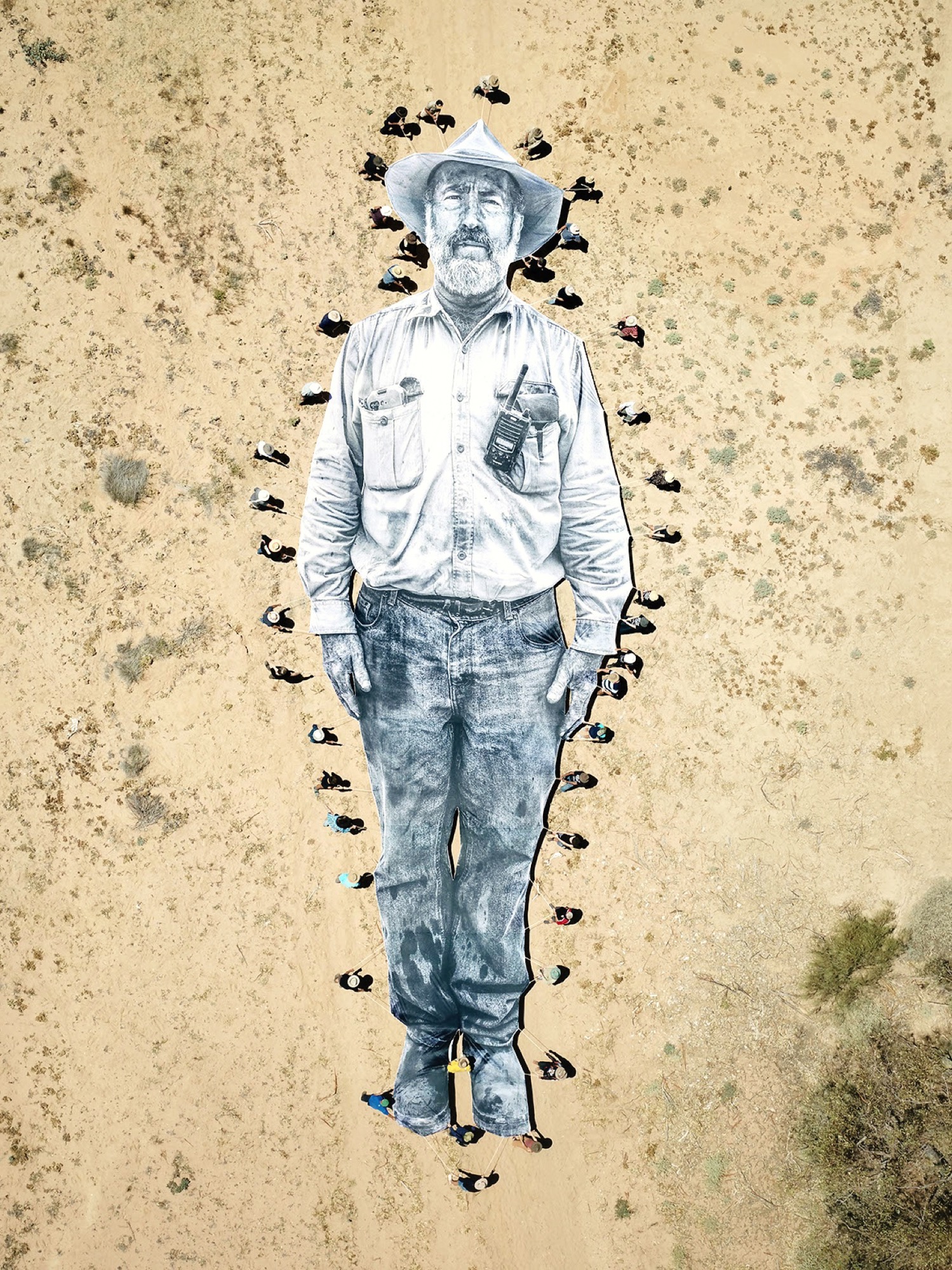

As JR has iterated the project and translocated it into the Murray-Darling Basin, it is this Australian context that I found most troubling (after all, contemporary fascism is a well-known feature of the Lazio region; one look at its football ultras, known as the Irriducibili, will be enough to convince even the most sceptical). Terra nullius encroaches upon the colonial landscape. This raises some very serious questions about the work insofar as it fails to consider the colonial expropriation of the country and its resources—of the Baaka, the First Nations name for the Darling river. Still, the most prominent character in Homily to Country is William Badger Bates, artist and Baakandji elder. But it is the broader implications of this type of work, a collaborative “action” between a European art-star and a local elder artist amongst others—the dynamic tipped in the favour of the younger European artist as the protagonist of the work—and its subsequent realisation of an “open-air chapel”, casting Bates as the saint of the Baaka, alongside “two orchardists who have been forced to remove and burn their families’ commercial orchards”. This is how Margaret Simon describes the work for The Monthly:

Rachel Strachan is there in her sleeveless cotton shirt and frayed denim shorts, socks rolled over battered boots, her hands by her sides with the fingers slightly splayed—as though itching for something to do. Her neighbour, Alan Whyte, is shown with a petrol can in hand and a giant bonfire behind. He was burning his ploughed-up vines and fruit trees. Badger Bates is there, also framed in flame, his gaze direct, accusing and bottomlessly sad.

The portent of anthropogenic destruction is powerful. Yet no distinction is made between the settler colonial figures and the First Nations representative here (although this time around nobody is “buried”). Today the Baaka is flowing again. This is not represented in the work at all; the Murray-Darling Basin plan is the stuff of political nightmare. Signed into law by the Gillard government in 2012, the plan is famously concessionary and did not include any climate change science for reasons of political expediency. Some are now predicting the Menindee Lakes, site of the fish kills in 2019, will be full later this year, after the recent flows from the north. The drought has broken.

It is challenging to say anything meaningful about the totality of work displayed in this year’s edition of the Triennial at the NGV. In fact, that challenge of meaning must be considered a deliberate trade-off when mounting a survey of contemporary art so vast and complex that it belies coherence, and yet it is precisely the challenge set by long-established survey exhibitions of contemporary art like Documenta. Yes, anthropogenic climate change is real: it is visible, and we have been destructive. Yes, inequalities exist. But here I take JR’s Homily to Country project and its antecedent in the film with Rohrwacher to be a synecdoche for the Triennial itself. As French legal historian Yan Thomas has written on commercial and religious definitions for burial in ancient Roman law: “funeral images were conceived to be an integral part of the body”. Here the gallery is a sepulchre.

Others have written about the festival at large. My focus is the relationship in the image between the farm workers and the body politic. This relation may be approached in the same way Thomas excavates it in Roman antiquity, as “not at all metaphorical, but (as) bound to the body by a metonymic relation of part to whole”. As I begin, I am thinking of the Salon realism of Gustave Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans (1849–50). It depicted a moment of the Second French Empire and connected the people to the glory and power of poverty as opposed to pomp, much like JR and Rohrwacher have set out to do today.

My starting point is Rohrwacher’s Lazzaro felice (Happy as Larry). It was one of the best films of 2018. In fact, her first three features are all key works of devotional cinema of the past decade, dealing with the medium itself through the lens of mystical religious fervour and blind faith. While Lazzaro felice imagines a persisting feudal village cut-off from contemporary life and surrounded by the Italian Badlands, still lorded over by a despotic aristocratic family turned sharecropper industrialists (think of Luchino Visconti’s The Leopord (1963), but in reverse), JRs interest in “townsfolk” as the contents for his artwork is a jarring leap for Rohrwacher, the director of Miu Miu ad-campaigns and delicate works of cinema. So, while I genuinely admire Rohrwacher’s films, I can’t understand what it is that makes JR appeal to her, and even to the late, great filmmaker Agnès Varda, with whom he made the 2017 film Visages Villages (Faces Places) in 2017. Perhaps it is simply his popularity. In 2011 he won the TED Prize; Jamie Oliver had won it the year prior.

The NGV website explains to us that “JR exhibits freely on the streets of the world, where he pastes huge portraits of anonymous people”. The obvious problem with JR’s campaign to recognise anthropometric climate change as a question of dispossession is that in Australia the spectre of apartheid colonialism, racism, and the continued program of dispossession of First Nations people continues unabated. We only have to glance at the water sales scandal involving current Government Minister Angus Taylor, from his former involvement with Eastern Australia Agriculture: the expropriation of the country to a Cayman Islands tax-haven is happening right now. If the Baaka and eastern rivers are flowing again, the image of drought-ridden plains is anachronic, in that we predict they will shortly be emptied for a profit.

It is not the return of Nazi’s we should be concerned about; rather, these works suggest a new fascism in our own government representatives, alluded to by Pasolini as the kids sipping Coca-Cola and smiling through their teeth at you. That is, before he was murdered in 1975. The kids he was describing are Taylor and his ilk.

The sovereignty of so-called Australia is, and always has been, in a crisis of settler-colonial making. The NGV’s curatorial intent is for us to see a work that takes the present ecological crisis brought about by the mismanagement of the Baaka by settler-colonists as a synecdoche for the greater crisis of Australian nationalism. That the work is by a contemporary French artist and Italian filmmaker, JR and Alice Rohrwacher, showing at the “National” gallery is perplexing, to say the least. Watching Omelia Contadina, I envisioned the interred generations not so much sowing, as poisoning the soil. Entropy, not progeny.

The first descendent of my family to settle in what is now ostensibly the A20 highway off-ramp heading north-east of Adelaide was born in 1835 and emigrated from the Kingdom of Prussia in 1857. At that time, land in the region was sold as prime for pastoral development. Beginning in 1860 my ancestor had thirteen children, four of whom died in infancy. Johann, born in 1876, lived until 1965 just two decades before I was born in Adelaide. Descendants of my family still farm the Murray River land further to the east, although today it is not so much an agricultural boon as it is a decimated and over-salinated expanse hurtling towards desertification. There is no legacy of colonial ownership or custodianship of the land that is not about exploitation. As Bruce Pascoe has noted, the introduction of hooved animals, grazing in ways unseen prior to 1788, changed this country forever. Ernestine Fielke was born a year before the colonial government in South Australia was proclaimed in 1836.

Auf Vorposten (1815) is a painting by Georg Friedrich Kersting that depicts three rangers, including the artist’s friends Ferdinand Hartmann and the writer Theodor Körner, who fought with the artist and died in the Napoleonic wars. The seated man in the foreground bears the Iron Cross on his chest. As a symbol of Prussia and later the German Empire, it is the identification of the body of the soldiers and the forest that constitutes its appeal to a growing nationalism. The artist’s friends at the checkpoint are protecting the country, presently under attack from Napoleonic forces. The Iron Cross dangles in a full-frontal presentation as a symbol that also guards against invasion in the nineteenth century. It will come to represent fascism in the twentieth (in 1939 it was adapted to incorporate a swastika in indelible relief at its centre).

The Iron Cross has continued to travel through time, re-emerging in the realm of advertising—where most symbols simply sublimate branded identities. It is used in the logo of the Independent Truck Company, a skate brand based out of California. And while these symbols change their meaning, the latent power of the traditional form remains, in some respects to be re-awakened by corresponding contemporary events. The Independent Truck Company was established in 1978 in Santa Cruz, California.

But some symbols, like blood, operate on another level. They are integrated into everyday life as elements for being. Like the Science Gallery’s inaugural exhibition, Blood: Attract and Repel, which opened at the University of Melbourne in 2017, and in a building named for a eugenicist academic, the return of these potent symbols is a signature of our present moment of uncertainty. This year NGV’s curator Simon Maidment will join the Science Gallery curator of Blood, Rose Hiscock, as Associate Director of Art Museums at the University.

Following the events surrounding Spanish artist Santiago Sierra’s commission for MONA this week, I spoke with a friend whose father is an academic. His job now involves flying around Australia, working to repatriate blood samples taken from First Nation’s people by university science departments and kept since they were taken mid last century. It is a project that has been covered in the journal Nature and indicates the willingness of research-institutions to right the wrongs done by institutions in the past, that is the privation of a part of the body for science. But what happens when this science seeks representation?

The NGV and MONA are in direct competition for visitors and cultural tourism. “MONA is everything a state art gallery is not”, writes Matthew Westwood recently for The Australian. Of course, this makes it all the less surprising to hear that the NGV has acquired a state-of-the-art sound-system that is the very same design as that in use by MONA (estimated to have cost over $100K). State art gallery directors like Tony Ellwood not only dream of the kinds of subversion private institutions get away with they covet their toys too. There is a further link here to be made between institutions like the La Biennale di Venezia and Triennial: the prestige of institutional cooperation and power. The “collaboration” by JR with the Baaka community repeats the larger administrative collaborations that carry on above. This is the aesthetic of participatory or “activated” art.

Political extremity has been described as a “horseshoe” shaped spectrum whereby the opposing edges of the so-called “Overton window”, what is deemed politically viable discourse, are closer to their opposing ideologies than the centre. First Nations activists and critics, social justice campaigners and parliamentary culture warriors like Eric Abetz (whose great uncle Otto Abetz was an SS Officers and the German ambassador to Vichy France, and whose grandfather Karl Abetz was a professor of forestry science, who joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and became general consultant of the Reich Forestry Office) stood side-by-side in condemning Sierra’s blood performance work, Union Flag, programmed to take place during this year’s Dark Mofo festival at MONA. The work called for “collaboration” with First Nations people subject to British imperialism by requesting that they donate their blood to be soaked into a Union Jack flag. On 23 March, MONA’s curator Leigh Carmichael put it simply: “proceeding isn’t worth it”. A day later, prominent Tasmanian Aboriginal leader and chair of the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania, Michael Mansell, spoke out against the “censorship” of the incendiary Spanish artist and his work, an act he thought validates Tasmania’s colonial-practice of hiding its bloody truth.

But this division threatens to over-simplify the issue, for or against. Murdoch’s monarchists and First Nations’ curators like Yorta Yorta woman Kimberley Moulton, lined up to condemn Sierra’s proposal for different yet corresponding reasons. “Blood is sacred”, wrote Moulton on Dark Mofo’s Instagram post announcing the project. The Australian framed it as a “two-fingered salute to Britain”. Artist Brook Andrew said he does not believe in censorship of artworks but does believe in the philosophy of yindyamarra, which means taking life slowly and with respect and care (broadly, “duty of care”). That they form some kind of uneasy coalition against MONA in this instance speaks more to the ability of Sierra’s re-alignment of somewhat clichéd political lines from the perspective of an outsider and his presentation of discourses on sovereignty is surely intentional. Its conceptual component has already “happened” so to speak. (A number of critics of the work are also at pains to point out that Sierra is Spanish and so his own nationality means he is entangled with fascism. True—but aren’t we all complicit here?).

Strangely, within a week Victoria’s Chief Health Officer, Brett Sutton, called for urgent blood donations in order to bring supply back to normal measures. MONA’s misguided intervention into blood rituals and First Nation’s sovereignty may have set back the science for years to come. Indeed this is the blind-spot of the eco-fascist narrative that Sparrow writes on in Australia. For example he refuses to note that when murderers like “Person X” (the term for the Australian fascist Sparrow focusses on in Fascists Among Us, his anatomy of the Christchurch massacre) and his copycats—like the Poway, California murderer, or the Walmart shooter in El Paso—apply the term “invaders” to people they perceived as illegitimately occupying “their” territory, the most obvious analytic is that they are failing to recognise themselves as invaders, as colonial “settler-occupiers” on land that has never been their own. In many ways these men were yelling at themselves as they targeted people going about their lives in peace; shopping, praying, or studying.

The result of all this is that, I would argue, the NGV (and MONA for that matter) should seriously consider what it means to show these works of film and video, these “actions”, and what it means to turn them into installations. The way to do this is to devote genuine resources to the collection of works on films and to the better understanding of the aesthetics of the apparatus. Currently, the NGV refuses to collect art on film and so condemns itself to institutional ignorance. Its excuse is that’s ACMI’s job. How is that an acceptable response when it comes to the politics of display in a public gallery? If the NGV is going to continue to show works that are informed so closely by the histories of film, it must be compelled to understand them. The salon hang is not a thing of the past; it has been dispersed and is now called a festival or a Triennial. The aesthetics of fascism recur in public art galleries when the curators and management are not interested or concerned for the visual component of the work but only its “content”.

Lastly, JR’s work is also a symptom of “Design Thinking” taking over the spaces and places for art. The entryism and attempt to normalise street art as academic art in recent times—KAWS being the most obvious example—was described earnestly by the gallery as the artist navigating “the complexities of modern life” by bridging art and design. “Internationals”, including Sierra and JR etc., don’t nearly understand well-enough the intense and considerable politics of representation in so-called Australia today. They fail to understand the local complexities almost as the predicate of their respective practices. And so it is no surprise that the curatorial staff looking to “import” cool or edgy (read as “avant-garde” although JR and Sierra is neither) art into Australian cultural institutions have absolutely failed to read public sentiment here, when international arrivals have been postponed due to the pandemic. That is their cross to bear; design thrives in a de-contextualised environment.

This is not to say that design is unimportant, nor that it should not be considered as art. But disegno, a term Vasari used to refer to “drawing” in his Lives of the Artists, is not just one of the arts, but the father of all the arts. Design’s attempt to replace painting in the hierarchy of art only reinforces it. Instead, we should be able to have more space for a plurality of arts practices. Yet these false binaries and bad-faith competitiveness of the arts “which eat away at each other”, as Theodor Adorno said, can be effectively dealt with by gallerists and curators by thinking of the politics of presentation. Sure, but also by limiting what it is they believe what they are doing. How does one draw a line around an exhibition like the Triennial? It is very hard because the curatorial remit explicitly denies one from doing so.

“Design Thinking” is a course now offered online by Monash University, in the faculty where I work. Many younger artists I’ve spoken with use the trope uneasily to mean that they feel encroached upon by this new disciplinary theory. In some ways, this sentiment speaks to related fears of replacement by another. The sowing of these fears—that resulted in mass-murder in Christchurch—get instrumentalised by new media wackos like Sky News contributor Lauren Southern whose program is to openly hate anything that is not part of their own narrowly-defined idea of “modern-life”. All of this is related to the divide and conquer component latent in capitalism, and predicated on scarcity producing competition. We may be image poor, but we are not short of the resources we need to resist this banality. I’m thinking now of Vernon Ah Kee, artist and founding member of ProppaNOW, speaking to the public: “we are all racists”, he began. We are also fascists. What are we going to do about it?

Giles Fielke is a writer and researcher of artist film.