Tracey Moffatt: Body Remembers

Rex Butler

The shadows are the first thing you notice. They’re uncanny, haunting, impossible, technological.

Take Spirit House (2017), which has the one remaining wall of an abandoned limestone building—we are tempted to call it a mission church—casting its shadow under a cumulus-cloudy sky. It’s an impossible shadow because deep within it the tops of the grass stalks keep on glowing, the light from the two doorways faces in opposite directions and in one of these the shadow of a figure that is otherwise absent stands. And if we look even more closely, at the edge of the shadow at the front a strange glowing orb appears like a small displaced sun, matching the brilliant glint on the top of the roof.

Or take the clothing line of shadows strung together in Washing (2017), with the maid that the rest of the series otherwise depicts desperately trying to peg to the line a shirt whose arms wave demonically in the wind and a puzzling diagonal line running up the surface of the building, which again we sense is abandoned. The figure of the maid strikes us as wraith-like as the shirt and she appears herself pegged to the line, and just as liable to blow off into the empty field behind.

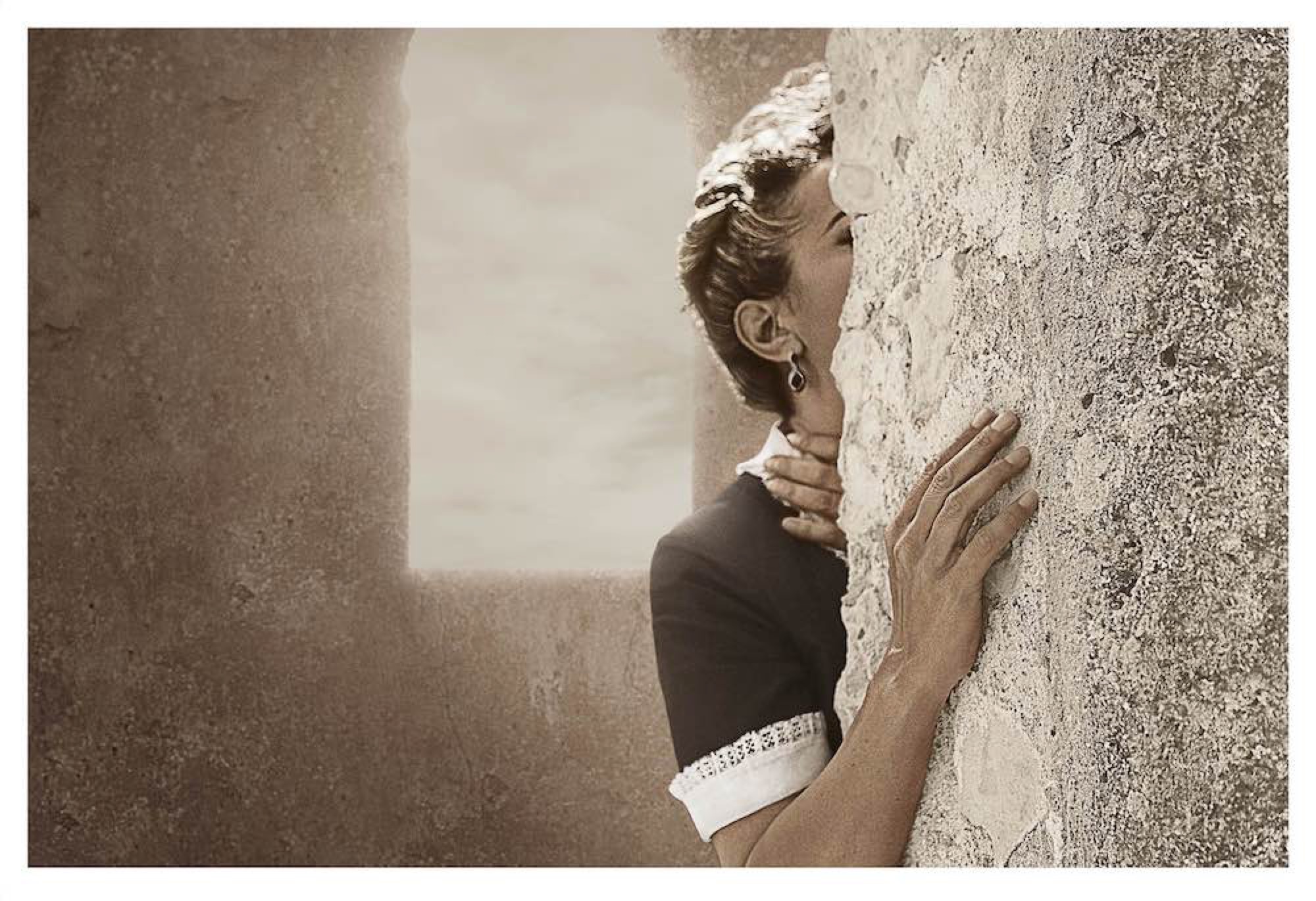

Or finally there is the silhouette of Shadow Dream (2017), cast against a lichen-encrusted wall, maid-like in the hands crossed dutifully behind her back, resistant in the tilt of her chin and thrown-back shoulders and with her hair blowing in the wind staring into the distance. It too is an impossible shadow, because where could this figure be standing to cast a shadow like that without also being in the camera’s frame? It’s, of course, a ghost, disembodied, wistful, as old and ingrained but also somehow as indiscernible as the lichen onto which she is cast (and the lichen in the cracks of the wall can only itself be seen within the figure’s shadow).

All of these images are from Tracey Moffatt’s by now well-known series Body Remembers, made for her exhibition as the Australian representative at the 2017 Venice Biennale—and the shadows are doubly haunted because not only do they stand in for the maid in black and white uniform that we see from the back in other images from the series, but also for the iconic and instantly recognisable figure of Moffatt herself, who plays the maid.

Body Remembers is said to be about Moffatt’s great grandmother’s experience working as a cook and domestic servant on a remote cattle station in Central Queensland in the early twentieth century, a great grandmother Moffatt never knew and who undoubtedly laboured in conditions of effective indenture in Australia’s colonialist past. But Moffatt’s point in this series is that the present is always haunted by the past, that the sun of a new enlightenment is unable to erase the shadows of what has been, which persist ineradicably, a little like the data stored on the discs that make up Moffatt’s computer-generated photographs.

Nevertheless, one of the strengths of Moffatt’s work is that she acknowledges that this past also makes her up, that she in her own inner life shares these same memories or even fantasies of indentured servitude as something that gives her her own identity. In the two series of Scarred for Life (1994 and 2000) she re-imagines incidents from her own childhood, in Pet Thang (1991) she photographs herself dreaming next to—of all things—a sheep, that emblem of white Australian national identity (imagine hanging Pet Thang next to Shearing the Rams at the NGV one day!), and in Laudanum (1998) we have something of the same scenario of a servant in a seemingly abandoned house.

Like all of us, in other words, Moffatt is haunted by ghosts—personal, familial, cultural—which divide us, split us, for all of our attempts to gather ourselves, fix our collars, smooth our hair, shape the way we appear to others. Instead, we are always opened up to the ruined buildings and permanently blazing fields of our and others’ pasts.

What is the maid of Moffatt’s series doing, alternately posing sensuously against the wall, holding her head in anguish, gazing nostalgically out of a window, holding a hand pensively behind her head, leaning absently against a doorway? We are looking in this series at all of the small moments that make up a life, those otherwise lost and passing incidents that will remain when we too become ghosts. I look at the brown and slightly aging hand of Touch (2017) as it reaches out towards me and I am touched. I could stare at it forever. It is beautiful.

Curator Anthony Fitzpatrick, inspired by a number of the pages of the catalogue for Venice in which Moffatt lists her cultural and artistic influences, has put together an accompanying exhibition entitled Thought Patterns, featuring works from the Tarrawarra collection thought to bear some affinity to Moffatt’s work.

In perhaps some measure of the universality of Moffatt’s practice and how it might refigure the notion of the “Australian”, we have paintings by Joy Hester, Charles Blackman, Louise Hearman, Gordon Bennett, Judy Watson and several by Russell Drysdale, whose work was the inspiration for the series that first brought Moffatt to attention, Something More (1989). Perhaps the Drysdale most resonant with Body Remembers is Basketball at Broome (1958), which features a white-frocked nun playing basketball with a group of young Indigenous girls, undoubtedly on a mission. (Drysdale travelled through the Kimbereleys in 1956, painting amongst other things Malay pearl divers and Broome’s Chinatown.)

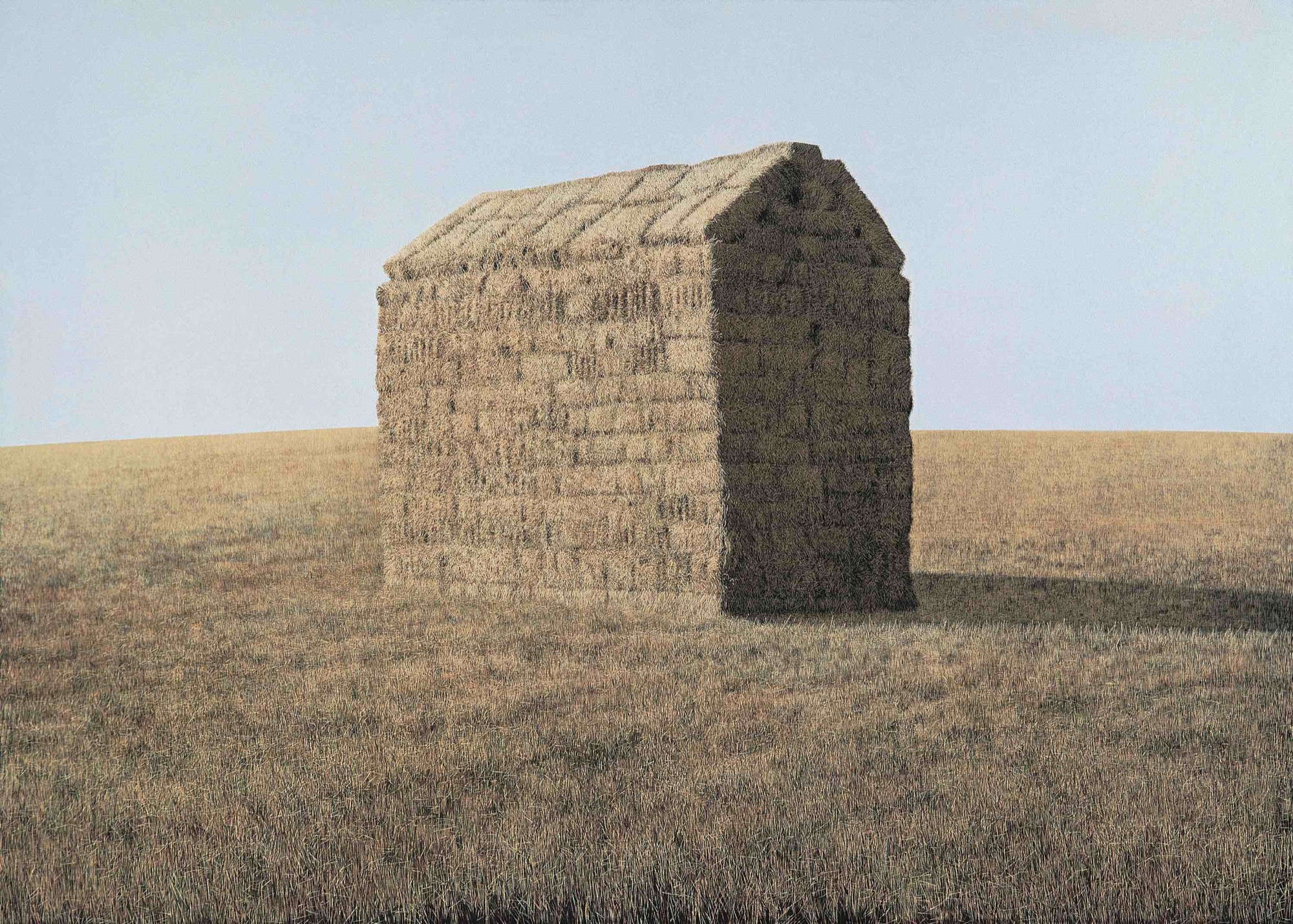

But the unexpected connection to be seen is with the largely critically overlooked William Delafield Cook and his A Haystack (1978), which has the same translucent shadow as Moffatt’s series, and we can even pass from Delafield Cook – as the Queensland Art Gallery has done in the new hang of its Australian collection – to the Rosalie Gascoignes in Fitzpatrick’s selection, with their boarded-up wooden panels that somehow strike you as like the abandoned church with its missing windows of Body Remembers. And, indeed, the decrepit walls of Moffatt’s church can even be seen to match the slightly Brutalist concrete driveway and entrance of the Tarrawarra Museum itself.

Also at Tarrawarra is another of the works from Moffatt’s Venice show, Vigil (2017), one of the video pieces featuring found footage that Moffatt has been making for the past twenty years. In some regional gallery or metropolitan cinemathèque, most art audiences have seen a selection of the works Moffatt produces with film-maker Gary Hillberg with names like Artist (2000), featuring clips of artists variously making or destroying their work, or Other (2009), showing Western cinema’s depiction of other races.

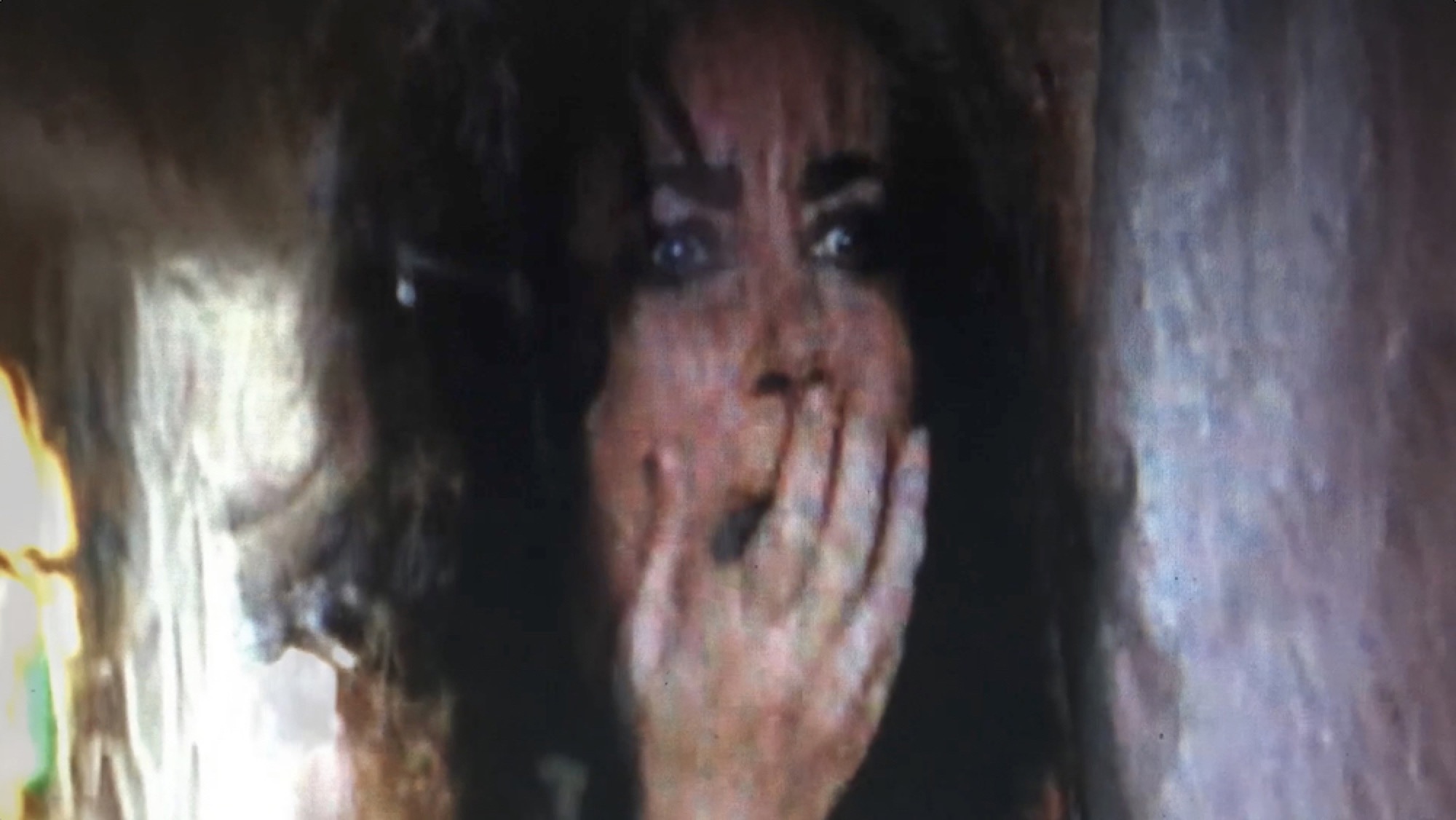

Again, Moffatt plays both on and against this brand recognition on Vigil, which depicts a series of moments from Hollywood films in which characters either stare out of windows or hold binoculars up to their face – Cary Grant in North by Northwest (1959), Julie Christie in Darling (1965) and Donald Sutherland in Day of the Locust (1975) – but this time intercut with footage of an asylum seeker boat crashing into rocks and throwing its occupants into the water.

As the two-minute sequence proceeds, the faces of the stars in their otherwise unrelated scenarios grow more and more agitated, until by the end we have repeated shots of Elizabeth Taylor in Night Watch (1973) gasping and throwing her hands up to her face in response to what is going on.

It’s an ingenious piece of editing because it suggests, first, that we always leave our responses to asylum seekers to others, allowing them to look and act in our place in a textbook example of interpassivity, and, two, that all of Western civilization, including its Hollywood entertainment complex, is built on the exclusion of others.

And, third, it’s appropriate to do this in Venice, a city surrounded by water and in a country that exactly at the time Moffatt was showing her work was having its own immigration crisis with Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni trying to strike a deal with Libya to limit the number of refugees crossing the Mediterranean. And this interpassivity – the way increasingly in our society we leave it to others to witness and respond in our place – is precisely what allows us to react with compassion to what Moffatt shows us. If Elizabeth Taylor breaks down in tears, then we don’t have to. If Tracey Moffatt makes a work about refugees, there is nothing more to be done.

Art in these circumstances remains poised between an incitement to action and the excuse that by experiencing something aesthetically we don’t have to do anything about it. Between something that reaches out across boundaries and the accusation that this is not how anything gets done any more. Art is at a tipping point today and, like those asylum seekers on the boat, we are all about to get thrown into the perilous seas of the unknown. That day when I was standing in the gallery in Tarrawarra, only Moffatt’s hand stretched down to save me.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.