Ruth Höflich, To Feed your Oracle

Ursula Cornelia de Leeuw

In the heritage listed mansion that is Linden New Art gallery a new exhibition from the Munich-born, now Melbourne-based, multidisciplinary artist Ruth Höflich is on show. Its title, To Feed your Oracle, gestures toward the mysticism of its forms, requiring an informed eye to sift through its contents and extract whatever prophecies they may tell.

The show begins in the front of the house, arranged around a centrally falling curtain that divides the room into two. Made from colour-blocked fabrics in royal purple, blue, black, white and stage-red, the curtain (Traveller, 2021) is also split in two parts so that objects may be glimpsed in the space between its folds. In this gap rests an aluminium tray standing on four coaster feet, implying the possibility of movement between the two sides. On the tray are a selection of archival pigment print photographs layered on top of one another, as if they were freshly pulled from a filing cabinet. These coaster-trays are repeated around the room with different images atop them and are individually titled: Table with green light (2021), Table with red light (2021) and Table with eyes to look through (2021). In the act of viewing, one is forced to stand over the work, peering down into its depths.

These photographs that, as we are told, are eyes through which we may see, appear again on the gallery walls as three more archival pigment prints encased in aluminium frames: Eyes to look through 1 (2021), Eyes to look through 2 (2021) and Eyes to look through 3 (2021). Across the series, abstract forms are depicted in vivid colour as well as black and white, a few of which can be made out: the texture of a leaf (or is it some other veined surface?), a spoon floating in a strange space and a red blotch against a pink background with what appear to be fingers reaching for it. There are also two more photos that appear aesthetically excluded from the rest: a pair of unframed black and white prints, the first of which depicts a balloon held over the flame and the second showing the page of a binder (which is actually a screenshot of a Word document) laying atop a pile of other documents. They are titled The ceiling, the floor, the walls 1 and 2 respectively. Perhaps these outlying photographs are the frame, or the bones, that are key to the room, while the other pre-framed photographs gaze with mystic eyes, and flash their lights at the viewer. It is the obfuscation of their subject that echoes throughout these photos, not only in the way they are the result of certain aesthetic considerations, development processes and installation plans, but in the way they embody the complexity of the archival abyss itself.

The exhibition was conceived as Höflich undertook the Georges Mora Fellowship at the State Library of Victoria, where she mined the WG Alma Conjuring Collection: an archive of magician’s materials collated in the 1960s and 70s by Australian magician and manufacturer of conjuring apparatus William George Alma. The collection contains 2000 books on magic, 60 magazine titles, 1500 photographs, 300 posters and over 400 detailed research files on individual magicians. However, Höflich said she mainly looked at the archive’s visual material such as sets and props, or as she put it “ephemera surrounding the staging of magic”. It is this element of staging magic that is clearly emphasised in the concept of the Linden show. When Höflich was initially congratulated on the fellowship by Art Guide back in 2019, it was reported that only magicians could enter the collection. However, it seems that Höflich has been able to infiltrate the illusionist’s inner sanctum and point toward the magician’s manipulations.

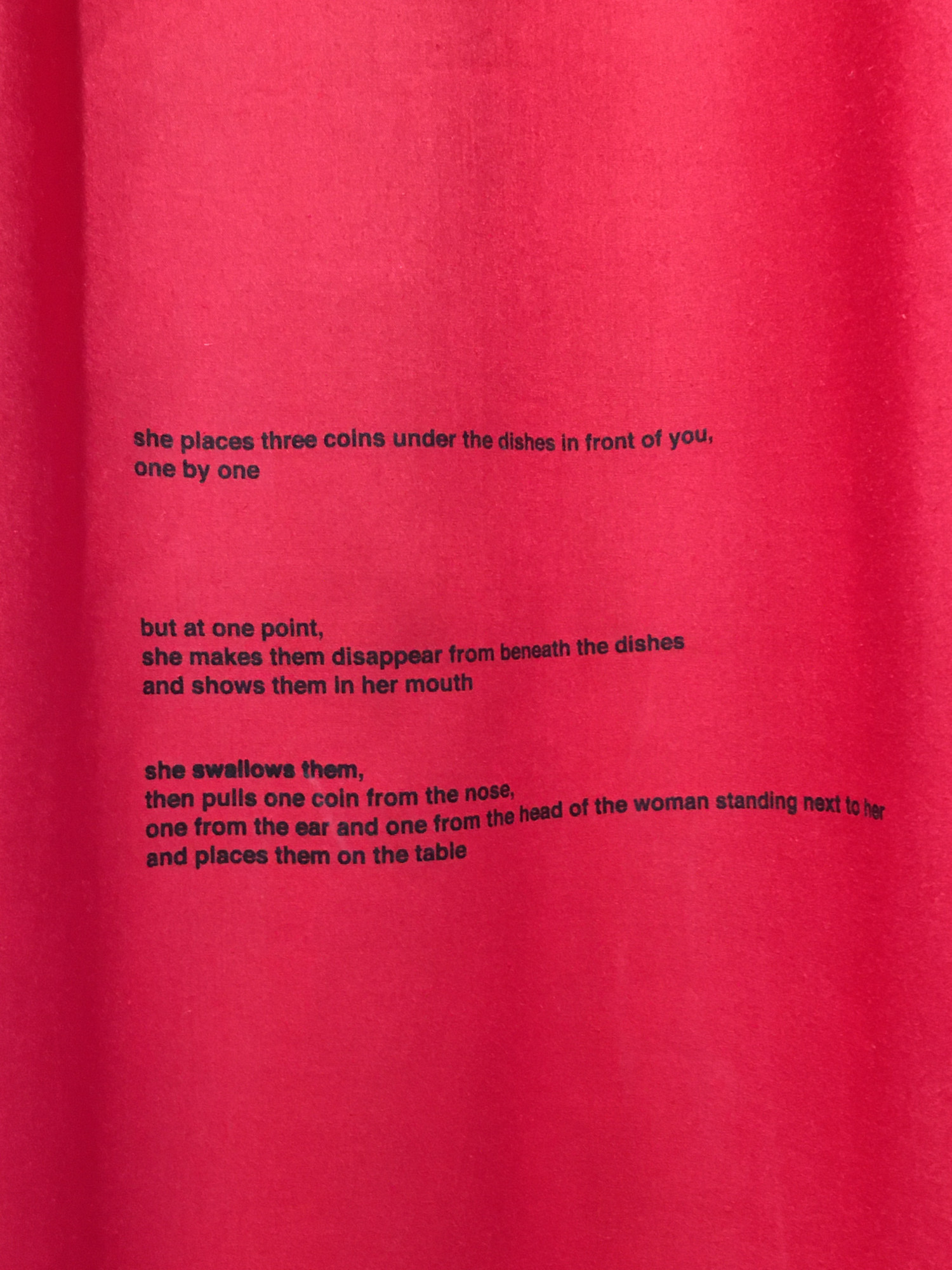

In the exhibition catalogue, an interview with Höflich illuminates a photo for us: it depicts a trick whereby a balloon is held above a flame, but does not burst because it is filled with water. Höflich emphasises that this is not really a trick at all, but a scientific phenomenon to which most audiences are uneducated. Thus, Höflich indicates that “the trick” is usually but a natural process wrapped up in the spectacle of magic. There is an implicit critique of the magician’s sleight of hand here, repeated as Höflich critiques the manipulative gender relation between the magician and his female assistant traditional to the history of magic. This is reversed in a poem printed on the surface of the curtain, wherein a woman magician performs a trick with three coins and three dishes. So, Höflich plays with and, to an extent, exposes the power relations between a magician and their audience. But I am not convinced that the power of magic stops here—at the dispelling of the magician’s spectacle. How could magic ever really be just that, a process to uncover if one had the tools of knowledge? I don’t think Höflich is convinced either.

Höflich’s photographs consist mostly of everyday objects such as coffee cups and table surfaces, imbued with a kind of magical quality in their relation to the install. Moreover, a kind of magic is felt in sifting through an archive itself: Alma’s collection, the files of photographs and the indexical yet obscured archive of memories from her/one’s own life. Regarding her fellowship, Höflich described the magical properties of the library space:

I like the idea of the library as almost having a sort of psychic affect to it in the sense that when you start working with certain materials other unpredictable things emerge. The research sort of has a life of its own; things unfold and present themselves.

In Höflich’s exhibition, the magician is a kind of false prophet. Magic is not beholden to its performer, but arises from one’s environment; from the matter that leaps from materials in a moment of mystic insight. It is assumed that an archive is perfectly ordered, arranged, and filed away for ease of access. However, in the fervour of research this is not the case. Jittery fingers sift through documents with the gut feeling that they are on to something—to what? They are not sure. The experience is more akin to filing through a box of memories, like an aluminium tray filled with blurred images that cannot be made out quite yet but remain unquestionably significant. This notion of a feverish “memory archive” arises in Höflich’s single-channel video, located in a darkened room behind the initial spectacle.

The video also entitled To Feed your Oracle (2021) is part documentary interview, part performance with aspects of poetry, montage, and cinematic narrativisation. The didactic panel tells us that the film is of a group of people recalling a selection of images they were shown prior to filming. An off-screen rendition of Bach’s Solfeggietto plays over these descriptions as well as, at other times, another voice dictating parts of the body. The combination sounded to me like a perversely strict ballet lesson out of a surreal Lars Von Trier film or something similar. The camera shoots extreme close ups of interviewees fidgeting with their hands, clothes and hair as they recall each memory-image, almost like they are being viewed by a protagonist in a movie who is falling in love with every minor detail of them. The recollections are inter-spliced with shots of the group draped over each other in strange positions, as well as shots of wildlife, dirty dishes and close-up textures. The result is almost painfully sincere in its dedication to beauty and a feeling of longing, underscored by drama, mystery and an overall dream-like quality. The seduction of a magical spectacle is felt once again, this time on the stage of memory and cinematic intervention.

I am reminded of the Proustian staging of memory, whereby the consumption of a madeleine cake, described in sumptuous detail, begins the narrator’s romantically tragic voyage to Swann’s Way. The fragments of Höflich’s montage mimic similar flashes of involuntary memory, connecting seemingly unconnected occasions that return to the repetition of images pictured again, and again, by each participant. Due to its indexicality, whether one problematises this relation or not, the camera is often discussed as a relator of memory, especially when used in a documentary style (Thierry de Duve, Susan Sontag). But it is also a master manipulator, altering our means of perception with a deceptive cunning. As memory is unreliably archived in Höflich’s film, and indeed throughout the photo-centric nature of the exhibition, this double-gaze of the camera is felt. Each person travels down a different path of remembrance particular to them, but their individual memories are presented as a collective series of images, wherein the identity of the re-teller is skewed by the mass. While they are individuals, they are part of a network that is given form by the film. Moreover, they are connected by the dream-space of the camera; a conduit to the network’s innervation that exposes its nonconscious desires. However, this raises questions surrounding Höflich’s role as a magician and the potential illusory nature of technological reproduction itself.

When speaking to techniques of re-production such as magnification, Walter Benjamin claimed that photography can “show the difference between technology and magic to be entirely a matter of historical variables”. In Benjamin’s writings, photographs can illuminate the most minute details of everyday life, so much so that they show what is usually kept in the realm of dreams. The difference between magic and technology is technology’s connection to history, to the apparatus itself and the trace of its processes. In her catalogue interview with Linden curator Juliette Hanson, Höflich references deep fakes as an instance of technology merging with magic. She talks about the manipulation of everyday life by the media—the invisible hand of the magician who hides the means of their tricks. If Höflich’s photographs make the everyday magical, further obscured in layers upon layers, she too partakes in this kind of phantasmagoria. The fantasy of the site, of its nineteenth century fittings and fixtures, adds to this illusion. The participants in the film are directed and analysed, transformed into a romantic film that is at once earnest and marvellously manufactured. But this aspect does not problematise the work as much as it gestures toward the impulse to transform that is inherent to magic. The ability to wake up these images from the realm of fantastical dreaming into the real becomes a matter of its exposure; the apparatus must trace its inner workings, its blood and bones, that connect it to the universe. The remnants of process in Höflich’s exhibition, namely The ceiling, the floor, the walls 1 and 2, hint toward this connection. The unframed prints are simply pinned to the wall, and appear to be the only instance where traces of the Alma collection are physically visible. While the rest of the work looks clean and slick, its reflection on the archive, too, is tense against the mastery of illusion that ebbs and flows from it.

As inferred by the title, Höflich’s alternative to the magician is the oracle, typically a woman mystic who is empowered by embodied knowledge. To feed the oracle already implies a body, but what is the body here? The narrativised body of the Oracle who regurgitates a coin and pulls another from a woman’s ear? Or is it the body of the camera, of the technological means of memory-reproduction? Perhaps it is the body of the archive that assumes a strict order, only to leave one falling between its cracks. All these questions go to say that the oracle can still be mischievous, as further proven by the epics of antiquity. And what fun would form-making be without cunning? But Odyssean wit and avant-garde mystery are not the same as an illusionist’s cheap trick, and the artist should usually avoid becoming a con. However, to have a body is to have a base, and to look to the body for knowledge is to receive information from a material, rather than idealised source.

Höflich’s exhaustion of an archive that still maintains artistic mystery shows us that she has reached the edge of impossibility; a place where many researchers go—particularly when investigating forces of the unknown. In this admittance a service is given—there is no “solution” to the hold magic has over us. It springs forth from the process of looking, and the harder one looks the more the material of one’s interrogation transforms this mystery. In this there are endless possibilities, like the reproduction of memories and photographs in copies upon copies. Is this the oracle’s prophecy? Rather than beg any more questions, I leave this review with a reflection. Höflich said in her interview that “the photograph is only the beginning or the surface of something more complex related to the mediated process of seeing things.” This statement, combined with her meditations on memory, reminded me of a passage written by Walter Benjamin in ‘Berlin Chronicle’, a piece through which he recalls places from his childhood that he performs again and again amongst the décor of Berlin. It is as follows:

Language shows clearly that memory is not an instrument for surveying the past but its theatre. It is the medium of past experience, as the ground is the medium in which dead cities lie interred … the matter itself is only a deposit, a stratum, which yields only to the most meticulous examination what constitutes the real treasure hidden within the earth: the images, severed from all earlier associations, that stand like precious fragments or torsos in a collector’s gallery—in the prosaic rooms of our later understanding … Yet no less indispensable is the cautious probing of the spade in the dark loam, and it is to cheat oneself of the richest prize to preserve as a record merely the inventory of one’s discoveries, and not this dark joy of the place of the finding itself.

At the risk of siphoning art into a dense philosophy (and turning this review into a mode of exegetical subterfuge), I will note that this passage speaks to the performance of memory on the stage of image-making. Like a magician on their pedestal, the artist risks conjuring an assumed reality from thin air. The shiny objects in a collector’s gallery enrapture their audience and wrap the world up in a neat little package. As Benjamin declares, to dispense of the probing spade is to cheat oneself of the joy of looking. It is the residue of an image, the traces and instruments that contribute to its making, that communicate its richness to the cosmos. Höflich reminds us of the archive from which the image leaps; the place of its finding in the darkened corner of a library, surrounded by reproductions.

Ursula Cornelia de Leeuw is a writer in Melbourne.