The Picasso Century

Anna Parlane

In a 1988 Sydney Morning Herald article, Steve Jobs effectively summarised his “genius bad boy” persona with a quote he attributed to Pablo Picasso: “Good artists copy. Great artists steal”. Fittingly, the quote is certainly apocryphal—versions of it have also been attributed to T.S. Eliot, Igor Stravinsky and several others—however you can understand why Jobs might have thought it came from Picasso. For well over a century, there has been an entire industry dedicated to supporting the impression of Picasso as the exemplary genius bad boy, whose sheer inimitability simply demolished any prior or competing claims to the authorship of the ideas that appeared in his work. For example, in his three-volume biography of the artist, John Richardson relates how for a period of time Constantin Brancusi refused Picasso access to his studio on the grounds that Picasso would steal his ideas:

“Picasso is a cannibal”, Brancusi said. He had a point. After a pleasurable day in Picasso’s company, those present were apt to end up suffering from collective nervous exhaustion. Picasso had made off with their energy and would go off to his studio and spend all night living off it. Brancusi hailed from vampire country and knew about such things, and he was not going to have his energy or the fruits of his energy appropriated by Picasso.

Richardson goes on to situate himself—with genuflections about his own unworthiness—in the position of those of Picasso’s friends and colleagues who were fed on by the master: “Some of us—myself, for one—prided ourselves on having made a contribution, however paltry, to his work”. Richardson’s book documents in detail how the distress of Picasso’s romantic partners also became fodder for his art. In light of this, his means-ends justification of the artist’s behaviour becomes deeply disturbing. As Hilary Spurling observed in a 2007 book review, Richardson seems to regard the self-sacrifice Picasso demanded of those close to him as “a form of public service”.

That Picasso was a very good artist is, obviously, not in question. That he was frequently a very bad person has also been firmly established. However, it seems that we still need to talk about the monstrous nature of “greatness”, the toxic entitlement of those who believe themselves to possess this quality, and the ways in which the myth of “greatness” is still perpetuated by our cultural institutions. In this regard The Picasso Century, which was developed for the NGV’s Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series by the Centre Pompidou and the Musée national Picasso-Paris and curated by the Pompidou’s Didier Ottinger, has laudable curatorial goals. Rather than pretending Picasso’s work was produced sui generis, Ottinger takes a revisionist approach, aiming to rethink the artist’s work by framing it differently. His introductory wall text promises to demonstrate how Picasso was “an artist in and of his time, absorbing or reacting against the ideas and actions of artists and intellectuals around him”. Despite the blockbuster machinery powering this show and the rhetoric of the masterpiece that frames it, I hoped that Ottinger’s effort to stitch Picasso into his cultural and socio-political context might bring his art into a more human scale, as well as giving due credit to the many others who shaped his worldview and his work.

The fact that the NGV is capable of revisionist art history at its best is exemplified by the Queer exhibition currently on show on level 3. A passionate, exuberant mapping of irrepressible queer identities, queer cultures and queer love across the full historical scope of the NGV’s collection, the exhibition manages to be both epic and intimate, keyed to the specificity of individual lives. However, clearly the kind of curatorial voice that speaks so eloquently in Queer is hamstrung when dealing with an artist of the magnitude of the big P.

As I elbowed my way through the crowds inside the exhibition (four-deep in front of every Picasso work, with phones held aloft and furiously snapping I-was-there pics), the fiery words of first-gen feminist art historians were ringing in my ears. Linda Nochlin’s Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? was written a decade before I was born, but her laser-sharp analysis of how “greatness” is constructed and institutionalised is clearly still relevant. Griselda Pollock’s Avant-garde Gambits, written in 1992, similarly detailed the “self-curating strategies” by which now-canonical artists produced the fiction of their own singular genius. The retro nature of these references gets precisely to my point: my criticisms of The Picasso Century are entirely unoriginal, because the show perpetuates the same problematic model of artistic value that art historians like Nochlin and Pollock diagnosed decades ago. Despite its revisionist goals, in practice this fundamentally conservative exhibition serves, in ways subtle and unsubtle, to re-centre Picasso. Rather than showing him as one artist among many, it ultimately seeks to bring the whole of the twentieth century into orbit around him.

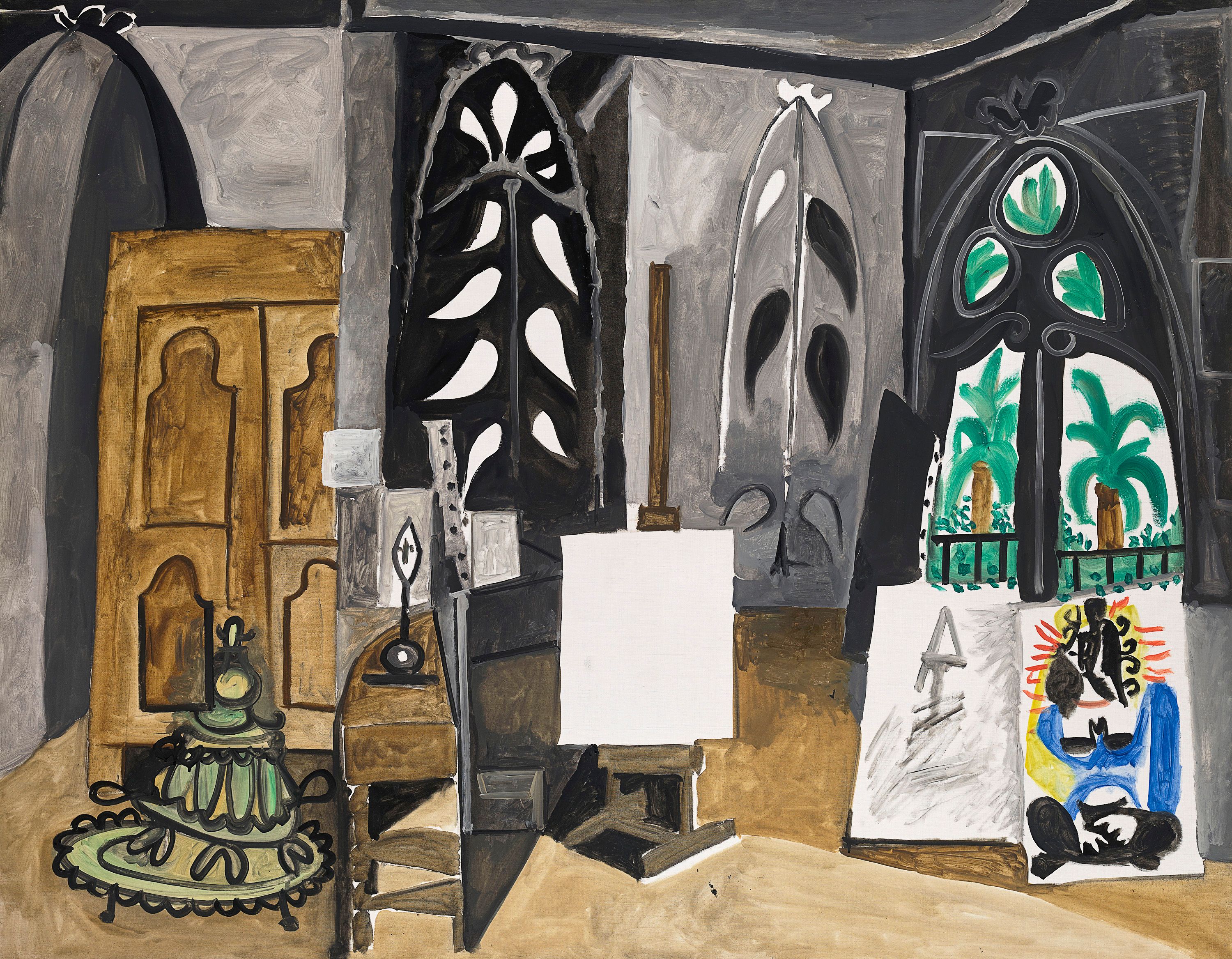

The show sets the phases of Picasso’s artistic development into historical context. The sequence is largely textbook: beginning with the glamourous squalor of bohemian Montmartre, we move through Primitivism, the intense collaboration with Georges Braque that produced Cubism, and into Surrealism. A room with the innocuously formalist title ‘Drawing in Space’, which places Picasso in conversation with sculptor Julio González and early works by Alberto Giacometti, is in fact an exploration of sadistic erotic violence. The pervasive and predictably overt misogyny in the works is legitimised by equally predictable references to Freud in the wall texts. The theme of violence continues with rooms dedicated to the war years, the production of Guernica (1937) and Picasso’s somewhat half-hearted communist phase. While the bulk of the show presents Picasso as a painter and occasional sculptor, a display of ceramics he produced together with Georges and Suzanne Ramié through the 1950s nods to the actual diversity of his output. The exhibition concludes a little flatly with Picasso’s denouement in his later years, a spirited defence of obviously awful paintings like Woman Pissing (1965), and the argument that his influence motivated a new generation of self-proclaimed genius bad boys. We are told that the postmodern and neo-expressionist painters who rode to fame in the booming art market of the 80s saw Picasso as a “kindred spirit” and were inspired by the aggressive energy of his late works.

There are, as promised, numerous examples of the works of Picasso’s contemporaries, and I’m grateful to Ottinger for introducing me to several fascinating artists I hadn’t come across before. The opening display about Montmartre shows us Picasso as a young artist, finding his feet and learning by mimicking the work of others. There’s a curious group portrait by Marie Laurencin showing the poet Guillaume Apollinaire as the centre of a friend circle also including Picasso, Gertrude Stein, the artist and others. Particularly in these first parts of the show, it was also a pleasure to see fantastic works by lesser-known artists like Louis Vivin, Suzanne Valadon and Natalia Goncharova—the latter is an artist who surely deserves her own exhibition.

However, the reparative impulse of Ottinger’s revisionist narrative falters early. While the wall text in the Primitivism room rightly scolds the European Primitivists for appropriating non-Western artworks “with scant regard to their original function or significance”, the exhibition itself includes little information about the function and significance of the two small African works on display, a Kota reliquary figure from the Republic of Congo and a Dogon statuette from Mali. The raised arms of the Dogon figure, we are told, is a posture “often interpreted” as a gesture of prayer which “may also” represent an appeal for rain. Are we to believe that it is not possible to confirm these speculations? That there are no contemporary Malian scholars who might be able to offer insight here, or at least flesh out this vague interpretive text? Both the Kota and the Dogon works were gifted to the Pompidou by Susi Magnelli, who with her husband the artist Alberto Magnelli was an acquaintance of Picasso and assembled a substantial collection of African art during the 1930s. This provenance clarifies the extent to which the exhibition remains deeply imbricated in the mindset of European Primitivism. The Kota and Dogon works are decontextualised stand-ins for the similarly decontextualised artworks that inspired Picasso, and the tokenistic way they are presented here reproduces, rather than repairs, the original violence of the Primitivist impulse. And really, it couldn’t be otherwise. If the full, rich “function and significance” of even one of the non-Western artworks that Picasso used as inspiration was actually articulated, it would demonstrate just how superficial and foolish his interpretation of these works actually was. In order to maintain Picasso’s greatness, it is necessary to repeat his gesture of theft and erasure.

Another form of misrepresentation is performed in the room dedicated to “Salon” Cubists, including artists such as Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay and members of the Duchamp clan. Here the wall text is quite openly disparaging, cueing viewers to understand these artists as second-rate imitators who misunderstood Cubism. They saw it “as a style, rather than a more fundamental philosophical or scientific endeavour”. Their “decorative” paintings deviated from “Braque and Picasso’s ‘true’ Cubism”. It is striking that when Picasso deviated from an established norm it is framed as innovation, but when other artists did the same it is presented as misunderstanding. It seems to me that the creamy slabs of paint in María Blanchard’s Child with a Hoop (1917) indicate an interest in tactile materiality that is quite different from the brittle fracturing of Braque and Picasso’s works, but nevertheless extends from Cubism’s preoccupation with the representation of three-dimensional space. The lines incised into the heavy, thickly stratified surface of Blanchard’s painting contrast wittily with stamped decorative motifs—reminiscent of scroll-like foliage in a wallpaper design—which float across the work like cloud shadows. Blanchard worked with a tiny fraction of the resources that Picasso was able to command and it’s frustrating to imagine the creative directions her practice might have taken if she had been better supported. However, as with the Kota and Dogon sculptures, giving a fuller and more accurate account would distract from the main agenda: Blanchard’s work is primarily here to evidence the reach of Picasso’s influence and the inimitability of his approach.

A select few artists are allowed to hold their own in The Picasso Century. Georges Braque, notably, is not only represented by his Cubist works of the 1910s but also by two strange and interesting classical figures from 1922 and some absolutely beautiful still lifes from the 1940s. When artists are allowed out from Picasso’s shadow more interesting conversations between the works can unfold: such as that between Braque’s earthy, painterly Canephora (1922) and the creepily inert, remote figure in Picasso’s The Spring (1921), or the compelling use of black in both Braque’s The Living Room (1944) and Picasso’s utterly gorgeous The Enamel Saucepan (1945). In contrast, while the three paintings by Wifredo Lam are given their own room, it is a rather disparate selection that again doesn’t allow much of a sense of the artist’s practice beyond the interests he shared with Picasso: The Meeting and Canaima (both 1945) bristle with ancestral energy and seem to have very little in common with the meltingly sensuous Untitled (1942).

The myth of greatness serves to isolate artworks. Transformed into icons, they are set apart from the interactions and engagement that keeps works of art alive and relevant. The Picasso Century obviously does a disservice to the artists whose practices are framed as the raw material for (or derivative foils to) Picasso’s creativity. However, the show’s inability to free itself from the heroic rhetoric of the blockbuster also does a disservice to Picasso’s own work. The large display of his 1950s ceramics, for example, shows his sometimes clumsy and playful experiments with a different medium. However, these are literally overshadowed by a wall-sized video projection that serves to reiterate his virtuosity in extremely conventional terms. A looped animation recreates a Picasso drawing line by line: rapidly and confidently, a sketch of an aging male artist painting a voluptuous female nude in his studio appears on the screen. Drowning out the narrative of practical experimentation told by the ceramics, the animation includes no false starts, no mistakes. Not only does it prioritise, once again, a conservative vision of a male artist using a compliant female body to display his prowess, but it pretends that Picasso never faltered or was wrong. It makes him inhuman.

Ottinger is exactly right that Picasso needs to be understood in context: this is precisely how we can walk back the tedious machismo of the “genius bad boy” image. But this goal is at odds with the machinery of a blockbuster that sells glimpses of masterpieces for a \$30 entry fee, is deeply reliant on a conservative and inaccurate conception of the nature of creativity and also underpins the financial operations of the museum. If you’re going to the NGV, I’d recommend the Queer show.

Anna Parlane is a lecturer in art history and theory at Monash University.