Installation view, Alexandra Peters, The Graven Image, 2025, The Warrnambool Art Gallery. Top: Alexandra Peters, Sunset Clause, 2025, acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screen-print medium and paste on vinyl, 200 x 360 cm (3 panels, each 200 x 120 cm). Middle: Alexandra Peters, Foreign Line Extracation V (Overture), 2025, acrylic, vinyl, polyurethane ‘open cell’ foam, ductile iron, pine, steel, enamel, 27 x 460 x 38 cm. Below: Alexandra Peters, Polity (Latent State), 2025, acrylic with screen-print medium and paste on leatherette, pine, steel, enamel, 100 x 650 x 120 cm. Courtesy of The Warrnambool Art Gallery

The Graven Image

Sueann Chen

This is my first time in Warrnambool. I am driving down the Princes Highway at 100 km/h with my painter friend Evie, Egyptian pop ballads spilling through the car speakers. Evie, whose artist father lives a few towns away, tells me that Warrnambool is often called the Shipwreck Coast—a name earned from one of the most treacherous and tragic stretches of coastline in Australia. She mentions the volcanic crater nearby, Tower Hill, its chocolate soils forming the bedrock of Warrnambool’s identity as a dairy and cattle capital. Fertile ground born of an eruption thirty-thousand years ago. For the Gunditjmara people, these volcanic plains sustained one of the world’s oldest aquaculture systems; for settlers, they became the foundation of pastoral expansion and dairy wealth during colonisation.

Installation view, Alexandra Peters, The Graven Image, 2025, The Warrnambool Art Gallery. Courtesy of The Warrnambool Art Gallery

I am here for Alexandra Peters’s first institutional solo exhibition, The Graven Image, at The Warrnambool Art Gallery. The exhibition brings together a constellation of large-scale works between printmaking, painting, sculpture, and installation: gas pipes and canisters repurposed as supports, banquet tables draped in heavy pleated leatherette, pre-existing vinyl flooring co-opted as a work by Peters, and gestural canvases whose surfaces strain against the antiseptic green walls that contain them. Encountered here, in Peters’s hometown, the exhibition feels inseparable from its setting, inviting a reading shaped as much by place as by practice.

The title, The Graven Image, evokes the long-standing suspicion of idolatry in the Abrahamic religions, where images are regarded warily due to their ability to collapse transcendence into material form. Peters’s work, however, is less concerned with representation than with structure. Through her use of pipes, scaffolding, and industrial flooring, she destabilises the supports on which painting—and the wider systems of culture and industry—are built. While the phrase “graven image” refers to idolatry, Peters’s exhibition contends with another possibility: images not as idols but as thresholds—sites where instability, rupture, and the underbelly become palpable.

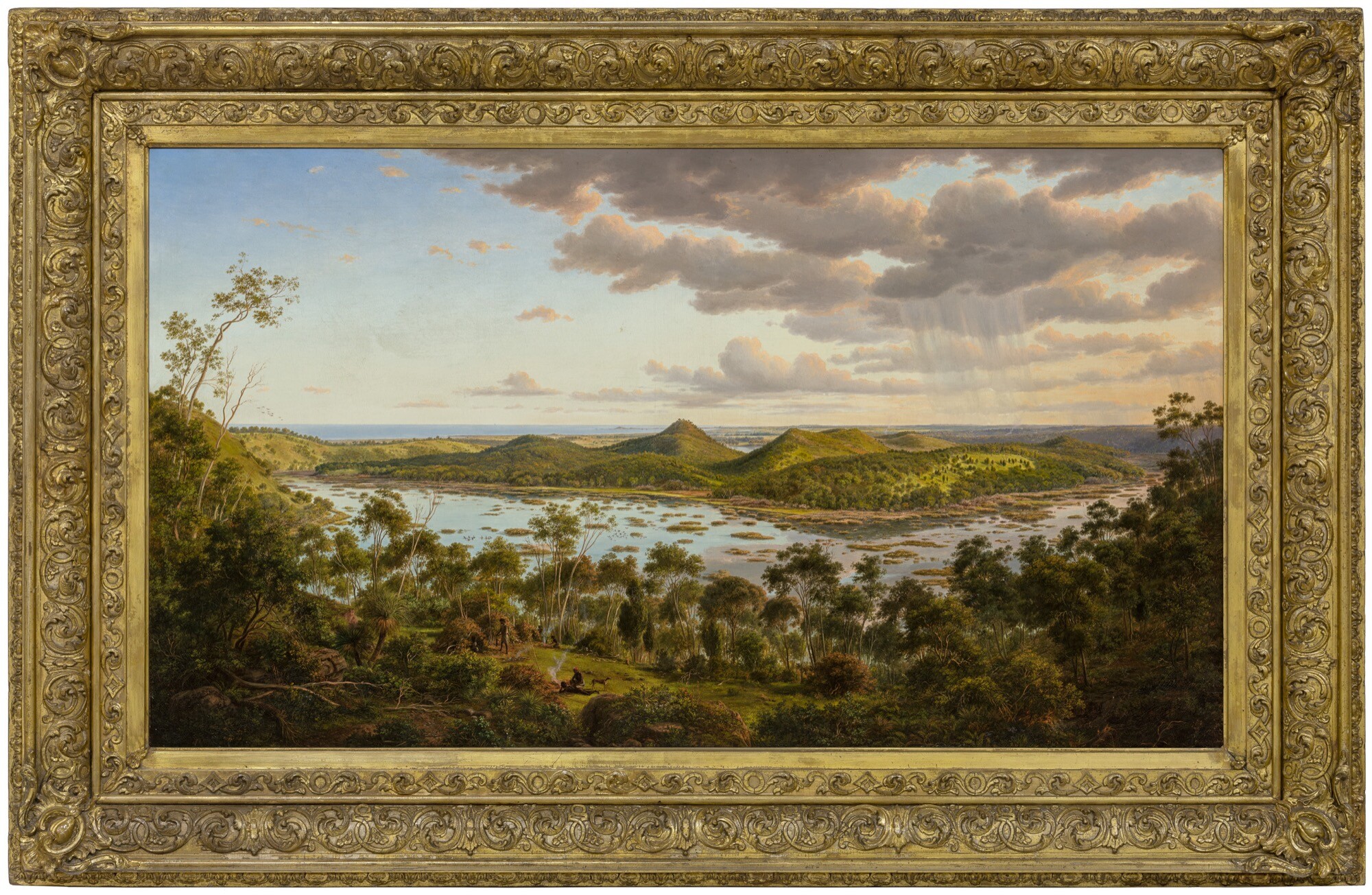

Eugene von Guérard, Tower Hill, 1855, oil on canvas, 69.0 x 122.0 cm, The Warrnambool Art Gallery, Victoria. On long term loan from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. Presented by Miss Effie Thornton, 1966. Courtesy of The Warrnambool Art Gallery

Walking into The Warrnambool Art Gallery, it is hard to miss Eugene von Guérard’s Tower Hill (1855)—the only work in the permanent collection cordoned off with a polite stanchion, marking its special status. The oil painting, depicting the nearby volcanic crater, has long anchored both the gallery’s collection and the town’s cultural memory. In the 1960s and 70s, the canvas took on a second life: conservationists and Gunditjmara custodians drew upon it as a visual archive, using its meticulous and forensic detail to guide the replanting of native vegetation. Read less as a romantic vista than as a botanical record, von Guérard’s painting became instrumental in reshaping the very landscape it depicted. In this shift, Tower Hill reveals painting’s paradoxical capacity to exceed representation, operating instead as infrastructural frame through which the landscape itself could be reconstituted.

What is striking about von Guérard’s Tower Hill is the way it reconciles a site of rupture into pictorial stability. A volcanic crater—the product of violent eruption, a hole in the earth—is rendered as a coherent and harmonious landscape. The painting works to stabilise, to naturalise an absence, presenting wholeness where there is a cavity. This relationship between plenitude and void resonates uncannily with Peters’ practice. Peters’s works, by contrast, insist on precarity. Her large-scale works stage painting as a structure perpetually at risk of collapse: supports exposed, surfaces fractured, marks oscillating between control and dispersal. Where von Guérard’s canvas sealed the wound of eruption into a romantic whole, Peters insists on keeping the fissure open, drawing attention to the instabilities upon which structures rest. Tower Hill thus transforms once more, serving as a local hinge through which The Graven Image finds its point of entry.

The Graven Image unfolds as an almost military environment, marked by its wash of surgical green and unnerving leatherette pleats. Foreign Line Extraction V (Overture) (2025) is a length of green steel gas pipe, sealed with “open cell” foam, that stretches almost the full width of the gallery. Its span is amplified by the gallery’s existing vinyl coin-tile flooring, which Peters reclaims as Leg over Leg III (2025), as a supporting structure of the show. As a floor-work, Leg over Leg III underscores the site-specificity of the exhibition, its rootedness in Warrnambool. The pipe rests upon Polity (Latent State) (2025), an oversized rectangular table, cushioned and skirted in pleated leatherette, draped with a funereal-heaviness. The Polity (Latent State) appears to erupt from the gallery’s left wall like an architectural prosthesis, an extended arm supporting the pipe.

The room’s green tint lends the installation an antisepsis, a sense of controlled cleanliness and corpse-like rest. At the same time, the pleated skirting recalls the drapery of banquet tables, evoking histories of ritual feasting and abundance. This dialectic—aesthetic austerity and ceremonial indulgence, sterility and opulence—animates Foreign Line Extraction V (Overture). Unlike Peters’s former installation, staged at ACCA for the 2024 Macfarlane Commissions, where the pipes flirted with theatrical plausibility by appearing to belong to the gallery’s architecture, here the pipe is conspicuously unconnected from the wall. Severed from any system, it no longer pretends to function as a conduit of material flow but as a symbolic channel, closer to an altarpiece than to infrastructure. An inert fragment that, in Warrnambool, echoes less as abstract form than as a ghost of the infrastructures that have long sustained the region’s industries. In this guise, the pipe bears its contradictions openly.

Alexandra Peters, Common Seal, 2025, acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screen-print medium and paste on leatherette, pine, steel, enamel, 150 x 75 cm. Courtesy of The Warrnambool Art Gallery

Against this atmosphere of restraint, two paintings, Sunset Clause (2025) and Midnight Hammer (2025), break open in saturated colour: acrylic and screenprint compositions dense with layered gestures, their intensity pushing back against the room’s pallor. The pipes of Foreign Line Extraction V (Overture) generate an atmosphere of restraint that frames the eruptive, gestural painting above. Sunset Clause is an abstract-expressionist triptych awash in crimson and black. The painting is explosive: vigorous gestural sweeps of black paint cut across a screen-printed white layered form. The violence of the brushwork feels almost catastrophic, as if the surface records a collision between painterly expression and industrial marking. The title Sunset Clause carries juridical weight, invoking agreements that expire after a fixed period. Within the work, this sense of expiry resonates with the imagery of rupture and erosion: the painting appears as though something has already passed through it, leaving traces of violence and sediment.

Warrnambool’s pastoral economy finds its clearest inflection in Common Seal (2025), perhaps the work most easily read through the lens of Warrnambool’s local industries. The work takes the familiar form of a butcher’s or deli meat-ticket—those disposable slips that regulate the order of service—and enlarges it into a wall-mounted emblem. Fabricated in imitation leather and steel, its pale mint surface blends with the green walls, while alphanumeric codes and motifs puncture its neutrality. What is usually a flimsy fragment of consumer infrastructure is here monumentalised, transformed into a permanent and strangely ceremonial object.

The work recalls the infrastructures of meat processing and sale, reframing them as part of the town’s lived environment and history. By aestheticising the ticket into an emblem, Peters estranges it from utility: it becomes at once infrastructural and ornamental, bureaucratic and ritualised. Of all the works, Common Seal was the most difficult to parse, perhaps because it so overtly insists on its local charge. Like Leg over Leg III, Common Seal anchors the exhibition in Warrnambool, drawing out the ways in which The Graven Image is inseparable from the place in which it is staged.

Alexandra Peters, Midnight Hammer, 2025, acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screen-print medium and paste on vinyl, 180 x 260 cm (2-panels, each 180 x 130 cm). Courtesy of The Warrnambool Art Gallery

Opposite Sunset Clause is Midnight Hammer (2025), a searing diptych frame of midnight blue and incandescent red, its intensity partially obscured by sweeping drips and stains of black. The placement of the two paintings creates a charged axis across the space, as if they confront one another through their volatile fields of crimson, black, and layered marks. On 22 June 2025, the United States Air Force and Navy struck three nuclear facilities in Iran under the code name “Operation Midnight Hammer”, during the 12-day Iran–Israel war. This echo of geopolitical force and violence reverberates through the painting’s volatile composition, staging the collision of rupture, combustion, and containment.

Midnight Hammer feels at once volatile and contained: a luminescent core erupts beneath the weight of dark, almost corrosive gestures that drag downward like sediment or oil slick. The painting operates through a frame-within-a-frame construction: a central field of incandescent red and black gestures is enclosed by a darker navy border patterned with repeated motifs. This inner/outer framing produces a double register—the eruptive centre suggests volatility, combustion, or collapse, while the surrounding frame imposes order, codification, and restraint. Yet rather than stabilising the image, the border intensifies its instability, as though chaos has been quarantined and contained. Unlike the crater at Tower Hill—sealed into harmony by von Guérard—Midnight Hammer allows on its contradictions and holds rupture in an uneasy suspension.

Detail of Alexandra Peters, Polity (Mid-State), 2025, acrylic, pigment and water-based ink with screen-print medium and paste on leatherette, ductile iron, pine, steel, enamel, gas canisters, 80 x 180 x 180 cm. Courtesy of The Warrnambool Art Gallery

The stability of the image further contested by its relationship to Polity (Mid-state) (2025), a sculptural installation that rests between Sunset Clause and Midnight Hammer. It is a capped pipe cemented in place atop a round table draped in pleated leatherette, its legs upholstered with black gas canisters. Either side of this sculpture, the two paintings erupt, while the sculpture monumentalises blockage, stasis and inhibition. Together they form a triangulated drama of release and pressured containment, where volatility and rupture are made visible precisely through their suspension.

Upon closer inspection, Polity (Mid-state) is faintly screen-printed with the United Nations seal. In the face of the war on Gaza, and the struggle for Palestinian self-determination, the emblem reads less as a guarantor of justice than as a hollowed-out symbol, its authority stripped back to mere decoration. What should signify circulation and diplomacy becomes instead a marker of blockage and inhibition. Yet beyond this global register, the materials themselves embody the haunted residues of local economies: imitation skin manipulated into heavy pleats, gas canisters standing in as legs, and a severed pipe in place of a neck. A sinister ritualistic quality clings to the sculpture, as though the familiar infrastructures of industry had been reassembled into a body gone awry.

In contesting the role of the image, Alexandra Peters reimagines it as structure and intervention. Here, painting refuses to seal over absence or to stabilise rupture as Tower Hill once did. Whereas von Guérard’s landscape naturalised rupture into pictorial stability and even mobilised it as infrastructural vision, Peters’s exhibition insists on keeping the fissures open. Her works operate as a patterned field, a disruption of order. What emerges is the image as threshold: a precarious site where instability is held open, and where the invisible and ineffable can be depicted without being contained. Set against Warrnambool’s volcanic landscapes, shipwreck histories, and economies of extraction, The Graven Image reads with greater clarity. It reframes Peters’s practice with incisive force, revealing not only the haunted residues of local and global industry, but also the unstable grounds upon which painting itself must stand.

Sueann Chen is a writer, currently living and learning in Naarm, Melbourne. She is a PhD candidate in Art History and Theory at the University of Melbourne.