Susan Jacobs, The ants are in the idiom

Ursula Cornelia de Leeuw

The referential density of Susan Jacobs’ immense exhibition at Buxton Contemporary, The ants are in the idiom, is almost overwhelming. Like an Ezra Pound epic poem or its precursor Dante’s Divine Comedy, such excessive citations necessitate a depth of knowledge, here expressed through Jacobs’ cryptic interplay between the visual and the linguistic, the aesthetics of matter and its reference to research. The history of ox-hide ingot currency, the lamb of Tartany, the sottobosco and vanitas paintings of the seventeeth century, as well as the chemical experiments of Jan Baptista von Helmont and Louis Pasteur, make up the bibliography of Jacobs’ latest offering. However, unlike many masters that came before her, Jacobs is not interested in concluding a grand narrative or synthesising an understanding of its dialectical principles. Rather, she presents the viewer with a series of riddles, the first of which is embedded in the exhibition title itself. The exhibition’s curator, Jacqueline Doughty, provides its key in her catalogue essay, wherein the etymology of the word “answer” in part derives from the word “ant”, meaning “front, forehead”/ “in front of”/ “before”. The ants are in the idiom is thus less a riddle and more a pun, holding the word “answer” as its core while continuing to draw question marks around the exhibition’s cryptic visual syntax.

The exhibition opens with Hindsight 20/20 (2020), a wall mount of 101 identically shaped gypsum tablets. They are cast in silver, bronze and gold leaf in the shape of a rear-view mirror found by Jacobs on the streets of London. The story goes that Jacobs momentarily glimpsed the Virgin Mary in its reflection, but it was simply an optical illusion. Hindsight is followed by A Recipe for Scorpions (2021), a staged alchemical experiment by the 17th century Flemish chemist Jan Baptista von Helmont.

As per the given recipe, here recorded on a chic colour-block panel, a basil leaf placed between two bricks is intermittently misted by an elaborate machine. The hypothesis is that a scorpion will emerge from the vegetal matter. Another Helmont experiment, A Recipe for Mice (2022), is practised in the next room and follows a similarly far-fetched theory of spontaneous generation. Here, Jacob’s long-lasting interest in scientific experimentation can be observed, as in her 2011 exercise of diamagnetic levitation while in residence at Gertrude Contemporary.

The rest of the show features the sprawling Market Fray (2020-22), consisting of many smaller works arranged in the manner of a vendor’s bazaar. Some of these arrangements expand upon motifs, materials and methods from Jacobs’ 2018 show, Animal Grammar, exhibited at the London gallery Mackintosh Lane, run by Australian artists David Noonan and Anna Higgins and British artist Kira Freije. Repetitions include the flayed plastic bag cast of Market Mesh (Bag Hide) and the sculptural text of the Cope (Tree) (2022), both made of bronze. The installation of Market Fray also includes an element of site intervention, as Jacobs has built two non-load bearing columns to further lend a market environment to the gallery, while also raising conceptual questions around the language of architecture and its function.

As detailed by Jan Bryant in her analysis of the exhibition, these forms were inspired as Jacobs observed a recycling plant in East London, repeating a detrital sense of found material instigated in Hindsight. The act of site interventionism runs through Jacobs’ practice, as in 2011 when she removed a plaster wall separating her Gertrude Contemporary studio from the exhibition space, simultaneously revealing the gallery’s archival cabinets. As reported by Amelia Winata in her recent profile of the artist, Jacobs’ interventionism resonates with her former disciplinary experience in the drawing department at VCA where, in preparation for her 2007 show at Ocular Lab, Raafat Ishak urged Jacobs to “take the drawings off the page and insert them into space”. Thus, For Every Solution There is a Problem (2007) included the installation of a large dead tree, a false wall and a timber door dispersed throughout the gallery. In The ants are in the idiom, the limits of drawing are extended to the architectural lines and composition of the site once more through an interventionist means. To expound further upon the particularities of this expanded field would take a more dense and diagrammatic critic.

At the exhibition’s conceptual centre, says Jacobs, is the experience of pareidolia:“that process when we clock things and we want to make meaning out of them so we can understand our environment”. This process refers to flaneur-like way by which Jacobs gathers materials, and perhaps also the type of encounter that occurs while scavenging in archives. Stylistically, The ants are in the idiom shares a resemblance with the smooth bronze and blanched casting of Post-Minimalism, combined with the entropic, agrarian trappings of Arte Povera. In scale, however, it is more akin to the minutiae of the contemplative assemblage artist, erring on the side of Yves Klein-kitsch. The French archival artist and sculptor Camille Henrot comes to mind. However, if we were to continue with this art- historical game, above all Jacobs’ stylistic counterparts lie with the 1990s “research-based” arts, echoed in the likes of fellow antipodeans Michael Stevenson and Nicholas Mangan.

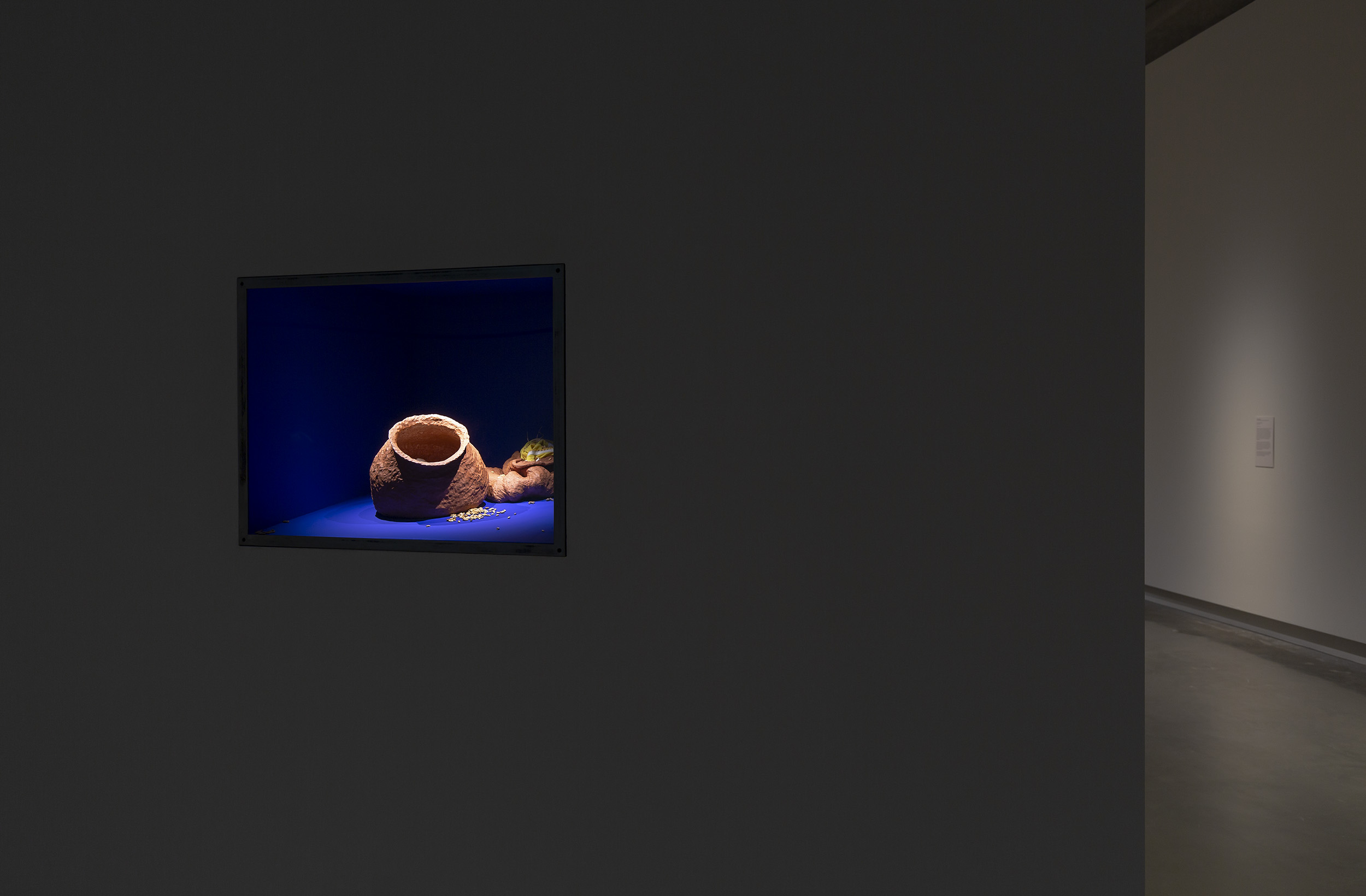

As Stevenson described in an illuminating conversation with artist Simon Denny, the term “research-based art” evolves from the notion of archival art but with less of an emphasis on documents and more of an aesthetic focus on the “blurring of research and practice as enacted in the studio”. Here, a “necessary conflict between materials and research” is perpetually enacted. In other words, it is more about giving form to the tension between the research of a practice-based methodology and the matter that conducts its exhibition. This is certainly the case for The ants are in the idiom. In the final gallery, Jacobs poses yet another alchemical test in Pasteur’s Grapes Inverted as the Lovers (2022). Here, Jacobs transforms an archival reference to microbiologist Louis Pasteur’s technique of fermentation into an aesthetic reference to Magritte’s kiss. It is in this final experiment that the tension between research and its register as an “artwork”, an object of aesthetic pleasure and contemplation, comes to the fore most dramatically.

In this vein, Jacobs’ work is also the product of the increasing revival of science and art, an interdisciplinarity that was promoted extensively in the ‘90s by MIT and the journal Leonardo. For me, such an emphasis takes on a sinister air when one considers the increased likelihood of art being funded when linked to the utile research base of science…but I digress. Tom Holert’s 2020 book Knowledge Beside Itself, published by Sternberg Press, describes this epidemic in greater detail. But Jacobs’ intersection with science and experimentation seems to be less interested in the cutting-edge and more invested in the nonknowledge of its mystification. Her interest in Helmont, a chemist who referred to his doctorate in medicine as “reaping straw and senseless prattle”, evidences this tendency. As Jacobs has stated, “For me, it’s about wonder and not knowing, and the undoing of trying to solve something … What actually comes from the fallout in the art process is more interesting … The thought process isn’t literal”. Not knowing appears to be the domain of art’s inherent excessiveness. Throw science into the mix and the artist takes on the air of a quack doctor or mad scientist. This tendency has revealed itself on more distasteful occasions; I’m thinking of Stelarc and his disturbing revival in David Cronenberg’s new film Crimes of the Future (2022). But Jacobs does something more interesting in her integration of studio methods and research into the matter of the exhibition. Here, scientific research is only part of a wider aesthetic interrogation into the antiquated and its tension with the synthetic modern.

The use of outdated techniques has been of interest to Jacobs for some time. In her 2013 work for Melbourne Now, Wood flour for pig iron (Vessel for mixing metaphors), she fabricated a version of Hermacite, a late nineteenth-century material made from animal blood and wood flour. A general outmoded air of an agrarian or feudalist variety surrounds The ants are in the idiom, especially the Market Fray. But this fashion is consistently interrupted with something actively referencing a later time of mass production. Take the component Market Mesh, consisting of The Noble Rot, Bag Hide, Rotten Rare and Fox Hole. The materials: gypsum, acrylic, shellac, plastic, perspex, silk moire, epoxy, graphite, found wood. The appearance: a butcher’s rack of items for sale. The most notable of these objects is the aforementioned Bag Hide, a cast of a flayed plastic bag that has the appearance of an animal hide. As presumed “old” and “new” forms of production meet in this object, it encapsulates the stylistic tension that plays out across the exhibition, where the synthetic and the antiquated meet in a practice inherently linked to artistic methods of “the contemporary”.

From these multitudinous aesthetic, methodological and technical convergences inevitably arise the question of what The ants are in the idiom is “about”. It is about language and its impossibilities, of understanding one’s surrounds through their de-contextualisation, environmentally and temporally. It is about brute material as it meets reference, biography and aesthetic proclivity. However, the exhibition is also about the supposed meaninglessness of this practice, of the artist’s production of knowledge through conceptual matter that requires a keen eye to decipher, without the promise of an answer. Only riddles. In this sense, The ants are in the idiom is also about the love of research and experimentation for their own sake. Here, meaning is not discursive, but is revealed as sources take flight into form.

Ursula Cornelia de Leeuw is a writer between Adelaide and Melbourne.