Terre Thaemlitz, Love Bomb/Ai No Bakudan

Robert Schubert

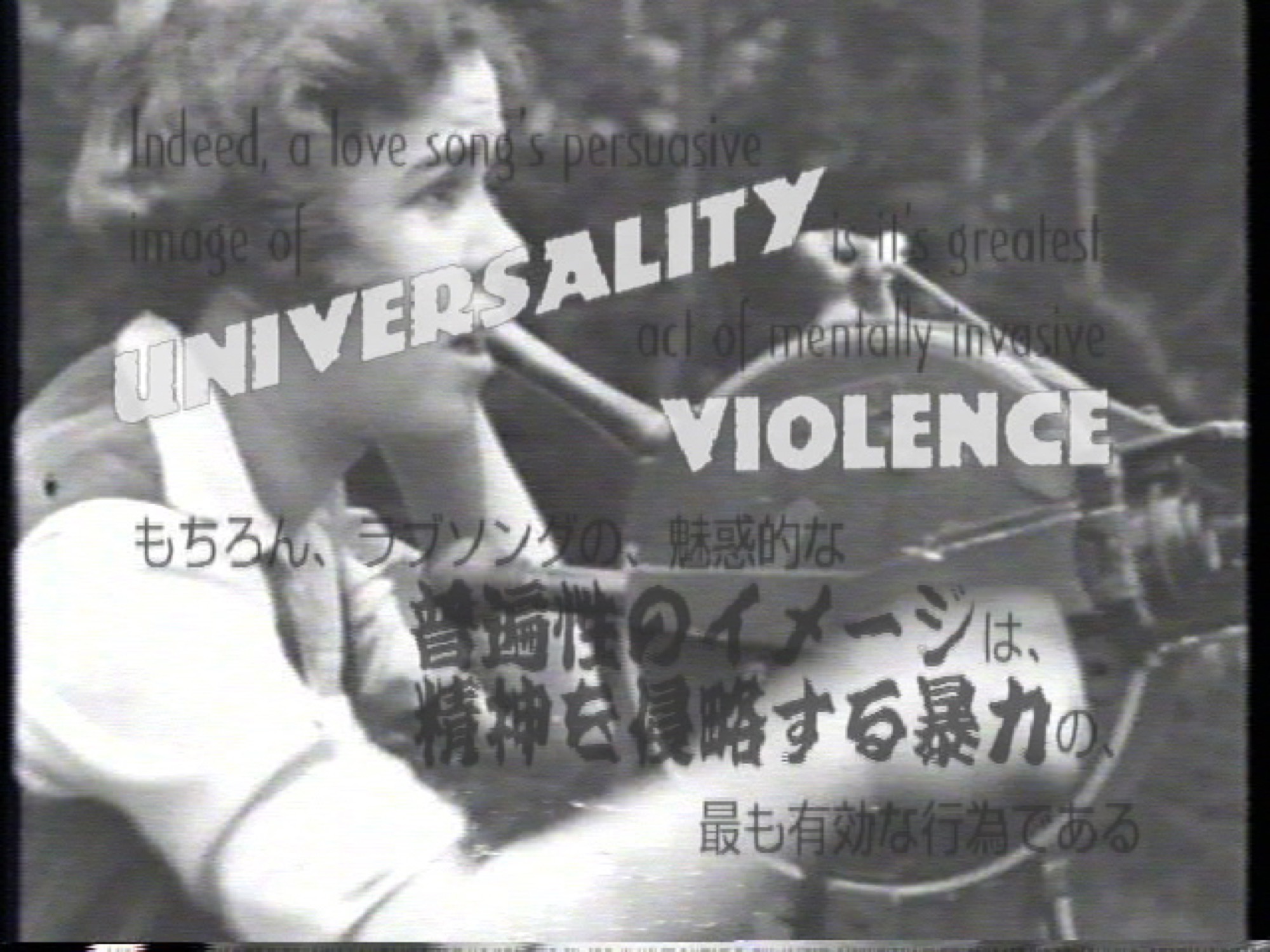

Love is … a redundant construction of pacifying hysteria, a mandatory insult to appease our senses. Its persuasive image of universality is its greatest act of culturally invasive violence. A perverse mirror of the cut.

DJ Sprinkles is something of an anomaly in house music. She is an American born trans music producer living in Japan for the last 20-odd years, has produced one of the most celebrated deep house records (Midtown 120 Blues, 2008) and continues to release house music while staying exceptionally close to what she knows best. Deep house music, which for her is specifically located between New Jersey, the East Village and 10th Street, New York between the years 1986-1992.

As Terre Thaemlitz (although the two appear to be interchangeable as are pronouns him and her, and he and she), she writes about music, technology and non-identity politics collected in Nuisance – Writing on Identity Jamming & Digital Audio Production (Nuisance). She is well versed in and critical of the theoretical possibilities of post-structuralism and identifies more as a cultural worker than a visual artist, even when producing Soulessness for Documenta 14 in 2017. Her distain for art schools should also not go unnoticed.

Thaemlitz was in-house for a screening of her sound/video work Love Bomb (2004) with other videos, collages and graphics at Substation, located in Melbourne’s distant Western suburbs, as part of the Asia-Pacific Triennial of Performing Arts. Love Bomb hasn’t had an airing in Australia since it first screened in Brisbane in 2004, and the work has its beginnings in Thaemlitz’s music production. It is taken from an album she released in 2003 on the Mille Plateau label with the collage of found images completing the work a year later. As with most things Sprinkles/Thaemlitz, the sound track is made of processed electro-acoustic samples and voice and the images looted from the internet or an archive of images Thaemlitz finds, in one instance we know of in the work, literally on the street.

The work is structured around 14 chapters but there is scope here only to discuss a few, although you can find the text sans images here. The first sequence of pictures are screenshots of the website Chicks with Dicks and is deliberately in your face. This should not be unexpected given Thaemlitz’s sometimes playful and irreverent questioning of gender binaries, although here it is less that than an unambiguous statement about embodied trans-gendered corporeality. This chapter also set the aesthetic challenge for what follows. Part of the work’s audacity is that it moves along an anti-aesthetic trajectory that involves deliberately obscured images, cut at times at a frantic pace, all the while keeping pace with the copious texts, which primarily work to partially obstruct the visual imperative to look. Using text in this way is a structural refrain Thaemlitz relies throughout the work (and other video works on show), and like word-based works by similar artists, text and the syntax of image-making is used as a distancing technique to assert the discursiveness of looking.

The text states the purpose of work upfront—love is an infinitely manipulated cultural and political construct, more selfish and violent than we suppose within our own inter-relational context. The love in Love Bomb is broad, historical and political. As Thaemlitz explains from “Helen of Troy (love of sex) to the Christian Crusades (love of religion) to Nazism (love of the fatherland) to Operation Infinite Justice (love of freedom) …” (Nuisance). This is how Thaemlitz engages with a critique of the culturally manufactured universality of love, at times reflecting a criticality of love that declares terrorism is an act of love (of god and community) and that domestic violence is evidence that love of the other is an act of violence. Love Bomb gets points for this if for no other reason.

In Chapter 2, ‘Between Empathy and Sympathy is Time (Aparthied)’, Thaemlitz deploys speeches radioed across South Africa as the voice of the ANC. Again, there is text and most if it didactic and located in history and place, the speeches delivered with the pithy necessity of a language engaged in political struggle. “The lone policeman must be made a target”. “We must learn to make homemade bombs”. However, the masculine tone and timbre of the voice is slightly off, but not in a bad way. There is an undertone, or a quiet melody, an other voice that is only later and briefly confirmed to be Minnie Ripperton singing Loving You, and the overall effect is a kind of audial, gendered undoing.

This technique is used a few times in the work and is in a way a technology that elicits its fair share of philosophical possibilities. As Thaemlitz later confirmed on the night, she used a standalone computer processing program called Codepend developed by Christopher Penrose. This process is different to vocoding for example, with which the program shares a vocal heritage and was popularised by Cher in Believe, in one important way. As she explains in Nuisance, the technology allows each file to contribute to the output audio file in a non-master and slave relationship typical of music programming. In this sense, the relationship is non-dialectical, creating what is possibly a whole new vocal type made through technical rapprochement rather than a synthesised overlay of what might be considered digital pop trickery involved in a power struggle. It could be a forced, even ironic, exercise of opposites distracting; but instead it suggests that Love Bomb, while imbued with much aesthetic grumpiness, also has moments of subtle visual and acoustic surprise.

This same technique is deployed more strongly in Chapter 6, ‘Sintesi Musicale Del Linciaggio Futurista (Musical Synthesis of Futurist Lynching)’. Again, Thaemlitz interweaves two disparate moments in history, albeit at a slower pace. This includes texts from the Manifesto of Futurism from 1909 with Thaemlitz’s textual telling of a lynching in her home town in Springfield Missouri that took place on Good Friday in 1906. In some ways this part of Love Bomb is where Thaemlitz’s aesthetic logic comes into its own. Peppered with random archival footage of the city privileged by the Futurists and collaged images Thaemlitz made that include albeit briefly a lynching, the sequence shifts seamlessly between a factual description of what happened in Springfield, the lyrics of Lewis Allan’s Strange Fruit and, later, the bravura of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto, a conjunction that is included here because it works just as well on the page:

It was on Good Friday of 1906, the Christian holiday in observation of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, when a God-fearing White mob converged in the town square of my hometown Springfield, Missouri. In their possession were three Black men whom they had dragged from suspicious holding in the local jail to the foot of the Gottfried Tower. The tower was disassembled in 1908, but accounts describe it as a metal-frame structure topped with a replica of the Statue of Liberty that was illuminated by electric light.

We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

Courage, audacity, and revolt will be essential elements of our poetry.

… .

We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, … the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

… .

Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.

… .

We will glorify war - the world’s only hygiene - militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.

We will… fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot.

… .

The choice of these two narratives although clearly unrelated historically and culturally, creates a movement between the sameness of, say, the metal-framed tower and the Futurist lusting after machinery or, even more directly, the image of Futurists singing of great crowds excited by riot against a similarly nationalistic mob no less excited in lynching black men from a tower whose symbolism the Futurists would no doubt have lauded. People surely do awful things in the name of love.

Love Bomb is a difficult work because it projects a kind of relentless exteriority through found images and sounds, and for this reason shares some of the Warholian virtues of Pop Art. It is also consistent with Thaemlitz’s comment on the night that she was nothing but her own representation. And this is what resonates most with the work. In a cultural climate where subjecthood has been reasserted as an art world commodity (yes, Tracey Emin is posting her tedious COVID-19 life online) by an increasingly powerful elite of neo-liberal political interests, there is somewhat differently and significantly nothing about the subject to speak of here. This is hinted at, for example, in Chapter 4 where Thaemlitz includes a recording of her father talking to her three-year-old sister in 1976 whose purpose is less biographical than an exemplar of the subject’s (Sara’s) nascent and fractured struggle into language and culture. This is also true I would argue, of Chapter 5 from which Love Bomb takes its name where Thaemlitz animates a sequence of drawings in what appears to be a confessional tale that aligns ritualised bullying and humiliation with bombs, and sex of many sorts with rain dropping over Manhattan.

The work’s incessant textual intervention coupled with few moments of audial and visual reprieve (heightened at the end by a petit mal-inducing rapid cut of pictures Thaemlitz found in the sidewalk garbage of a gay life lived in New York City ended by AIDS) is testament to the continuing validity of appropriation art as a meaningful anti-aesthetic and historically rich project. On the night, Thaemlitz insisted her aesthetic project be understood as a failure. Taking her at her word, Love Bomb is a failure—of representation as much as of self, identity and politics—and for this reason remains a powerful counter point to much of what passes for art now.

Robert Schubert has worked in Australian visual culture since the 90s publishing extensively in numerous publications, curating the odd show and founding the first electronic visual arts magazine Globe-e Art Journal in 1995.