Sydney Buries its Past

Tom Melick

I head towards Tin Sheds Gallery on my lunch break, before Sydney Buries its Past officially opens. To get there I pass the University’s Gothic Revival architecture, built during the second half of the nineteenth century from always-damp sandstone, as well as the newish glass buildings, where management work and where I sometimes go to use the toilets. If the founding architecture of the University aspired to Oxbridge, the new buildings glimmer like any other corporate headquarters (instead of gargoyles there’s CCTV). I was told once that the University sold a Picasso from its collection to pay for one of its newer buildings. I’m not sure if that’s true, but it prompts an image of a building suddenly turning back into a cubist painting. What else would we see in the city if buildings revealed their financial sources?

When I was at art school in Sydney, in the early 2000s, the Tin Sheds was often mentioned in passing. We were told it was an important moment, the place to be, for activism and art from the late 60s until the 80s, during the height of the civil rights movement and interrelated social justice struggles. Anti-war and anti-nuclear protests, environmentalism, feminism, Indigenous land rights, anarcho-punk and Marxist vernaculars spilt over Tin Sheds’s corrugated iron walls and into the streets. Their actions took the form of—mainly, though as this exhibition shows, not only—brilliantly inventive posters. But there wasn’t a lot of discussion, as far as I can remember, about how various artists and collectives that worked and hung out at and even lived in the Sheds (there was 24-hour access in the early years) addressed the city specifically; on how they organised themselves, chaotically and, at least initially, non-hierarchically, with whatever they could find or steal, fuelled by counterculture philosophies and calls for the democratisation of art; or what the lessons of the Sheds might be for artists who find themselves both inside and outside institutions, in varying degrees of uncertainty and agitation, and who may be (always are?) looking for alternatives.

Sydney Buries its Past wants to have that conversation. Maya Stocks, the curator, has dug up a selection of materials from the Sheds archives (films, photos, slides and 126 posters, pinned to the wall from floor to ceiling), and placed them back into the Tin Sheds Gallery. This is somewhat meaningful in its own right since it’s the University, not the Gallery, that holds the archives. (I should say here, for some clarity, that Tin Sheds Gallery took the name but not the location. In 1989 the Sheds were absorbed into the School of Architecture, Design and Planning. In 2004 it moved into its current premises and in 2006 the original Sheds were demolished to make way for student housing and University office space.) Stocks has placed her selection of archival materials alongside works by artists, including herself, who are students or alumni or current teaching staff of the Sydney College of the Arts. But unlike other archival activation projects that are often held together with historical empathy or motivated by an overbearing sense of homage (such as John Kaldor’s Public Art Projects), she lets the archival material breathe (and in turn the exhibition). Refreshingly, Stocks does not insist on perfect alignments between past and present. This light touch allows connections to be found in the looking which, in Stocks’s hands, is experienced as spontaneous rather than didactic.

Or maybe Sydney Buries its Past offers a way to glimpse the past as a still unfinished project of the present? We pull a line and see what’s on the other end. I say this because I’ve just come across what Donald Brook—who along with Marr Grounds and Peter Johnson was crucial to setting up Tin Sheds—said in 1976:

The Sheds were and they weren’t part of the university … they were where people went when they had a vision of how art should be conceived and made that was not satisfied by the going institutions … the Sheds collected the malcontents of the “system”.

It’s clear that these Sheds, the ones evoked by Brook, are well and truly gone. But the vision and malcontent? That’s alive and well! Mixed in, you might say, with a present-day pessimism about the (still) going institutions, especially the city’s larger universities and their art schools, with their managerial mania, brand obsession, quantification of research, fee hikes, wage theft, casualisation, and confusing hostility towards what you would think would be their purpose: to be a place where people can study and think and make things.

As if to mount a defence against any attacks by the University, Zoë Marni Robertson’s Mid-Century Barricade (2022) hinders a simple entry into the Gallery. Her paintings of Soviet nuclear control rooms lean crookedly on an assemblage of bookcases, chairs, tables, bottles, engraved glasses, and other found or borrowed furniture—all bound by barbed wire. In the context of the anti-nuclear protest posters also on display, such as Graham Lightbody’s Australian uranium—fuel for disaster (1979), Robertson’s paintings are like solenoids, with history as their current. But it’s all messed up and weird, the paintings seem to say. What was taken out of the ground and promised as an image of the future is now a vintage aesthetic. Meanwhile, its other afterlife lies buried in deteriorating storage facilities around the world as transuranic waste.

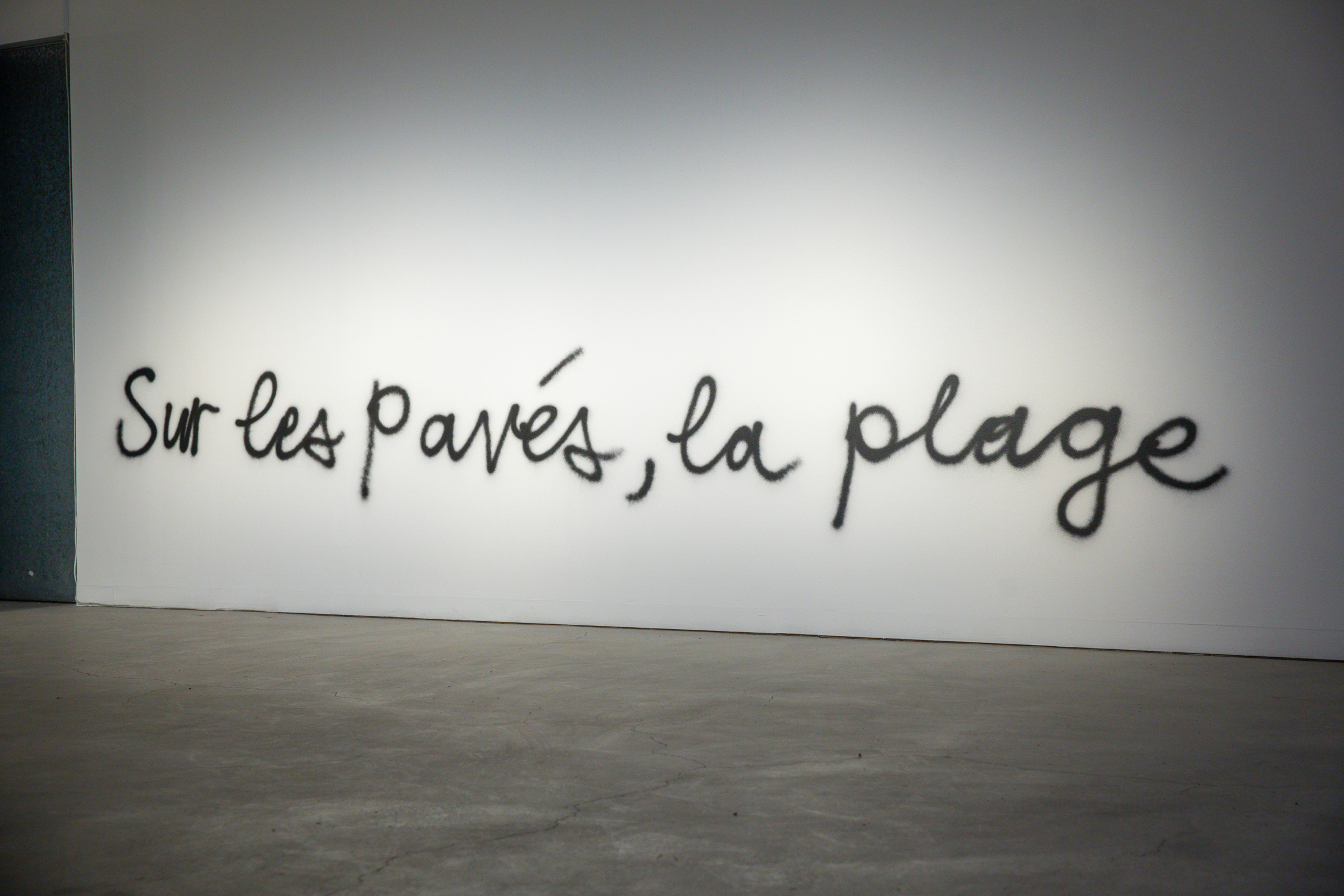

There are other kinds of barricades, too. Mitchel Cumming’s Resumption (Creative Hoarding: Monochrome) (2022), converts the gallery wall into A-Class hoarding (barricades put up by developers to keep people out of construction sites, blocking the view of, usually, a great big hole). The City of Sydney commissions artists to beautify this hoarding “in high traffic areas” while developers go to work behind it. This is a response, says the City on their website, to “community demand for more street art to enliven the streets of Sydney and bring creativity into the everyday”. (Who writes this stuff?) Cumming’s “non-submission” to City Road is not only a monochrome but also part of the Gallery. As the work makes clear, Tin Sheds Gallery is the University’s creative hoarding, a space with a radical past now neutralised and therefore celebrated. What goes on inside doesn’t much matter (this is potentially advantageous). In another work on another wall, also titled Resumption (2022), Cumming has spray-painted a rallying cry of the May ‘68 Paris riots, with one edit. Instead of Sous les pavés, la plage! (“Beneath the pavement, the beach!”) we read Sur les pavés, la plage! (“On the pavement, the beach”.) The slight change (or let’s call it an act of mistranslation) localises the call for revolutionary escape but suggests that radical weather, not Situationist tactics, will be the city’s undoing.

Loss is a common thread in Sydney Buries its Past. Loss of work: as in Mary Callaghan’s 1982 film Greetings from Wollongong, which follows the lives of four unemployed characters during the 1980s recession. And loss in the face of what’s often called “improvement” or “transformation” or “regeneration” of a city. (This history is fleshed out further in a series of film screenings that Stocks has programmed alongside the exhibition.) Capital speaks of “forms changed into new entities”. Since the late nineteenth century, the city has been a developer’s dream, “just money on display” as Iain Sinclair wrote recently about London’s architecture. Toby Zoates’s colourful drawing Neo-liberal Capitalist Impermanence (2022) shows the confluence of urban development and capital in no uncertain terms. The picture hangs on a wall alone, lit like an icon, and records the demolishing of the Regent Theatre in 1998 to make way for apartments. The rest of the city’s icons—the Opera House, Centrepoint Tower, Sydney Town Hall—are also being bulldozed, making the cartoon part-record and part-premonition. In a different approach to ruins, Jack Wotton’s Fragments / 01.01.2020 (2022) returns us to the weather. Twisted and burnt panels of corrugated iron, with dirt and leaves attached, lie on the floor in the centre of the Gallery like three sleeping bodies. At first, I thought the artist had found remnants of the old Sheds, but it seems that this corrugated iron is wreckage from his family home in Wandella, in the Bega Valley. The date in the title suggests they are the remains from the Black Summer bushfires.

Before I leave, I take another look at the wall of posters. What’s striking about the hang is that there’s no single overriding story other than the mad rush that obviously went into their making. An urgent and sometimes reckless making, for all kinds of causes, playing with image and text, or turning text into image. It’s the kind of work inconceivable to university metrics. To protest a uranium mine; to let you know what to do when you get arrested; to tell you how you can stay on the dole; to “Give (Malcom) Fraser the Razor”; to protest the logging of the rainforests; to let you know that Kings Cross Youth Refuge needs volunteers. As Stocks writes in the exhibition pamphlet, the artists used “whatever impressable material was at hand: computer paper, the backs of family health posters, ledgers, newsprint and even yellow x-ray paper pilfered from the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital up the road”. That phrase, “whatever impressable material”, stuck with me—what a good, non-institutional method. Not only for making posters, but as a way into another Sydney.

Tom Melick writes and edits.