Stuart Ringholt: Works on Paper

Anna Parlane

It is a real pleasure to see a show of drawings by an artist primarily known, at least in Melbourne, as the guy who installed a nude disco at the Monash University Museum of Art. Stuart Ringholt’s Works on Paper at Neon Parc comprises a suite of twenty drawings that the artist made in 2014. They are intimate works, but are unlike the discomforting intimacy of Ringholt’s more spectacular participatory and performative projects. They are light and exploratory, like a thought that is being formed as it is spoken.

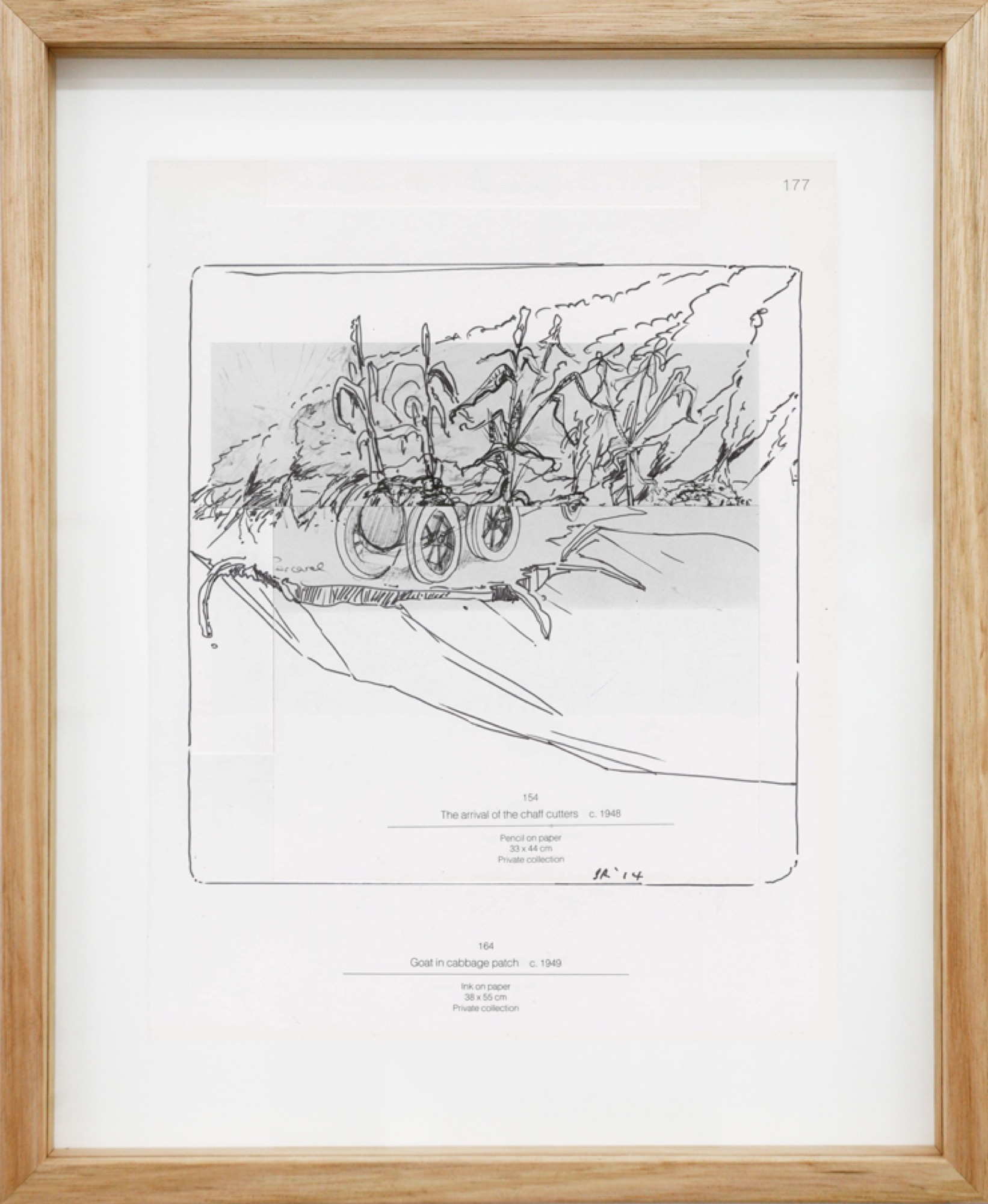

This sense of a process underway is reiterated by the exhibition’s serial format. Each drawing was done in pen on a page excised from the 1989 publication Fifty Years of Perceval Drawings. Ringholt removed the existing John Perceval reproductions, inserted blank sections cut from other pages, and drew directly onto these composite sheets. Acting as a formal counterpoint to the freewheeling drawings, the tidy, serial uniformity of the book pages establishes the exhibition as a tight sequence of variations on a theme.

Ringholt has a long-standing interest in collage and printed material, and this is apparent in his playful redeployment of the publication form. Collaged fragments of the book’s original content provide these works with additional layers (literal and metaphorical), and often surreal juxtapositions between old and new material. The page numbers on the corner of each sheet, for example, act as readymade titles that also double as bibliographic citations. Ringholt has also retained the typed captions of the removed Perceval reproductions, despite their comical incongruity with his new pictures. Oblivious to the disappearance of the works they describe, these captions placidly recount titles, dates and dimensions. My favourite is the (already wonderful) Perceval title Goats Playing the Violin, 1957, which floats inexplicably in the centre of Ringholt’s Page 208. In another drawing, Page 124, a tree helpfully relays the details of the book’s publisher in a speech bubble.

In an earlier series of drawings from 2013, Ringholt reworked pages from a how-to macramé book, extending the neatly twined and woven threads in the book’s illustrations into tangled skeins that romp boisterously across the paper. The series at Neon Parc continues this theme of weaving and stitchcraft, as well as incorporating the needles and clocks that are part of Ringholt’s already established lexicon. As it does in the earlier series, weaving imagery in these drawings serves visually to stitch diverse sources together while also reiterating the work’s composite logic.

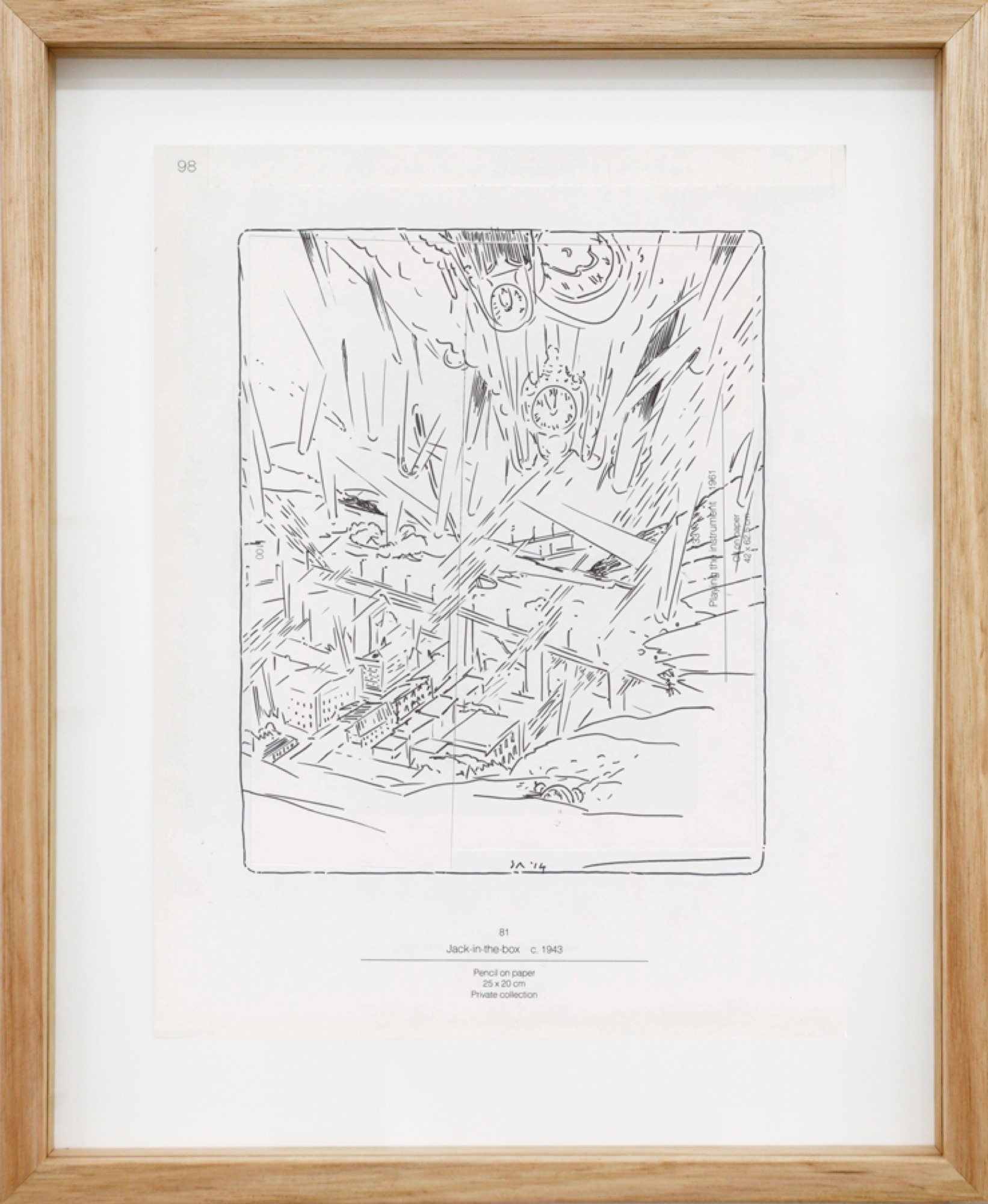

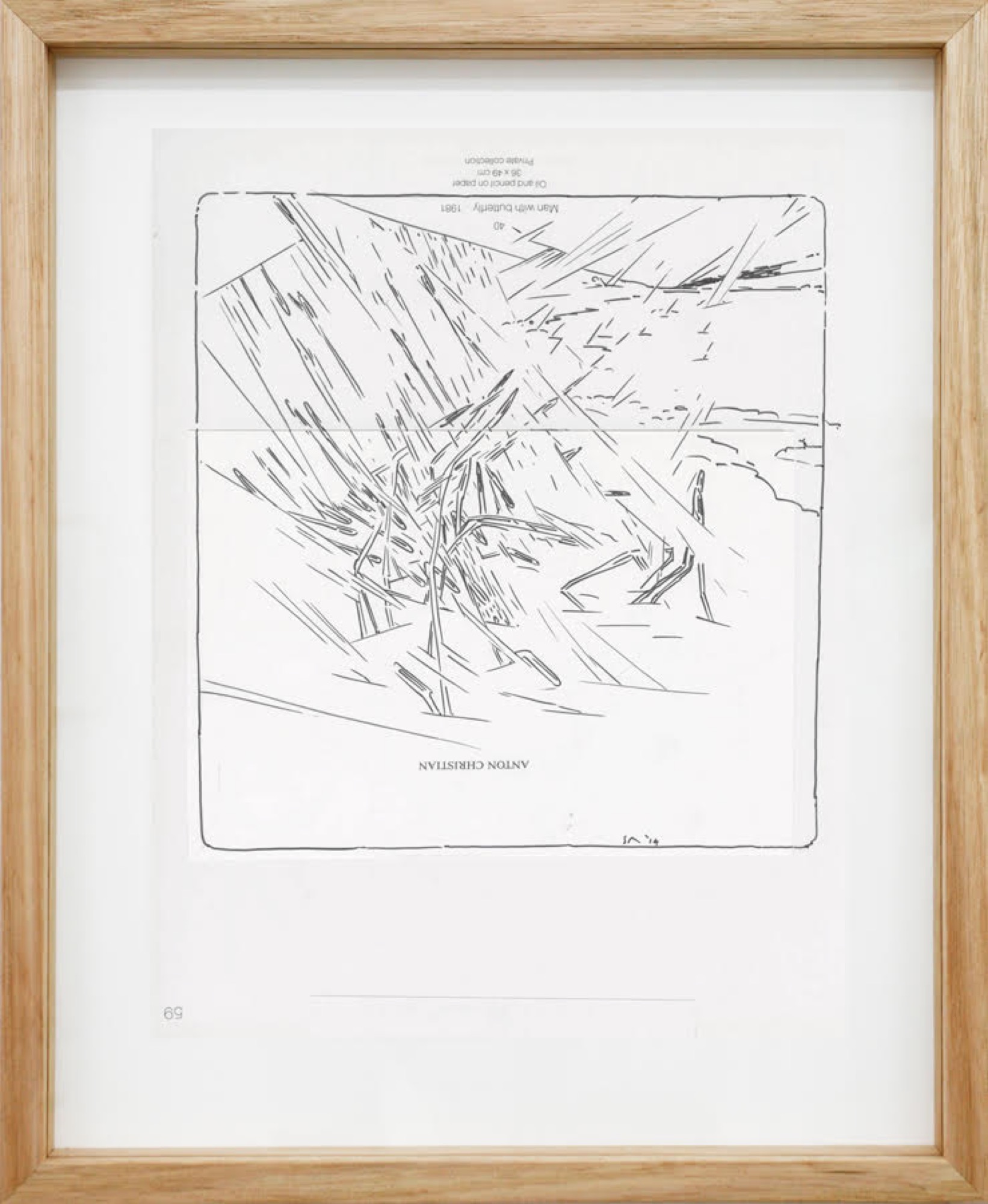

For surrealist artists in the 1920s, collage became a means of creating provocatively disorienting works, and also a strategy for shaking off the protocols of their artistic training. Surrealism aimed to combat the grim mechanics of bourgeois convention by acknowledging and celebrating the unruly impulses such convention represses. In Ringholt’s drawings too, juxtaposition seems to be associated, paradoxically, with explosive disintegration. While their monochrome palette and serial format lends his drawings an air of aesthetic restraint, they depict explosions and violent collisions in the dynamic graphic style of a classic comic. In Page 59, volleys of giant needles hurtle out of the sky, streaming vectored trails behind them that weave the air into a tapestry of trajectories. Ornate domestic clocks also fall from the heavens in Page 98, trailing smoke like meteors as they rain down time-death on to a peaceful town.

Elements of the original Perceval reproductions also surface in Ringholt’s drawings. While I was informed by gallery staff that Ringholt’s use of Fifty Years was due more to the quality of the book’s paper than its content, it is impossible to ignore the breadcrumb trails in the works themselves, which seem to indicate affinities between the two artists’ work. Ringholt’s precise graphic style bears little resemblance to Perceval’s unruly, scrawled and sinuous line. However, his playfulness and the surging movement in the drawings recalls the vigour and joie de vivre of Perceval’s work. Both artists’ works also often teeter between euphoria and violence: the catastrophic explosions in Ringholt’s drawings could easily be interpreted as radiant bursts of light. Similarly, in drawings like Twins and Playing with Twins and Cat, both c.1942, Perceval’s depiction of faces distorted in laughter are equally grotesque and exuberant.

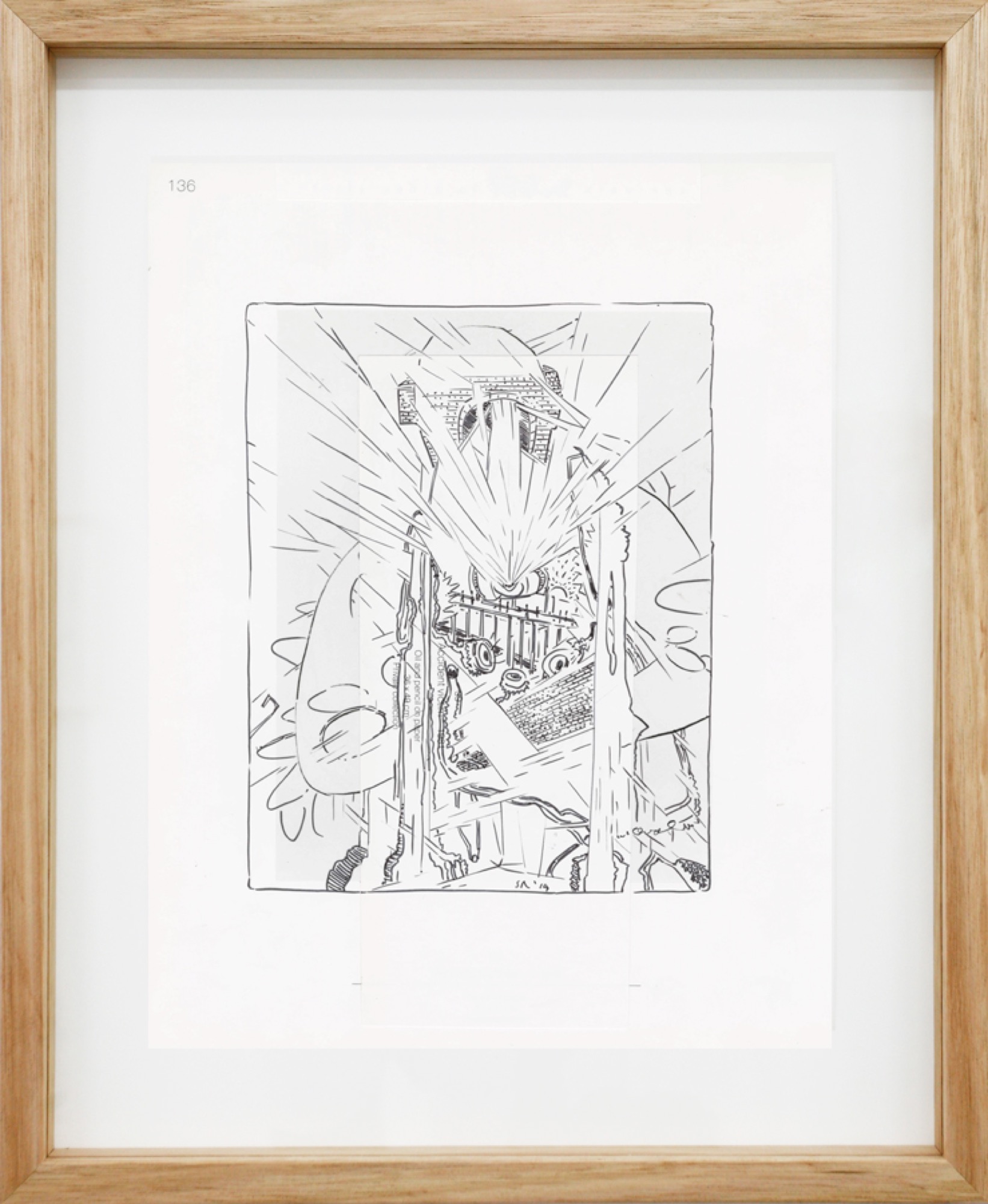

Ringholt’s Page 136 reprises Perceval’s tender portrait of his wife cradling their infant child, Mary and Matthew c. 1946, as a strange composite figure reminiscent of an ‘exquisite corpse’ exercise. Ringholt’s figure borrows Mary’s arms, matching them with a head in the shape of a brickwork rail tunnel and a body perforated with holes emitting shafts of blinding light, like those that radiate from the Virgin’s immaculate heart. The work also wittily incorporates the caption of another Perceval drawing, the odd and dreamlike Accident Victim 1981.

Accident Victim was drawn while Perceval was a patient in a psychiatric hospital, and this detail is key to what, for me, is particularly interesting about Ringholt’s series. The fact that both Ringholt and Perceval experienced mental illness (Ringholt’s experiences are recounted in his 2006 book Hashish Psychosis: What It’s Like to be Mentally Ill and Recover) is, in itself, a fairly banal observation. However, I think that the collage logic of Ringholt’s work acts here as a subtle corrective to social and art-historical conventions around psychiatric illness. The reception of Perceval’s work has been distorted on the one hand by the fetishisation of his illness and his associated categorisation as a ‘tortured genius,’ and on the other by the denigration of the work he produced while unwell. Ringholt’s Page 136 collages together an example of Perceval’s celebrated early work with a drawing from the later period that some have regarded as problematic. The work that Perceval produced during and after his hospitalisation was explicitly excluded, for example, from the 2015 edition of Traudi Allen’s John Perceval: Art and Life, on the grounds that its inclusion would “diminish” the earlier work. With this knowledge, Ringholt’s drawing reads as a restorative gesture, suturing Perceval’s artistic identity back together after its brutal partitioning.

In their eccentric, playful imagery, re-use of found material and collage methodology, the drawings in Works on Paper are clearly related to anarchic surrealist practices, however they don’t share the strident antagonism of 20th-century modernism. Ringholt’s broader project of disorienting normative social codes by acknowledging what they exclude is, as are the drawings in this series, personal and exploratory as well as subversive.

Anna Parlane is a writer and occasional curator based in Melbourne. She is currently finishing a PhD at Melbourne University, and was previously assistant curator at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Title image: Stuart Ringholt, Page 215 (detail), 2014, Ink and collage on offset paper, 31.5 x 24 cm)