Spray Painting The Pioneer

Rex Butler

It has always looked strange to me, hovering up there like some kind of shimmering mirage, but I could never say exactly why.

It’s the last panel of Frederick McCubbin’s The Pioneer, with disputed dates but let us say 1903 to 1905, one of the undeniably great paintings in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria.

How did it end up in the NGV? Now there’s a story.

We all know McCubbin. He’s one of the Heidelberg School Big Four (Big Five if we count Jane Sutherland). He met Tom Roberts when they were both studying at the National Gallery of Victoria School of Design in 1874 and they remained lifelong friends. He started the famous painting school at Box Hill along with Roberts and Louis Abrahams in 1885. Although he wasn’t one of the artists who actually put on the famous 9 x 5 Exhibition at Buxton’s showrooms in 1889, he did have five paintings in the show. He’s the one sitting on the ground with his trademark handlebar moustache drinking tea from a billy while Abrahams cooks steak on a fire while they were up at Box Hill painting one weekend in Roberts’s The Artists’ Camp of 1886.

McCubbin came up with some of the iconic images of Australian “pioneer” life, seemingly swapping what he did in exchange for similarly iconic images by Roberts and another of the Big Five, Arthur Streeton. Thus we have McCubbin’s Lost (1886) and Roberts’s A Summer Morning Tiff (1886), which both depict young women dressed in white wandering alone in the bush. We have McCubbin’s Whispering in Wattle Boughs (1886), which depicts a swagman stretched out in front of a fire, and Roberts’s Sunday Afternoon Picnic at Box Hill (1887), which depicts a young couple stretched out on the grass. And we have Streeton’s The Selector’s Hut (1890), which depicts a man sitting on a log after chopping it down, and McCubbin’s Sawing Timber (1907), which depicts two men in the process of sawing a log in half.

McCubbin for a long time made his living as Master of the School of Design at the National Gallery of Victoria, where he taught amongst others the later-to-be-great Australian novelist Joan Lindsay, author of Picnic at Hanging Rock. (We’ll come back to that connection in a moment.) At one point, he was even Acting Director of the National Gallery of Victoria, and applied for the position of Director. He lost out to the Englishman Bernard Hall, and even though McCubbin continued to work there he never got over the disappointment of not getting the job and relations between the two men were always strained.

Geelong Gallery owns McCubbin’s A Bush Burial (1900), and in 2021 it put on an exhibition entitled Exhume the Grave—McCubbin and Contemporary Art, in which—in that typical revisionist exercise—they found a number of contemporary artists responding to McCubbin’s work as though to bring it up to date. Thus we have Poli Papapetrou remaking McCubbin’s Lost as In the Wilderness (2006), Christian Thompson remaking A Bush Burial (1890) as Dead as a Doornail (2009) and Jill Orr setting her The Promised Land—Still (2012) on the same Yarra River wetlands near Ivanhoe where McCubbin, Roberts and Abrahams once painted. Perhaps the most interesting for our purposes were Anne Zahalka’s two versions of The Pioneer, which reimagined his work not with the classic white Australians settling the country but a series of darker-skinned Europeans arriving with their characteristic objects. And it’s notable that, along the same lines, the art historian Tim Bonyhady writing in the book Exiles and Emigrants describes The Pioneers not as depicting the original inhabitants of the land but in the reverse equivalent of Zahalka as “one of the most influential paintings of the emigrant experience.”

The Pioneer was always an important painting for McCubbin. He had recently moved with his family up to Mount Macedon some seventy kilometres north-west of Melbourne, staying with his sisters during the week so that he could continue to get to work. He writes in 1903 in a letter to Roberts, who at the time was in London, that “I am pegging on at The Pioneer. I feel like the poor devils I am painting in the picture, rather sad about it—however I am doing my best.” But altogether he thought that “it was my best effort in art.”

The Pioneer was first shown in April 1904 at the Athenaeum on Collins Street, along with four years of other work from his time at Mount Macedon. Although the response of both critics and spectators was positive—the reviewer for The Age wrote “A poet in colour is the only description that quite expressed the dominant traits of McCubbin’s art”—The Pioneer did not sell. This was a particular disappointment to McCubbin because he had hoped that the NGV would acquire it through their Felton Bequest—it had recently purchased two works by Louis Buvelot—thus allowing him to go overseas and actually see the work that had influenced him, like his other Heidelberg colleagues. In order to do so, he had listed the painting at the not inconsiderable price of 525 pounds. As he would later write to Roberts, describing the Felton Committee considering whether to buy it or not: “Four or five turned up, they stayed for about four minutes each on the average and went away.” The failure hurt McCubbin, and The Pioneer is said to be not only the last of his grand “history” paintings but also to mark the end of a certain period of his art altogether. The 2009 National Gallery of Australia exhibition McCubbin: Last Impressions 1907–17 begins in 1907, the year after The Pioneer was sold, and says that its subject is McCubbin’s “late style,” which is considerably different from anything that came before.

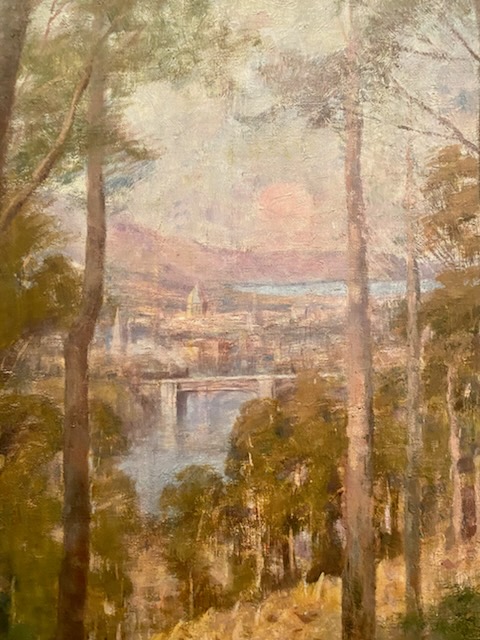

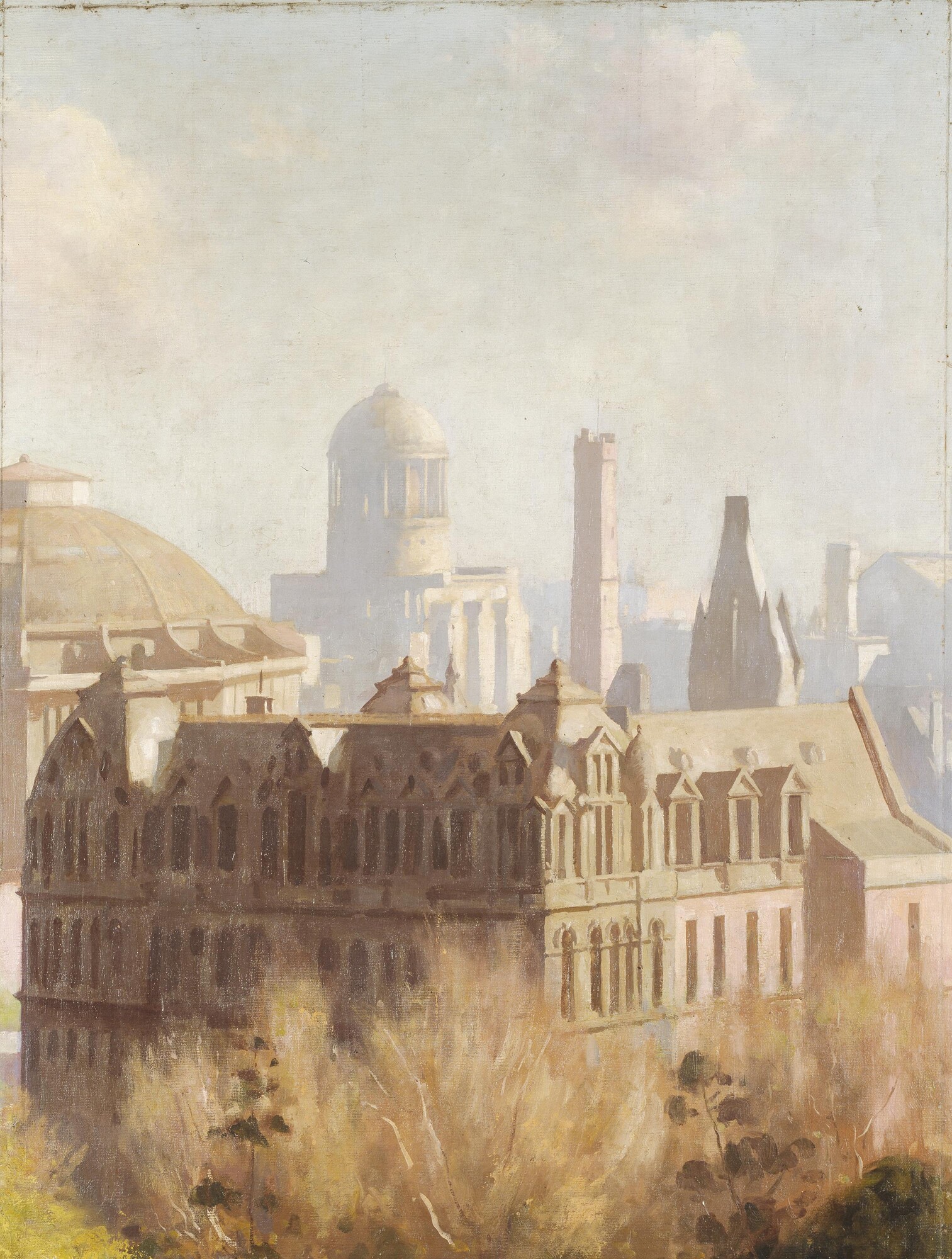

Let us turn now to The Pioneer and ask what we see there. It is indeed much like such earlier McCubbins as A Bush Burial, The North Wind (1891) and On the Wallaby Track (1896) in depicting “settler” life. But over the course of its three panels it seems to tell the story of at least two generations of these settlers. In the left-hand side panel, a woman looks dreamily off into the distance while her husband lights a fire with a tent behind him. In the centre panel, the man now sits on a felled log looking at his wife and child with a small wooden hut in the background. And in the right-hand side panel a younger man kneels at a grave in a much more cleared space with a city shining distantly across the water. We know who posed for the various figures: local labourer Patrick Watson and McCubbin’s wife Annie for the man and the woman in panel one, his artist friend James Edward, Annie and Watson’s nephew Jimmy for the baby in the central panel, and Patrick Watson again for panel three. We also know where McCubbin mostly painted it from: a large estate, “Ard Choille,” owned by his near-neighbour at Mount Macedon, the BHP chairman William McGregor. In fact, as with Monet’s haystacks, McCubbin painted the three enormous canvases en plein air, even just like Monet digging trenches in the ground so that he could get to the top of them (NGV curator Michael Varcoe-Cocks has even discovered residual traces of the soil in which they were originally buried at the bottom of the canvases), although it has been suggested that the sharpness of the figures in them indicates that they must have been painted back in McCubbin’s studio.

Of course, the question often asked is, who is that younger man in the right-hand side panel? Is he, as seems obvious, a son burying one of his parents, thus making him the baby of the central panel, or is the painting meant to evoke a longer time-span, thus making it more an allegorical depiction of Australian “pioneers” altogether? This second reading appears possible because one of the enigmas of the painting—and this is where we came in—is the swiftness and incongruity of the city suddenly appearing in that right-hand side panel. Yes, we have trees being cleared and a log cabin being built in panels one and two, but now there’s this whole glowing, glistening city rising up over that hill behind.

The artist Helen Maudsley in a beautiful essay “McCubbin’s Different Dimensions,” written for the Last Impressions exhibition, makes the point that these three panels put together form something of a square, and she furthermore notes—a wonderful formal observation—that there’s a sort of diagonal running from bottom left to top right across the three panels, which furthermore goes from the front of the picture plane out towards the back. And that mystical city up high and receding in depth represents for Maudsley a kind of “resurrection” or let us even say “heaven” to which that figure buried and mourned in the foreground might ascend.

In another brilliant essay on McCubbin, “The Phases of McCubbin’s Art,” the pioneering German-born first woman curator at the NGV or any Australian gallery, Ursula Hoff, describes that new style in which the city is painted in the following terms: “Flecks of paint unrelated to the form of the object represented combine at a distance into an atmospheric impression.” She then goes on to echo the observation of earlier critics that it is painted “in the manner of Turner,” whose work was beginning to exert an increased influence on McCubbin and which he was about to see for the first time when he travelled to England in 1907.

And it is at this point that things get interesting. As we have seen, McCubbin originally exhibited the work in 1904 at the Athenaeum Gallery, hoping to sell it to the Felton Bequest. The selectors were not impressed, and after getting over his disappointment he took the advice of his artistic colleague Walter Withers, who suggested that what they were looking for was more a “celebration” of Melbourne. And so McCubbin repainted what was originally there, and this is what we now see. It is often said that he made what we view there up, but I would want to suggest that what we have is a version of the Falls Bridge, which he had previously painted in 1882, and a version the Royal Exhibition Building, which he knew very well. His friend Roberts had a studio there for two years while he was painting his so-called Big Picture, depicting the opening of the First Parliament of Australia, which took place there in 1901. Indeed, his oldest son, Louis McCubbin, would later paint it in 1924—a work that is mistakenly attributed to McCubbin himself by art historian Anne Galbally, so much like the version of it in The Pioneer does it look. And for all of the seeming implausibility and anachronism of seeing the Exhibition Building from a place that still needed to be “pioneered,” it must be remembered that visitors could once take a hydraulic lift up to the promenade around its dome and take in amongst other things a view of Mount Macedon, and we suggest that McCubbin simply reversed the perspective and it is now the Exhibition Building that is seen from Mount Macedon. There it is, floating impossibly in space, as though somehow—and here is where I might disagree with Maudsley—in front of the rest of the painting, replacing that humble wooden hut with its brick, steel and slate and representing as much as anything the “death” not “resurrection” of that “pioneering” lifestyle as the country is sucked into the city.

But McCubbin’s changes worked, and the next time the painting was exhibited at the Victorian Artists’ Society Winter Exhibition in July 1905 for sale at the considerably cheaper price of 367 pounds it was purchased by the Felton Bequest and entered the collection of the NGV to become one of its best-known and most-loved works, something that like Roberts’s Shearing the Rams can never be taken off the wall, no matter how unconventional the hang.

The Art Gallery of Western Australia also owns a classic McCubbin, Down on His Luck (1889), featuring another great Australian founding myth, that of the unsuccessful gold prospector, which had previously been taken up by S.T. Gill and was later to be the subject of a famous photograph by Nicholas Caire, depicting a luckless gold digger sleeping rough in a tree whose insides he had hollowed out with an axe. But on 19 January this year two protestors acting on the Disrupt Burrup Hub campaign, ceramic artist and illustrator Joana Partyka and Ballardong Noongar man Desmond Blurton entered the gallery, laid an Aboriginal flag on the floor and spray painted the logo of Woodside Energy on the glass in front of the painting using a stencil. Partyka then glued her hand to the side of the painting while Blurton spoke against Woodside’s “ongoing desecration of sacred Murujuga rock art” at the Burrup Peninsula in the Pilbara, some 1200 kilometres north of Perth.

Of course, all this could be seen as part of the wider series of climate Extinction Rebellion protests taking place around the world, in which activists have defaced or otherwise attacked famous works of art to draw attention to their cause. Thus in London yellow paint was thrown at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888), in Canada maple syrup was dripped down Emily Carr’s Stumps and Sky (1934), and at the NGV’s The Picasso Century show in October last year two protesters unfurled a banner reading CLIMATE CHAOS = WAR + FAMINE in front of Picasso’s Massacre in Korea (1951), and both glued their hands to the sides of the work.

Partyka was arrested for her actions and altogether fined $7,458 at a subsequent court hearing. She later said outside the court “I have always taken full responsibility for my actions, which is more than I can say for Woodside.” For their part, Woodside said it “respects people’s right to protest peacefully and lawfully,” while banking a profit of $9.7 billion last year, thanks in part to the dramatic rise in energy prices due to the war in the Ukraine. (Just this week in the papers, there was discussion of a special windfall tax being imposed in such circumstances, in response to which Woodside insisted that the “existing tax system is working as it should.”)

When McCubbin’s great-granddaughter Margot Edwards was asked what their great-grandfather would have made of protestors using his painting to draw attention to Woodside continuing to expand its operations in the Burrup Peninsula, thus endangering Indigenous rock art, she insisted that he would entirely approve. “He would have laughed out loud and supported this very clever protest, which has not harmed his painting in any way and has opened up an important conversation.” And his great-great-grandson Ned Reilly went on to say, “as a family of engaged artists and scientists, the statement made in this protest is totally in line with the McCubbin family’s rich legacy of using art to make comment on urgent environmental issues.”

And it is here that we return again to where we began, for what might it mean to suggest that McCubbin’s The Pioneer is already its own protestor graffiti? That that city he added after he originally completed the painting is like a kind of empty glowing corporate logo spray painted onto the work?

For, indeed, the gesture of those two protestors spray painting the Woodside logo onto Down on His Luck is quite ambiguous. There is certainly a brilliantly ironic contrast between a failed gold miner and a corporate behemoth that recently banked several billion dollars in profit. But as every corporate image consultant will tell you, it is never a bad thing to have your image splashed everywhere. And the truth is that corporate sponsorship underpins all art and art institutions today, as Natalie Thomas has been telling us for years. And, as if to make this clear, just a few weeks after stencilling the logo of Woodside on McCubbin, other protestors spray painted it on the front doors of the Western Australian Parliament, reminding us all of the extraordinary power such corporations exert over our democratic politics and politicians.

To go back to The Pioneer one last time, that image of Melbourne there, that floating pink city, attached at the very last moment, can appear like a corporate logo of Melbourne, which of course is underpinned by the same extractive practices as Woodside and would spell the end not only of those “pioneering” immigrants but also threaten the Wurrundjeri Woi Wurrung peoples who came before them and whose way of life is perhaps also being mourned in that right-hand side panel. Indeed, to us the image can appear almost “hauntological” in that it is not only about the death of a certain past but also the fact that a certain future will not come to pass. (Oh, and that Joan Lindsay connection: one of the inspirations behind hipster theorist Mark Fisher’s notion of the “hauntological” is the famous excised last chapter of Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock, in which the lost schoolgirls and their teacher enter a time portal and pass over into an alternative reality.)

If The Pioneer could once have been read as the prophesying of a triumphant future while commemorating the past, it can now be seen as an image of the corporatisation of Australia and the precarity of our future in a time of unprecedented climate change. And if McCubbin could once have been regarded as one of the great creators of national myths, he can now be seen as his own first protestor spray painting a corporate logo on top of his own painting. Who is that being buried in that right-hand side panel? All of us as we busily extract the minerals to build that huge edifice behind him. It hovers there like another dimension, but unlike the schoolgirls of Hanging Rock who are never seen again, for us there is only this place where we live.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.

This review was made possible thanks to the generous support of MERIDIAN SCULPTURE.