Some voices carry

Lydia Mardirian

I first encounter Arini Byng’s exhibition Some voices carry on the PHOTO22 website when scrolling through the long list of participating artists. I look over the many names, pausing here and there to view images by the featured artists, previewing their take on the festival’s theme “Being Human”. My cursor hovers over Byng’s name, an image appears and my eyes linger a while. I’m overcome with an opaque feeling and my internal mutterings simmer. The image is a black and white photograph of a young girl walking from the sea balancing a frisbee filled with water, heading towards another girl and a man, who are bent over and kneeling on the sand. They are occupied by some activity, which we can’t quite see as it’s cropped out of the frame. To the right of them stands a white man holding a towel. While I am guilty of favouring photographs like these, of candid snapshots, I find this photograph particularly stirring. And so, I jot down that the show begins on the 29th of April. The day comes and up to level 8 of the Nicholas Building I go.

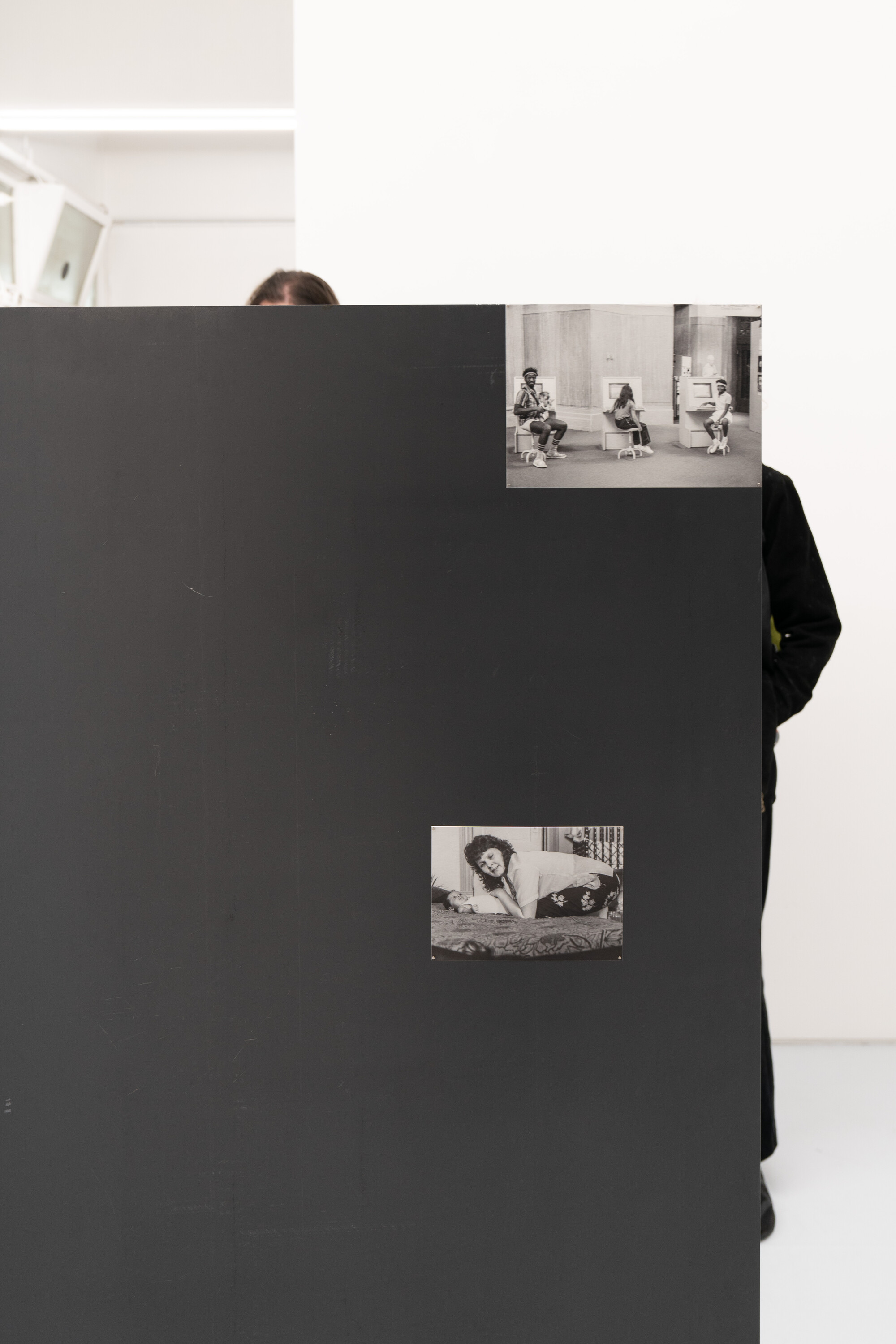

Walking into Caves, I’m greeted by many more of these black and white snapshots. While three are framed and mounted on the gallery walls, the rest float on thin, dark steel structures that occupy the centre of the two gallery spaces. The screens, which reference Byng’s father’s birthplace of Pennsylvania, once the hub of steel manufacturing in the United States, appear to me like pages of a photo album. Though, while photo albums require the hand to animate them as a site for touch, for tender strokes, for indexical points and page turns, my body now assumes this activity. As the steel structures hide particular photographs from sight, to view this series you need physically to move around the steel, as if mimicking the turning of an album page. Similarly, the body is at times hidden by these structures. In this way, areas of closeness and occlusion are concomitantly created in this public space, which is e/affective because the show is, after all, comprised of the artist’s family snapshots.

While talking with Byng, I learn that her mother came across a stack of family photographs held together with an elastic band, which she then posted to Byng. These colour photographs, which the artist hadn’t seen before, were then scanned, revealing the dirt and scratches on the photographs’ surface. Likely the outcome of time and past interactions, family photographs are artifactual objects that record and participate in social life. For this exhibition, Byng recoloured and rescaled each photograph. We can speculate that this was done to rejuvenate the prints, render them in a way that aligns with a particular aesthetic sensibility, or perhaps the process was an act of apprehending a familial past. In any case, the humble family photograph is reframed as an art object. Although perhaps only on visual, formal terms—the intimate narrative of which the imagery speaks persists. And, as I go on to describe, this is important.

The exhibition catalogue essay penned by Byng informs us that the photographs were taken by her Anglo-Celtic Australian mother and Black American father during the mid-1980s and early 1990s in the United States. We can say that, like most snapshots, the photographs presented in Byng’s show were initially taken to capture memorable moments, filled with joy. As a third party, viewing these photographs, I would categorise them as vernacular, shots taken from everyday life by a non-artist. These photographs reside on the periphery of photographic history, whose centre is occupied by fine art photography, taken by trained photographers. While the fine art photograph is a medium of aesthetic singularities, distinct periods and styles, vernacular photographs are aesthetically repetitive and ubiquitous. Indeed, these photographs pose a problem to an art-historical taxonomy precisely because they are defined subjectively, through intimate determiners, by those whose eyes through which they were viewed and whose hands through which they passed. And so, when photographs like this, which usually live in frames on a desk, in albums, shoeboxes, or on the fridge, enter a gallery space, how are they to be viewed and comprehended?

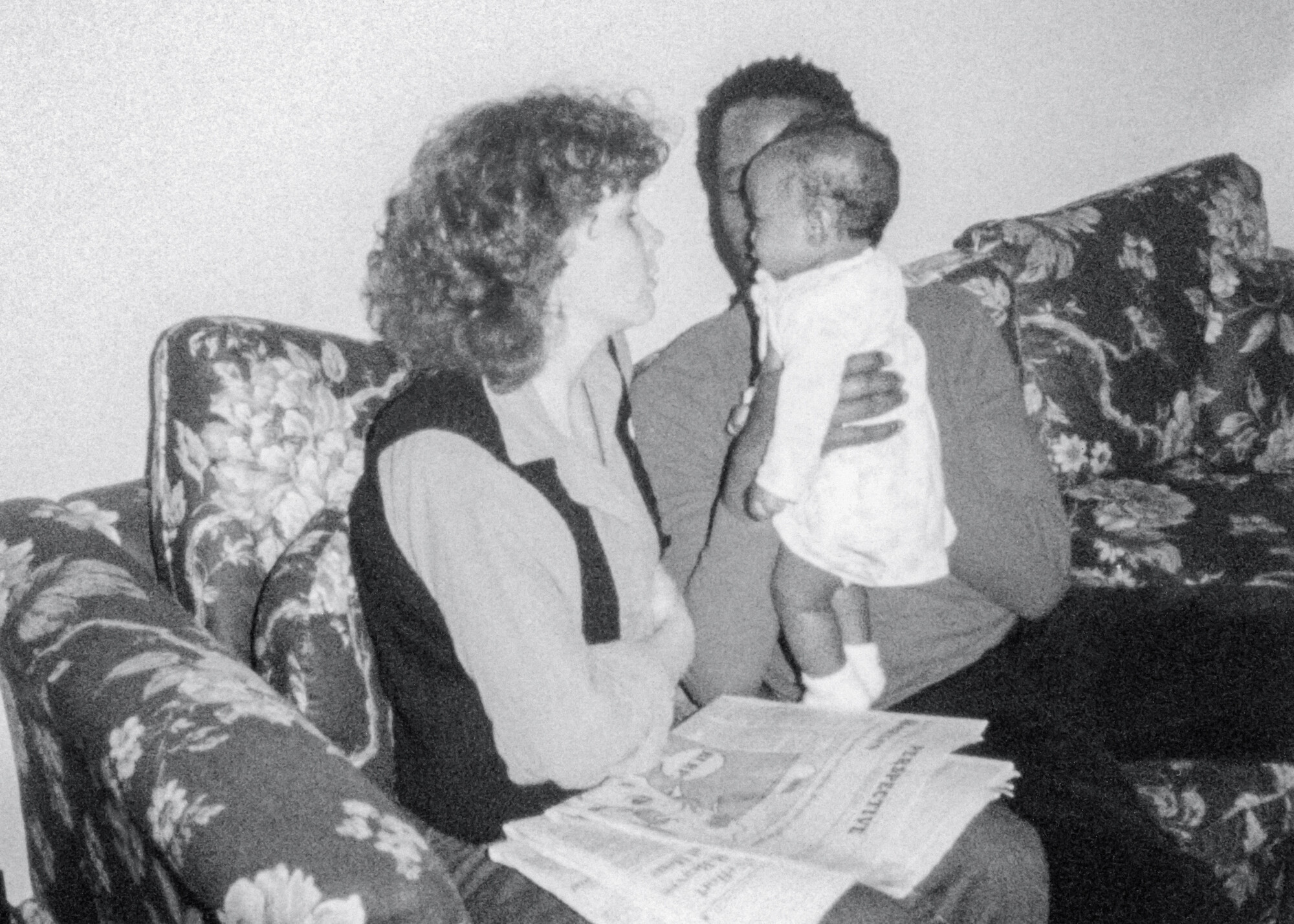

Often when vernacular photographs enter the public arena, they become deracinated from the lifeworld to which they once belonged. Put differently, they no longer circulate in their intended sphere and are divested of their initial significance. The difference here, however, is that Byng’s photographs are not estranged from those who understand their value, they are not found photos. Indeed, as Byng introduces me to the photographs, subjects and narratives are identified and recalled. As such, I not only become acquainted with the photographed subjects, but also the moments that sought to be remembered. I learn, for example, that the subjects in Held who sit on the floral couch are in fact her mother and her father, and the baby they are holding is her cousin. I also know that her aunt was likely the one who took it. In other words, the intimate knowing that so characterises photographs of this kind still remains. And by reading the narrative-driven exhibition catalogue that includes familial anecdotes and descriptions of some of the photographs, this intimate knowing is not only valued by the artist but is something she seeks to transmit. We learn, for example, that the subjects by the sea are Byng’s cousins and uncle, and that this family outing to Virginia Beach was the last before her parents moved to Australia. We learn that her father was unsure whether the white man on the right of the photograph was squinting due to sun’s glare or in disapproval of a mixed-race couple.

In the artist statement, Byng writes, “the only way back is through her parents’ camera lens”. As a member of Armenian and Lebanese diasporas, I know very well that a way to glean the familial past rooted elsewhere is possible via photographs; as I wait for my grandma to tub my serve of the kousa mehshe she cooked, the weight of her periwinkle blue photo album rests on my lap. My hand traverses the album pages and I move back… I move back to Aanjar and the moment baba picked an apricot from one of the many trees at the family house; I move back to Beirut and view baboug standing at the steps of L’Hôtel Saint George, about to start work. Turning the sheet, I return to Aanjar and move back to the moment of Nene cooking the rabbit baba and amo hunted earlier in the day. Every time I visit my nene in Noble Park and look at these photographs, I move back to my family’s home.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes, “Photography has something to do with resurrection”. For Barthes, this link with resurrection derives from a hallucinatory temporality opened up via the photograph’s indexicality. The photograph stands as both an “emanation of its referent” and a unique timestamp of a “that-has-been” whose presence it captures and carries. The photograph, in other words, collapses temporality by maintaining a moment since gone. Notably, the photographs that comprise the show are around thirty to forty years old, and many were taken before Byng was born. In other words, these photographs are not necessarily a means to re-ignite and re-present the artist’s own family memories, but rather a means to reach that which is otherwise seemingly intangible to her. Indeed, viewing the photos within my grandma’s album (which are from the 1960s and 1970s) doesn’t simply affect me because I have the intimate knowledge of faces and narratives, but because there is an emotional program, a yearning to participate in a culturally particular familial world. So, while the gallery becomes a site of resurrection—these past moments captured by the photograph are brought into the present by virtue of collapsed temporality—it may also become a prism through which the artist can establish proximity. Though, only she knows the intensity of this distance and the potency of how it feels.

It is precisely in this cultivation of intimacies that the political resonance of this show is vocalised. I pluralise intimacy because, on the one hand, the re-presentation of these photographs seems to be a way for the artist to recover culturally and racially specific family connection, which again only she can know and feel. Indeed, as I wrote earlier, while the steel structures establish areas of closeness within the gallery, they also occlude. On the other hand, these family snapshots re-presented by Byng are visual articulations of subjectivity within the everyday, the space where individuals negotiate their selfhood between the discrete events that structure a society. Crucially, the vernacular photograph is never an artefact in isolation, it is always suspended in a matrix of signification and historical inflection. And the white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy (thank you, bell hooks) in which we live has rendered this violently the case for black and indigenous bodies and people of colour. Photography has been (and continues to be) utilised as an apparatus to aid systemic racism by affixing racial categories through the visual documentation of these bodies as subordinate and without selfhood. Yet the artist does not present a strident counter discourse. Instead, Byng presents photographs of candid self-articulation and tender expressions of connection. One of the photographs that encouraged me to consider the multi-accentual intimacy of the exhibition is the only photograph within it that features Byng, Dance. While adults sit on the ground of what appears to be a living room, immersed in their own conversations, kids dance: one has their back towards the camera, another is putting on sunglasses whilst in motion, and at the centre is Byng, dancing hand in hand with a family member who looks down towards her, as she, wearing a beaded necklace, glances towards the camera. The visualisation of “(af)filiation” (to borrow Tina M. Campt’s combination of the two words) does not simply occur because subjects are visually tied together due to appearing within the same frame. Rather, love and linkage are communicated via the haptics of united movement and touch. Inter-subjective feeling is concentrated in Byng’s photographs and it continues to atomise throughout the gallery, registering in many ways and rendering the show so profoundly e/affective.

The invocation of sound within the show’s title is seemingly incongruent for the silent medium of photography. Indeed, I commenced this review describing how at the sight of Byng’s photograph my mind quietened. But Some voices carry communicates intimacies in family and community across disparate geographies and temporalities. Go look through the aperture Byng shares with us, which is so often rarely circulated, and take in these tender and ever so elegiac reminisces, these semiotically loaded photographs that are salient sites of culture.

Lydia Mardirian is an Armenian-Lebanese arts worker living in Naarm, who sometimes researches and writes. She has worked as an assistant researcher for the University of Melbourne, where she helped to develop an art history course on photography. She currently tutors art history at the University of Melbourne.