Tom Roberts: Shearing the Rams

Rex Butler

I was recently showing a friend from New Zealand through the Australian collection at the National Gallery of Victoria and we came, of course, to Tom Roberts’ Shearing the Rams (1888-90). You have to get there eventually because everything in the collection and its arrangement on the walls points you that way. The work is visible — and intentionally so — as you step into the first of the rooms devoted to Australian art, past the depictions of Tasmanian Aboriginal people by Robert Dowling, through the room dedicated to early colonial landscape and into the room featuring a selection of work by Melbourne-based landscape artists from around the time of Roberts’ masterpiece.

There it is next to Jane Sutherland’s Numb Fingers Working (1886) to the left and Isaac Whitehead’s A Spring Morning near Fernshaw (1880) to the right. Behind you as you look is Ugo Catani’s Lover’s Walk, Mt Macedon (1890), and filling out the space and providing some sort of backstory are Frederick McCubbin’s Home Again (1884) and Roberts’ own Going South (1886).

The painting itself — since its well-documented cleaning by the NGV in 2006 for its Australian Impressionism show, which removed layers of discoloured varnish and overpainting — is always brighter than you remember it being. The shirt of Jim Coffey, the gun shearer at the front of the painting, is pinker. (It is such an astonishing colour, with its feminine associations, for such a famously masculine painting.)

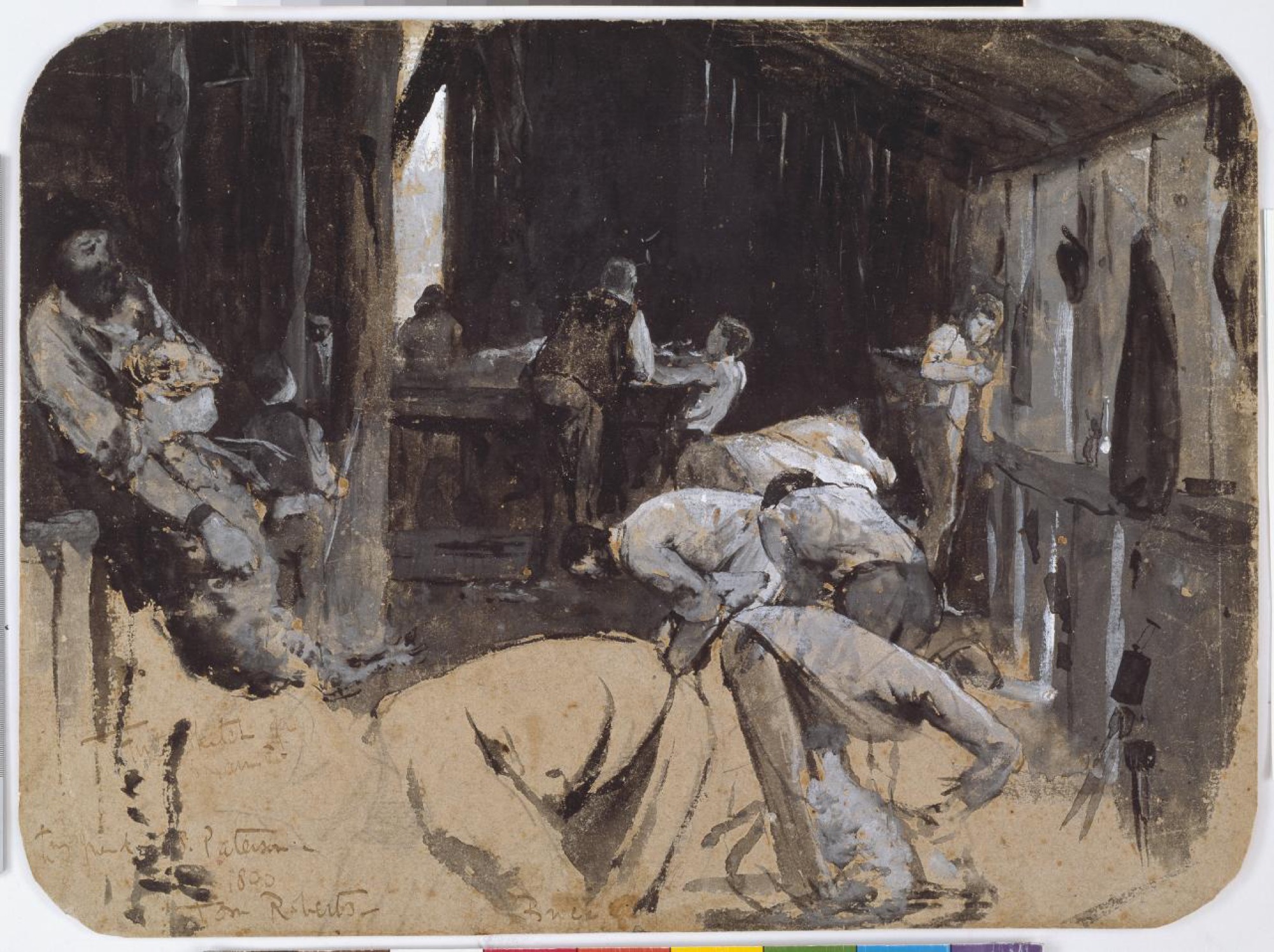

I take my New Zealand friend through the painting, familiar to me from years of Australian Art History lectures. There is its much-remarked spatial organisation, slowly arrived at by Roberts after 2 years of reflection and some 80 preliminary sketches in gouache and pencil, with the series of perspective lines running through the canvas meeting not at the brightly-lit door at the entrance to the shed where we might expect, but immediately to the right of the shearer standing up drinking water from a billy at the back. There are the brilliant and surprisingly little commented-upon axes of temporal organisation running perpendicular to each other: the short-term from front to back, with the faster and younger shearers towards the front and the slower and slightly older towards the back; and the long-term from left to right, with the teenage rouseabout taking the fleece away to the left across the shearers at the height of their powers at the centre to the retired shearer counting sheep and smoking a pipe to the right.

There is the extraordinary doorway at the back with its tripartite division of the Australian landscape into three stacked levels one on top of the other: green grass at the bottom, brown eucalypts in the middle and blue sky at the top. It’s like a miniature Sid Nolan Wimmera Landscape or Fred Williams Upwey Landscape, which is to say it contains in a nutshell the next 70 years of Australian art.

(To me at least, it’s always had this other, unwanted but revealing association. Many years ago, I was invited by Juan Davila to visit his house. After a perfectly pleasant lunch, he led me downstairs to see his studio. Of course, I was expecting something Hannibal Lecteresque, with red paint spattered on the walls, porn mags scattered on the floor and maybe an actual dead body or two. Even more terrifyingly, it was immaculately tidy, with his tubes of paint lined up in order, his brushes freshly cleaned and a half-completed painting hanging on the wall. It was Nothing if Not Abnormal (1990), his scabrous and defamatory depiction of the power struggle — homosocial, of course, the result of a love affair gone bad — between Bob Hawke and Paul Keating. It’s the painting in which Keating, dressed up in a leather corset and in homage to one of the prostitutes of Demoiselles d’Avignon, turns his head around, parts his buttocks and blows a loud fart at the audience. As I gazed in wonder at this vision from over the other side of the room, Davila standing next to the painting beckoned me over with crooked finger to inspect it more closely. “Have a look in Paul Keating’s arsehole”, he whispered. I leant forward nervously and saw something extraordinary: a miniature Fred Williams landscape up there. And now I can never look at that thin slit of Roberts’ doorway — the entrance, after all, to the same kind of homosocial space — without thinking of Davila’s painting.)

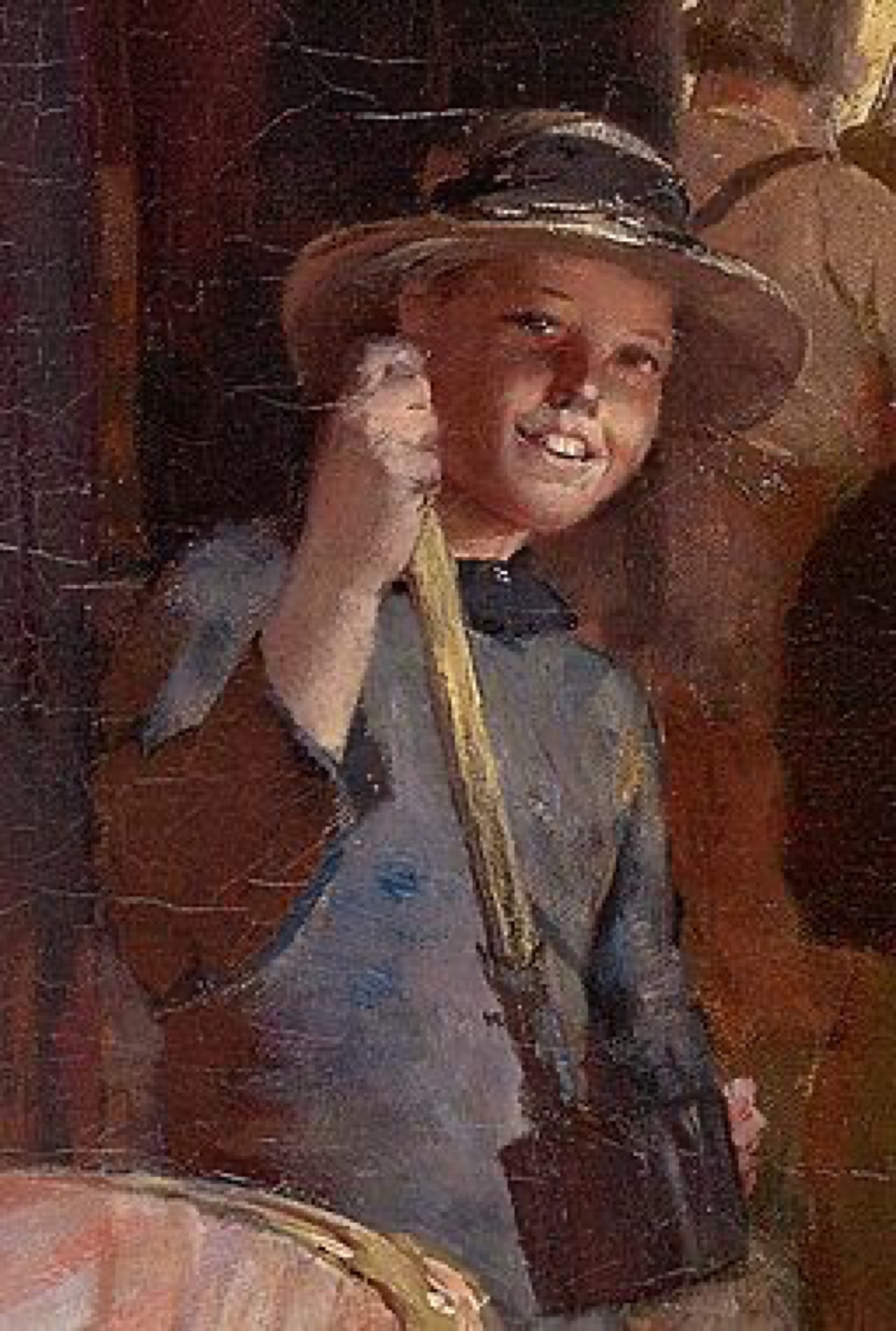

Needless to say, I mentioned none of this craziness to my New Zealand friend, who’s a perfectly sensible art historian himself. But this time, looking at Shearing the Rams, something else caught my eye, as it increasingly has these past several years: not the blaze at the back of the painting, but almost its opposite, the small boy holding the pot of tar and plunger at the centre.

Both this young boy and the slightly older rouseabout holding the fleece to the left, alternately said to be in the pose of Esau in Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise or the young boy holding the stone in Courbet’s The Stonebreakers, were added at the last moment to Roberts’ otherwise carefully composed canvas, as the surviving sketches and X-rays taken during the cleaning of the work reveal.

But what has gradually emerged over the past 20 years of study of the painting is that the little boy holding the tar pot is in fact a girl. Indeed, the model for the figure is known. She is 9-year-old Suzie Davis, who apparently truly did have the job of covering up any cuts in the sheep with tar and was paid sixpence by Roberts to “kick up the dust” to create a hazy atmosphere while he was painting at Brocklesby Station, and whom Roberts originally painted when he did add her with a broom.

There is a wonderful article in the Age newspaper corresponding with the NGV Impressionism show revealing that Davis had in fact lived on the station for her entire life, originally telling Wangaratta pharmacist and ABC stringer Charlie Henshall in 1963 of her presence in Roberts’ painting and testifying to the fact that, as against the emerging idea that Roberts largely completed the work back in his Collins St studio after making preliminary sketches on site, much of the painting — including the addition of Suzie — was done en plein air, as the presence of Roberts’ brushmarks on the timber panels of the original woodshed, one of which was kept by Henshall before the shed was lost to fire in the mid 1960s, demonstrates.

But what is the meaning of this young girl holding the tarbrush and catching our eye at the quiet centre of the painting, I kept asking myself? (And it was increasingly being speculated, against previous scholarship, that she was even the model for the slightly older boy to her left holding the shorn fleece.) Why did she seem after all the hidden secret to the painting?

And then it clicked. Roberts’ late addition of first a girl with a broom and then turning that broom into a tarbrush was a last-minute nod to the act of painting his picture — which Roberts had great hopes for, speaking of wanting to capture “the quick running of the wool-carriers, the screwing of the presses, the subdued hum of hard fast working and the rhythmic click of the shears, the whole lit warm with the reflection of Australian sunlight”. That tin into which she is about to dip her brush in order to seal any small wound inflicted by the shearers on the sheep is strikingly like the palette and paintbrush Roberts used to make his painting.

In fact, the Courbet painting we might best compare Shearing the Rams to is not The Stonebreakers but The Wheat Sifters, in which two women sift wheat from chaff using sieves, leaving a thick red residue on a canvas sheet, in what can obviously be read as an analogy to the act of painting and them as stand-ins for the painter, with art historian Michael Fried in his analysis of the painting even comparing the woman on the left to the painter’s inert left hand holding the palette and the more active woman on the right with her back turned to us to the painter’s right hand holding the paintbrush or knife.

Indeed, I’m even tempted to suggest — if we can say that Suzie, now with her hair cut off as it was originally stuffed under the tarboy’s hat, also serves as the model for the boy on the left — that the boy holding the fleece is supporting the canvas while the girl in the centre is painting it. After all, if the comparison with The Wheat Sifters is to be followed, then all of the shearers are something of stand-ins for the painter and his ambitions for the painting in their unself-conscious absorption in their work and their lack of awareness of anything and anyone outside of the shed. Roberts’ great image of “strong masculine labour, the patience of animals and the strong human interest” only works, finally, because the men in it are stand-ins for the painter and the painter a stand-in for the men. In other words, what we are actually looking at in Shearing the Rams is nothing les than the various stages in the long process of Roberts making his painting.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.

Title image: Tom Roberts, Shearing the Rams (1888-90), oil on canvas, 119.4 x 180.3 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Felton Bequest, 1932.)