Shaun Gladwell: Homo Suburbiensis

Tara Heffernan

One constant in a world of variables

A man alone in the evening in his patch of vegetables

— Bruce Dawe, “Homo Suburbiensis” (1964)

I’m not sure what it means to anyone, the title, but I like the Latin kind of reflection on the suburban human. But also, it’s a poem that, um, an Australian poet wrote that, you know, means a lot to me personally. So that’s the kind of reason why I use that title.

— Shaun Gladwell, “The Drawing Room with Patricia Karvelas: Running Away with Shaun Gladwell”, ABC Radio National (2021)

Australian artist Shaun Gladwell rose to fame just over two decades ago. Maintaining an international presence since, his work is typically lauded for its incorporation of urban subcultural practices, art-historical references and stunning cinematic quality. Homo Suburbiensis, currently on display at Anna Schwartz Gallery, continues these investigations, but there are crucial differences. Accompanied by a selection of paintings, a new video work of the same name provides a more probing exploration of the body and its physical limits.

Homo Suburbiensis (2020) opens with a close up of Gladwell’s face as he applies a nasal strip (an adhesive band designed to keep the airways open) to his nose. The narration begins:

Here is the human. Here is the human. Here is the SUB-uUrr-BAN human. We will see the SUB-uUrr-BAN human functioning. We will see the SUB-uUrr-BAN human functioning … This is how an ear looks. This is a pair of knees. And here, a foot …

The screen shows corresponding images of Gladwell, who plays the “suburban human”. Activities like moving, jumping, and dancing—all actions that can be performed by the human with little effort or ambiguity—are listed, as if they are automatic features being advertised to the viewer. In the scenes that follow, we see Gladwell running—the most prominent activity in the film—balancing a BMX on a kitchen bench, eating and practicing yoga. The video work samples the voiceover from the cult short The Perfect Human (1967) by Danish director Jørgen Leth. In Gladwell’s version, which is the same length of Leth’s original film (13 minutes and five seconds), the audio has been minimally altered by Kazumichi Grime. The most obvious distinction, a warped, robotic “SUB-uUrr-BAN” is dubbed over the word “perfect”. Like the characters in the original black and white film, Gladwell performs actions in sync with the narration, occasionally deviating in humorous ways. In one scene, for example, Gladwell eats McDonald’s out of a crumpled paper bag rather than the simple home-cooked meal described by the narrator. In another, when the narrator details the act of undressing, he descends into a frenzied dance in the middle of an unruly street party, resembling a rehydrated Warren Ellis with his flailing limbs and billowing beard.

Decades after the original film’s release, Lars von Trier—one of the leading figures of the Dogme 95 movement—challenged Leth to remake The Perfect Human five times, resulting in the experimental film/documentary The Five Obstructions (2003). A reference to this film emerges at the end of Homo Suburbiensis: an intertitle reading “The Sixth Obstruction”. Known for his visceral depictions of human suffering, von Trier’s influence might also be identified in the way Gladwell represents the body in this new video work, which is unique to his oeuvre. In Homo Suburbiensis, unlike other works, there’s a strong emphasis on facial expressions, which are shown in great detail in slow motion, particularly in the scenes showing Gladwell running. Every pore and hair follicle is visible. Made explicit in these close-ups of strained expressions and sweat is effort—the thing that is hidden, or at least obscured, in Gladwell’s iconic earlier work. As Rex Butler aptly summarised in an exhibition text from 2007, a key feature of these works was the feigned effortlessness behind the incredibly skilful actions performed by his subjects, achieved with poise and grace which belies the subject’s talent (“what used to be called sprezzatura”, Butler explains). The focus was youth-oriented sports with high aesthetic payoff. Physical limits were pushed to display the stunning capabilities of the human body, perfected through rigorous training regimes. For example, the iconic Storm Sequence (2000) displays Gladwell performing balletic skateboarding manoeuvres in slow motion while waves crash in the background. Pataphysical Man (2005) shows a breakdancer spinning on his helmeted head, the image inverted so it looks as though he is suspended in the air. Conversely, running is an exercise undertaken to maintain the body and the mind—the aesthetic payoff of which is getting a lean bod. While the discipline might be admirable and images of joggers in advertising might be upheld as examples of living well, the act itself isn’t inherently attractive. Exercise is a unique act, as the American cultural critic Mark Grief notes, in which “one does formerly private things, before others’ eyes, with the lonely solitude of a body acting as if it were still in private”. The extreme close ups show the artist’s face contorted and strained, howling silently: these are raw and often ugly expressions often associated with pain and release.

While not as comically didactic as Leth’s script, the pacing and formulaic structure of the narration reminded me of This Day Tonight (1967-1978), one of Australia’s first current affairs programs. Based on the format of a long-running BBC program, it matter-of-factly documented the lives of different “ordinary” Australians, including, for example, the Chinese New Year celebrations of Chinese-Australian families in Sydney broadcast in 1969, the domestic life of a lesbian couple broadcast in 1970 and the daily routine of a working-class Melbourne family, headed by a factory worker, broadcast in 1977. These rather candid segments were essential in capturing the texture of Australian life. Recently resurfacing online thanks to ABC’s RetroFocus, today these grainy segments appear rather quaint. Their over-simplified stories told in that funny, lost middle-class Australian accent, derivative of BBC English, evoke a mix of nostalgia and perhaps cultural cringe. However, there is something appealing about the earnest attempt to consolidate the stories of those represented.

Gladwell lifted the title Homo Suburbiensis from a 1964 poem by Bruce Dawe, an Australian writer remembered as the “poet of Suburbia”. As Australian author Kevin John Brophy lamented upon Dawe’s death in 2020,

New themes of gender, ethnicity, identity politics, the explosion of poetry since the avant-garde experiments of Fluxus might seem to leave Dawe’s poetry suspended in a historical moment, but this is to say no more than what happens to every strong and distinctive poet.

There’s no doubt that Dawe’s poetry is “of its time”. As indicated by Brophy, the stories of “average” people—blue or white-collar workers who occupy the suburbs and the regional and rural areas of Australia—hold less weight today. Not merely are these stories eclipsed by issues of race, ethnicity, gender and identity, but often, ordinary people are regarded with contempt. Beasts of Suburbia: Reinterpreting Culture in Australian Suburbs (1990) a collection of essays edited by Sarah Ferber, Chris Healy and Chris McAuliffe, confronts this issue directly (and importantly, explores the cultural and economic diversity within Australian suburbia, a reality that is often neglected in portrayals and critiques that focus on whiteness). As they note in the introduction, the identifiable disdain present in much commentary on the suburbs is propelled by “intellectuals … seeking to delineate the suburbs.” Not only does this further the divide between the cultural elite of inner-city creatives and media-types (who today almost exclusively come from wealthy backgrounds), but it also helps alienate a large, though widely dispersed, part of the population, making them susceptible—as Ghassan Hage and Shannon Burns have respectively noted in White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society (1998) and ‘In Defence of the Bad White Working Class’ (2017)—to dangerous conservative discourses that appear to address their grievances and acknowledge their identities. The popularity of the term “Aussie battler” on mainstream programs like A Current Affair and morning infotainment news might typify this pattern.

Despite the explicit reference to the “suburban human”, Gladwell doesn’t appear to be in the burbs in the video. Some exterior scenes show Melbourne’s cityscape in the background. These appear to be shot in Melbourne Cemetery, located in Carlton. A very cool and culturally active inner-city suburb, Carlton is known for its cafes, bars and Cinema Nova—a far cry from the typical vision of suburbia. When we think of the suburbs in an Australian context, we generally mean the outer suburbs—sparse places, facilitated by generic shopping complexes, fast food joints and dying main streets, cul-de-sacs, endless blocks of generic homes divided by fences and spacious backyards full of plastic furniture and the detritus of family life. Iconic onscreen depictions include television programs like Kath and Kim (2002-2007), which is set in the fictional suburb of Fountain Lakes (the suburb Patterson Lakes, 35km southeast of Melbourne, served as the primary filming location); or, more grittily, films like Geoffrey Wright’s Metal Skin (1995), set in Altona (13km south-west of Melbourne CBD); or Abe Forsythe’s Down Under (2016), a black comedy following the aftermath of the Cronulla riots. When I mentioned this obvious disjunction to a friend, they quipped that Melbourne probably seems suburban—and embarrassingly provincial—to an internationally celebrated artist. Perhaps! However, I suspect that, in this context “suburban human” is a term used to describe “the everyman”. Especially in an age where the experience of the suburban subject is largely ignored or homogenised, it is a term that might seem non-descript enough to reflect a generic—and perhaps a broadly relatable—human experience.

Dawe’s poem, which details the everyday routine of a man living the suburban dream, describes him tending to his garden. “A constant in a world of variables”, the garden seems to be a space in which the suburban human regains a sense of control in his life.

The choice to represent the body undertaking exercise—while consistent with Gladwell’s established obsession with the human form—inadvertently highlights a disjunction between Dawe’s time (booming post-war Australia) and ours. While the suburban quarter-acre dream still exists, life is generally more transient today. Many people rent for longer, are confined to apartments, travel for work, or find their lives too busy to focus on the cultivation of a garden. The body and the mind, on the other hand, have become more significant sites for improvement. Various technologies—apps, tracking devices, online diaries and programs—help set goals, measure progress and map successes. While running is a common example—and doubtlessly, one that is common for those in, or approaching, middle-age (like Gladwell)—it is also analogous with various forms of “cope” (internet slang for “coping mechanisms”) adopted today: recreational drinking and drug taking, MMA, yoga, dancing, wellness, witchcraft, gaming, etc. Pursuit of these hobbies, sports or subcultures—which vary depending on socio-economic status, race, gender and sexual orientation—help build community and create meaning and routine in lives that might be otherwise chaotic or sparse. Like Dawe’s post-war protagonist in his back garden, there’s solace to be found in these preoccupations.

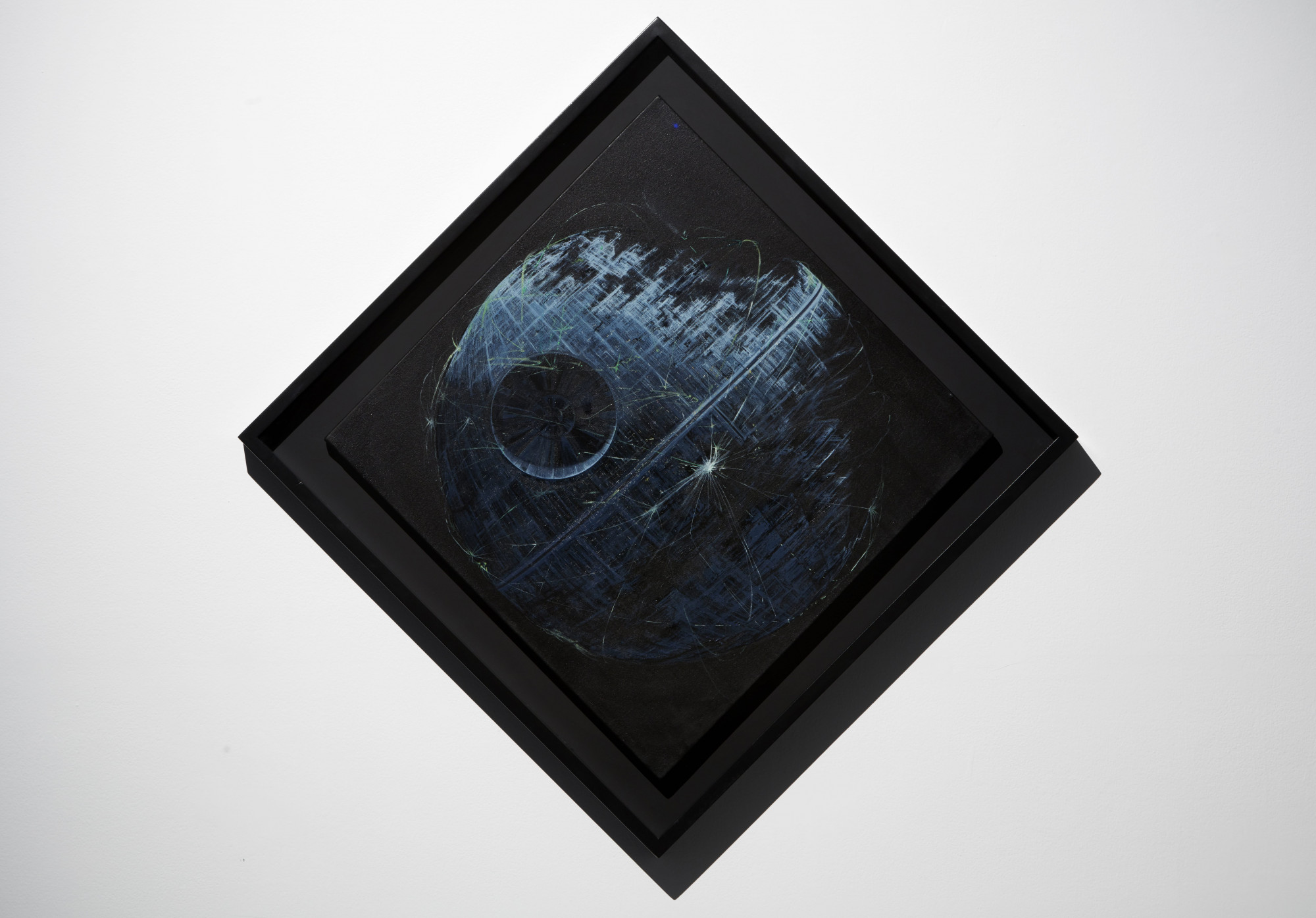

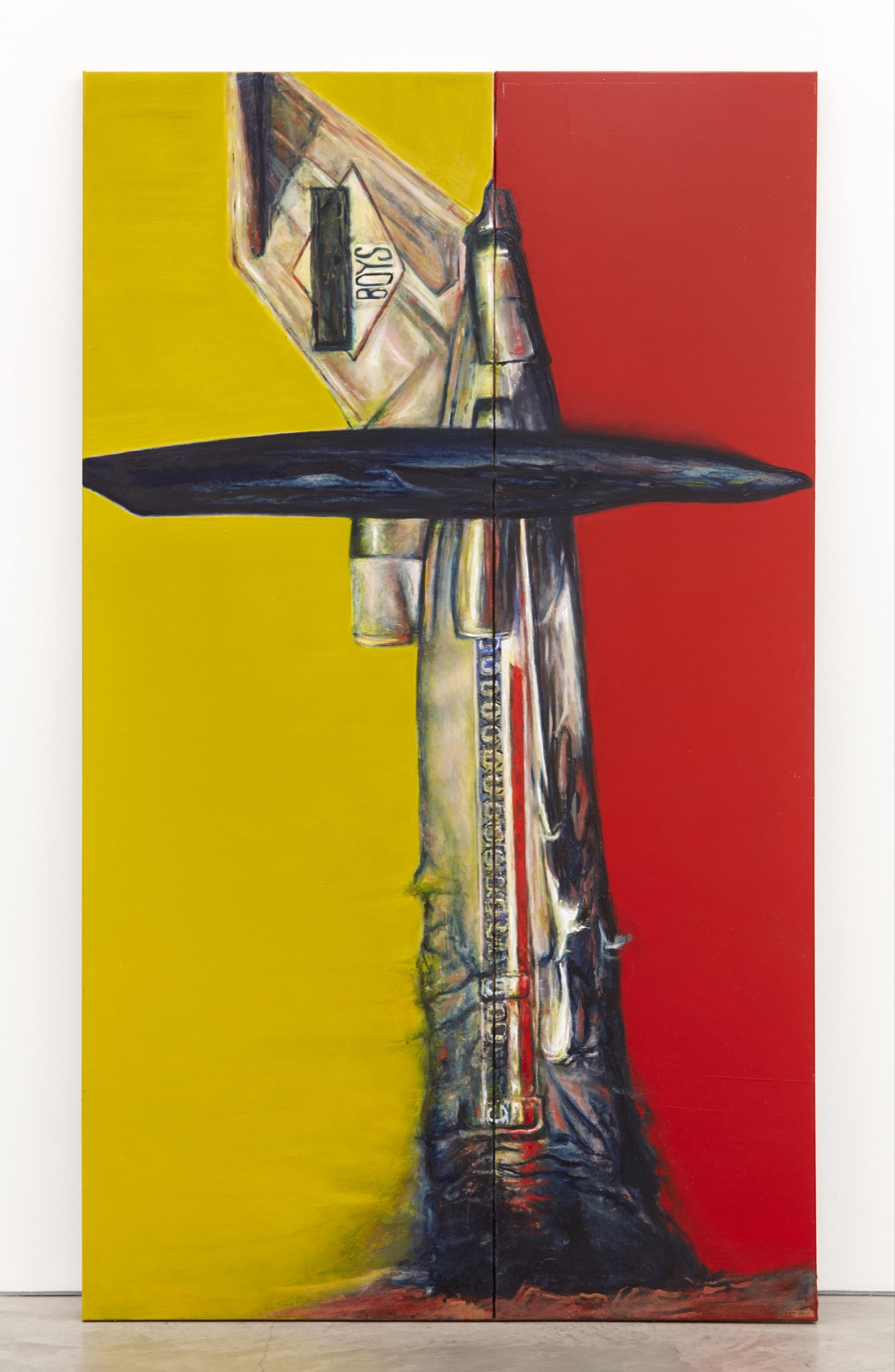

While the paintings in the exhibition seem rather disjointed—their scumbled surfaces and bulky presence are jarring next to the slickness of the video work—there is a visual and thematic link. It’s worth noting that it’s difficult to imagine Gladwell’s paintings as stand-alone works. While he painted in art college, Gladwell is not known for his work in this medium and is often referred to as a “video artist”. In this instance, the paintings seem more like props complimenting the video work. Quite quaintly, there are skateboard wheels attached to the bottom of one canvas and most are leaning against the wall rather than traditionally hung (a subversion of convention that is now a convention itself, like extending a painting onto the gallery wall or attaching a prop to the canvas in an arte-povera-like gesture). Alone on the wall by the entrance to the main gallery space, visible in the background while you view the video work, is a painting of the Death Star (the galactic superweapon from the 1977 sci-fi space opera Star Wars). The Last Imperial Death Star / regional, national and international routes (2021) is hung on an angle, like one of Piet Mondrian’s lozenge paintings. The synthetic polymer and oil painting is the most refined in the show. From a distance the spherical shape, rendered in sharp chiaroscuro, resembles a baroque skull, or piece of fruit. Another painting, BOYS (2021), is similarly copied from a pop cultural reference: the cover art from the Beastie Boys first album Licensed to Ill (1986). The original image of a Boeing 727 private jet crashing into a mountain, resembling an extinguished joint, is turned 90 degrees counter-clockwise in Gladwell’s rendition, dissecting the aircraft down the middle. The dissection, the blocked colours and the awkward framing (the crushed nose of the aircraft/joint is crumpled at the bottom frame, while the top fin extends just beyond it) seem to be making a joke on the picture plane—again flexing Gladwell’s art-historical knowledge. Both are images iconic of 1970s and 80s popular culture, importantly corresponding with Gladwell’s childhood and teenage years. Both are objects of cultural consumption that are associated with dedicated fan bases. Both reference fantasies of total destruction.

In an interview with Patricia Karvelas for ABC Radio National, Gladwell explains that he read Dawe’s Homo Suburbiensis in high school. I suspect that he chose the title partly because he has read very little since—at least nothing that’s touched him in the same way. Like Star Wars and the Beastie Boys, he likely encountered the poem at a formative moment. This might sound like a slight, but it’s not intended that way. For better or for worse, most people don’t read. However, what is more disheartening is that often the most vocal advocates of a “reading culture” are boring, self-satisfied, middle-class liberals who fawn over young adult fiction and derive their politics from the tepid dribble produced by milquetoast media outlets like The Guardian or SBS Viceland—an unempathetic cultural elite with no appreciation for subtlety or complexity, and a barely cloaked disdain for ordinary people.

As Leth’s original film progresses, things get stranger. The actions don’t correlate with the narration. The movements of the “perfect human” become more frantic and less robotic. The “perfect human” speaks, asking “Why did you leave me? … Why is fortune so capricious? Why is joy so quickly done?”. These phrases are spoken in Danish, which is sampled and captioned in Gladwell’s film while he munches on McDonald’s. We learn that, apparently, there is no perfect human. People are not robots, but emotional, fallible and perishable. Accordingly, from the beginning of Homo Suburbiensis, we are reminded of death. Many of the most visually arresting scenes of Gladwell running are shot in a cemetery, the stunning ornate gravestones and monuments jutting out around him echoing the silhouettes of high-rises in the cityscape behind. It’s didactic, yes, but Gladwell does cliché very well. You might say that he’s running from death, but he’s also literally running through it.

Tara Heffernan is a PhD candidate (Art History) at the University of Melbourne. Her thesis concerns the work of post-war Italian artist Piero Manzoni—specifically, the political and cultural dimensions of his employment of humour and transgression in relation to capitalist aesthetics. Heffernan’s broader research interests include class politics, feminism and the lineages of modernism and the avant-gardes in contemporaneity.