Sélection de Paresthésie Prestige

Audrey Schmidt

While chronic paresthesia is a neurological disorder, temporary paresthesia is a common occurrence. Also known colloquially as a limb “falling asleep”, the pins and needles sensation generally manifests due to pressure on a nerve or poor circulation caused by bodily idleness. Ander Rennick’s solo exhibition at Mejia, Sélection de Paresthésie Prestige, translates as a “selection of prestige paresthesia”.

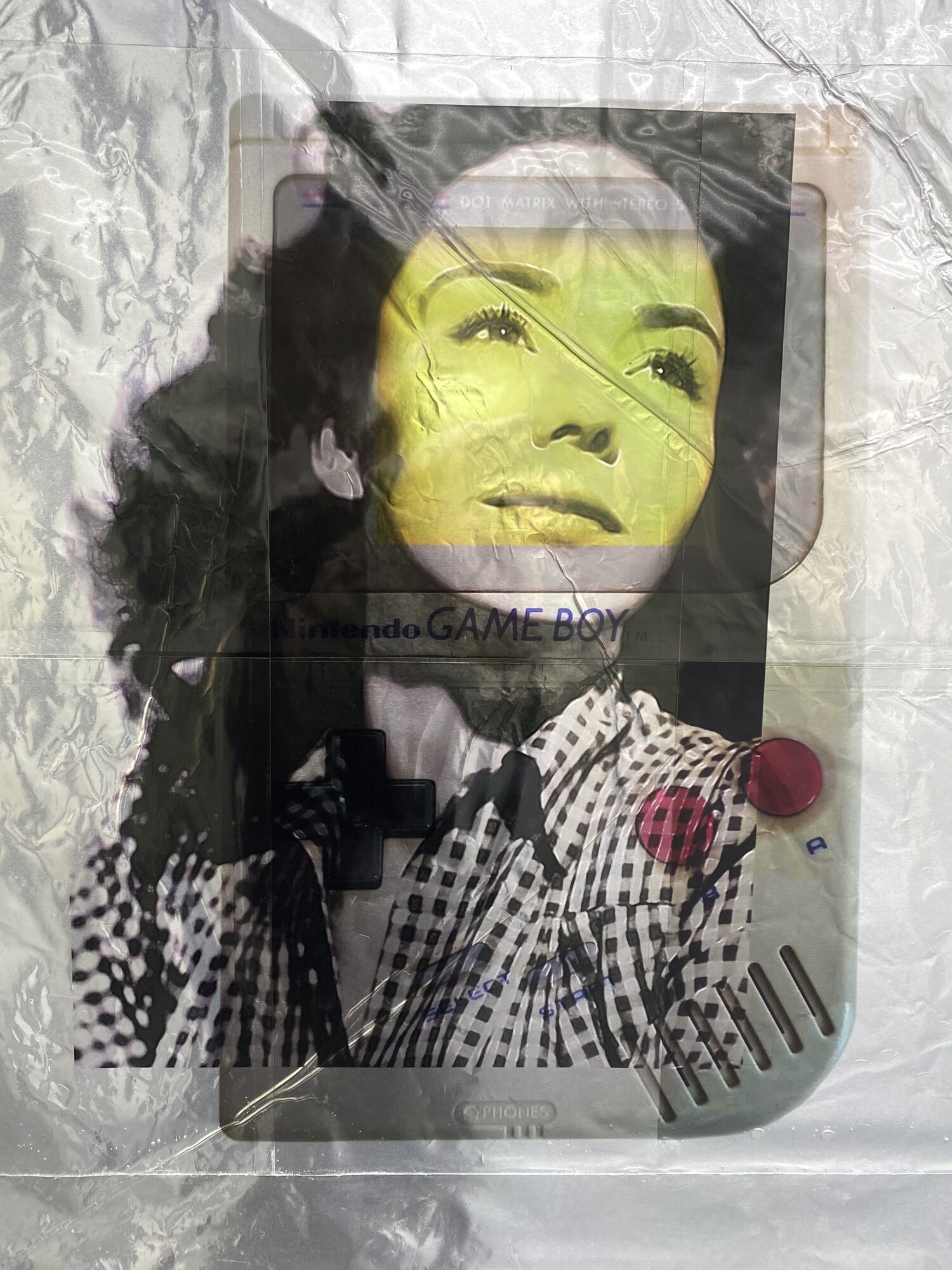

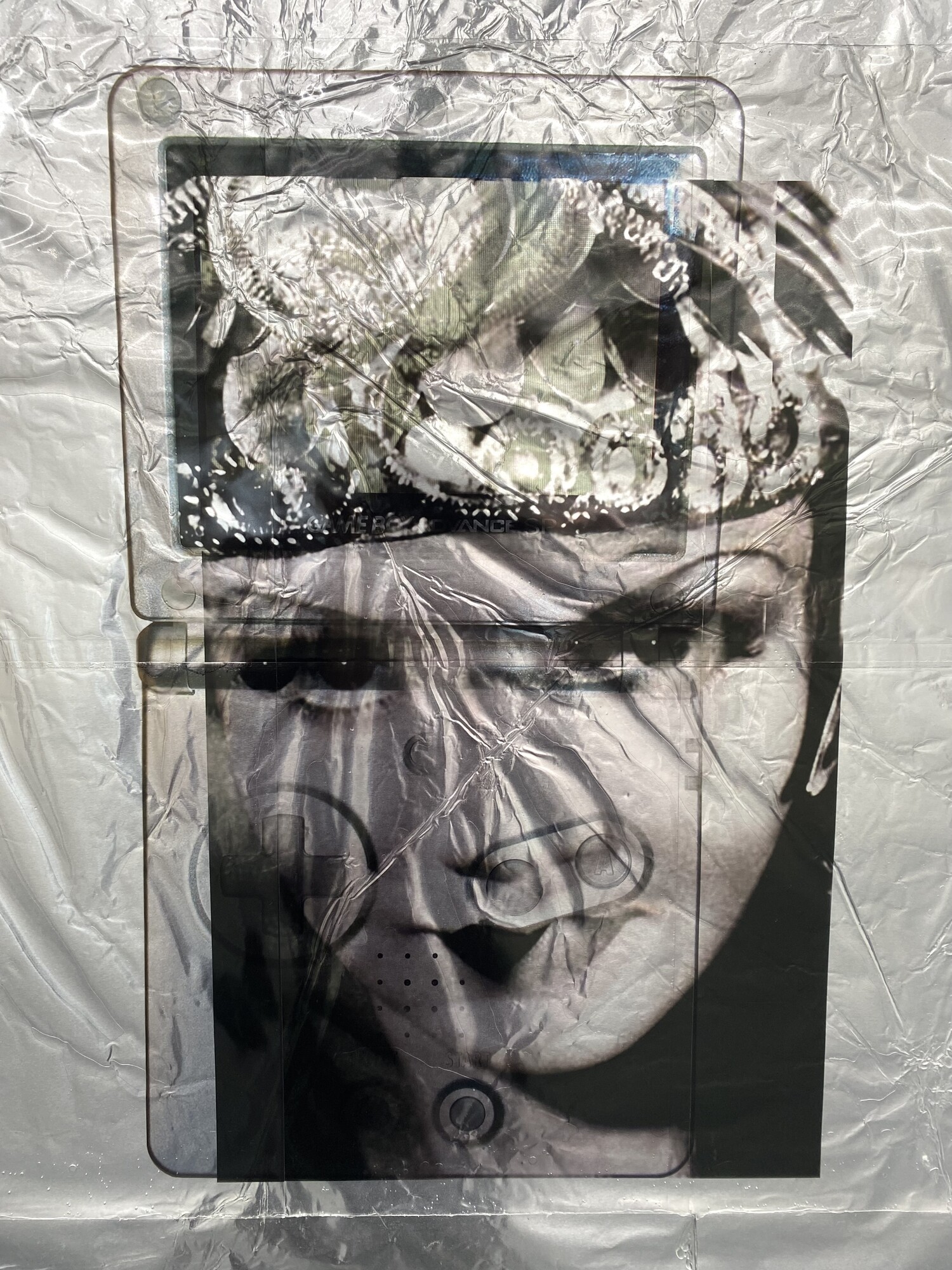

Lining the walls is a collection of composite images fusing the archetypical femme fatale greats of paranoiac noir fused with an almost-complete catalogue of Nintendo handheld consoles, from the Game & Watch released in 1980 up to the most recent Nintendo Switch in 2017. Joan Crawford in Possessed (1947), Jennifer Jones in Love Letters (1945), Bette Davis in Dark Victory (1939): these characters all represent instability or madness as it manifests in the oneiric inability to distinguish between unreality and reality. The gothic themes of these films centred on the fears associated with the medical gaze, the psychic illness of desire and the home as it was beginning to break apart and atomise as women developed increased autonomy in the spheres of work, consumption and relationships.

Like the women featured, the gaming devices are vintage, nostalgic, collector’s items—portals to a numb and comfortable unreality. I can’t pretend to know anything of their provenance or function, but what’s clear is that Sélection de Paresthésie Prestige is first and foremost a game of associations. The materials of these works themselves represent a childhood regression or transference: aluminium foil, contact book covering, inkjet transparencies (a now almost obsolete classroom projection tool), all glued together with craft glue that has trapped wet bubbles under their surfaces. They fling the utility of primary school craft materials, sliced and lubricated, into the realm of brute adult sexuality as a fetish (as though they were a rubber bib or teat). The theatrical graphic style is experienced as an aftereffect, glow, residual or “lagging” aesthetic response that, without the animating principle of light and motion, render the “silver screen” comatose, caught between life and death.

As though designed to assist a hypnotic regression session, Blue Corridor (2021) by Shiho Yabuki played on loop in the gallery on opening night. The soothing, meditative sounds of binaural beats and alpha wave 1/f fluctuation music (thought to stimulate nerve relaxation) is recognisable as the kind of “healing music” one might hear in therapeutic environs such as the Calm app, a YouTube sleep meditation or kindergarten nap-time. The title of each of the femme fatale works mirror the wellness undertones of the exhibition: Promesse de Bonheur or “promise of happiness”. Stendhal wrote that “beauty is nothing more than the promise of happiness”, and the beauty industry has always been keenly attuned to this promise with further promises of instant gratification. Each of the Promesse works is distinguished by an English word in brackets after this phrase including Verity, Caprice, Acuity, Wealth, Solitude, Stupor, Safety, Mimicry, Face, Pod, Chastity. They read like cardinal virtues that take us closer to a wellspring of beauty. Declared boldly like categories one might expect to hear in a vogue ball (“she’s serving Caprice”). They also resemble “chapel perilous” states and necessary red herrings one passes through on their journey to a higher consciousness (stupor, chastity, pod).

The first “Promesse de Bonheur” on the room sheet, Promesse de Bonheur (Verity) (2022), features Jennifer Jones in Love Letters (1945). Jones plays an amnesiac thought to have killed her husband and represents the only smiling face in the exhibition. The others show emotionless faces in glamour shots or movie promotion stills. In a state of preternatural calm, their heroic statuary seems to stand in defence of numbness and sensory death—a withdrawal into the dream world in opposition to waking life. The only facial expression truly recognisable as “happy”, however slight, belongs to the amnesiac, and ain’t that the truth. Similarly, for narrative and tutorial purposes, many video games begin in states of amnesia, frequently intervened by a feminine archetype who will fill in contextual details for the story and help orient the player’s user interface and controls. These include the winged-faery assistant Navi in The Legend of Zelda or Halo’s Cortana and extend to more nefarious Artificial Intelligence Goddesses like Alexa and Siri who respond to all sorts of contemporary forgetfulness.

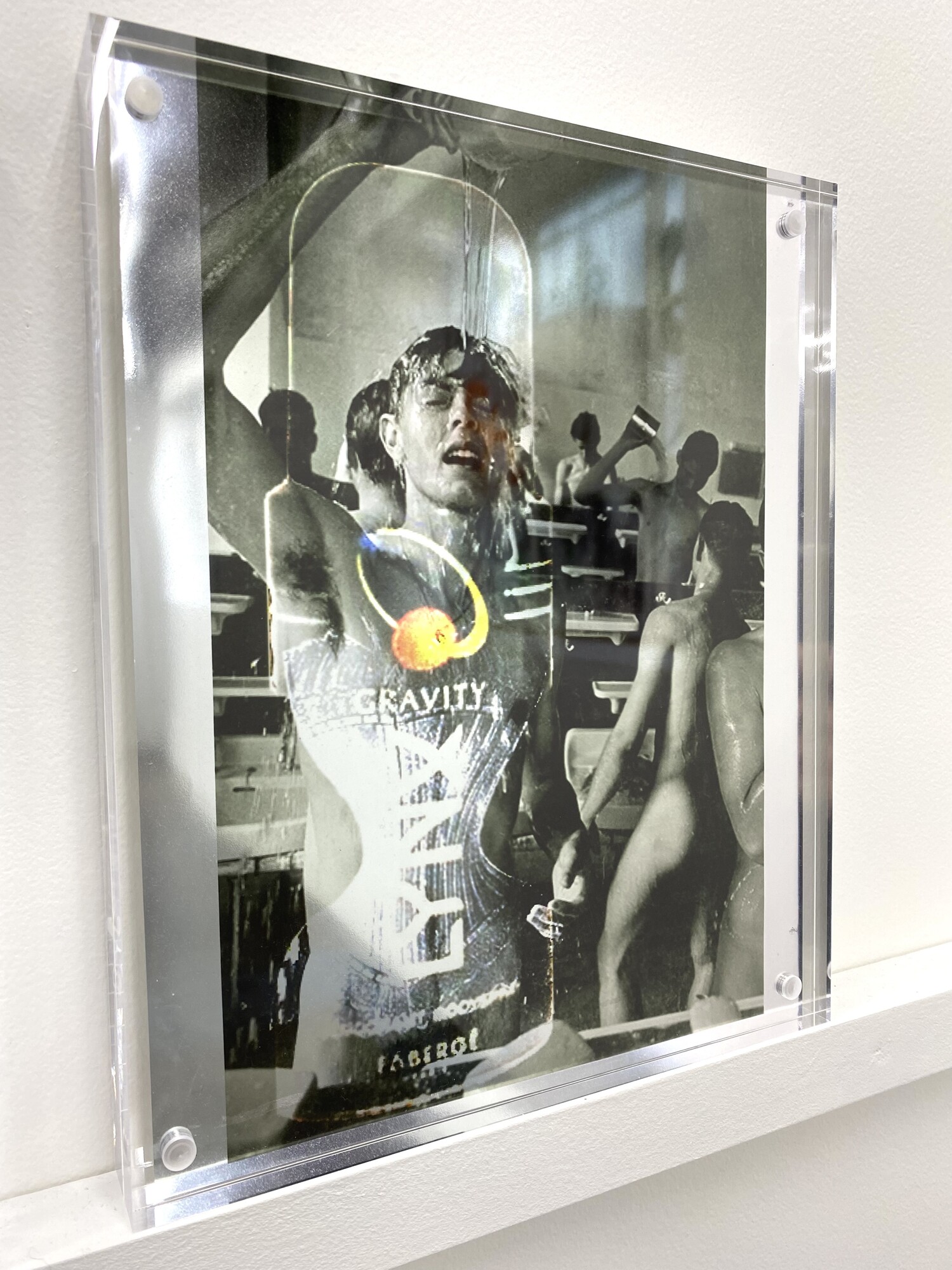

The femme fatale is popular in the homosexual imaginary as she destabilises or frustrates the traditional representation of the onscreen heterosexual couple. She is typically a villainous and supremely seductive archetype that is aligned with the representation of homosexuals as they are each sexual deviants—a threatening “social evil” as unfettered vessels of desire that primes the palette for their fetishisation. This is the first connection I make when I encounter the trio of smaller works in Rennick’s exhibition: Lynx Corset (Young Voodoo), Lynx Corset (Naked Gravity) and Lynx Corset (Fresh Gravity). Unlike the others, these works appear in perspex acrylic magnetic blocks, reminiscent of office family portraits and certificates. Declarative and masculine, the subjects contained within these blocks are not paired with gaming devices but cans of Lynx deodorant. Gay as.

One photograph is by Will McBride: Mike in the “Shower,” Schule Schloss Salem, Germany. Although often used in the service of “sex education”, McBride’s photographs are homoerotic iconography on par with Tom of Finland (often found hidden away on lower bookshelves and restricted sections). Now the internet teems with blogs dedicated to the ceaseless cataloguing of vintage porn actors and beautiful pubescent boys from a bygone era. They are aesthetes’ commitment to the life force of beauty and undead eroticism. McBride’s photograph is of a “coming of age” nude boy in a communal shower, pouring water over his head with classic Flashdance connotations, mouth parted. Over this image, Rennick has superimposed a Lynx can, cinched in with a corset at the waist of the subject. The corset used in these collages is an early “electric corset” that emerged at the time that electronic beauty goods were marketed to women for the “medical” treatment of “hysteria”.

In a homoerotic context, Lynx represents lockerroom fantasies of gay adolescence with endless pornographic iterations. But as a “text” it is endlessly rich. Although Lynx was established in 1983, “The Lynx Effect” advertising campaigns whereby a man is suddenly irresistible to hordes of gorgeous hypnotised women really kicked off the 90s. When catching a whiff of the (in reality, putrid) scent of Lynx deodorant, women are seen to drop whatever they are doing, let their hair down, unbutton blouses and follow the man doused in the aerosol spray. Like zombies after blood in a trance-like state, the women are stripped of their personalities and everyday concerns, reduced to pure desire. While on the surface these women are objects of desirability, as zombies they are also devouring. They are thirsty and potentially dangerous (particularly in large numbers). Beware the femmes and gays.

If it weren’t clear enough already, Lynx cemented their penchant for apocalyptic scenes of (literal) biblical proportions in 2012 with their Lynx/Axe “The Final Edition” commercial. A man drives down abandoned streets, birds are migrating, furniture is on fire, a shattered globe lies in a puddle of water, a family hurriedly packs their car. He begins building a wooden structure that becomes an Ark for hot women who come in pairs, nose to the air as though endowed with a supernaturally enhanced sense of smell. The slogan was (variably) “Happy End of the World” or “Get it on for the end of the world”. In 2010 they also released an “Angels will fall” commercial where angels fall from the sky, forfeiting their heavenly status for mortal desires (a man wearing Lynx).

In the opening scenes of Possession Joan Crawford wanders the near-empty streets of Los Angeles, arms limp by her sides, saying nothing other than the word “David”. Beyond the clear zombie parallels to this opening scene (“David” might as well have been “braaains”), it is revealed while the woman is detained in a psychiatric facility, that she is Louise Howell, a woman who had become psychotically obsessed with a fuckboy named David. As is the case with Love Letters, our protagonist is cleared of any crimes she committed due to her “unsound” mental state. Diagnosed with schizophrenia, a doctor fittingly describes the progression of her affliction as: “the mind loses control and the body sinks into coma. Then, in the biblical sense, we might say that such a person is possessed of devils and it is the psychiatrist that must cast them out.”

Rennick mentioned that the scale of his Lynx Corset works were smaller than those of the women to reference the (largely animated) trend of “vore” porn—or swelling giantesses feasting on tiny men. And certainly the far-off stares of many of the women are menacing—particularly Promesse de Bonheur (Acuity), which features a glamour shot of Merle Oberon and Promesse de Bonheur (Wealth), which shows Claudette Colbert in Cleopatra (1934). What truly sets them apart, however, is that where the Lynx Corset works depict the full bodies of the male subjects, the female subjects of the Promesse de Bonheur works are decapitated, floating headshots like Warhol Monroes. When I pointed this out to Rennick, he sent me some SOPHIE lyrics that (mis)align the beauty psychosis of artifice, commerce and the face:

My face is the front of shop

My face is the real shop front

My shop is the face I front

I’m real when I shop my face

Sélection de Paresthésie Prestige is peppered with the rich history of chthonic femininity as it oozes out of mass cultural history. Rennick’s work is complex, layered and, truthfully, a psychosexual nightmare. Despite the soundtrack, the bright gallery lights bouncing off the white walls and reflective aluminium, produce an intensity that is closer to “torture lite” than relaxation. It is more akin to “White Room Torture”—the psychological torture technique that uses neon lights to obliterate any shadows or colour, inducing prisoner depersonalisation and causing hallucinations and psychotic breaks. It evokes the more menacing connotations of “pins and needles” and bodily dissociation. Rennick has transplanted the archetype of the insane, expressionless and insatiable woman beyond bygone Hollywood starlets into Lynx zombies and the neurological cocoon of technology. The devouring mother archetype dual-wields the womb and the web, she is the matriarch and the matrix. Like the zombie, she is pure unadulterated (monstrous) desire.

Audrey Schmidt is a writer and Melbourne Personality.