Van Gogh and the Seasons

Anthony White

There are many extraordinary works of art to be seen in Van Gogh and the Seasons and yet certain aspects of the National Gallery of Victoria exhibition are disappointing. Individual paintings that stand out as masterpieces of modern art are shown side by side with frankly insignificant and minor pieces. In addition, several of the works that visitors might reasonably have expected to encounter including those depicting sunflowers and the artist's self-portraits are—with one exception—not present. A far worse drawback, however, is the ill-conceived audio-visual presentation to which viewers are subjected before entering the exhibition space.

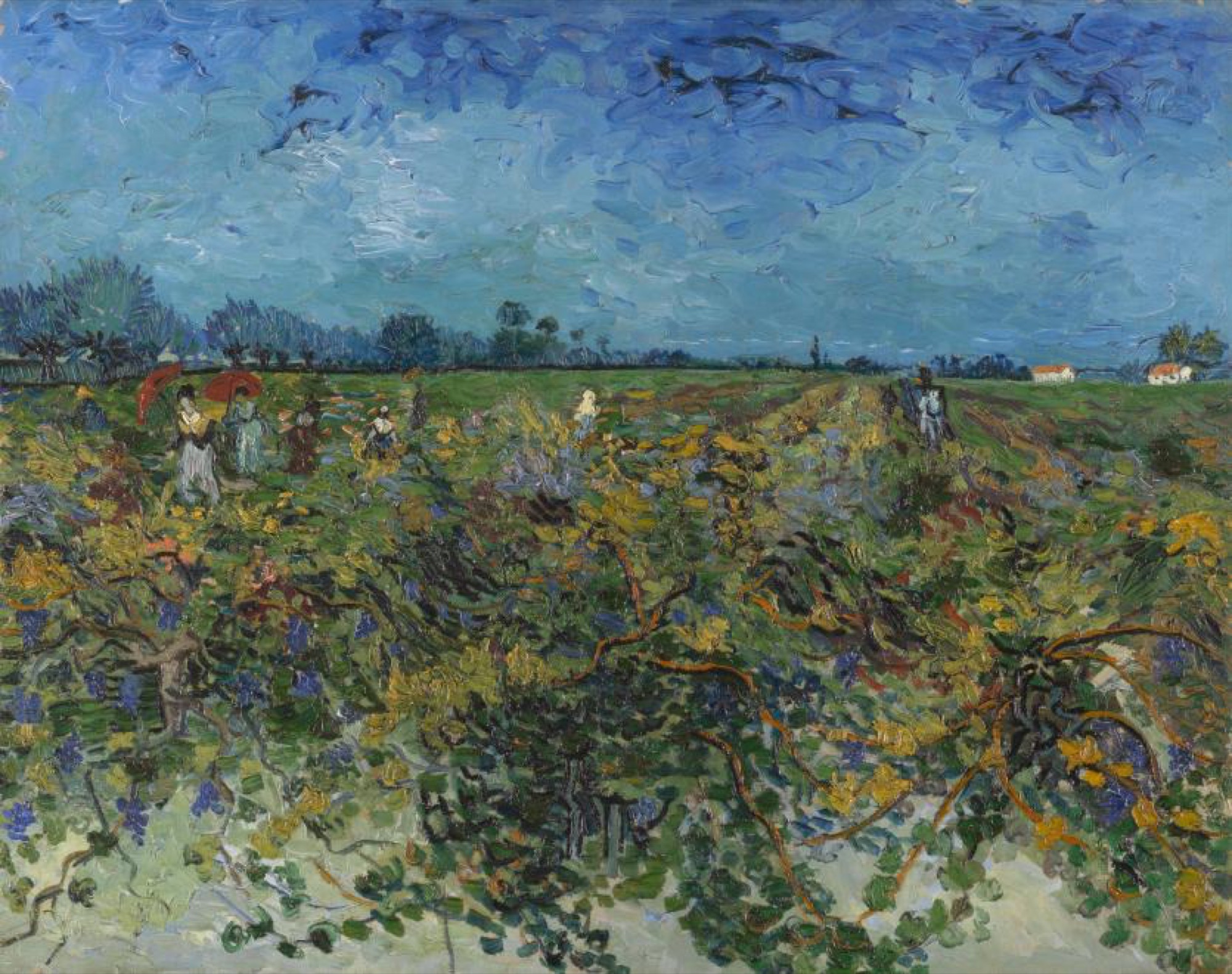

A work from October 1888 painted near Arles, one of the first works the viewer encounters in the exhibition proper, is titled The Green Vineyard. The palpable presence of the pigment applied by the artist in thick, stubby strokes to represent grapevines is the most prominent element of the composition. At the same time the lighter greyish areas near the bottom of the canvas suggest a world of empty space opening at the viewer's feet. By comparison the sky above the crisp horizon line in the distance has been solidified into a woolly mass composed of squiggles of intense blue paint. In such works, we witness the artist's continuing reliance upon 17th- century Dutch landscape paintings, his unique interpretation of French impressionism, and the daring compositional strategies he borrowed from 19th-century Japanese prints with their shocking collisions between near and far. The human figures—never the artist's strong suit—are almost lost in the dizzying morass of texture and the see-sawing effect of space created in the juxtapositions of sky, horizon, and foreground. Such figures remind us moreover that the artist, who never properly mastered the art of drawing, produced many pedestrian depictions of labourers of which there are far too many in the Melbourne exhibition. No doubt it is interesting to discover more about works for which the artist is relatively less famous, and thereby put his later, far more important paintings into context, but many of the early works are dull and uninspired.

Another work from December 1889 painted near Saint-Remy is titled Olive Grove with Two Olive Pickers. In response to his symbolist colleagues Paul Gauguin and Emile Bernard, who were painting biblical themes in their quest for a higher spiritual purpose for art, Van Gogh shows us a humdrum scene of olive pickers that nevertheless powerfully suggests the meeting of human and vegetable, high and low, solidity and emptiness. Angled strokes composing the sky reflect those describing the ground; violet patches of colour near the base of the canvas complement the yellowish strokes of colour visible in the sky above; and the gnarled branches of the trees mirror the labourers who reach up to collect their harvest. As the curators make clear in their intelligent labels and in a beautifully produced catalogue, in such works Van Gogh displayed his unique capacity to synthesise influences from a broad range of radical painting techniques while remaining rooted in traditional themes concerning the ideal harmony between humans and nature.

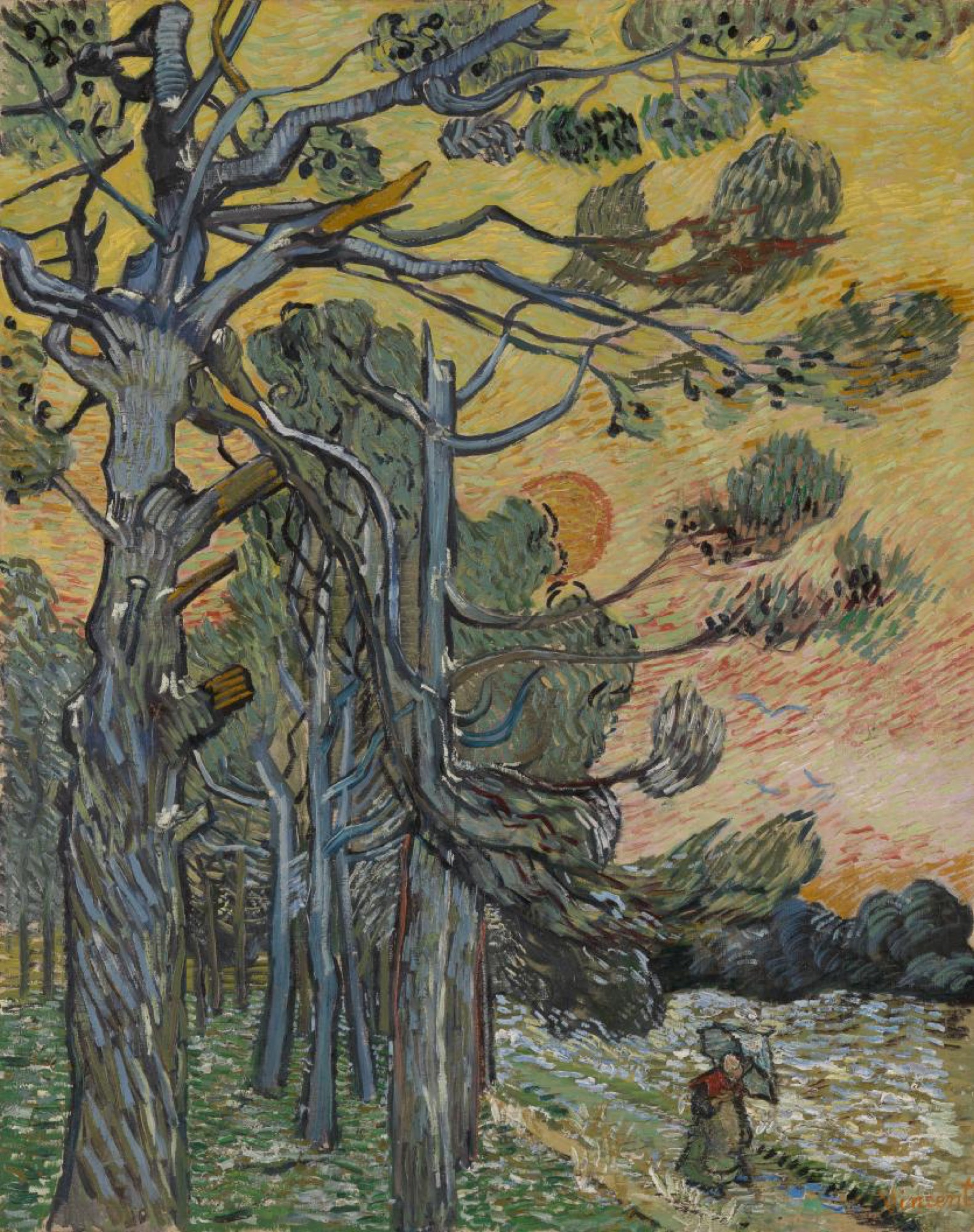

At this point in his career, however, Van Gogh's life was anything but harmonious and many of his compositions betray a dark aspect of his personality. He once described a tree in one of his paintings of the grounds of the asylum in Saint-Remy where he was voluntarily confined as “like a proud man brought low”. Similarly, in Pine Trees at Sunset of 1889 by distributing slashes of green tone over the sky above a scene of ravaged pine trees the artist sought to represent what “misfortune and sickness” can wreak on human beings. Rather than dwell on the artist's battle with mental illness, the curators have chosen to emphasise a different theme: the cycle of the seasons which repeats every year and continuously alters the visual appearance of the landscape that Van Gogh painted. The artist was preoccupied with the changing seasons for many reasons, including their visual properties and the impact on the everyday lives of rural labourers. Moreover, as Joan Greer points out in her excellent catalogue essay, Van Gogh's works belong to a tradition of artworks on the theme of vanity, which link the passing of time to the observable changes in nature and to religious understandings of human mortality. His frequent depictions of reapers working in the heat, for example, functioned both as a celebration of the intense light of summer and a reflection on how we are ultimately cut down in death.

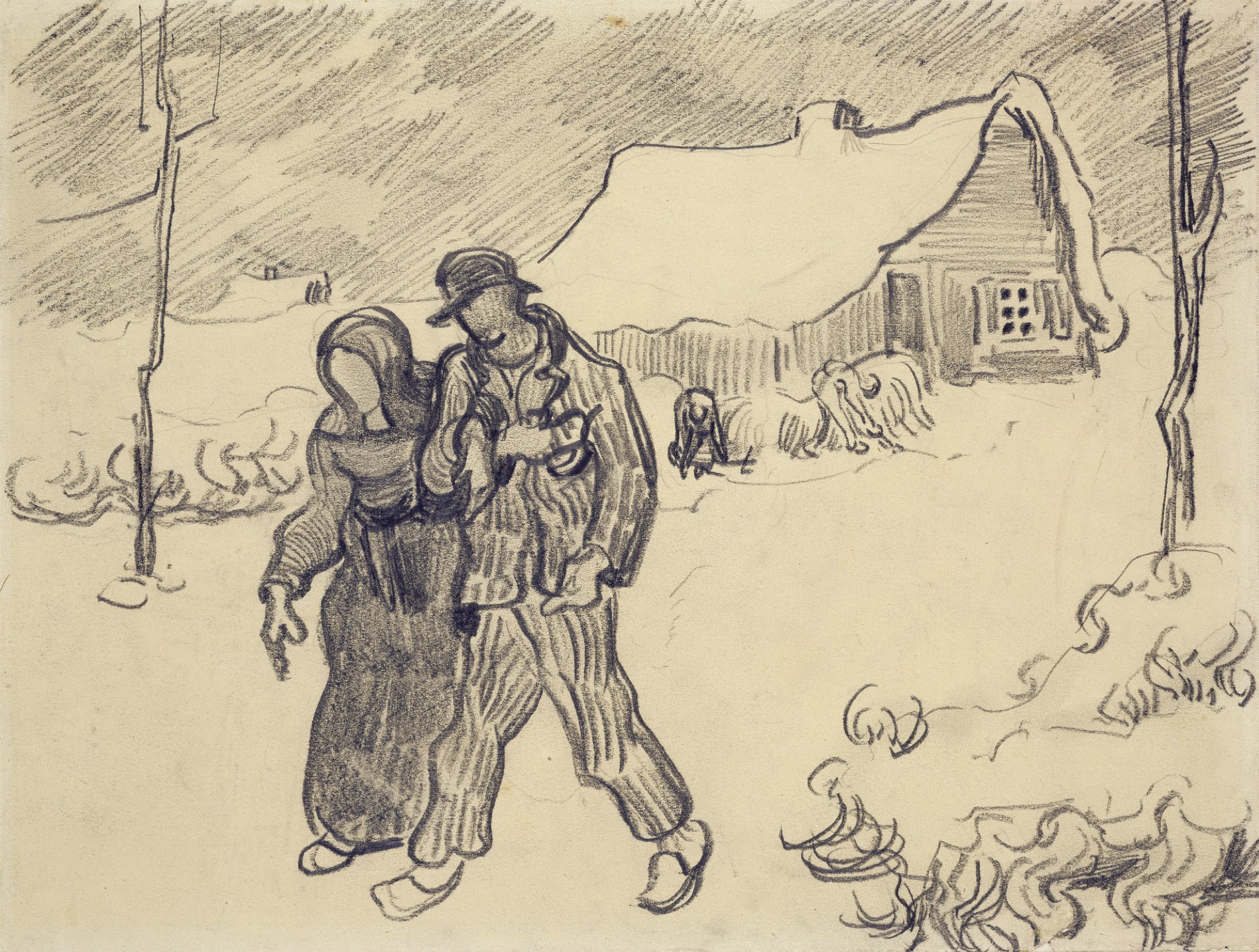

Given the clichés about the wild genius who suffered for his sanity the curators' impulse to downplay the role of the artist's health is perhaps understandable but misplaced. This is particularly the case given that the exhibition includes a rare example of a work produced by the artist during one of his most severe bouts of illness—the drawing Winter Landscape with Couple Walking of 1890. Like the others made at the that time, in this work the line becomes less assured and irregular, wobbling nervously around contours and indiscriminately filling space in a manner quite unusual for the artist. In such works, we see none of the distinctiveness with which, as can be observed in a work like A Wheat Field, with Cypresses of 1889, Van Gogh normally rendered each element of the landscape using a series of completely unique signs to materially distinguish it from the things neighbouring it. When Van Gogh was truly afflicted by mental illness, in other words, his work was strikingly different in character to the paintings for which he is now celebrated.

Among the many important canvases in the exhibition that depict the asylum is Tree Trunks in the Grass of April 1890. A relatively insignificant patch of the institution's garden featuring a carpet of grass is punctuated by dandelions and shows tree trunks running almost from top to bottom of the left side of the canvas. No doubt this work was in part aimed, as the catalogue entry points out, at creating a calming effect for the viewer. However, the astonishing quality of the jagged, geometric marks depicting the rugged bark of the trees suggests that the artist was so immersed in nature that he could view a tree trunk as a bizarre, almost unrecognisable object. In this sense, his understanding of nature bears comparison to that of Jean-Paul Sartre, who, as he describes in Nausea, felt he had encountered the very essence of existence in the form of a chestnut tree that was “this black, knotty mass, entirely beastly, which frightened me”. Like the way that the windblown clouds in A Wheat Field, with Cypresses look more solid than the mountains below them, Van Gogh was determined to make us look completely afresh at the world around us. The works that resulted from this ambition, as this exhibition shows, were not always pleasant and could be shocking or intensely disturbing.

The layout and design of the exhibition was for the most part very fitting to the nature of the work and its thematic focus. Of interest were the rooms showing the artist's own print collection and the ways in which Japanese art affected the artist's work. Different sections of the exhibition were elegantly separated by subtle layers of black gauze that allowed visual access while appropriately corralling viewers. I was also impressed by the illumination of the artworks, which was revealing without being showy. However, in the first room of the exhibition there was a monstrous array of flat screen televisions through which a symphony of light and sound was transmitted. Here the viewer was exposed to filmed, panoramic vistas of the countryside in the south of France accompanied by booming voice-overs that narrated Van Gogh's biography and read out his letters. While being confronted by this barrage of audio-visual sensation I wondered what motive could have made the gallery, by way of introducing the world's most passionate and talented apostle of the glory of the natural world, create a technological abomination on a scale heretofore unthinkable. Could the gallery be so challenged by the exceptional quality of Van Gogh's painting, by its capacity to outshine any attempt to curate “visitor experience”, that it designed an installation that would remain, for all the wrong reasons, the most memorable component of the exhibition?

Dr Anthony White is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. His most recent book, co-authored with Grace McQuilten, is titled Art as Enterprise: Economic and Social Engagement in Contemporary Art (IB Tauris, 2016).

Title image: Vincent van Gogh, Self-portrait, 1887 , oil on canvas, 44 x 35 cm © Musée d’Orsay)