Screwball

Verónica Tello

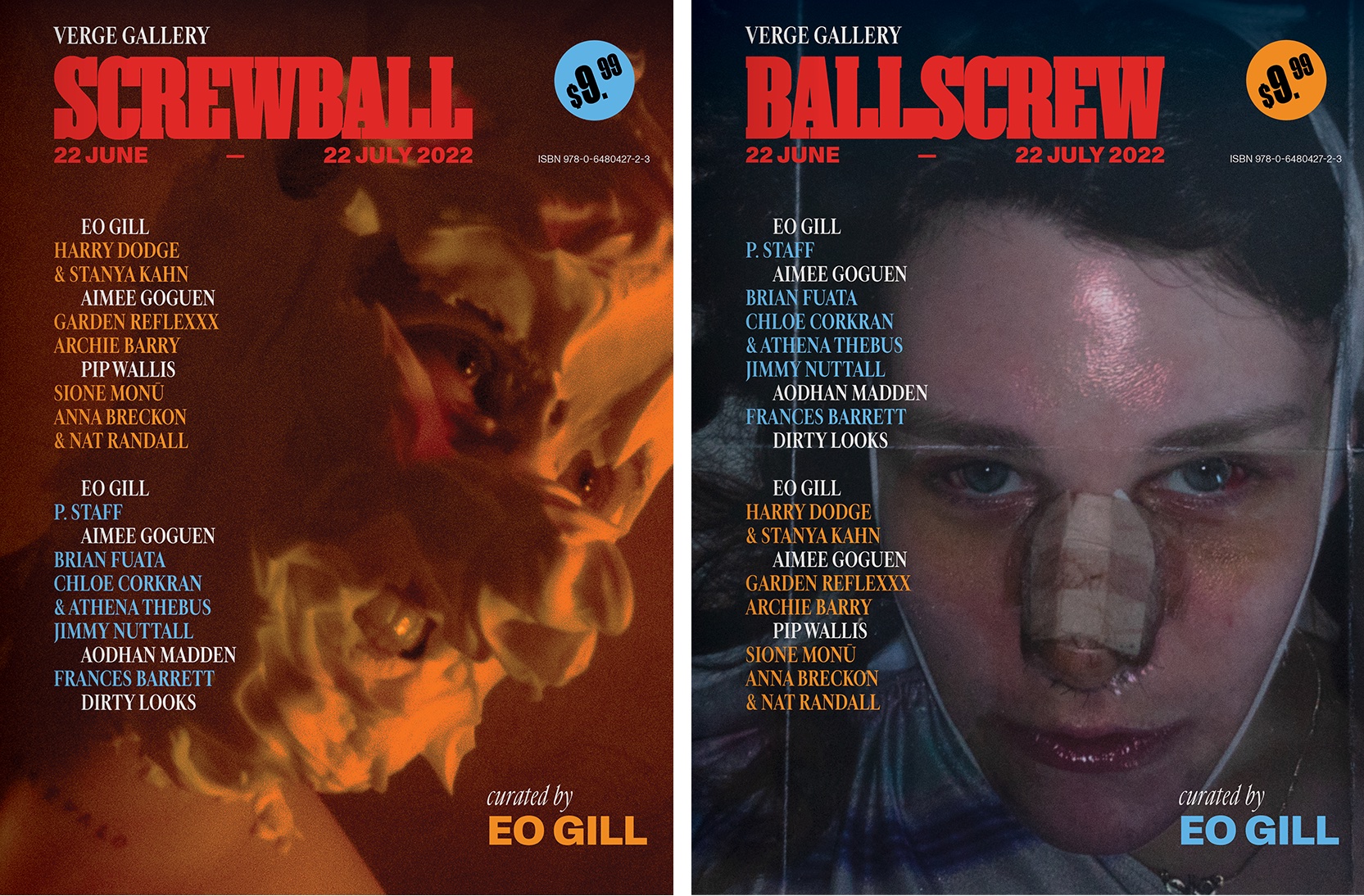

Screwball hesitates to show all its cards at once. Walking into Verge Gallery you’ll think it a small show, comprising of two works on paper and a few screens of video. The gallery’s façade, usually transparent glass, is plastered in what look like old 1980s porn magazine covers (in fact, they are covers for the exhibition catalogue designed by Ella Sutherland), that obscure and protect the exhibition within. A timber bench—the kind you’d see in a locker room—is positioned opposite the show’s main screen, to entice you to sit down and get to know the show. Screwball may take its time but will, in turn, reward you with the pleasures of edging.

Screwball, curated by Sydney-based video artist EO Gill, strategically and powerfully responds to the current hyper-visibility of gender and sexuality discourse in Australian art institutions. Know My Name and Queer are the two most obvious examples, but there’s others like the research group Kink or Rex Butler’s recent enthusiasm for “queering” the likes of Sidney Nolan. You could say that such hyper-visibility emerges out of the desire for relevance and futurity. Indeed, the futurity of Australian art institutions seems to be contingent on structural change—diversifying, decolonising, queering. Identities are moulded into verbs as institutions heed the demands of contemporaneity, differentiating themselves from the normative paradigms of yesteryear. It’s in this context that Screwball emerges, hedging its bets on the politics of evasion, disappearing and “not cumming”.

The curator EO Gill is also an artist whose practice mines film culture—Hollywood, pornography, amateur videos—re-enacting scenes, appropriating scripts and messing with genres, often with Gill as protagonist and/or with their queer community in haul. Works such as Physical (2018) and CLEAVE (2021)—which feature performances by Screwball artists Chloe Corkran, Athena Thebus and Nat Randall—reveal Gill’s pleasure in laying bare the perversity of cis-hetero spaces (the Australian suburban home) and film culture (including highly gendered roles such as the “bad” mother in CLEAVE). Across their practice, Gill’s aesthetic is intentionally amateur: handheld cameras, non-professional actors, bad lighting, awkward makeup and off-kilter editing are strategically deployed to withhold cinematic immersion and make their audiences sit in discomfort. Gill’s artistic practice, while not under review here as it was not on show, is the invisible foundation for Screwball.

The exhibition’s title refers to screwball, the Hollywood rom-com subgenre known for screwing with straight culture. Emerging in the United States during the 1930s and 1940s (my personal favourites are George Cukor’s The Women of 1939 and Preston Sturges’ The Lady Eve of 1941), screwball films tested the limits of marriage, monogamy and the couple, not by showing sex on screen (you know, censorship), but rather through witty dialogue and camp aesthetics which undermined heteronormativity. Screwball, at least as a genre, is not in any way re-presented in Screwball. Instead, for Gill, screwball is a vital historical framework. It’s a citation and a precedent of how film can screw. It’s a method.

And for Gill, to screw means to refuse linear plots, coherent dialogue or language, character development—any of the things that make the mainstream film experience satisfactory and provide closure or climax. As Gill notes in their catalogue essay “Ballscrew”, their interest in slow, banal scenes that refuse easy gratification is exemplified in the porn video Patient Cums During Physical Exam (free on Pornhub!). A doctor examines a patient, asking if there’s any “pain or discomfort” while checking the patient’s heartbeat, pressing their abdomen and tweaking their nipples. The humdrum content is as important as the tedious temporality: Patient Cums During Physical Exam uses remarkably long shots, unusual in mainstream porn, to cultivate the pleasures of edging.

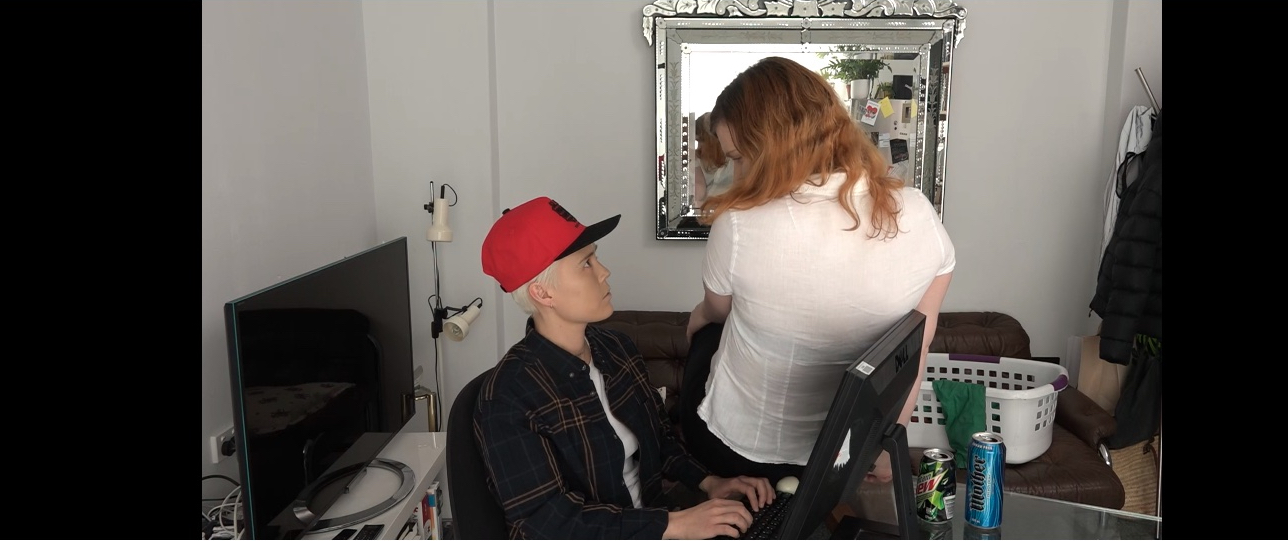

Many of the works in Screwball are lucid illustrations of Gill’s philosophy of anti-climactic art, not just refusing linear-narrative pleasure, the filmic equivalent of jizzing, but embracing languor too. I’m thinking of the loosely stitched vignettes of a group of friends having chit-chat and then getting wasted in Jimmy Nuttall’s Fabulina (2019), or the banal and intimate conversations between two friends on a road trip in Garden Reflexxx’s Blue Car (2022), or the stilted scenes of leiti sovereignty staged across mundane suburban landscapes in Sione Monū’s Only Yesterday (2020). And I’m also thinking of Anna Breckon and Nat Randall’s Piece of Work (2022), which meditates on the nuances of workplace procrastination, micromanagement and people-pleasing as activities of erotic sadism which linger yet ultimately go nowhere (repeating, looping).

For Gill, a key node in the genealogy for the Screwball aesthetic is Harry Dodge and Stanya Kahn’s iconic film Can’t Swallow It, Can’t Spit it Out (2006). In the film Kahn is dressed in a green and white polka dot dress, fake blonde braids and a Viking hat. She wanders aimlessly around LA going on rambling tangents with a soft toy in the shape of a Swiss cheese wedge in hand. Meanwhile Dodge, always behind the camera, follows her as both a voyeur and occasional subject of Kahn’s heckling. The film’s charm is its purposelessness—it goes nowhere.

To my mind, Kahn and Dodge’s film is included in Screwball not only for its content (which is easily and perhaps more comfortably viewed online), but because it acts as a home for the remaining works in the show. Or to use a concept from Heather Love, it acts as a “shelter” which allows us to stay with queer history and the many negative, and traumatic, feelings it contains.

To return to Can’t Swallow It, Can’t Spit it Out is to open up an archive of queer, and in particular trans, experiences. As Gill notes in their second catalogue essay, Can’t Swallow It, Can’t Spit it Out generates a trans reading of the 1957 Walt Disney animation What’s Opera, Doc? where Elma J Fudd plays a Viking who hunts Bugs Bunny. To flee Fudd’s phallic spear, Bugs uses drag—donning two blonde braids and a Viking hat—to successfully seduce Fudd. However, while in an embrace Bugs’s hat and wig fall off, outing them and sending Fudd into a rage of violence for being deceived, resulting in Bugs’ murder. While as Gill notes, just as Bugs is a transfeminine character, Fudd could also be transmasculine (citing his small stature and service-bottom vibes), What’s up, Doc? and Can’t Swallow It, Can’t Spit it Out cite the violent affects of the queer/trans film archive especially in relation to visibility/being outed. After all, in Can’t Swallow It, Can’t Spit it Out Kahn re-enacts the Bugs character with a bloody nose, as if to continue where What’s up, Doc? ends. In a show that is otherwise mostly Gill’s friends and local community, the inclusion of Kahn and Dodge allows Gill to establish a broader queer art history for screwball aesthetics, while also foregrounding the visibility of queerness (and its dangers).

Gill’s exploration of the social violence that mark queer archives, post Dodge and Kahn, expands into other aspects of the show, namely by exploring the body as archive and site of resistance. I read Gill’s inclusion of P.Staff’s Pure Means (2022) as a way of naming the body as archive of negative feelings. The video centres on the choreography of LA-based dancer and performer Gregory Barnett, who we witness in a state of flight, despair and self-harm amongst the threatening sounds of fireworks and bullets, with heart-racing heavy metal playing as the soundtrack. Returning to the violence of the 1980s/1990s during the AIDs crisis, Screwball’s catalogue, designed by Ella Sutherland, references the aesthetics of the California-based gay porn producers Palm Drive Video and Drummer Magazine, which experimented with non-penetrative sex, leather, S&M and kink as forms of activism (the catalogue design builds on Sutherland’s work Glyph of 2020, which responded to the 1980s/1990s Australian lesbian erotica magazine Wicked Women).

Gill also told me that Screwball has been deeply informed by Dirty Looks, a Los Angeles/New York based curatorial collective initiated by Bradford Nordeen. One can easily imagine how Dirty Looks’s curation of, for example, porn videos from the 1970s/1980s—including, say, films from one the first lesbian porn studios, Fatale Media, or the deeply homoerotic Tattoo (1975)—could offer an art historical home for Screwball’s love of realcore (amateur, authentic), symbolic and non-genital forms of eroticism. Such films beckon historical communities to linger.

If Screwball seeks to coax into being histories and communities bound by sex, art and activism, it’s not the only recent work to do so. One of the highlights of Melbourne’s Rising festival this year was Randall and Breckon’s performance work Set Piece (2022), for which Gill was lead camera operator. The work critiques millennial lesbian culture for its ahistoricism and bourgeois aspirations—wanting to live in a Darlinghurst or Potts Point apartment (which is where I live!)—-and the insistent banal conversations about the quality and price of Aldi cheese or Harris Farm groceries (which I might participate in sometimes). As one of the millennial characters pursues an elder woman, Set Piece grapples with how sex, however “inclusive” gay marriage/homonormativity may be, is always indelibly marked by queer histories. Legal and political forces still determine the limits and potentialities of queer futures.

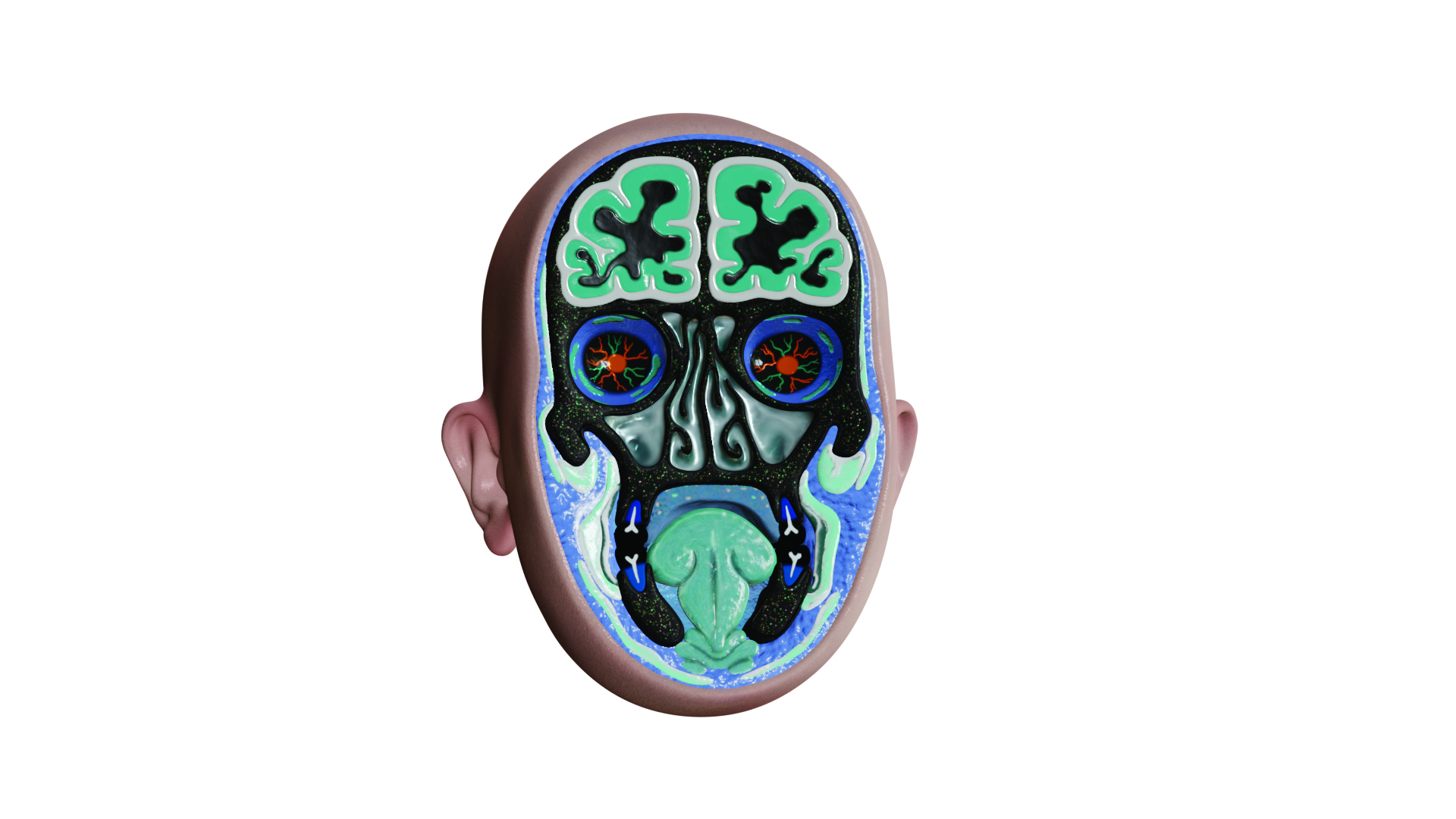

As queer bodies are summoned and instrumentalised for both visions of progress (à la Queer) or depravity (à la the church via Australia’s 2022 Religious Discrimination Bill), the strategy of negation—that is, the refusal to appear or to appear on the terms set by others—reveals its power in Screwball. Archie Barry’s video Scaffolding (Preface) of 2021 calls into question the human as a stable concept—a Western construct grounded in hetero/cis epistemologies—and experiments with the body, face and voice as sites for reconfiguring the self so as to evade being “clocked” and “tagged”.

For their wallpaper/poster work In Dramatic Roles Such as These (2022, used on Sutherland’s covers) Chloe Corkran and Athena Thebus develop and enact the personas of Comedy and Tragedy. We see Comedy (played by Thebus) from a worm’s eye view, their face covered in whipped cream and menacingly standing over Tragedy (Corkran), who peers up at us, bandaged and bruised (recovering from cosmetic surgery). In spite of the seemingly abject horror of the scene, here negating oneself via fiction becomes an essential method for self-determining the conditions upon one can appear and radically mutate.

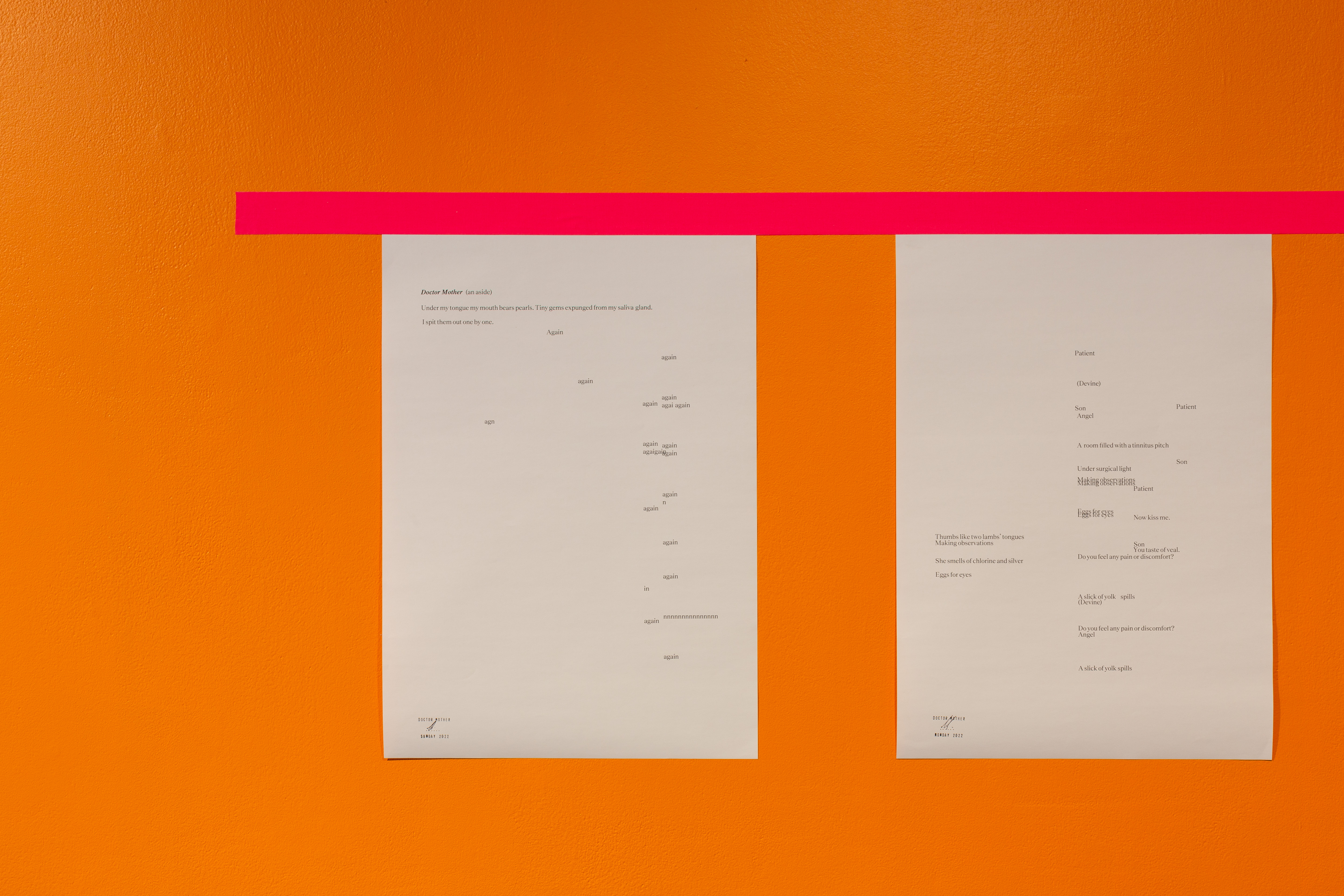

Fiction as negation is also at play in Frances Barrett’s poster work The Verses of Doctor Mother (2022), which along with In Dramatic Roles Such as These represents the only other non-video work in Screwball. In The Verses of Doctor Mother Barrett develops a script for her fictional character, Doctor-Mother, which she first conceived while writing erotic fan fiction in response to Gill’s CLEAVE in 2021. “Son. You taste of Veal”, writes Barrett, joyfully performing the highly charged, sexual and power dynamics of Doctor-Mother and the subservient, delicious Patient-Son.

In their respective works, Barry, Corkran, Thebus and Barrett embody queer negativity by performing “bad” citizens, humans, partners and parents. The stakes of such a strategy are revealed in stark ontological terms in Negativity (2022), Brian Fuata’s contribution to Screwball. Here Fuata speaks to non-human and human experiences of “being stripped bare” by external forces. “Aaargh, I’m naked”, we hear Fuata say, as the work grapples with the experience of being put on show and Othered on the one hand (say, by heteronormative institutions), and how on the other, the practice of edging—almost cumming (like an apparition)—is a radical act of self-negation (edging as negation).

As shows such as Queer or Know My Name demonstrate, the construction of identity and sexuality is always taking place in the visual sphere. Thus, however satisfying it might feel, to bring certain identities to light is not in itself politically progressive. Gill’s show challenges Queer and Know My Name by presenting not “queer” or “gender” identity, but rather the very conditions in which identity is produced. This is, as Barrett notes in her catalogue text for Meatus (2022), queer not as image but as method.

NGV and Rex Butler seem to be driven by a desire to find an image of queerness to revitalise Australian art history. Gill, the artists in Screwball, as well as Meatus and Sidney McMahon’s Maggott (2022) refuse to show this image. They refuse, in part, because they know the dangers of queer visibility.

Earlier this year the former Arts Minister, Paul Fletcher, singled out Gill in The Telegraph and The Daily Mail over Australia Council funding for Screwball, ridiculing and exploiting the show for political gain. Fletcher exposes the risks of a show like Queer, despite its best intentions. As Juan Dávila, an artist included in Queer, reminds us, such a risk is not new. His 1984 work, Sexuality and Politics, made during the AIDs crisis, states: “We are being made spectacles of” (and it’s worth noting that Dávila hesitantly agreed for his art to be put on display for Queer). As the dangers of hyper-visibility continue today, Gill’s astute tactic is to refrain and conceal. Behind a wall of porn-magazine covers, which transform Verge into an illicit space, however temporary, Gill has created a shelter for their screwy community to cum—or not—together.

Verónica Tello is Senior Lecturer, Contemporary Art History and Theory, UNSW Art & Design, Sydney.