Ruth Maddison, It was the best of times, it was the worst of times

Chelsea Hopper

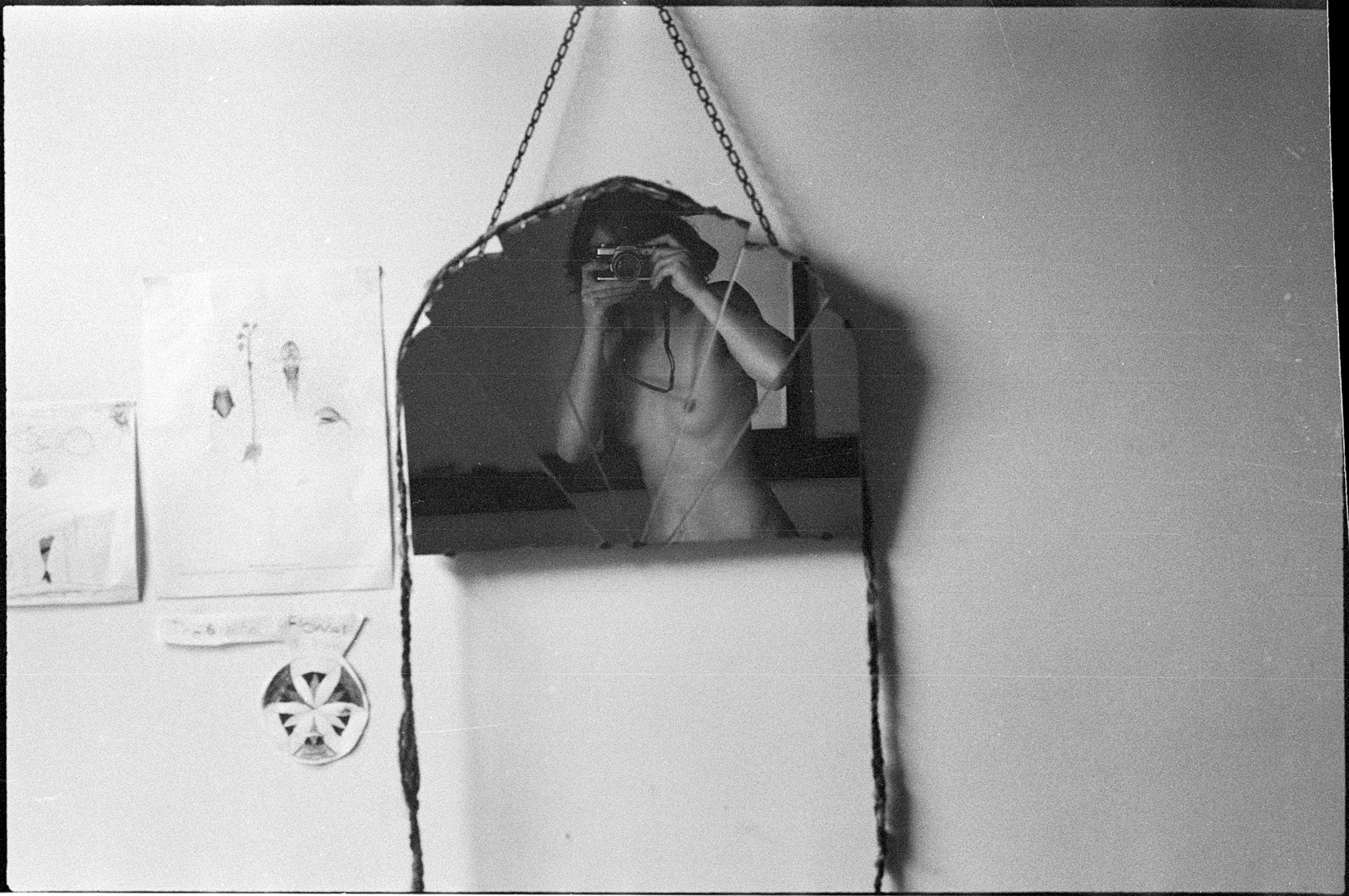

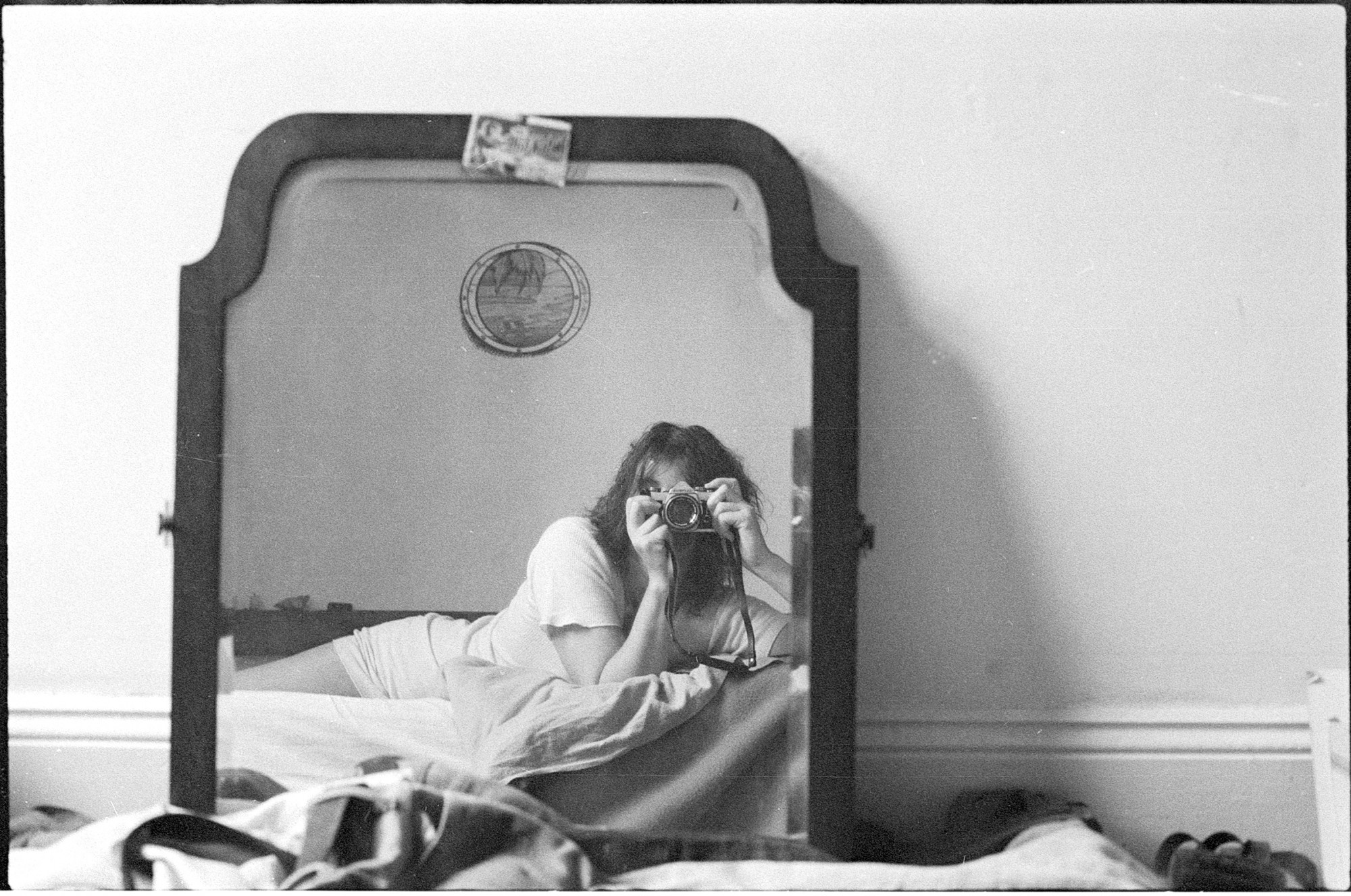

Ruth Maddison began taking photographs at the same age as I am as I write this review. She was thirty-one. Her housemate Greig Pickhaver lent her a 35mm camera while living in a share house on Rathdowne Street in Carlton North. We see the results of this transaction in First roll of film (1976), a series of candid self-portraits pinned at the entrance of her exhibition, It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, currently on display in Fitzroy at the Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP).

This major survey exhibition accounts for over forty years of Maddison’s photographic practice, which she began after the long days of her twenties working as a builder’s labourer. Ruth resists both the romantic narratives of a photographer – one who was introduced to it at an early age – and the arc of creativity that is often associated with age, namely that one’s best work is made when one is young. This exhibition, I would argue, illustrates just how versatile and transitional Maddison’s style, subject matter and interests are, making it difficult to pinpoint exactly what her “best” work is and at what stage of her long-withstanding photographic practice this occurred.

There is a vast amount of work (over 520, mostly prints) on display. To make sense of the many photographic series Maddison produced from 1976 to 2020, each wall of the gallery, bar the final room dedicated to a newly commissioned work, is chronologically divided into large clusters of framed and unframed prints. Chunky excerpts from essays in the exhibition’s catalogue sit next to these collections along with helpful details that cite the number and various series of prints within each cluster. Maddison’s exhibition was conceived pre-Covid, along with a number of staffing changes at CCP, so there isn’t a curatorial attempt (via wall labels) to categorise Maddison’s practice in overarching thematic terms, which are often so imposing, distracting and painful to read past the first sentence. Instead, there is insight, and it is welcome.

From 1976 are Maddison’s early self-portraits—at times she’s unclad, but always peering into a mirror, face hidden. They offer a rare glimpse of her physical presence within the camera frame. The focus quickly flips, quite literally in the same roll of film, introducing us to her three children, joyfully playing or being playful with their mother who is now also an avowed photographer. Curiously, sitting in the vitrine opposite the series, an overexposed black and white silver gelatin print of one of Maddison’s children, Sarah, shows her lying on the floor donning what appears to be a wig—coloured bright yellow.

Sharing the vitrine are the earliest examples of Ruth’s hand-colouring in a collection of prints from the series Miss Universe (1979). These snaps, taken of a televised beauty competition, end up filled in with Texta felt-tip pens of colours blue, yellow, pink and green. I can’t help but imagine Ruth sharing this process with her children. “Colouring-in” is a fundamental part of one’s early childhood. And Textas are a cheap, non-toxic and economical way to make marks with a limited range of colours. Self-taught, perhaps this process was a way for Ruth to find her own kind of agency over the automatic photographic image. Coloured-in, the images are personalised and forsake the finer technicalities associated with developing and printing black-and-white photographs.

The hand-colouring technique takes place in a softer palette in the series Christmas Holidays with Bob’s Family, Mermaid Beach, Queensland (1977-78), hung on the opposing wall bookending the gallery’s entrance. By using coloured and grease pencils and felt-tipped pens in each of the thirty prints, Ruth literally highlights particular objects contained within her camera’s frame. Bob, whom we see just once in a mirror reflection from the series, First roll of film (1976), was Ruth’s partner at the time. In this series, Bob’s family and his relatives are captured during the summer holiday on the Gold Coast in 1977 indulging in a glut of typical Anglo-Australian Christmas shenanigans: donning paper crowns lifted from crackers, sunbaking, beer sipping, unwrapping presents, shirtless napping, playing sport in a grassy backyard and gathering by the beach with cool drinks close by — the first of many series taken by Ruth with a social documentary bent.

There is something about this series that I can’t quite put my finger on. During my gallery visit, as I stood near a group of women, I couldn’t help but overhear them utter, “God, how did she do it?”, and watch on more than one occasion visitors’ failed attempts to leave the gallery, getting physically stuck in stopping and looking at this series. They repeatedly re-examine the images and then go to the trouble to ask at the person at the front desk exactly how Ruth “did it”.

This reaction contrasts from the experience for Ruth and her peers (think of Micky Allan, Janina Green, Sue Ford) in the 1970s when first experimenting with hand-colouring prints. At the time it wasn’t thought of as a particularly subversive technique. But it nevertheless provoked deep disdain. To give you an idea, in a review by photographer Max Dupain of a series of large hand-coloured photographic prints by the late Miriam Stannage, he called the addition of colour “an emotional seducer like the tasty chemical additive of one’s favourite jam”. As photography continued to push its way into the art discourse (remember, it wasn’t until 1976 that there was a solo show dedicated to colour photography at a museum, ever!), the small group of female photographers from this generation were negotiating this technology and establishing themselves as a community of sharing. They employed both their autonomy and the photographic medium to bring about a new liberating approach.

Next to the Bob’s Family series, a neat cluster of images—an assortment of pinned silver gelatin prints, some archival, others printed in 2020—depict women’s labour. Here, “labour” takes on many forms: being a single mother, working in a hospital, as a packer at a chip factory, twisting wires for Telecom, selling cured meats, learning how to weld at TAFE, and even dancing. Taken from a number of photographic series throughout the 1970s and 80s, these women appear warm, friendly and dedicated identities. A favourite is a pair of prison guards who miraculously appear both kind and authoritative despite their symbolism.

One of the photographic projects funded by the Art & Working Life program titled And so… We joined the Union (1985) documents union members at their place of work. As Helen Ennis notes in her catalogue essay, Ruth occupies “a viewing position that is equalised”. Her democratic approach to image-making deflects an approach that patronises or glamourises these working women. Maybe this is also why the snaps of their leisure time, dancing at the Vehicle Builders Workers Ball, reinforces that there is more to work than just working.

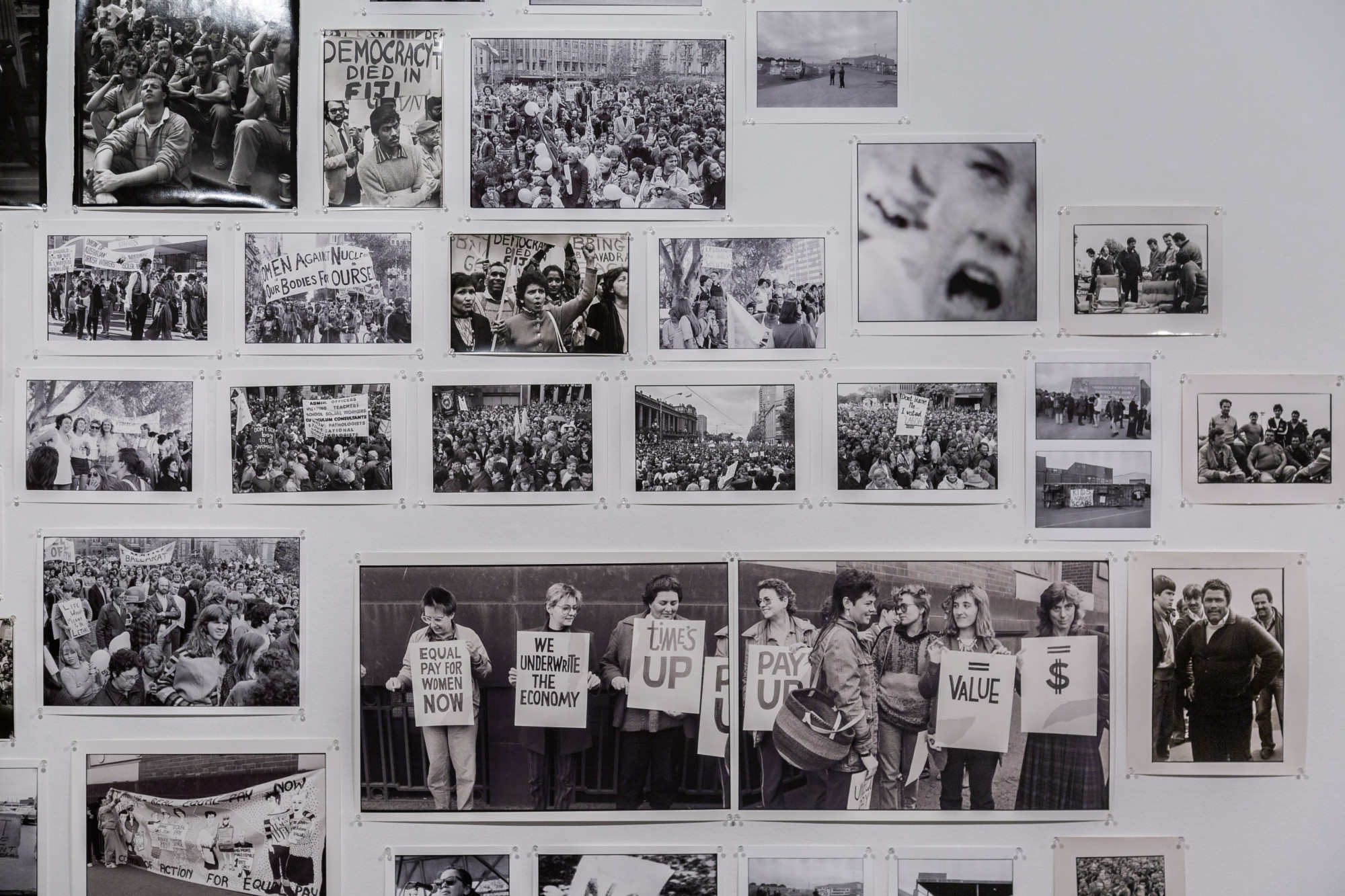

Ruth’s politics are reflected in the creative feminist communities she documented. It is most evident in one of the largest clusters of framed and unframed portraits of the many artists, friends, performers, writers, photographers who have crossed paths with her camera over the past four decades. In a series next to these portraits, Ruth documents rallies, protests and picket lines from the 1970s to late 1980s in a series of black-and-white prints. We see in them groups of women holding hand-painted signs: “EQUAL PAY FOR WOMEN NOW”; “LESBIANISM: THE ONLY SOLUTION”. This collectivism gets flattened by the individualising slogan that “the personal is political”, which is found on one wall label to suggest private personal interiority rather than the public political action documented in these photographs.

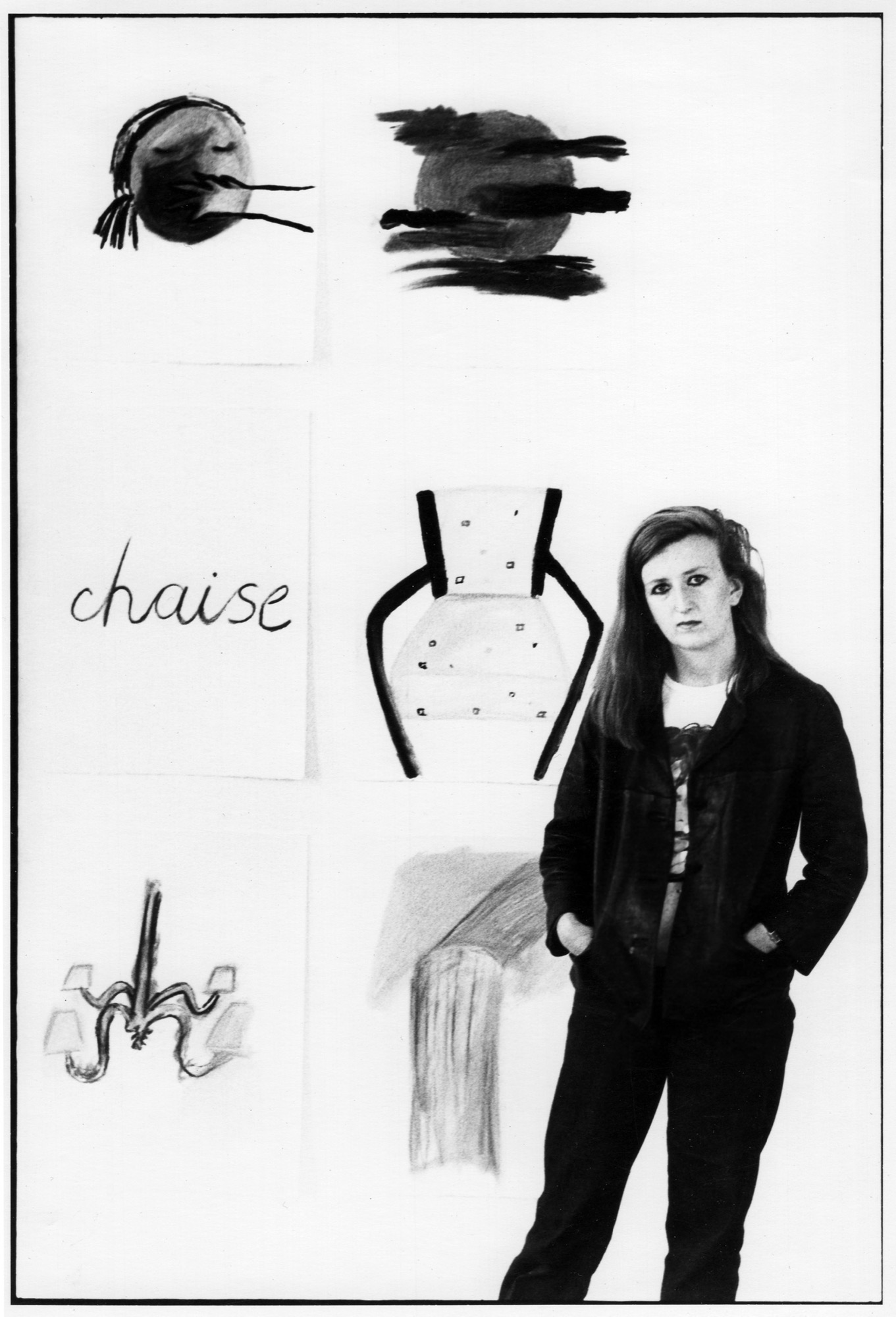

A sizeable collection of portraits from 1976 to 2017 point to Ruth’s ongoing dedication to her long-lasting friendships and inadvertent documentation of the community surrounding her. Some of the most striking faces of the Melbourne photographic community elbow each other within this scrambled mix of prints. A photograph of a fresh-faced Tracey Moffatt in her twenties, wearing a form-fitting bustier and high-waisted briefs, shows her caught in a moment preparing to shoot her now iconic series, Something More (1989). In another, a youthful Ponch Hawkes stands mid-conversation with novelist Helen Garner as her daughter Alice, pigtailed, waits patiently in a doorway. Garner appears again, this time in a large, framed hand-coloured print, standing on one leg holding a teacup. There’s a portrait from the mid-1980s of artist Micky Allan, a pioneer of hand-coloured photography, looking relaxed, smiling, as she sits in her Paris studio. A framed print of Sue Ford hanging out on a couch with her son Ben from the mid-90s rests next a portrait from the early 2000s of Anne Ferran sitting with her daughter, Claire. Smaller black-and-white portraits from the 80s of a melancholic looking Judy Annear and Jenny Watson decked in all black are honourable mentions, as examples of how Ruth manages to capture her subjects’ characters so well. I could go on, but I’ll leave the task of clocking the faces you recognise for when you visit—which you must.

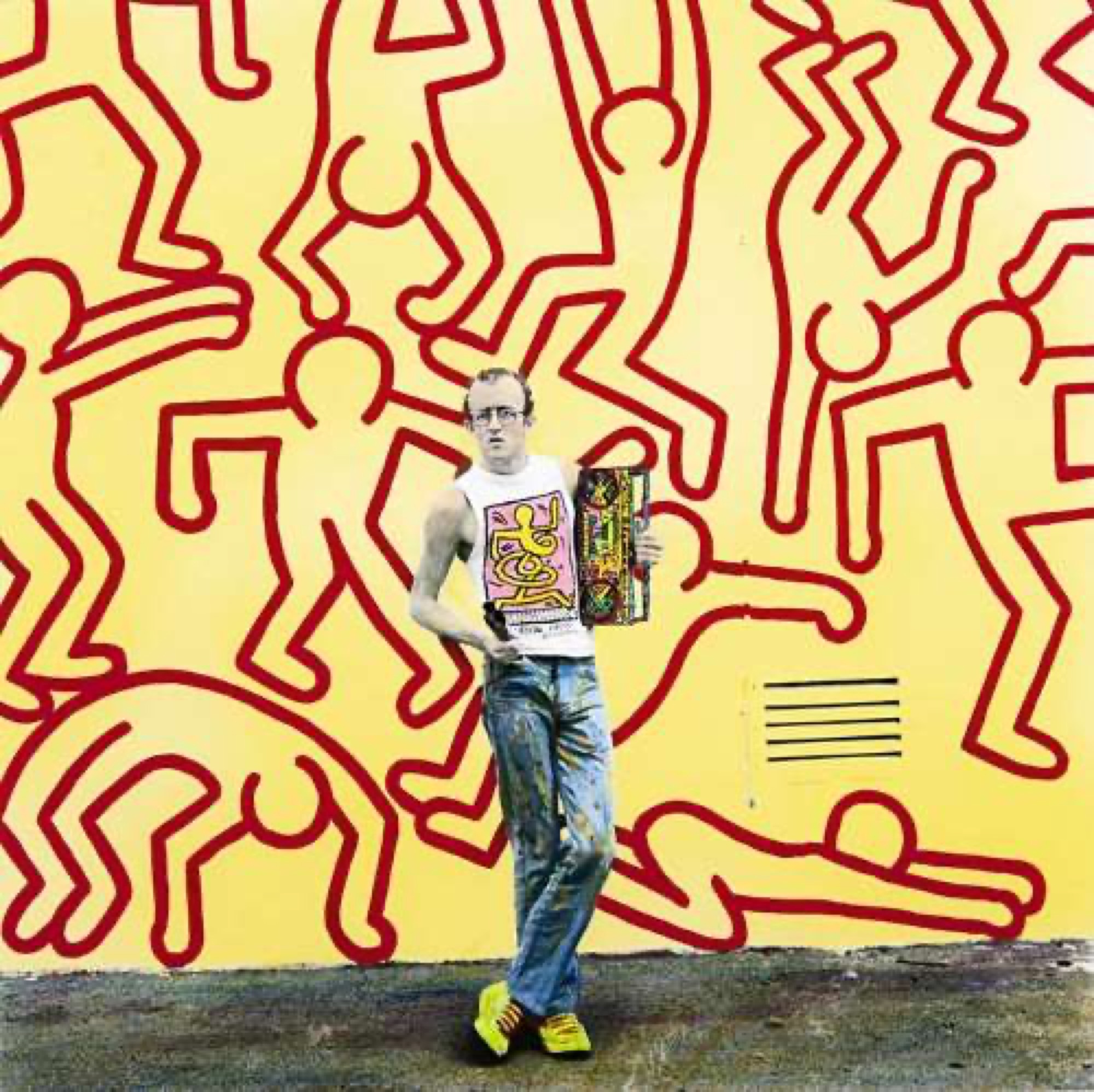

The generous mixing of dates in the collection of portraits counteracts the tendency to historicise and glamorise a period when everyone appeared to look young and cool. Although it’s quick and easy to identify the art stars, once you find them, they are absent from our immediate eye-line. Sitting at the tippy top of the cluster is a portrait of Keith Haring standing in front of his large mural, which is currently being restored down the road from the gallery in Collingwood. The pigmented print emits the very energy his iconic figures take as they jump around on the walls behind him. Hung at the bottom of the collection, a snapshot of Werner Herzog seen outside a cinema standing with filmmaker Paul Cox is only noticeable if you crane your neck or crouch down.

Maddison’s work also illustrates how the experience of a photograph can be shaped by the type of technology used. The black-and-white prints, especially from the 1970s and 1980s, unconsciously provoke a nostalgic idealisation or an inner desire to live or relive such times. The exhibition’s title also instils this mindset. This is not to say that Ruth’s photographs are outdated or that nostalgia in this instance is dangerous or a trap. After all, we’re not living in the nineteenth century when nostalgia (as I recently heard Adam Curtis say) was considered a psychiatric disorder. It comes with the territory of the medium, in particular, social documentary photography.

Around the corner, there is a series of landscapes taken at Monaro, a highway stretching across the eastern part of regional New South Wales that connects up to Eden, a small coastal town where Ruth currently resides. The series, titled There is a time (2009), acts as a visual break (or respite?) from the hundreds of faces displayed in the first half of the exhibition. These photographs remind me of when the American photographer Catherine Opie, best known as a portraitist, made a departure in the early 1990s to photograph freeways in Southern California. The physical shift in place also sees Ruth’s style adapt to her subject matter.

“I entered the community through photography”, Ruth tells me over email, referring to her relocation from St Kilda to Eden in 1996. Eden is a small working-class town known for its fishing and timber industries. The last large cluster of prints, taken in Eden and of their residents, once again generates a kind of non-hierarchical way of seeing: we are encouraged to dip in and out of these images, travel back and forth along the walls and pick where our eyes want to eventually rest. The colour photographs of young fisherman are especially curious in capturing the rough and raw working conditions along with revealing the sheer mass of catchments when farming the sea. In one image, a young man with thick matted dreads is shown sorting seventy boxes of squid; in another, a man wearing thick red rubber gloves stands on a mountain of caught orange roughy; on another wall, two young boys stand over a bloodied table, gutting fish. Ruth also interviewed the fisherman, and many of their stories about their working lives are placed next to their portraits, one of many social histories that reflect back to us her community.

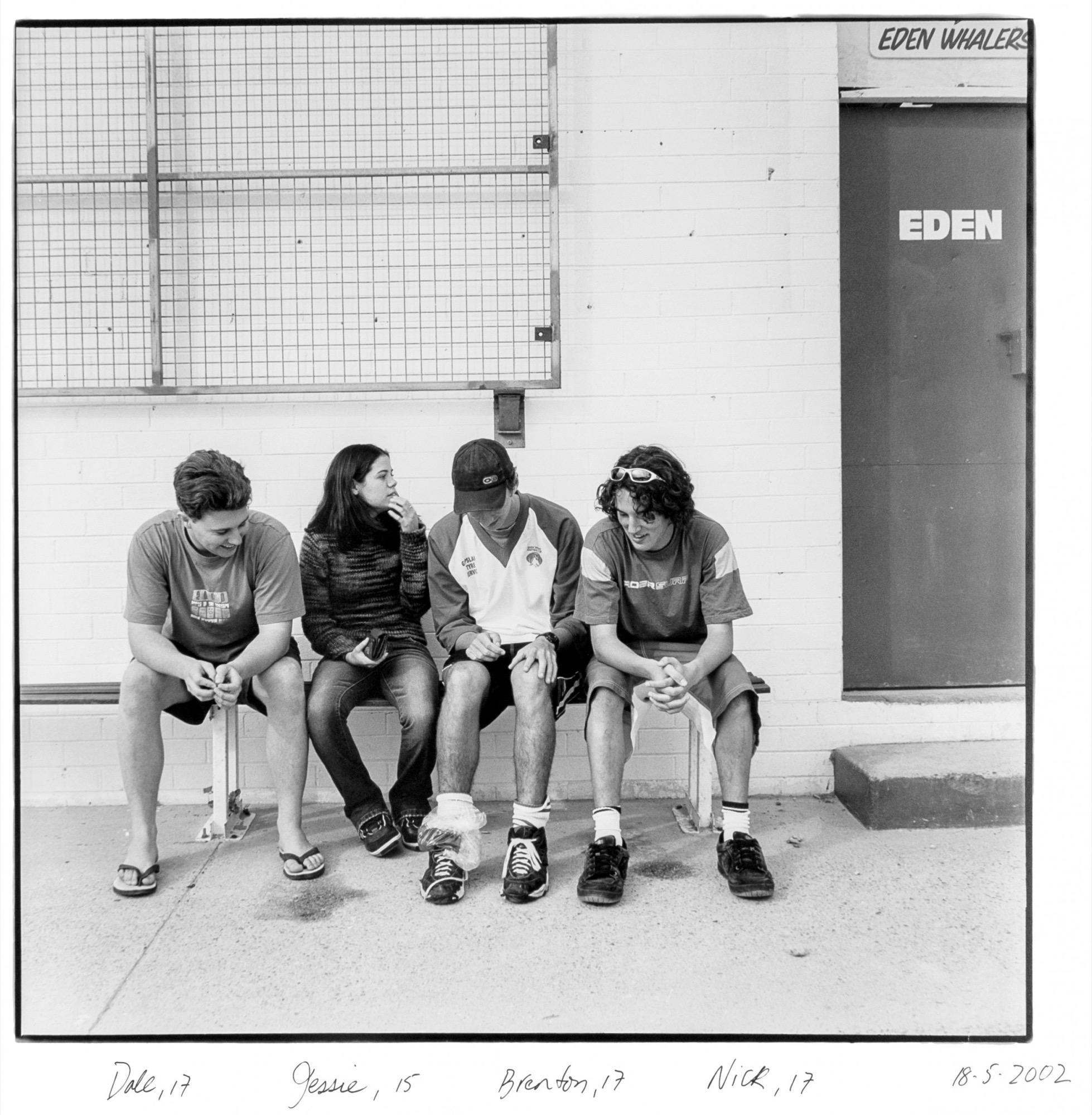

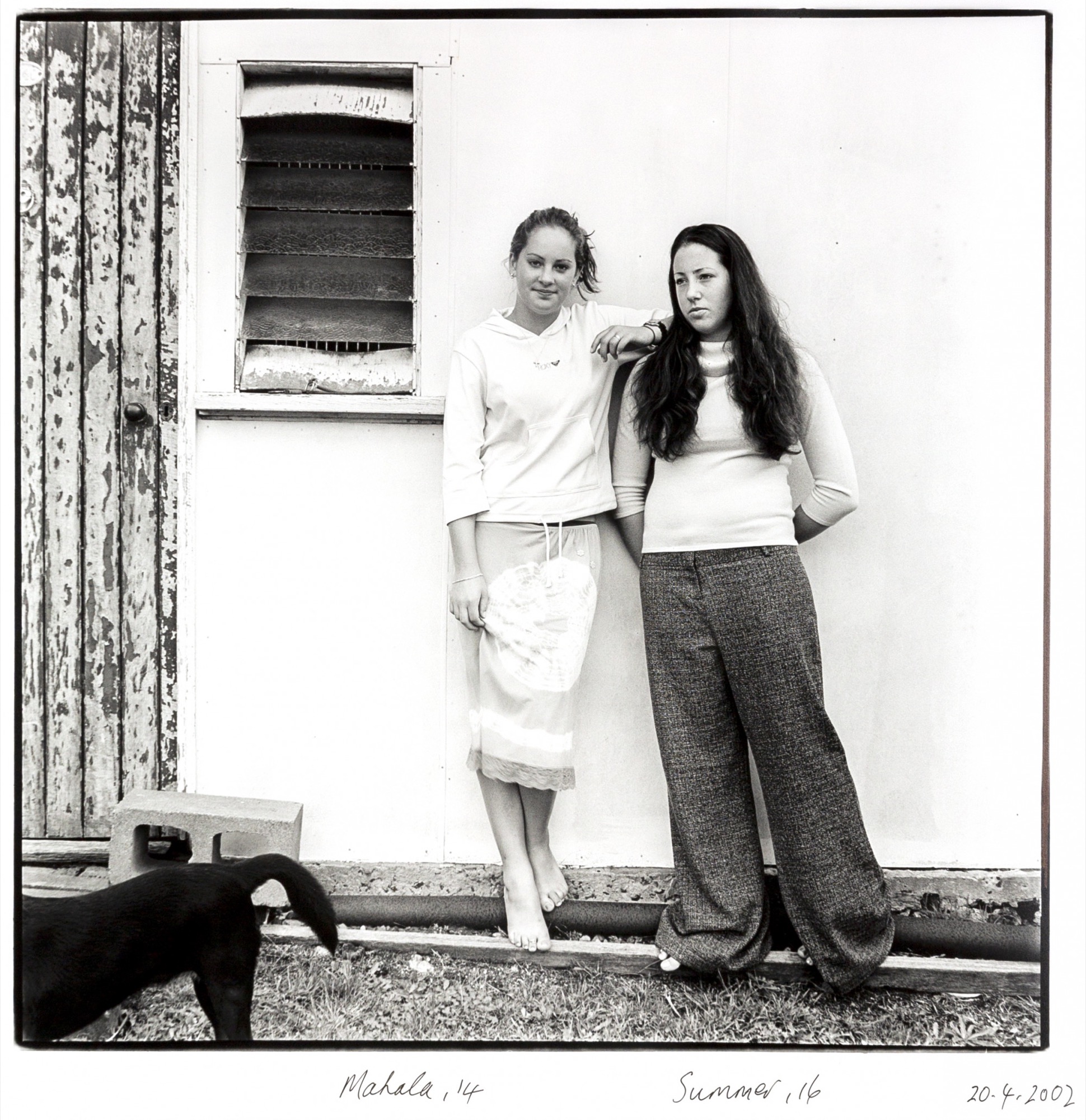

The social pressures to stay in a small town like Eden is felt in the portraits of teens from the series, Now a river went out of Eden (2002). It’s hard not to look beyond the early 2000s fashion they wear: cargo shorts, low-rise pants and one-shoulder crop tops. But Ruth’s portraits manage to capture this group of young people who are so financially vulnerable and insecure in these moments of indecision or ambivalence; where milling about outside a supermarket, hanging out with friends in a bedroom or on a couch are far more worthwhile activities than planning one’s own immediate future.

The most recent prints, scattered amongst the Eden cluster, document the devastation for many New South Wales and Victorian communities of the intense bushfires from the December 2019–2020 summer. Ruth, like thousands of residents along the east coast of New South Wales, was indefinitely displaced. We bear witness to evacuees lining up for breakfast at a sports oval and the unlucky reality of residential homes and properties completely decimated by the fires flooded in the skylines of an orange-yellow haze.

In December 2019, no one could travel from Melbourne to Eden due to the bushfires. A few months later, the town was thrown into a global pandemic. And it was not until the end of 2020 that Ruth finally found herself back in Melbourne. The CCP became both a workspace and studio before this exhibition finally opened at the end of February. As I reach the final room of the exhibition, I get the sense Ruth spent many hours in this space. It is not often we get to see so much of a photographer’s work and life, all at once, and so it’s no surprise that after such a tumultuous period like 2020 Ruth has dedicated such a large part of her exhibition to producing a substantial body of new work. The Fellow Traveller (2020) looks back into archive of Ruth’s own father, Sam Goldbloom, who since the Second World War was a political activist, working on the Jewish Council to Combat Fascism and Anti-Semitism.

The wall connecting this large space to the rest of the exhibition is wallpapered with reproductions of his political and peace movement posters along with blown-up versions also hanging up in the space. As Ruth’s father was on the World Peace Council from the mid-1950s to 1980s, a lot of travel to anti-war conferences were made to Soviet Russia, China and Cuba. An abundance of archival material, footage and hand-coloured photographs reconcile and reimagine Ruth’s father and his past. A selection of photographic prints is blown up, hand-coloured and framed, often editorialised and commented on by Ruth, either as a form of speculation or through her imagination in order to recollect or even reconcile her father’s life. Are memories reliable or can we only know what we choose to remember? Is the past what we think it is?

Before I visited the exhibition, almost all my peers who already had been told me that there’s too much work, as if it was a real threshold for them and they weren’t prepared for it. Is this not a broader symptom of looking at art today? We unconsciously power through rooms, scan the walls, get a general sense of what things are and walk out. Ruth doesn’t let you do that. There is so much and it requires our full attention. It requires a kind of meditation or “self-emptying” that frees you from the limitations of your perspective. The exhibition helps us see others and the world more clearly. And we owe it all to Ruth.

Chelsea Hopper is a curator and writer based in Narrm. She is also an editor at Memo Review and Index Journal.