Roots

June Miskell

“Where are you growing your roots? Who are you intertwined with?” writes adrienne maree brown. I’m reminded of these questions when I visit Roots, a group exhibition currently showing at the artist-run initiative Pari in Parramatta (Dharug land). Organised by Pari co-directors Brenton Alexander Smith and Amy Toma, and former director Talitha Hanna, Roots brings together a suite of works by artists who “contemplate ritual and reclamation as a way of grounding oneself and connecting with lineage and identity”.

Pari is no traditional white cube. A café that became an artist-run initiative in mid-2019, the bones of its former life remain: kitchen counters, sinks and tiles remain visible, and its walls are still decorated with menu-boards and strips of wallpaper showing what looks like a Santorini coastline. Indeed, since its opening Pari has placed a strong emphasis on its ties to the local community, marking its kinship with other spaces in Western Sydney like I.C.E., Parramatta Artists’s Studios and Granville Centre Art Gallery. One of Pari’s aims is to reflect “the social, the political and the deeply personal” via a “program (that) draws out ideas that are particular to our location in Western Sydney on unceded Darug land, and that resonate well beyond the local”. The current exhibition reflects this mission, introducing artists with roots within and beyond the local community.

This emphasis positions Roots within a broader (re)turn in “Australian art” to questions of cultural, regional and trans-national identity—-the 10^th^ Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art and the 23^rd^ Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, being large-scale recent examples of this. What distinguishes the Pari exhibition is its particular focus on ritual, as the practice that allows roots to come into existence and persist. “Ritual” might typically be defined as a religious or spiritual ceremony consisting of a series of actions performed according to a prescribed order. However, within the context of this exhibition, the essence of ritual is found in the act of repetition, and of using the body to give form to matter.

Upon entering the gallery, the first work I move toward is Monica Rani Rudhar’s sculptural installation Daughter of the Same House (2021). Adorned on individual hooks in rows of three are twelve almost identical pairs of glazed terracotta earrings coated with gold lustre. These pieces replicate (on a larger scale) a pair of hand-made earrings gifted to Rudhar as a baby by her Bhua (aunty), and which Rudhar recently temporarily misplaced. The earrings, Rudhar states, “connect me to what feels like a distant heritage and far-away family”. Rudhar’s exaggerated re-rendering of the earrings reifies this connection, transforming a private memory into a public work that cannot be (again) misplaced or lost.

Hanging adjacent on the same wall and also pursuing a method of ritual-as-recreation is Trawlwoolway artist Edwina Green’s (Untitled) Kelp Bag, 7 (2019—). Part of an ongoing body of work that speaks to intergenerational disconnection and its impacts on familial ties, Green’s workpays homage to the history of Lutruwita (Tasmanian) practices by recreating a carrier bag used to hold and carry water. In contrast to the serialism of Rudhar’s earrings, Green’s work comprises a single bulbous and leather-like receptacle, made with harvested nerocystis leutkeana (bull kelp) lined with natural fibre twine-threaded seams. Yet both Green and Rudhar gesture towards the tactile, form-giving nature of ritual. For Green, this is demonstrated through the use of kelp which grows in saltwater, while for Rudhar this is shown through the use of terracotta (literally translating to “baked” or “cooked” earth). These processes see ritual as a practice that maintains and tends to one’s roots.

If Green and Rudhar’s exploration of ritual foregrounds tactile processes and organic materials, NC Qin’s Flow: River of Knives (2021) turns to the industrial and the inorganic. For Qin, who is probably best known for her glasswork, this work is the first that explores a medium other than glass. Across six hammered and rusted steel panels, Flow: River of Knives shows a burnt metamorphic landscape that is reminiscent of traditional shan shui paintings which typically depict mountains, rivers and waterfalls. Fused to the surface of the panels with neodymium magnets is a wave of carved glass knives that cascade in a downwards left to right motion. Thousands of chiseled indentations and dimples that contour this landscape index the strenuous bodily and repetitive process that Qin endured creating the work.

To view Maissa Alameddine’s dual-channel video installation Act I: Burden (2021-22) I sit on one of the five black foldable stools, carefully noting the floor label that requests visitors to avoid sitting or standing on the rug. As melodic fragmentations of Arabic folk songs sound through the speakers below, I watch Alameddine pensively pull, pick and discard leaves from an abundant Lebanese vine tree (areeshi) that envelops an entire wall and which extends onto the rug-clad ground. The overgrown nature of the tree, Alameddine states, signifies its neglect during the pandemic when domestic rituals of gathering and cooking for each other were difficult to do. The absence of ritual is further marked in the moments where Alameddine’s body blends into surrounding foliage or when she disappears entirely. In the exhibition room sheet Alameddine asks: “Why do I have an Aereeshi in my garden?” This question prompts me to ask myself: “Why do I have a kalamansi tree growing in mine?” Such questioning points toward the complexities that the transference of familiar yet non-native plants carries for diasporic settler-colonists of colour grappling with our disconnection from our ancestral homelands to now growing our roots on stolen land. In Act I: Burden Alameddine ruminates on missed togetherness and a disruption of ritual practices, and further invites us to consider the complexities of how we connect to our roots through the transference of such rituals.

Connecting to ancestral homelands is a central theme in Roots. Talia Smith’s work It’s OK, you don’t need to (2019-22) is a collection of six digital photographic prints taken over a three-year period that explore her connection to and physical disconnection from her ancestral homelands of the Cook Islands. Floating and overlapping one another, the photographs feature archival and landscape imagery from the Cook Islands and the backyard of the country Smith now calls home. There is, however, a third spatio-temporal location present that is distinct from the rest of the photographs due to their black and white tone and still-life staging. Situated in between the others, Smith engages the Sāmoan notion of the vā. In ‘Tatauing the Post-Colonial Body’ (1996), Pacific author Albert Wendt writes that the vā “is the space between, the betweenness…that holds separate entities and things together”. This sense of betweenness is foregrounded by Smith as these photographs capture yet collapse the various distinct times and locations that they span. Here, Smith weaves together a personal narrative of the vā that reaches beyond this distance.

Perhaps the most deep-rooted of the works in the exhibition is the single-channel video work Korrobi Ancestral Spirit (Women) (2020). This work is by the community-based Indigenous dance company Jannawi (which means ‘with you, with me’ in Dharug language), and was recorded on Dharug land at Shaw’s Creek Aboriginal Place that rests along the Nepean River in Yarramundi—-only a forty-five-minute drive west from Pari in Parramatta. In the video, members of Jannawi perform the creation story of Kurrobori, which they animate through ritualised movement. The camera pans from a circular clearing across intertwined starry and earthly landscapes, connecting sky, ground, water and women. This transcendental image, however, is interrupted by scenes taken by an aerial drone. As traces of surveillance—-and thus, violence—-these expansive bird’s-eye views of Shaw’s Creek Aboriginal Place point to the colonial violence inflicted on Aboriginal camps there during the Frontier Wars (as described in this recent inquiry). Settler-colonial violence continues to be deployed through what Aileen Moreton-Robinson terms “white possession”—-the racial logic of land and property ownership that continues to disrupt the exercise of Indigenous territorial sovereignty. While gesturing towards this logic, the drone’s vision also appears to be reclaimed by Jannawi, laying out the landscape surrounding Shaw’s Creek as an important meeting, fishing and camping place.

There are two particularly powerful scenes in Korrobi Ancestral Spirit (Women). The first closes in on three of the women’s hands as they begin to sculpt and mold mounds of soil. The second turns to their feet as they repeatedly press, step and kick into the ground. Perhaps what Jannawi shows us in the connection of hands/feet and ground is the ritualised connection of the body to Country. Within the context of the exhibition, this stands as a contrast to Rudhar and Green’s works, which show us the finished objects of such rituals. Jannawi shows us the embodied rhythms and movements that connects one to identity and cultural practice.

For the organisers of the exhibition—-Smith, Toma and Hannah—- “roots provide a staunch foundation allowing one to weather the storm”. I pause to sit and reflect on the following questions: What are the storms that we inherit and find ourselves in? How might the works brought together in Roots reveal something about how one protects and sustains oneself and one’s communities despite these storms? The final two works in the exhibition by Nadia Refaei and Mika Benesh provide some answers to these questions.

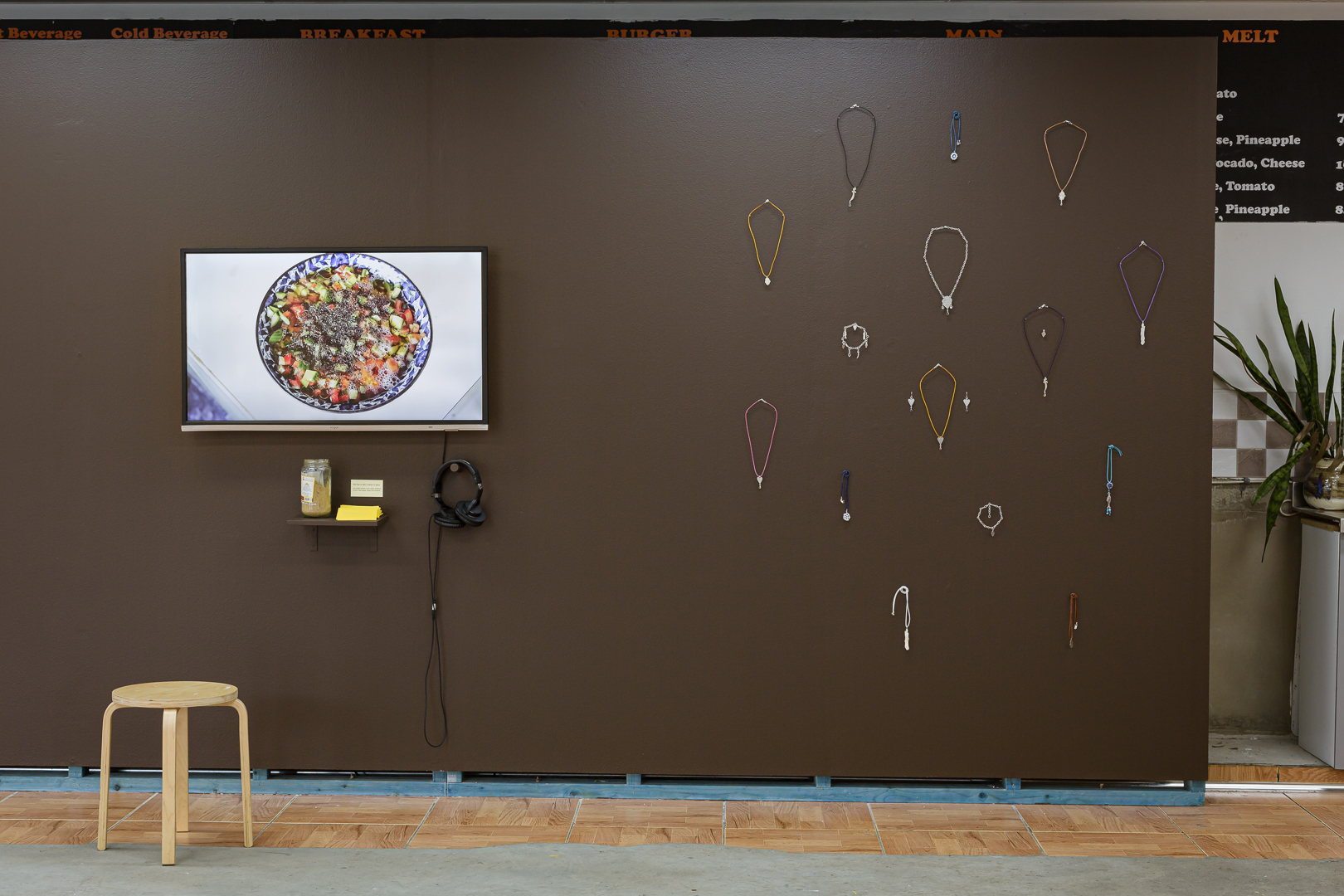

Make Kabsah with Me (2020) by Nadia Refaei is a single-channel video displayed in tandem with a shelf that holds an open jar and small yellow envelopes containing spices for audience members to take home with them. The video follows a conversation between Refaei and her father as they prepare Kabsah, a traditional dish of the Arabian Peninsula. Woven throughout this part documentation/part instructional cooking video is an oral history of familial migration from Saudi Arabia to Tasmania. In this work, Refaei explores the sustenance that food offers both as a daily ritual and as a means to pass on intergenerational knowledges and memories.

Amulets (2022) by Mika Benesh is a collection of wearable sterling silver amulets made from a variety of cut gems, gently hung in a row along the wall. Carvings in the silver mark stories “passed down through families, between friends and lovers in exile” which attest to the liveness of Jewish cultural practices. Benesh calls upon amuletic styles found in Jewish Iraq, Iran and Kurdistan, yet inscribes them anew with “new family mythologies, queer blessings and homoerotic medieval Judeo-Arabic poetry”. As adornments that signify safekeeping and protection in one’s travels for the wearer, Benesh’s amulets emanate a generosity that feels expansive while remaining tangible. It also recalls root’s homophone “routes”, suggesting that no matter how far one may travel there will always be a way back within and in relation to one another. Here, in these final two works by Benesh and Refaei, a gift of sustenance or a talisman for safekeeping for us to take away from the exhibition—-literally and metaphorically—-is offered in a shared ritual.

Before I leave Roots, I leaf through the pages of Pari’s newly launched publication Cool River City that sits on a countertop. The publication is a “community handbook for a changing climate” which shares practical climate resilience tools and tips shared by local artists, elders, healers, architects, scientists, wild gardeners and bush regenerators. As in Roots, Pari proposes ritual as a practice which nourishes and supports the roots we inherit and are intertwined with.

Indeed, the works in Roots are joined by a shared reverence for inherited ancestral, cultural and historical knowledge. On the one hand, the exhibition reckons with the complexities that otherwise come with being uprooted from such ties and locations by practices of colonisation. On the other hand, it locates ritual practice as a means of nourishing the self as we move in, against and through the world. What Roots and adrienne maree brown invite us to contemplate is not just the root-causes of the storms we may inherit and continue to move through but rather the vigour of surviving rituals that allow us weather such storms together.

June Miskell is a writer and editor based on Gadigal and Wangal land. She teaches at UNSW Art & Design.