Roger Kemp: A selection of etchings from the estate

Victoria Perin

It has been said that Roger Kemp would not have been able to make the etchings currently on display at Charles Nodrum Gallery “without the timely establishment of George Baldessin’s print workshop at his studio in Melbourne”. This review is less about an online exhibition where Kemp’s achievements are presented in high-resolution images, and more about peer-to-peer service, or “collaboration”, in the Melbourne art community.

The Winfield Building (now demolished, although the façade remains) stood between Collins Street and Flinders Lane. The first-floor space was originally used by artist John Neeson, who rented it as a studio but was also living there illegally on-and-off. It was tough city-living, with the floor below used as a chicken coop for “500-1,000 chooks”, for sale to nearby restaurants during weekends. In late 1968, when Neeson could no longer afford the rent ($10 a week), his teacher and mentor Baldessin offered to take it over. Baldessin was in his early thirties, and he had developed a system of paying his students from RMIT to assist with his prints on weekends. This informal apprenticeship sprouted a coterie of youthful followers, with Neeson acting as head studio assistant. Neeson retained his workspace and worked in place of paying rent, while Baldessin got the extra hands he needed to make his art.

Etching is a process artform requiring an intimidating sequence of copper, bitumen, acid and heavy machinery. To simplify the process, it’s necessary to have an experienced printmaker around to help. Barring some very rare exceptions, printmaking in Melbourne was handed down in this peer-to-peer format. Around the world, particularly from the late-1950s on, commercial services developed that would help artists make and sell fine art prints. Despite there being a sustained enthusiasm for printmaking in Melbourne in the same period, few professionals arose to take on sustained facilitating roles. In Melbourne, instead, we got Baldessin and his atelier, which he transformed from a derelict squat.

Baldessin’s Winfield Building studio became a new site of artistic ambition. Tate Adams, Baldessin’s own former teacher and mentor, had a gallery in Crossley Street that exclusively marketed prints. Baldessin encouraged local artists to make work in his personal studio, and Adams could then exhibit it. In 1973, they formalised this arrangement into a business when they opened a commercial print workshop called the Crossley Workshop on the floor below the studio (displacing, I imagine, the chooks). Kemp walked into Baldessin’s workspace in 1972 as a respected elder artist, and through their collaboration he made dozens of intense abstract etchings that have variously been called some of the “greatest” and “most magnificent” of Australian art history.

Kemp had won the hotly contested Blake Prize for Religious Art in 1968 and 1970, alongside a string of other prizes that saw the introverted artist quickly “come in from the cold” of critical neglect. Kemp was a mystic. Obsessive about his own artistic project, he showed to those who knew him very little interest in the work of other artists (and much more interest, conversely, with classical musicians). Transcriptions of his interviews show that Kemp was in the habit of talking about all of his artmaking at once, meaning he was rarely able to talk about any of it, specifically.

His language was hyper-personal, all-consuming. “Most people would never listen to Roger”, recalled artist Jan Senbergs, “He would get in there and start giving off his theories and everybody would sort of go glazey-eyed and wonder what the hell he was talking about”. In one excerpt from his interview with the artist/critic James Gleeson, Kemp talks about how his own ideas overwhelmed him:

Energy, you know. Itʼs a matter of energy. The ideas are there. Theyʼve got hundreds of them, but I canʼt, you know, write. One day probably I could produce a dozen really good major ideas ready for major works. Come face up to them, you know, and already see them more or less there and it requires so much energy to keep up with it, that I just turn them over and go over to my board and think from zero almost and I go over and scratch on a thing. Iʼve got all these ideas and theyʼre just so difficult that I somehow choose to, you know, take an alternative course which takes me back to having nothing, if you like.

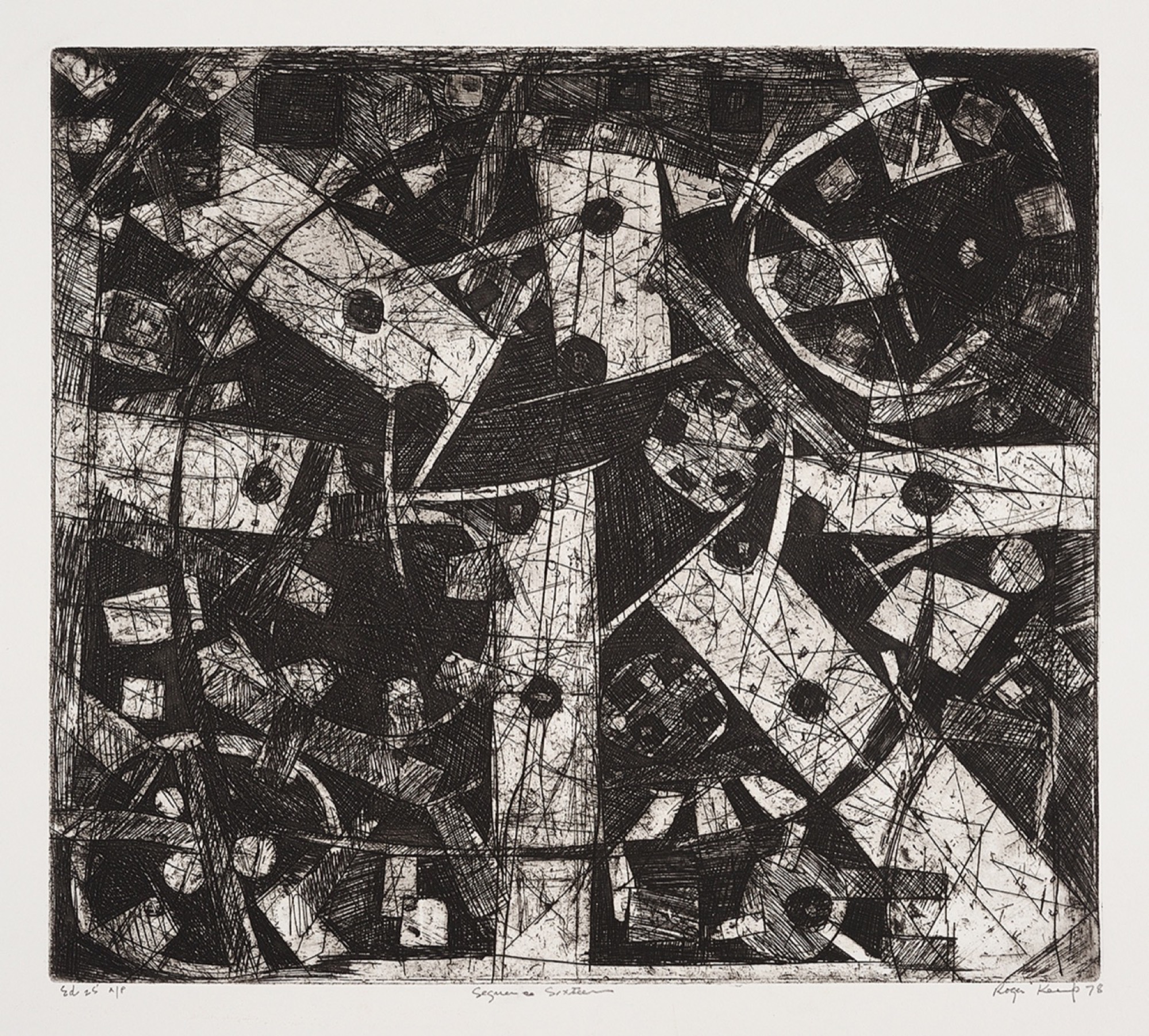

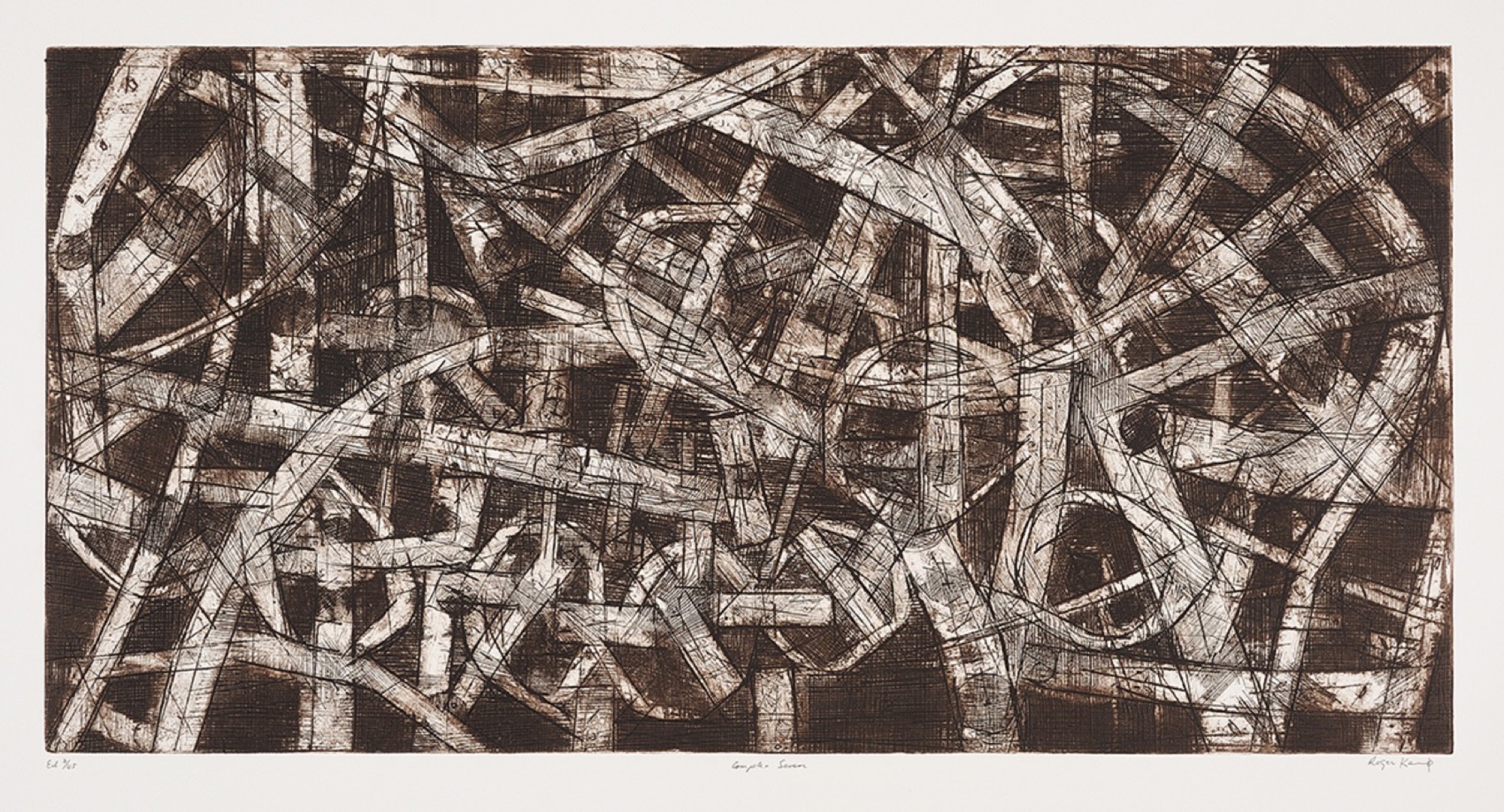

The titles of his work abound with vague portent, grasping for a universalist logic that can carry the heavy weight of his inarticulate thought-process: “Sequences … Concepts, Movements, Circles, Rhythms, Complexes and Horizontals”. For Grazia Gunn, his work was categorised by its “sense of relentless repression” that was connected to “an unwillingness to show the wider boundaries of his work”. Helen Hughes has called his “long-form verbalising” a form of preparatory “transcendental drawing practice”. His captive audience, then, his blank sketchpad.

Despite (or perhaps because of) his social idiosyncrasies, Kemp inspired a deep respect in local art circles. By all accounts Baldessin and Kemp got along well and had a “special bond”. Baldessin had a little mysticism to him too, albeit more of the self-cultivated variety. He was stylish, sexy and a little unknowable. This mystique helped him develop a band of disciples. John Dent, one of his assistants, memorably described Baldessin as a circus ringleader, “surrounded by a cast of strange animals, directing by gesture”.

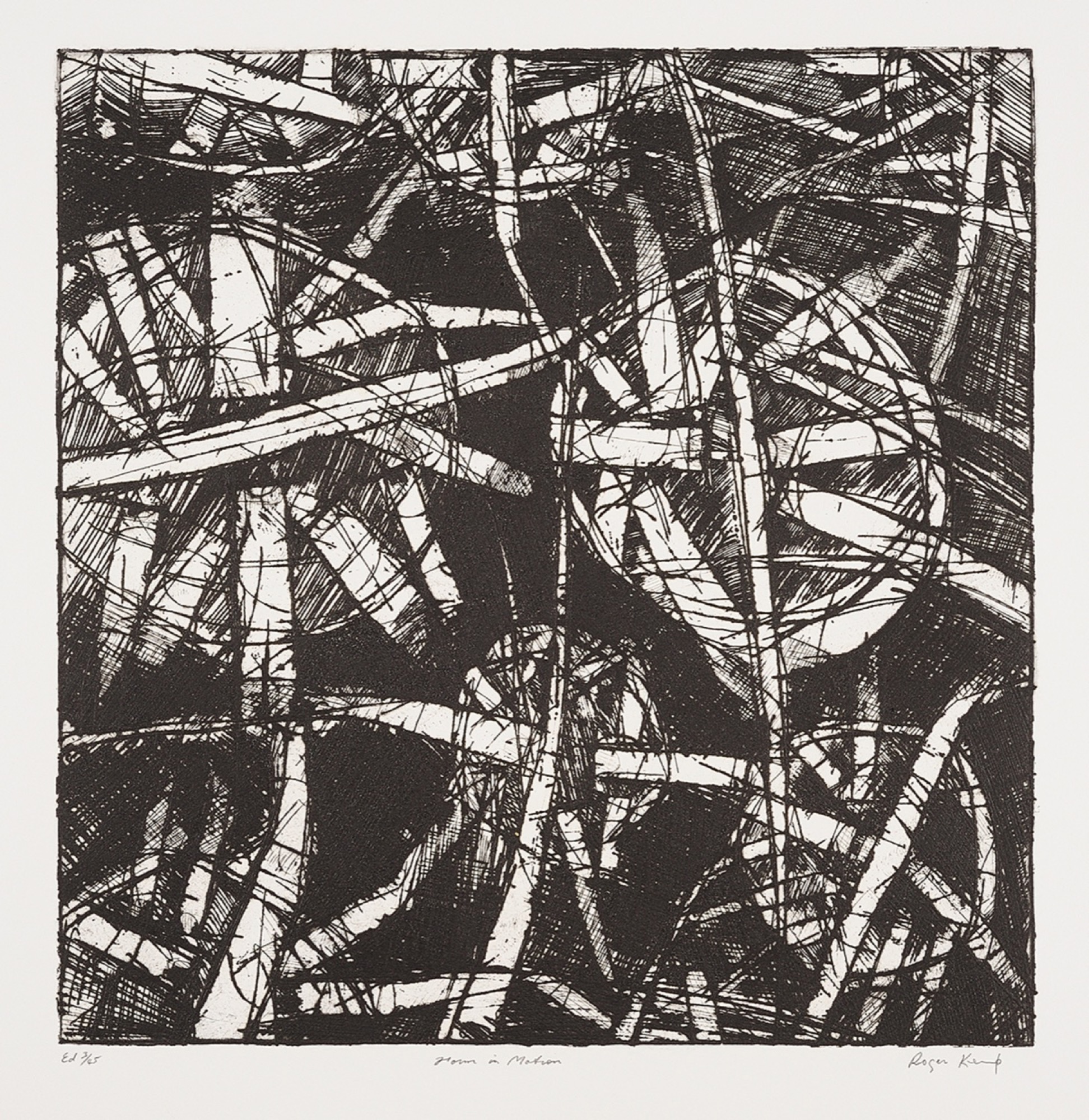

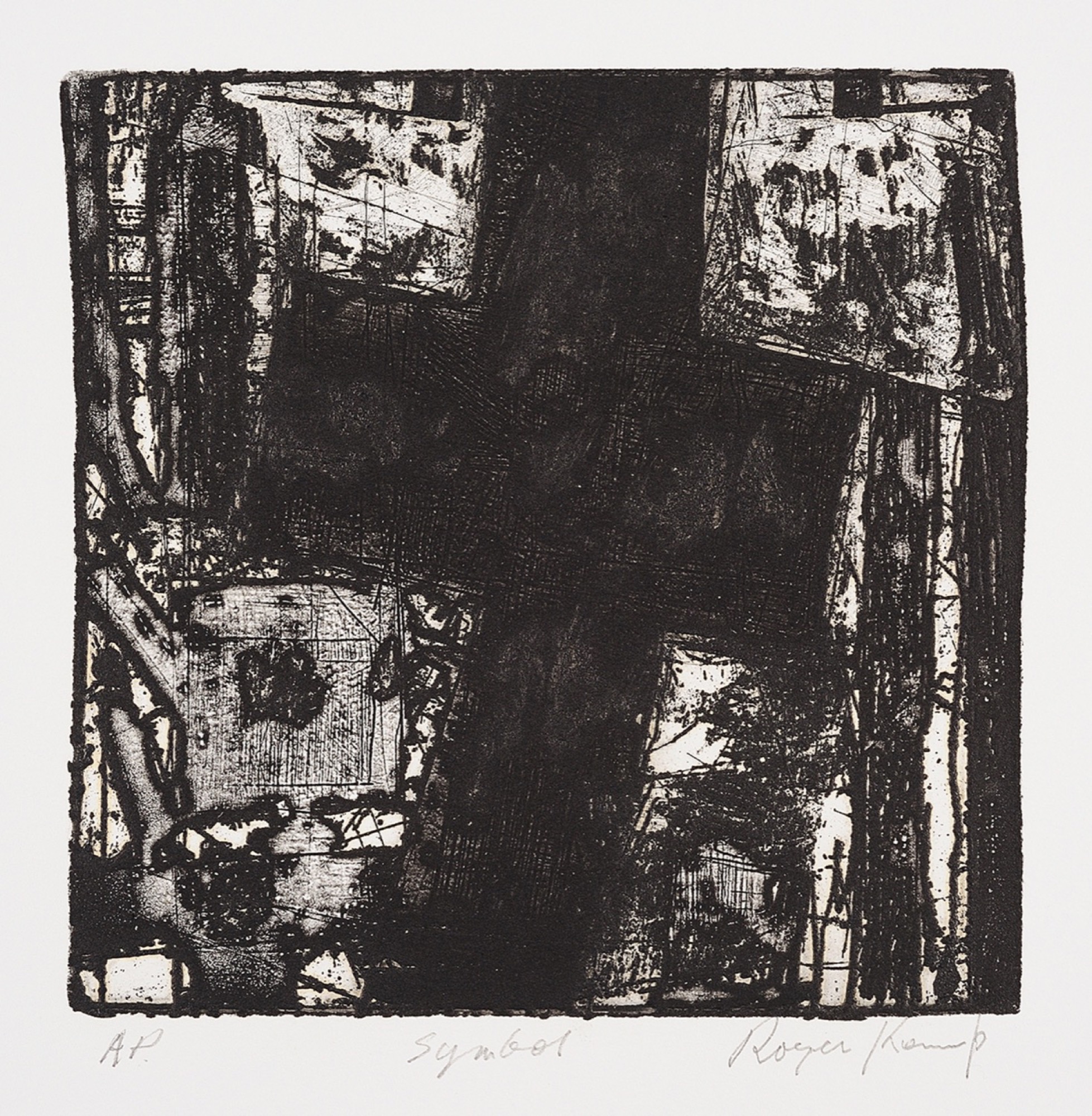

With the circus assembled, Kemp was ushered in to play with some plates. Charles Nodrum Gallery is showing one of his earliest Winfield prints, Symbol (1972), which features a dark, advancing crucifix form. Kemp used a screwdriver to scratch the cross-form into the bitumen, and for this DIY reason I think you could confuse it with one of John Nixon’s more expressive prints. Kemp quickly moved toward more expansive compositions, but he retained his brute technique. Onlookers were impressed with his aggressive approach to the metal plate; Adams described him “fully absorbed, scratching and gouging at a furious pace”. The zinc-plates used at the Winfield were quickly over-bitten by acid, leaving a constellation of inadvertent, corroded marks.

Baldessin’s primary intervention in Kemp’s print development seems to be the encouragement to go bigger. With a plan to start marketing large prints, Kemp was set up with two metal plates that measured about one metre by one metre, to make his celebrated circular form Relativity (1972). This is a common way that a printer might encourage an artist who is new to printmaking: aim higher, think bigger, etc. But scale was not an issue for Kemp. He was used to making enormous canvases. Consider this description of his painting practice:

Iʼll be, you know, just casually sketching a little sketch no bigger than that … I just draw and I say, ʻOkay, that looks good. I think Iʼll paint thatʼ. So I go to my studio and look at it and say, ʻWell, yes, twice, three, four times the size of that which would make it up to about three feet, that would be goodʼ. But before I have it down, itʼs already multiplied about three or four times, you know … It will probably finish up about 20 feet long … It generates its own force … Then Iʼm going like hell to try and catch up to it, you know, and itʼs quite a problem.

While in London just a few years earlier, he had made a monster work over seventeen metres long. I am sure Kemp didn’t need too much encouragement to tackle something one-metre in diameter.

So, while Relativity may have been a relatively small-scale for Kemp, it was all the Winfield printers could handle. They couldn’t physically print even this size and needed to make a composite work out of printing two plates separately. Scale is one of the things that distinguishes the cottage-industry of fine art printing in Melbourne from international commercial art printers. Increasingly large prints were a hallmark of prestige workshops, such as Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, printing for artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist and David Hockney, who each inspired mammoth logistics for their oversized works on paper. But scale wasn’t the only restriction at the Winfield.

Curator Hendrik Kolenberg recounts that the Crossley Workshop did not aim for consistency when printing an edition and that “few of Kemp’s prints within early editions are of like quality”. Baldessin’s printing assistants were “too busy” to keep a formal archive of the prints they had worked on, and they rarely actually printed the full edition of any one image. Kolenberg forgives this lax practice, reminding us that “this realistic approach was not uncommon amongst printmakers”, but it sure is uncommon in a commercial workshop. It’s the main reason why a printmaker would use one.

The unprofessionalism of this operation and its frenetic activity is why curator Roger Butler has insisted in his recent history of Australian printmaking that “this arrangement (at the Crossley Workshop) should not be compared with the European (and American) model where print technicians and printers studied for many years before being permitted to work with artists”. Ultimately the Winfield Building studios illustrate the hazards of art spaces that are semi-commercial but perceived as communal, when in practice and in politics they are anything but. Baldessin was not a master-printer, and he wasn’t really a traditional boss or employer. He was one of those figures that exert a strange power over their surrounds.

Baldessin certainly made room for Kemp at the Winfield, and he also made the Winfield a multi-generational space where genuinely profitable art skills could be passed on from successful elder and mid-career artists to young assistants. Yet Neeson, who had introduced Baldessin to the Winfield, ended up as a casualty of the workshop’s informality. After years of establishing Baldessin’s studio under their gentleman’s agreement, mid-1974 he was non-amicably informed that he would have to leave his workspace, and in the acrimonious events that followed much of his art and personal materials were damaged or destroyed. His section of the studio, incidentally, was taken over by Kemp.

What does this anecdote illustrate other than the all-too-common pettiness of places of work that are also contrived as sites of community? Our local history of ambitious, communal art spaces is shallow (barring, of course the monumental historicisation of John and Sunday Reed’s home ‘Heide’, a deep scholarly well achieved with the exceptional resources available to the Heide Museum of Modern Art). Perhaps there is hearsay knowledge about the late John Nixon’s efforts to make room for fellow artists, but there is little sustained research there too. Kemp and Baldessin were two artists given to mystifying their practices, but in this anecdotal account their peer-to-peer relationship illustrates both the power and the pitfalls of informal mentorship.

It occurs to me that with the recent announcement of a $2.6 million “activation program”, which would see the City of Melbourne “reinvigorate” the shuttered shopfronts of the CBD with a post-lockdown plan to temporarily, non-sustainably, dangle no or low rent to “artists, budding entrepreneurs and artisan makers”, it might be timely to think more deeply about historical models of shared art spaces in Melbourne. Printmaking workshops, requiring as they do either commercial agreements or collegial tutorage, are perfect sites to imagine the meeting of two or more artists and to think about the sustainability of the collective efforts that we may (or may not) choose to replicate.

Victoria Perin is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne.