Richard Bell: Dredging up the Past

Rex Butler

In the recent rehang of the Australian collection at the Queensland Art Gallery, visitors before entering the gallery have to walk under Richard Bell’s Judgement Day (2008), which hangs on a wall above a doorway. “Australian Art Does Not Exist”, Bell’s painting declares in a nice self-contradiction because both Bell and his art are just about as Australian as you can get. And perhaps more profoundly because for the past 35 years Australian art has staked its very identity on being able to say that it does not exist.

Of course, what Bell’s work opens up is a distinction between its enunciated and its enunciation. On the level of what is said, it is true we can’t find much that is distinctive about Australian art; or it might even be said that white Australian art and culture has no right to exist because it owes so much to the original occupants of the land, which it has never even been tempted to repay. And yet on the level of its saying, Bell’s work is profoundly Australian: it is only an Australian artist who has the right to say this, and even when Bell says it we know that he is saying it only in the name of a future art of Australia, one that on some far distant day might be worthy of the name. (Why make a painting like Vincent and Gough, as here, otherwise?)

Bell first became well known when he won the 20th Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award in 2003 for a work entitled Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem) (2003), which featured another similarly paradoxical injunction, “Aboriginal Art is a White Thing”, which cannot really be understood outside of its apparent opposite, “Australian Art is an Aboriginal Thing”, which features in another of Bell’s paintings. The enigma, of course, is that both statements are simultaneously true, while each appears to rule the other out.

Only someone like an artist could get away with such logical self-contradiction, although Bell himself has often disclaimed the title. He speaks of himself as an activist or even a prankster, although I prefer to think of him as something of a psychoanalyst. I’ve seen him in public performances somehow get audience members to say such things as “I’m no racist, I’ve got Aboriginal friends”, before rudely interrupting them and having them think – without him having to say anything – why what they just said was wrong or indeed self-contradictory. (On the level of the enunciated, sure, they are not a racist. But in their saying of it, they are.)

Bell once made a devastatingly funny video called Scratch an Aussie (2008), in which a gorgeous bunch of sunkissed Gold Coast teenagers dressed in swimming costumes confess themselves to the black Freud Bell, complaining about such things as people calling them names and other kids stealing their mobiles at school. The white-bearded Bell just nods and winks at the camera with a subtle smile crossing his lips. It’s a video that should be mandatory viewing for every artist wanting to deny their “white privilege” while dressed up in the equivalent of their gold swimming costume. They should just listen to how racist they sound, as should the people listening to them because you can only denounce your “white privilege” to someone who shares it with you. White people can’t get rid of their white privilege in Richard Bell’s world. They are it. It’s who they are. It’s what defines them.

Bell’s Dredging up the Past at the relocated Gertrude Contemporary on High Street in Preston is a sad show, mostly because of where you have to see it. Bell’s seven canvases sit antiseptically on white plasterboard walls above a shiny concrete floor in a large soulless space that looks like an empty luxury car dealership. When you enter the people sitting in the main office don’t even raise their heads from their computers. They’ve obviously got better things to do than actually say hello to anyone walking into their gallery. Absolutely lost is the grimy intimacy, the dirty walls, the squeaky floorboards of the old Gertrude, with its spectacular front window facing the street, through which I remember seeing one night coming out from a meal at a nearby restaurant just about the best work of art I’ve encountered in Melbourne over the past several years, Frédéric Nauczyciel’s spectacular dance video A Baroque Ball (2014).

There’s nothing like that intimacy or shared sense of community in the new space as the traffic roars past and your footsteps echo hollowly. And Bell’s work seems cold, mechanical, too harshly lit. Just paintings on the wall and not provocations, invitations to argue with him but mostly with oneself.

There are the usual polemical declarations: “We Have to Share” in Both Ways (2017); “You come from Here”, written on a map of Western Europe in Poor/Lean (2017); and “Thank Christ I’m not a refugee” sighed by the head-back swooning woman in Great Scott! (2016), the latest in a series that obviously started off as a parody of the heterosexist clichés of the Lichtenstein originals but has now come dangerously close to becoming a cliché itself.

There are even the mandatory moments of hope or redemption – like Bell’s striking depiction of the presence of Australian runner Peter Norman at Tommy Smith and John Carlos’ black power salute at the Mexico Olympics, all depicted now standing on the same level – with the bringing together of Leonardo and Rover Thomas in One More Hour of Daylight (2017) and a version of Mervyn Bishop’s celebrated photo of then Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pouring sand into the hand of Gurindji leader Vincent Lingiari in a moment that is said to mark the beginning of the contemporary Aboriginal Land Rights movement, Vincent and Gough (From Little Things Good Things Grow) (2018).

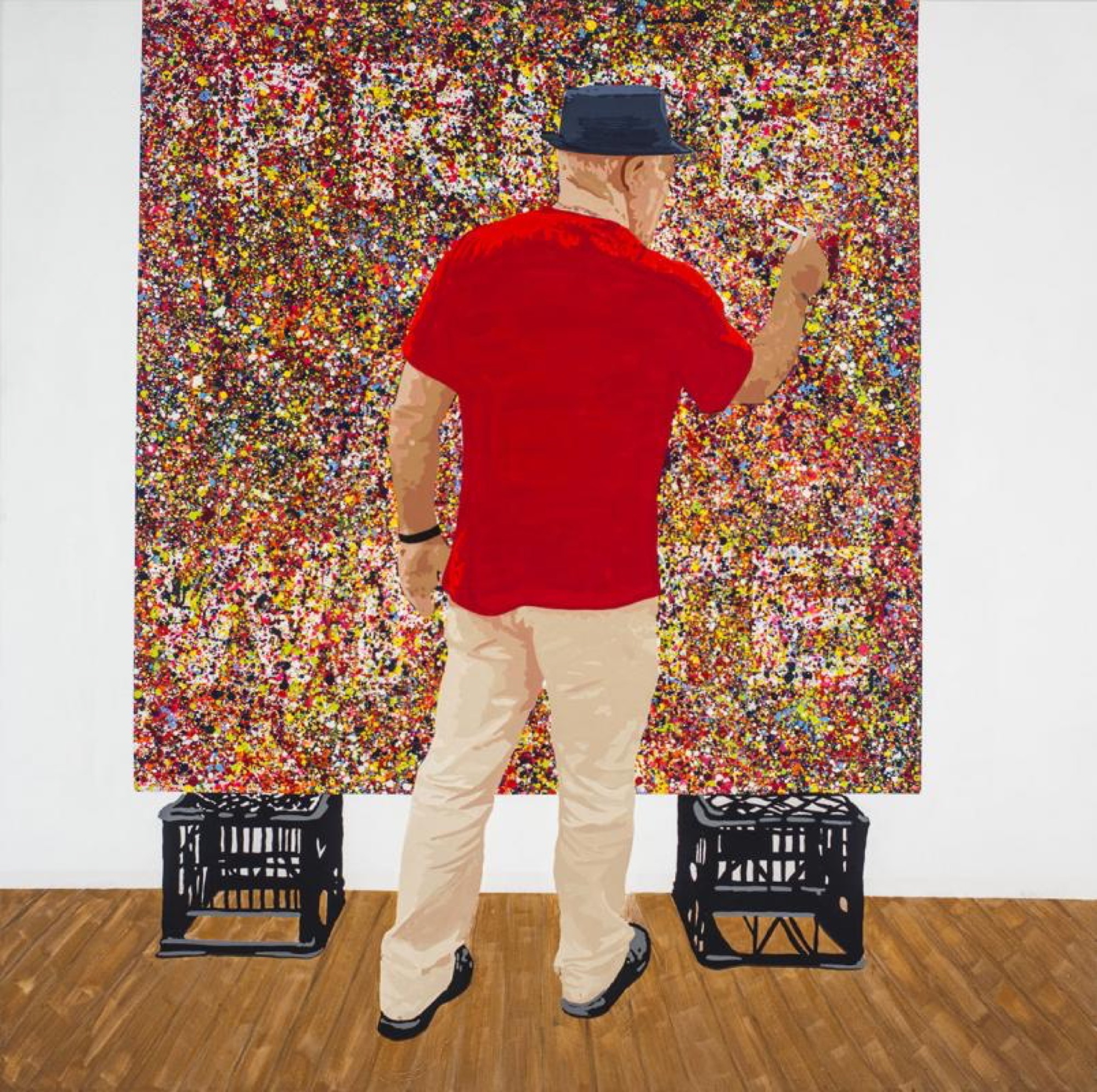

Perhaps the best – or at least wittiest – works in the show are the couple Always Will Be (2017) and Working for the Man (2017). The first features one of Bell’s trademark kaleidoscopic paint sprays, within which can be found the words “The Price is White”, while the second features Bell himself painting the work, set up on two black milk crates. Amongst the humorous – or at least ingenious – aspects of the works are the way Bell has somehow been able to make his indexical paint spatters appear smaller for the painting-within-the-painting of Working for the Man. Also the fact that with such a potentially messy work and all of that paint splashing around we see Bell standing in his trademark luridly coloured jeans, black leather shoes and hipster porkpie hat seemingly untouched, apparently making an already finished work. Finally, though, the mise-en-abyme structure of the second work as it were insinuates Bell’s labour and identity as though between and within the dots of the first. It’s not just the white of the work’s slogan we have to look out for, but the dispersed black marks of Bell’s presence.

Across over the other half of Gertrude’s split gallery is a thoroughly dispiriting show by the New Zealand artist Shane Cotton. In fact, Gertrude in its pairing of the two artists is really just replaying a show held in 2005 at the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane that put together Māori artist Peter Robinson and Gordon Bennett. But Cotton’s work here, which makes up an exhibition called Black Hole, seems uninterested, perfunctory, merely a series of substitutable black faces or masks arranged indifferently around the gallery walls.

Maybe the best thing on High Street Preston at the moment is the great second-hand bookshop a little way up on the other side. After visiting the show, I wandered in and bought all the Ross MacDonalds and Margaret Millars I could lay my hands on and had a long chat with the guy who worked there. In the cluttered, curated and lived-in space of the bookshop, I could feel that someone was exercising some kind of individual taste and preference. What a difference from the anonymous showroom of contemporary art opposite.

Title image: Richard Bell, Vincent and Gough (From Little Things Good Things Grow): Gertrude Version, 2018, Acrylic on wall, 180 x 240 cm. Many thanks to the Telfor family for their assistance in creating this work, especially Rebecca and Emily Telfor.)