On Campus

Giles Fielke

Curated Raimundas Malašauskas.

‘It is said that the voice rips open reality’. This is apparently the only utterance I had thought worthwhile writing down into the blank, A5-sized notebook I had been supplied with at the beginning of On Campus. I cannot recall who suggested this maxim in the course of the two-day program that took place at Monash University from February 14-15 this year. Otherwise the thin, ochre-coloured cardboard cover, bound simply around 400 empty white pages, and the few loose leaflets splicing the book as a commonplace materialisation of subjective potentiality, still carries the faint smell of a scent garnished by George Kara, a local perfumer participating in the event. Elusive, hard to place, struggling against the organic, it reaches out to trigger a memory. This olfactory key persists even as I thumb through the almost entirely vacant pages four months later. The rip, or tear, is a precise image for the staged nature of On Campus, which left me staggering over the expansive landscape of novel possibilities present in the conceit.

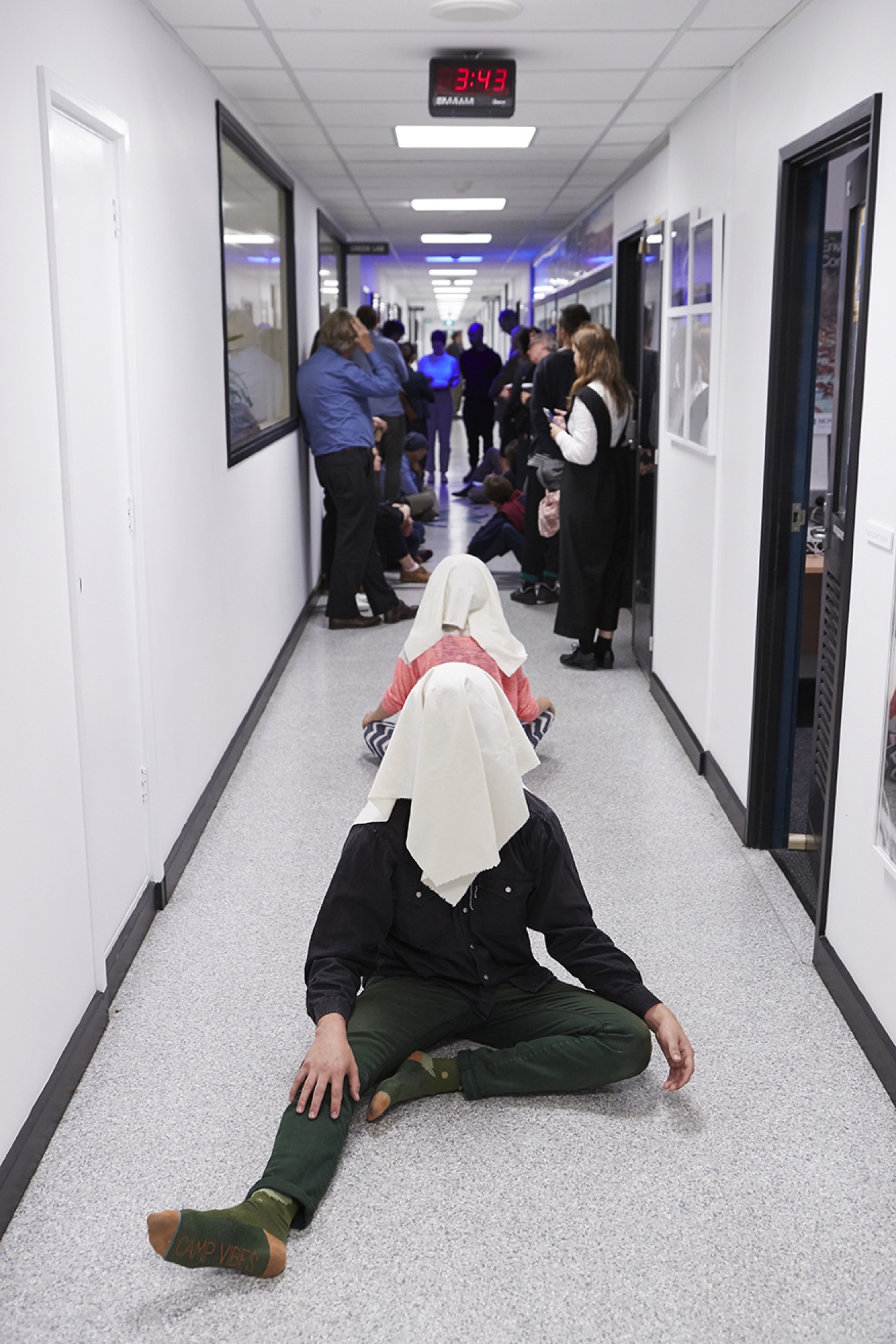

During these two days (10pm–5pm), the artworld experience is administered as a clinical event. This is an idea not to be resisted, but rather embraced. Just prior to the onset of the academic year Raimundas Malašauskas, a curator and facilitator of contemporary art (think of the role played by an anaesthetist during operative surgery), was invited to stage the two-day event in just this way. The experiment was apparently intended to act as a secularised ritual re-opening of the institution, just in time for the students to arrive, cautiously enthused for semester 1 of 2017. Before day’s end there are tears, certain realisations; a group is formed, storming, norming, adjourning. Then the utopian spirit of the endeavour collapses just as it is supposed to. Looking back, Bruce Tuckman’s educational psychology from the mid-sixties may just have been the retrospective hypothesis that Malašauskas had asked for at the end of the program. Learning to perform was the content of the exercise.

Organised through the Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) and supported by the faculty of Art Design and Architecture (MADA), Malašauskas was invited to inaugurate the new year (he also gave a lecture at the fine art post-graduate seminar the day after On Campus). Collaborating and co-ordinating a number of locally based artists –most alreadyloosely affiliated with Monash – the event took place with the convening of this newly formed, closed community of participants and their guests. I received my unexpected invitation via email: ‘Dear All, Please find attached information for On Campus. Scroll through for the event schedule…’ So I wasn’t sure what exactly to expect, but I’d certainly felt included, exclusive, even a little bit self-conscious for my involvement. I was also somewhat embarrassed about the privilege of being privy to some kind of internal mechanism.

This was surely going to be some kind of luxury artistic delight, something not needed by anyone. To brace myself I imagined what it would be like to go on a professional development or team-building weekend with a mix of senior and mid-level management. This was the art-world version of a similar sentiment, but it promised to be a bit more fun (more fun!). Would we all lose our inhibitions? Nearly. Coaxed by Stuart Ringholt’s model for museum tours, I found myself naked and alone with Nicholas Mangan’s Bitcoin mining mainframe – a remainder from his Limits to Growth exhibition now permanently installed in the basement of the Caulfield museum – I considered taking a selfie to upload to Instagram. Cheeky, but surely there was a way to communicate what was happening here. Only the voice rips open. It destroys the delicate reality of the hermetic experience.

If the orginal domain of aesthetics is not art, but reality, the complex suture of the musuem setting struggles to contain this program for contemporary art. Participants in the event as well as the schedule are printed on a bookmark inserted into my expectant journal. The Open Spatial Workshop exhibition, Converging in Time, had just opened at MUMA but was to be kept closed for the duration of On Campus. The gallery’s glass entrance and windows had been temporarily covered with dark curtains taped up with Gaffa. Nineteen participants were listed, plus more were promised. Maybe this meant me?

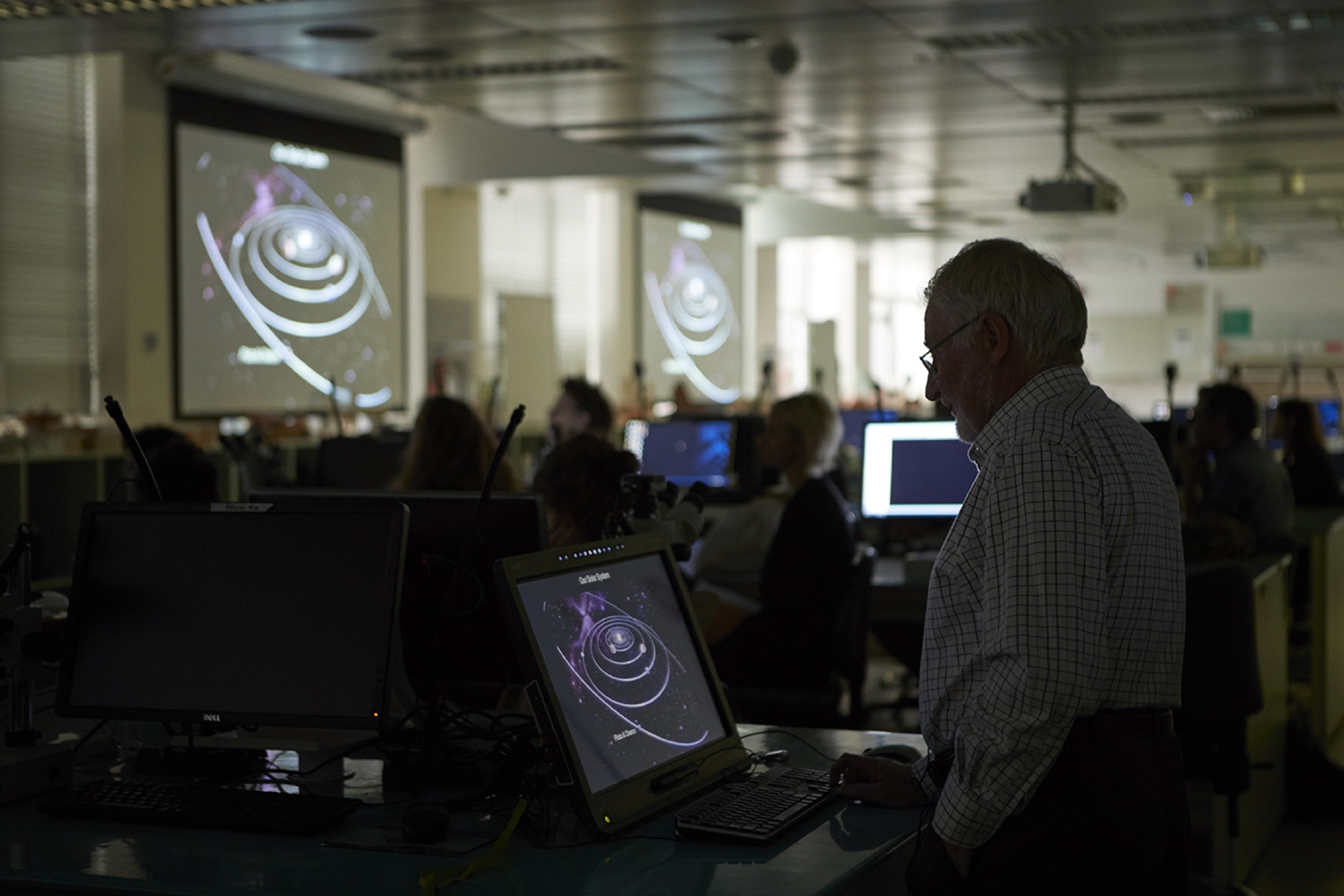

The publication design by Malašauskas, in collaboration with Žiga Testen, acknowledged the institute also appearing on a postcard slotted into the notebooks. Dissemination and travel emerged as the dominant aesthetic. Marcus Lutyens’s voice appeared disembodied from his physical presence in Los Angeles. The School of Biological Sciences in the Faculty of Science at the Clayton campus, was thanked in advance, leaving a clue as to what was going to take place. A personification, Performance watering architecture, painting, sculpture and science by Audrey Cottin suggested something further. Artists Prue Lang, Tom Nicholson, Agatha-Gothe-Snape and Brian Fuata, as well as others, presented some aspects of their practices performatively in the context of the science labs at Clayton campus. Nicholas Tammens read a Donald Barthelme story in a Mid-West American accent while we played with digital microscopes and examined the contents of our hand-bags and pockets. Others came and went – Liquid Architecture’s directors Danni Zuvela and Joel Stern transcribed text from the Committee on Australian Universities, the 1957 Murray Report, into a chorus about the good university sung during a bus ride between the campuses. Some never even arrived. Nicholson’s intervention was read in absentia by MUMA director Charlotte Day – recalling the Whitlam declaration of free tertiary education at the Caulfield Technical School in 1973. The curator of the Monash art collections between 1975 and 1980, Grazia Gunn, gave an interview with Malašauskas which was also included as printed material. But Gunn was also present for the two-day event, and artist Lizzie Newman had installed a ten-work selection of mostly contemporary pieces from the collection, the earliest being Peggy Perrins Shaw’s watercolour and pencil drawing, Venite et vidite (1982). Malašauskas had us moving the whole time we were in the small gallery, a curatorial contest between curators becoming some kind of constructive and progressive battle of wills.

In a lecture given at Artspace in Sydney a few days after the On Campus event, Malašauskas posed the question: ‘Will the projects generate new and more satisfying modes of connecting, relating and feeling? Will I continue to know as much through art as previously?’ For the pretensions of a contemporary guru who is always within the artworld environment, this kind of thinking symbolises what it means to be contemporary, in the sense that one approaches the world with an attitude, or style that is presented to art as currency. On his website, rai.lt, the Lithuanian curator points to his collected writings, published in 2012 by Sternberg Press. Paper Exhibition: Selected Writings presents an anthology of writings wherein the introduction, by Maxine Kopsa, enthusiastically suggests the ‘Rai-factor’ is what gets added to the mix. Indeed the playful nature of this facilitator of the art-event means he is always teetering, in a deliberately cultivated precarity, on the edge of some initiative or fleeting idea that threatens to lapse into idiocy. He shows us a Soviet-era children’s television as if it is a profound media fossil. Like Nietzsche’s tightrope walker, Malašauskas is the necessary figure of the inevitability of spectacle. It is in this sense that the generosity afforded to him by his hosts is both risky and invigorating. It is a pity, however, that it seems to be a signature of Australian art that a man such as this must always arrive from the North – oftentimes mainland Europe – as if the only way such an indulgence can be justified is by way of a deferred gesture to the more seriously embedded authenticity of Western aesthetics that is believed to have come from some kind of geographically locatable well-spring.

Indeed, Malašauskas’ recent staging of Dexter Sinister’s The Last ShOt Clock, at the 12th Baltic Triennial in Vilnius, suggests the elaboration of a new wave of open aesthetics, with the work-in-progress as work as the ground for the festivalism of the art-event. Australian historians of contemporary art, Charles Green and Anthony Gardner, have recently attempted to address this type of emergent mode for the encounter with art as a symptom of neo-liberalism in their book Biennials, Triennials, and Documentas (2016). In fact the discourse of contemporaneity could be just as easily wedded to the conceptualisation of the generalised condition of post-historical malaise. In desperation for experience, the event must be staged, and it must be well-performed.

The tear in the event, the ripping of the voice, was recapitulated in the final parts of the schedule at the end of On Campus. Dignified by the presence of anthropologist Stephen Muecke and his casual explanation of curator-participant Camila Marambio’s presentation of Arthur and Corinne Cantrill’s 49-minute film Two Women/Seven Sisters (1979), the ridiculous became the sublime. The Cantrill’s 16mm film is no longer permitted to be shown in public (like most 16mm film these days), particularly due to the fact that the collaboration with the Pitjantjatjara people from the Western Desert was never formally authorised by the community. Part of their ‘Grain of the Voice’ series of four films, the abstracted landscape images were edited by the Cantrills in response to the songline recorded and played back, apparently un-edited, as the soundtrack to the film. Beforehand Marambio read the group some of the correspondence she’d had from Corinne in the last few days, by way of explanation for the film and its making, and its screening in the gallery. When the film had been edited originally it was to be screened for the Anangu following their collaboration in the making of the film. The Cantrills had returned to find them gone, they had left to attend an inter-tribal gathering that was taking place elsewhere, their connection was missed. Arthur Cantrill has recently been very sick, Corinne explained in her email to Camilla, who then recounted it to the group. He had woken up a few mornings before the screening scheduled for On Campus and had experienced a bloody nose that could not be stemmed. She’d had to take him to the hospital, where he remained for observation. There was blood everywhere in their house. Muecke, for his part, offered his explanation at the conclusion of the screening – the bleeding was a part of the songline they’d recorded. Blood was often used to attach feathers to the body, he explained. The screening had been the event that had triggered a decades-due blood letting. If this was an allegory for the aesthetic of the work, it was unbelievable. But we’d all been brought into some kind of experiment in group psychology, and in this experiment anything was allowed to be possible. The gallery was the clinic, and we’d been subjectively dismantled. There was, therefore, a truth to the situation. What it was no one could say. The tear had already been sutured.

A few days before On Campus, David Homewood and Luke Sands facilitated an un-official, one-day exhibition of new works by Zac Segbedzi on the 6th floor of the B-building adjacent to MUMA. ‘Coloured Grids’ consisted of four paintings on jute, four nearly identical gridded representations of the National Socialist flag, the swastika as an emptied symbol for contemporaneity. The normalisation of an aesthetics of the event, relational as well as happening, contributes to a sense that the administration of experience is all that remains. If this is now the standard for culture, the bar has been set quite low. There is, admittedly, nothing at stake in this experiment but the embarrassment of failure (which has also been reified as a positive outcome). Susan Buck-Morss’ writing on aesthetics and anaesthetics in the aftermath of 1989 suggested that Lacan’s mirror stage should be read as a theory of fascism. She then notes in passing that the word narcissism shares a root with the word narcotic. Here the anaesthetist’s task is to ‘manage’ the rip or tear that appears in the fragile body, the social body that sees in its future the inevitability of its fragmentation. The only necessity is to progress towards the silence that is the culmination of this utopia. Here, perhaps, is the meaning of the emphasis upon performance, that it can exist ony for as long as the body does.

Giles Fielke is a writer and musician working at Monash University and the University of Melbourne. He is the Business Manager of the AAANZ.