Reading into Things

Audrey Pfister

Over the past few years I’ve made it a habit to begin each day by making myself a coffee and reading. Much of the time I’ll zone out, I’ll bite my nails, and I’ll get confused following the text. One of my favourite writers, Jordy Rosenberg, author of Confessions of the Fox and “The Daddy Dialectic”, has said that reading and not understanding, and keeping on reading anyway, is one of life’s pleasures. He poetically elaborates that being lost in this way is related to the development of “a political life”, which he describes as “the extension of ourselves into the world and to the forming and care for the collectivities that we will need to survive this world, and that, perhaps more importantly, we want to survive us into a different future.” Pushing through the difficulty of reading can remind us about the contradictions, complexities and chasms that constitute life, but it can also remind us of our desires. So what does it mean to take this kind of approach—reading, reading differently, learning, and sometimes not—to objects, materials, and sculptural work?

It’s an approach that Pari’s first exhibition for 2023, Reading Into Things, offers. Co-curated by Pari Directors Samuel Kirby, Naomi Segal, and Alexander Tanazefti, the exhibition displays a range of works from local and inter-state artists Simone Brown, Harry Copas, Sally Craven, Paula do Prado, Louis Grant, Emily Greenwood, Lachlan Marley, and Othy Willis. Many of the works evoke queer, feminist, and/or ancestral knowledges, but perhaps not in the ways one would imagine (think NGV’s very pictorial and literal QUEER exhibition, or Australian Museum’s “Progress Shark”. Like Rosenberg’s approach to reading, the curators of Reading Into Things invite attentive, intimate, entangled and open-ended ways of seeing. Reading Into Things has a pedagogical sensibility without it feeling didactic or prescriptive.

The act of reading/seeing as an enduring and complex process is introduced succinctly in this exhibition by Lachlan Marley’s sculpture, Untitled Bar With Chemset and Aluminium (2023). This work consists of a bar, mounted eye-level on the wall, slanted slightly upwards, and wrapped with close-up images of eyes (both animal and human) textured in wheat-paste style. On top of the bar sits a jumble of obscure letters and symbols, rendered in aluminium. The artwork’s eyes look back at you looking at them, as you try to figure out what the hell it all means. If it seems ambiguous and cryptic, that is precisely the point. As is noted in the room-sheet, Marley engages closely with his materials, plumbing their unique properties to produce non-traditional and unexpected results—in this case, aluminium and Chemset are combined to look like slag. Untitled Bar evokes the techniques of reading and seeing, only to play with and inhibit them, to expose their limits.

Earlier in the week I had met with Naomi, one of the exhibition’s curators, who excitedly told me about the exhibition and showed me pictures of the incredible works they’d selected. I told Naomi that it all reminded me of Gordon Hall’s 2016 text “Reading Things”, and Naomi tells me that it was that text in particular that inspired their framing of the exhibition. (It’s obvious now—Reading Into Things / “Reading Things”.) Hall is a New York-based artist primarily working with sculpture, performance, and writing. Their work seeks to experiment with and expand understandings of embodiment by tapping into the pedagogical potential of objects. “Object lessons,” as Hall terms this approach, offer “ways of approaching our variously felt struggles against hegemonic methods of taxonomising, cataloging, and controlling bodies, as modestly offered resources toward imagining more expansive forms of embodied life.” For both Rosenberg and Hall the commitment to reading difficult things is related to understanding our political and embodied life, while also imagining better and different ones.

A key focus in Hall’s text is a functionally-mysterious found object known as the “slant step”, a linoleum-covered wooden stool-sized object that slants at a forty-five degree angle, making it unusable for sitting or standing on. The ambiguity and non-functionality of the step, purchased in 1965 by US artists William Wiley and Bruce Nauman, famously inspired a number of exhibitions and writings. For Hall, the slant step is a key example of how objects can act as a kind of teacher, pushing artists to learn, for example, the importance of “slowness to assign identification in the moment of encounter.” Looking at Marley’s strange, slightly slanted Untitled Bar on the wall, I can’t help but draw a parallel with the step—both produce a more effortful type of reading, both produce perhaps more questions than they do answers. While one object is found and the other is made, both urge us to take time with what we see and work through our received aesthetic and social categories.

Louis Grant’s works in Reading Into Things unequivocally embody “object lessons”. For both Hall and Grant, abstraction and formal reduction are strategies for unbecoming, fluidity, and resisting easy categorisation and representation. I lay in silence, but silence talks (2021) is an immaculate sculpture by Grant made from a magenta bowling ball-sized blown-glass sphere, sitting on top of blue glass in the shape of a small upside down cup. The curators have installed the work around a bend in the gallery corner so that it’s on display in the gallery’s large shopfront windows. But this also means that if you want to view the work inside the gallery you have to peer behind a wall around the small corner and get intimate with it, which activates a kind of awareness between your body and the object. The artwork is subtle, and silent as the title suggests, but there is more to its minimalism.

Grant’s objects are mysterious and opaque, and they’ve utilised formal abstraction as a means of expressing the unfamiliar. The ambiguity, in this scenario, is used to challenge conventions of heteronormativity. Grant’s second artwork, I don’t want to live in a man’s world anymore (2022), consists of two beautiful hot-cast and cold-worked glass squares standing in parallel on a plinth. One is blue and one is pink—the colours suggest gender signifiers, codes, and gender reveal parties. Here Grant’s technically beautiful and formally minimal objects offer a different way to think about identification—the reading of bodies—under a hegemonic binary that they find (as the title indicates) unbearable. Abstraction is embraced here as an alternative to the politics and demands of representational visibility. It aims to resist easy legibility in a world that constantly demands it. It is a reminder that queerness is not one thing. Such an approach places Grant in dialogue not just with Hall, but also local artists like Spence Messih, whose glass-based works teeter on the edges of abstraction, opacity and recognition, and an understanding of gender as malleable and detachable from the body.

Othy Willis is another artist whose work strives to endure and resist hegemonic social structures, and find alternative modes of being. For Reading Into Things, Othy takes over one corner of the gallery with Mushroom Paper Ball (2023), made from exactly what it sounds like: paper and oyster mushroom grain spawn. Also in the corner is Retroreflective experiment with plaster shelves and candles (2023), a sculptural composition of retroreflective fabric, recycled paper, plaster, and tall candle sticks that viewers are invited to light. Retroreflective material is often used for its functionality, for its ability to bring something into awareness (bikes, road signs, cars), but here its use is ambiguous. Similarly paper, a material that many of us use and discard daily, is recycled in Othy’s contorted sculptural experiments. Othy’s approach to materials could be understood as a kind of “object lesson” as they’re always striving to learn from working, and reworking materials. Often what Othy has learnt is that these materials need long-term care, and this is usually in the form of repair (stitching, casting, recycling, regenerating), and growing (composting, spawning, fermenting, and regeneration). Similar to the technique of abstraction, Othy’s repairing, refiguring, and recycling of materials re-orders our field of vision and how we see materials. Instead of viewing materials as disposable we can see and wonder what new life or forms they may take.

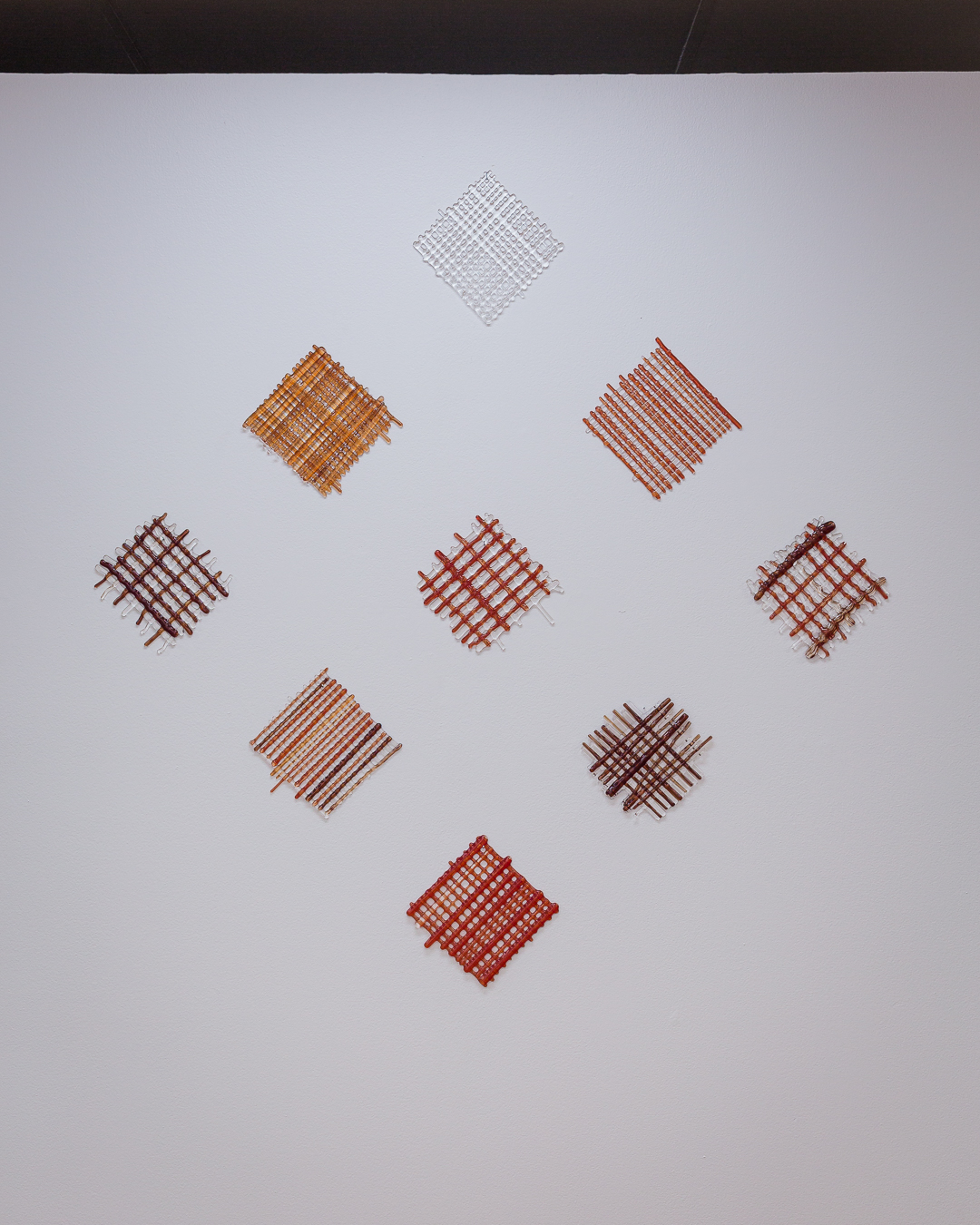

Down the gallery wall from Othy’s works is Emily Greenwood’s Food for Thoughts: A Question of Intergenerational Memory?(2021), which evokes a sense of care and regeneration of intergenerational histories, stories, and practices. Food for Thoughts is a series of nine hand-crafted glass works consisting of woven, criss-crossed orange, red, and brown glass—a reference to Tongan Ta’ovala, a fabric mat to be wrapped around the waist. Similar to Grant’s approach of suggesting embodiment without pictorially revealing it, Greenwood utilises the garment, Ta’ovala, which suggests the body without displaying it. Working with glass has given Greenwood a deeper understanding of the energy and labour behind their ancestors’ Ta’ovala creations. Glass has been an important pedagogical material for the artist—the exhibition text reveals that Greenwood found glass to offer a new sense of delicacy which they related to the sacredness of the Ta’ovala.

Another glass-oriented work in the exhibition, circuit breaker (2021-22) by Sally Craven, imposes onto the centre gallery space. It’s made from a chain of large delicate glass rings that hang from the ceiling to the floor, and ends in a slight curve. Surrounding this glass chain is Craven’s second artwork, a body without organs (2021-2022), a set of enclosed plaster blocks from whose cracks ooze coloured glass. Undoubtedly a nod to Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guatarri’s concept of the same name, a body without organs suggests our bodies to be more fluid and porous than commonly understood, and seeks to understand what the unregulated potential of such a body could be.

Personally, I’ve always been particularly drawn to translucent materials and aesthetics—glass, mesh, ice, tracing paper, clouds, mist. These materials have always felt related to feelings of fluidity, vagueness, obfuscation, and gentleness, feelings I ascribe to different and malleable ways of thinking about gender, desire, and the body. What are the potentials of the body and gender when we untether them from the rigidity and solidity trying to contain and regulate them?

In a way, Craven’s work calls attention to the very fissures of embodied (and political) life that perhaps Rosenberg was speaking of, and that Hall is working through. Many of these works encourage us to read and see objects differently, to be open to the political potentials of not always understanding, to be open to the vagueness, contradictions, and complexities of life. To circle back to Rosenberg writing in reference to reading Judith Butler, he notes that “reading Gender Trouble without understanding it is about making a vow to the fissures that constitute embodiment, us, and our world.” Reading without understanding “has something to do with not giving up on your desire.” And Reading Into Things is completely full with such desire(s).

Audrey Pfister writes, and works in the arts and is currently based in Naarm. They have a Bachelor of Art Theory and First Class Honours in Arts (Media, Culture, Technology). You can usually find Audrey in the library.