Installation view of Re-departures—Works from Melbourne and France at Visual Diary, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

Michael Farrell, Re-departure – works from Melbourne and France

Brendan Casey

On or about June 2021, the acclaimed poet Michael Farrell made his new art practice public on social media. In his mid-fifties at the time, this was a surprising turn. But visual art, it should be said, was not new to Farrell. He had already presented his 2006 collection Break Me Ouch as a series of comic strips while, similarly, in poems such as “The Bush and the Internet are Interchangeable”(2015)—

A wife looks at her husband; a treefrog at a modem. They view the bush from a comfortable position: enjoy wifi by the campfire like a Manet. Five years later the scene becomes unrecognizable

—Farrell displays not only an ironic relationship to the landscape paintings of the Heidelberg school (think Frederick McCubbin’s The Pioneer (1904), but a keen visual sensibility and eye for memorable juxtaposition. And his new art practice did not present a major thematic departure from his poetry. The first soft, technicolour collages offered up in 2021, made with watercolour, crayon, or pencil, were quintessentially Farrell. Like his poetry, they were populated by celebrities (Gertrude Stein eating cake with Agatha Christie), marsupials and monotremes (a platypus playing hopscotch), and more quotidian scenes of Fitzroy life (a car burning outside Farrell’s apartment window at 5:00 am). No, it was the sheer volume of the output that was notable. The multitude of works that Farrell was producing confounded Instagram and Twitter’s algorithms. “Like” one on social media, and you had already missed five more. The machine says, “Please! Enough!” The poet presses “New Post.”

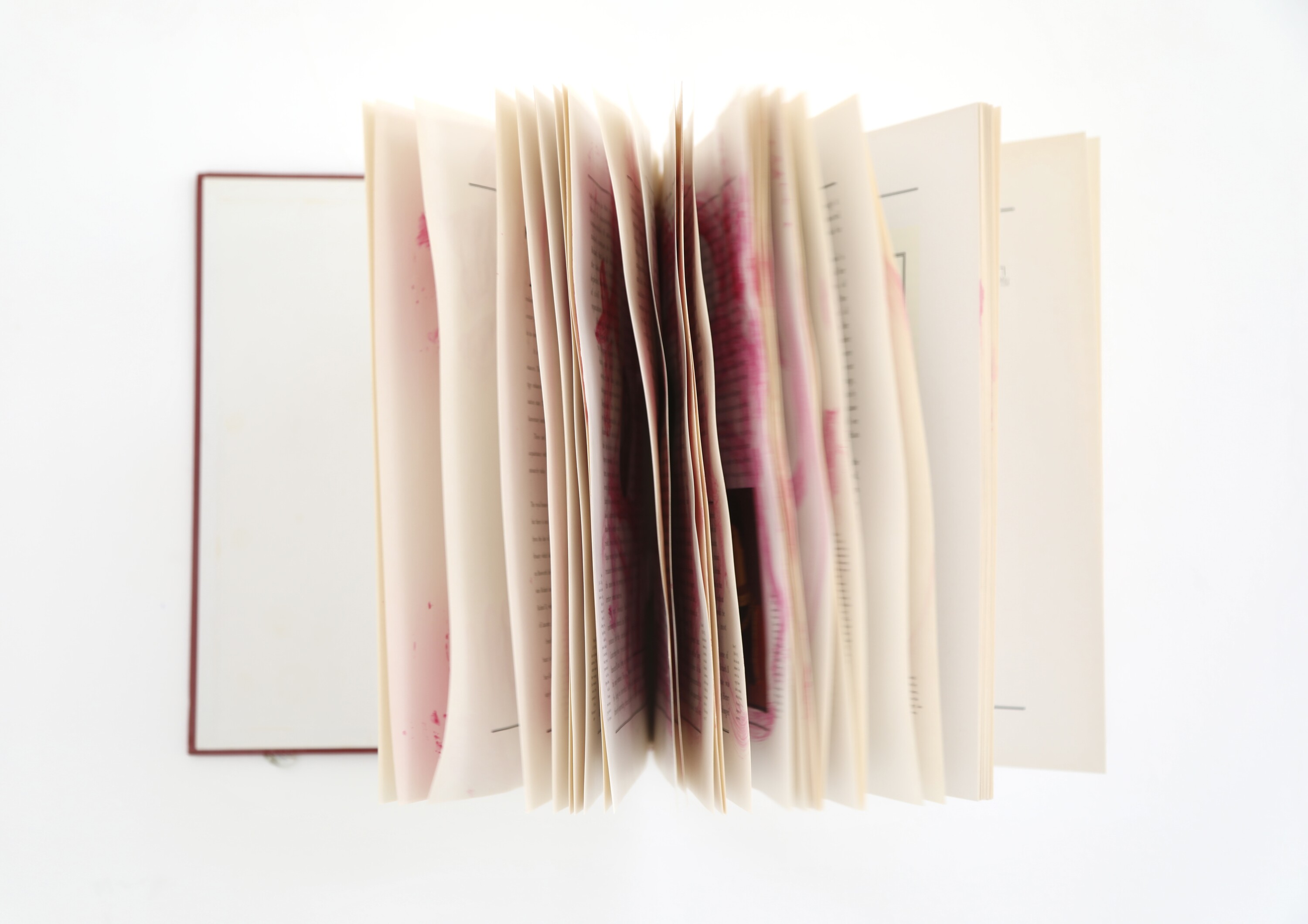

Michael Farrell, 2024, Hate Paintings, acrylic paint on found book, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

Re-departure—Works from Melbourne and France at Visual Diary is Farrell’s first IRL solo exhibition, and offers a survey of his art practice from 2021 to the present. But Farrell might already be too prolific for a retrospective. Asked once where his poetry came from, the American John Ashbery replied: “I’ve conditioned myself to write at almost any time. Sometimes it doesn’t work, but on the whole I feel that poetry is going on all the time inside, an underground stream. One can let down one’s bucket and bring the poem back up.” This metaphor—which Ashbery sometimes changed to a more industrial “mental conveyor belt,” or sometimes to a “mental television”—is a good description of Farrell’s artistic practice. To be a poet is to write poetry. To be an artist is to make art. The more you do, the more you can do. The ambition is to tap into a psychic broadcast that runs without interruption or ad break.

The fruits of this productive doctrine fill the space at Visual Diary: thirty collages, drawings and paintings, ceramics, a ring binder filled with foam prints. Indeed, for Farrell, it seems, installing his exhibition Re-departure was not an excuse to pause; he has painted a portrait of fellow artist Alrey Batol directly on the gallery wall, and decorated the entry door.

All of which may sound exhausting. The world is oversaturated with images, and we have entered a curious age in which poets outnumber readers of poetry. “Poetry faces a Malthusian limit,” observes Craig Dworkin.

Bound by discrepant rates of production and consumption, the readerly economy of poetry in the twenty-first century cannot avoid a catastrophic calculus: the rate of consumption quickly hits an arithmetic limit (any one person can only read so much), but the rate of production is increasing geometrically.

We are used to being told that there is not enough poetry, that ours is a culture that “renders (poetry) insignificant and invisible— that poetry is so marginal it doesn’t matter.” Rather than marginal, Dworkin asks, what if the problem is that we live with too much poetry? Even if we optimistically assume that “somewhere—with lonely bloodshot eyes—a handful of obsessive readers are in fact managing to keep up (…) they have precious little time to do the additional reading that would put those books in context.” Dworkin posed these questions back in 2008, long before the advent of ChatGPT, which, if it is ever trained to compose beyond the heroic couplet, will no doubt infinitely exacerbate the numbers.

Installation view of Re-departures—Works from Melbourne and France at Visual Diary, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

Michael Farrell, c.2022, Certified Colour, collage and watercolour on paper, 297 x 420. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

So why tune into Farrell, against the drone? Why is it that, without fail, his artworks make me smile? One wall of the gallery space at Visual Diary is covered with Farrell’s collages, here revealed to be A3 works (surprisingly large in comparison to how they appear on the Instagram grid). Many of the collages feature snatches of text: “The only failure is to not try” and “Be your own beau.” These affirmations, cobbled together from magazines, are like koans: they may be utterly profound or utterly vacuous—depending, in large part, on the mood of the viewer. Another collage, near the gallery’s entrance, has something of the clipped impersonal perseverance of late Samuel Beckett (“Somehow nohow on…”), but recovers quickly with a second line: “Go on. Behold the art.”

Historically, poetry has maintained something of a rivalry with the visual arts, as is expressed in a common genre of envious ekphrasis, in which poets treat their own medium as belated and suspect by comparison to images. “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty” is the efficiently direct message of a Grecian urn that Keats takes fifty lines to impart. In “Why I Am Not a Painter?” (1957), Frank O’Hara complains:

I am not a painter, I am a poet.

Why? I think I would rather be

a painter, but I am not.

O’Hara’s friend, the painter Mike Goldberg, makes a representation of a sardine, or paints the colour orange, and his subject can be immediately apprehended. He has made his imagination visible—made it a physical object—in the world. By contrast, O’Hara explains, a poet is set the much trickier task of describing a silver sardine or the idea of the colour orange—and, because of the messy medium of language, they can never be sure that what they have in mind has been communicated. “It is jealousy on the part of writers,” says French poet Yves Bonnefoy, that leads to a “desire to destroy what (they do) not have and that (they) love all too much.” The best paintings seem “nothing short of miraculous,” he adds, for they satisfy “the desire for the immediate”—for pure sensation, like a “flash of lightning,” uncorrupted by conscious decoding.

Installation view of Re-departures—Works from Melbourne and France at Visual Diary, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

Collage has the potential to be still more coterminous with its subject than both poetry and painting. Why make a representation of a newspaper—or, as Farrell demonstrates, the spinner from a Twister board—when the represented object can itself be picked up and affixed to the canvas? But Farrell does not share in O’Hara’s handwringing. Even in his collages, he remains indirect, embracing a poet’s love of misdirection which is, at turns, personal and cryptic. “We’ve come out” is pasted above a photograph of a woman and two children, together with a picture of unearthed animal bones. In a work titled “Neanderthal Freedom,” a black-and-white lothario with a pencil moustache has been assembled with a shirtless cowboy’s midriff, his belt and holster showing. He wears hand-drawn trousers and boasts an edible crutch: a photograph of a caprese bruschetta, cribbed perhaps from a 1970s cookbook or food magazine, looking at once dated and delicious, with mozzarella, tomato, and basil. This brief description risks oversimplifying the work into a straightforward one-liner—a macho-queer Frankenstein—when its visual impact is in fact disguised by extraneous lines and interpretively challenging elements (an image-shard of archaeological pottery is arranged horizontally down the page). What is significant in Farrell’s collage is not the alignment or juxtaposition of a discrete element or two, but the way they are assembled to produce multiple semiotic patterns overall.

Throughout Re-depature, there are numerous nods to Dada, and to the movement’s twenty-first century inheritors, such as Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan: instead of a banana, a clock, a light switch and carpet-sample have been duct taped to the wall. But where contemporary Dada can feel more like calculated artworld spectacle than a labour of love (Cattelan’s Comedian is not, according to Rex Butler, “any more a work of art, but just a banana on a wall for people to take pictures of themselves with”), Farrell maintains the homespun exuberance of the earlier movement. A Schwitters in Brunetti Classico cafe, Carlton, he draws in colour pencil on the backs of his coffee receipts.

Installation view of Re-departures—Works from Melbourne and France at Visual Diary, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

Installation view of Re-departures—Works from Melbourne and France at Visual Diary, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

Re-depature is a merzkunst which embraces not only collages, but prints, murals, readymades, and paint-stamped shoe treads on the floor. A window ledge is lined with unassuming ceramics—one titled Changes (after the Bowie album), another Philadelphia (referencing the Tom Hanks movie, not the place)—that are surrounded by orange peel decorated with daubs of black paint. An artist’s book titled Hate Paintings defaces an illustrated history of the British royal family. These all feel like active experiments, rather than dutiful references to art history. In Farrell’s poem Folktales of the Avant-Garde (2020), the tired story of European artistic revolution is supplanted by lively campfire gossip. “Who should we talk about?,” the poem asks: “The girl with the button eye? / When she tied herself to a sunset it looked like she could fly / (…) The coffin with legs that walked? / For some reason they were always talked about as if (they were) a man. (…) The childless crying rabbit? / (…) They say the rabbit’s burrow is the oldest avant-garde cave / In the country and all agree that the wool works are marvels.”

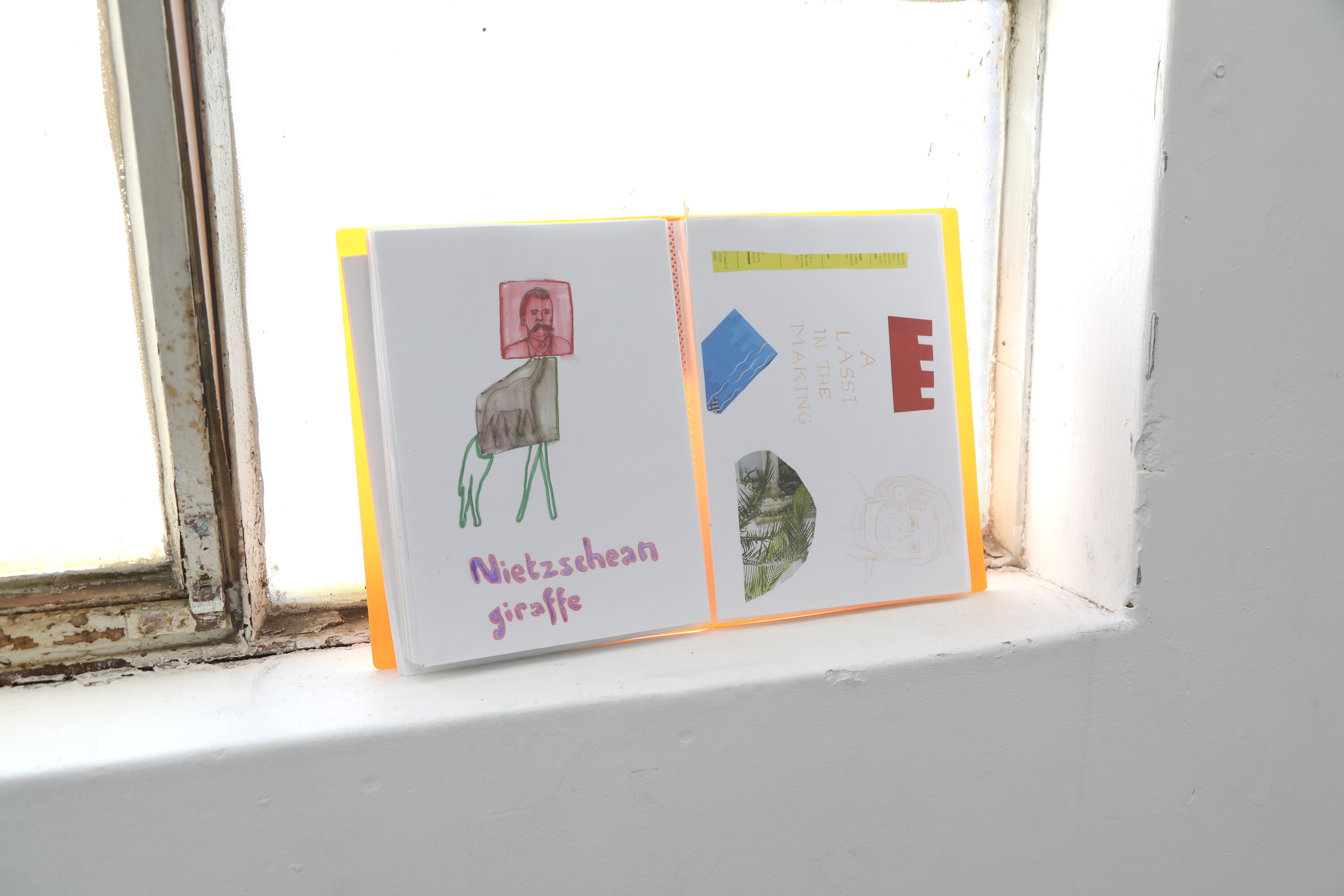

Michael Farrell, c.2023, Nietzchean Girraffe and A Lassi in the Making, pencil, watercolour and collage on paper, 210 x 297. Image courtesy of the artist and Visual Diary.

As Farrell is aware, even the most hardline avant-gardes frequently have soft and playful precursors: Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear wrote portmanteau and nonsense verse for children long before Marinetti called for a new Futurist orthography, “free to dismantle and remake words, (…) vowels and consonants.” Innovation is as possible at the periphery as in Paris, London, and New York, even if cultural centres still struggle to recognise regional avant-gardes. This, at least, was the argument of Farrell’s 2015 scholarly monograph Writing Australian Unsettlement: Mode of Poetic Innovation 1796–1945, which brings together an idiosyncratic counter-canon of colonial Australian poetry to provide an “example of how (Farrell) read(s), or a proposal of how—or what—others might.”

Again and again, the book demonstrates the pre-eminence of the regional, each time with astounding examples: Ezra Pound’s “invention” of the ideogrammic method was a belated successor to the Chinese goldminer Jong Ah Sing’s multilingual experiments in the 1860s; Dorothea Mackellar, author of jingoistic lyrics (“I love a sunburnt country, / A land of sweeping plains”), also developed complicated poetic cyphers to encode her extramarital infidelities; whereas concrete and minimal poems, authored by drovers travelling the Murranji Stock Route, date back to the 1890s or earlier. “Australia was never meant to be fun,” Farrell memorably observes in a chapter on the theme of boredom in colonial poetry. European invasion sought to establish a “convict settlement where England’s victims were sent to ‘pine their young lives away in starvation and misery’.” Yet in Writing Australian Unsettlement’s liberated archive, and in Farrell’s wider creative oeuvre, Australia is recast as a place not only of interest but of pleasure and joy. A collage in Re-depature reformulates Farrell’s earlier aphorism: “Australia (…) half the fun is looking.” If this exhibition is connected to Farrell’s longstanding research and poetic projects, it is through his insistence that there is no wrong place, time, or method to make art.

And this, perhaps, indicates why artists like Farrell are indispensable. Even within a modern deluge of words and images that can feel stifling, Farrell declares contemporary art as necessary. We all get tired of reading and looking. Who among us cannot sympathise with disgraced Tory strategist Dominic Cummings, who, after only two weeks of Zoom calls during the UK COVID-19 lockdown, fled London for Barnard Castle, where eyewitnesses described him wandering the countryside, calling the bluebells “lovely”? The human animal longs for the woods, some peace away from the Google meet, Instagram grid and MailChimp invitations to exhibition openings.

Farrell is not this type of artist—not sentimental about some sort of conservative return to a clean, pure state of nature. With his conveyor belt muse, Farrell keeps pace with the march of culture. But if, by some miracle, we could turn the faucet off, or negotiate a peace deal in the arms race for new content, even then, Farrell suggests, we would not be able to enjoy the existing spoils of culture. Art, without artistic production, becomes history; it is rendered mute, unresponsive, incomprehensible. It is only through acts of making and remaking that we are able to recognise art in the first place. To tune out, as Farrell elsewhere puts it, is to avoid “treading on a snake” only to step “on a landmine.”

Brendan Casey is a writer living in Naarm