Philadelphia Wireman

Giles Fielke

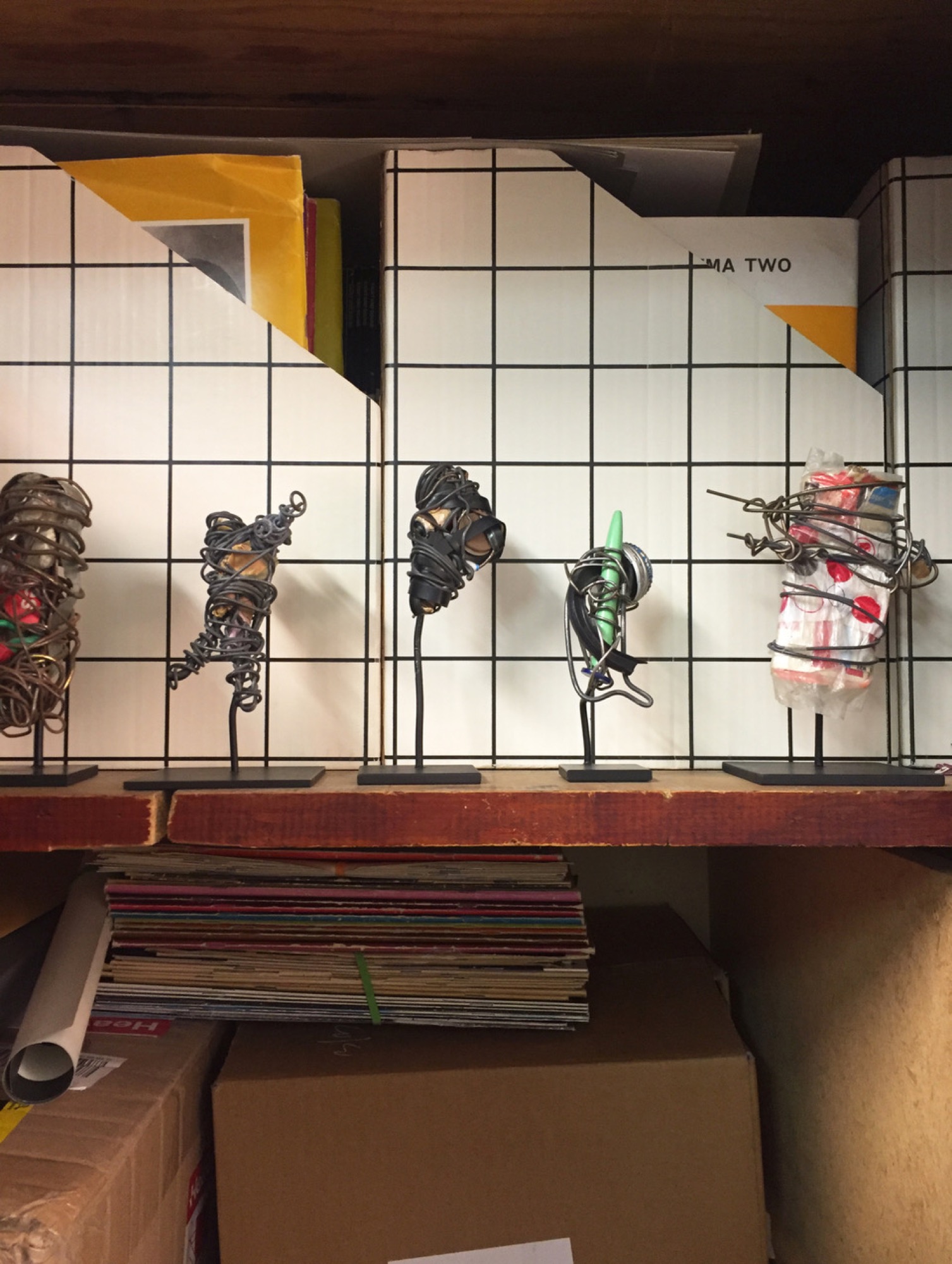

There is an overwhelming temptation to fill in the constitutive blanks where an artist’s life should be, but here there is no artist, only the artworks remain. The evidence of the so-called Philadelphia Wireman’s life is patchy, effectively non-existent. Enough facts remain, however, to establish a scene. Twelve of the some 1200 small, meticulously bound-in-wire sculptures and drawings found dumped in a lane off that city’s South Street in 1982 are currently on rotating display at World Food Books in the Nicholas Building.

The program for their exhibition, devised by Melbourne artist and bookseller Joshua Petherick, groups them into smaller clusters over the course of the five-week ‘Occasion’, one of a series held in the small shop space. A simple, metre-long ledge has been fabricated for their display at eye-level on the book-store’s eastern wall. Beginning August 3, a trio of the works were displayed initially: PW 640, PW 944, PW 374. Now two: PW 26 and PW 32. Next week three more: PW 902, PW 776, PW 1084. Another three the following week: PW 900, PW 885, PW 905. And finally, just one: PW 466. South Street in Philadelphia begins at the University of Pennsylvania and ends at the Delaware River. It is this strip that frames the intricately laden objects, packed with debris. Sometimes they are taped over and flecked with marker. They are tied to a particular time and place. The drawings—not included here—were found alongside the boxed and discarded sculptures, and look like Henri Michaux inks. All of the sculptural works share the same central characteristic: their support is tightly twisted medium-gauge wire.

Recently, Hamishi Farah exhibited a simple portrait of fellow painter Dana Schutz’s son. Included at the LISTE Art Fair in Basel, the image was a deft manouvre in the ‘contemporary art as culture-war’ campaign, and responded to Schutz’ ‘motherly’ portrait of Emmett Till (who was murdered in 1955) at last year’s Whitney Biennial. By continuing the logic of identity politics as the grounds for art-making today—foregrounding who may make what painterly gesture—these works imply an argument about the relative importance of the artist’s position within the constellation of the art-world, as industry. The marketability of the Philadelphia Wireman, when, as the exhibition notes state, ‘the maker’s name, age, ethnicity, and even gender remain uncertain,’ makes the fetish character of the found objects bound in wire appear doubled, the fetish of a fetish. McDonalds stirrers poke out, pennies are buried within, small hexagonal nuts are threaded onto the wire, pen caps are bound into their interiors with centrifugal force. When tape masks them, the works often look doll-like and bodily; some have nails penetrating all the way through. Others are wrapped with plastic. Colour spills out in unexpected ways: the solid teal of pen cap Bakelite against the gun-metal grey wire.

There is a troubling line that is the crux of Michelle McNamara’s posthumously published book, I’ll Be Gone In The Dark, about her all-consuming obsession with finding the Golden State Killer. McNamara implies that DNA forensics in California normalised genetic profiling in the 1980s, re-creating every citizen as a barcode shared and made accessible by law enforcement agencies. This was allowed to happen, encouraged in fact, because it mitigated against the fear of violent and sadistic attacks by madmen in the featureless and anonymous suburbs of rapidly expanding counties. With the emergence of tract housing and transient or upwardly mobile tenants, anonymous citizens needed to become identifiable. This was done with a biometric code. The serial-killer, Joseph DeAngelo—a former police-officer still living in the Citrus Heights neighbourhood where many of his attacks occurred—was finally arrested this year, more than thirty years after his last alleged murder. DeAngelo had recently retired, he was divorced, he is the father of three children. The Golden State Killer’s DNA was matched through the publically accessible GEDmatch.com. The period in question, 1970s North America, matches the Wireman works too well. Later, David Lynch and Mark Frost invented Laura Palmer, referring to this horrifying aspect of post-war USA, as did the Scream movies.

As I stare intently at the Wireman sculptures in the bookstore, I wondered about testing the Wireman sculptures for traces of DNA. What would it reveal? An African-American male making icons for a post-Fordist landscape? A woman, who died alone in an area of Philadelphia that at the time was rapidly gentrifying, her work posthumously dumped by Yuppies in a back-alley for the trash-collector to take away forever? An anonymous life spent in and out of institutions, only to be salvaged by Robert Leitch, who gave them to friends as gifts before submitting them to Janet Fleisher, first showing them in 1985? A serial-killer of objects, tortured and strained to their makers’ private ends, the Wireman is ultimately the incomplete sum of all of these parts.

Why is identity important here? The obvious point to make is that we all too easily fill these works with our own meanings and desires. People see in them what they want to see. Furthermore ‘self-taught’ art is often at risk of becoming a kind of holy grail for the art market, and for that reason extra-special care—curation—is needed for their display. The works can be shaped and moulded by a gallery with a vested interest in their exhibition and sale. Some believed the Wireman works to be an elaborate hoax by a group of artists fully aware of Art Brut and public willingness to fetishise the other. Perhaps they are Vodou objects, possessing the spirit of their age, and because it shows how art also operates outside of the art/artist dualism, these wire-bound sculptures function to constantly bring us back to the question: what inspired someone to obsess over, and to struggle to make such complex and tortured assemblages of trash?

Annette Michelson writes on the rupture—perhaps the rupture between the artist and the artwork, the tear in totality, in a 1991 essay focussing on the legacy of Andy Warhol. The Factory becomes the site of a ‘deviant logic’, and in this way it is not only an exception but also ‘preeminantly of our time,’ because these productions remain abject to the function of industry. Michelson speaks of a time posed as a rootless modernity, where experimentations with baseless religious reverie abound. In Philadelphia, the United Church of the Ministers of God amassed a small fortune before its leader, Gary Heidnik, was charged with multiple murders and kidnappings in 1987. Critical comparisons of the Wireman to morphologically similar artworks by Mark Tobey, for example, may become problematised by the larger social circumstances in which the works relate to their immediate environment. Contemporary artists like Lonnie Holley, or Yuji Agematsu, in the quality of their long-term practices of collecting trash, provide a more authentic narrative, perhaps, to similar approaches within more institutionally recognisable projects by artists like Gabriel Orozco. The problem is that there will always remain a yawning gap in our wish to know the Wireman. This is a functional gap, especially for the art-market.

After Leitch donated the collection in 1985, research into the objects bound up in the works has allowed them to be dated back to as early as 1970. The Fleisher-Ollman Gallery, which has previously shown the work of other ‘self-taught’ artists, such as Henry Darger and Sister Gertrude Morgan is therefore the first point of contact for the Wireman myth in the context of the market. Reconstituted as art, ‘found’ objects like these—regardless of their maker—draw upon a modernist tradition that has its basis in the ‘found’ objects of Primitivism and Orientalism. Namely, the other is dispossessed of their cultural symbols, which are then appropriated by their colonisers; later they are re-appropriated surreptitiously, in houses, and marginal spaces, hidden from view—they look insignificant, they look like like trash. Les maîtres fous, Jean Rouch’s controversial 1955 film, showed how those subjugated could ‘re-appropriate’ their own images back through the lens of their masters. This double-negation transforms the image in a historical way. All of a sudden, pieces of trash become highly charged deities. This is the logic of historical materialism, all that is solid melts into air—and all that is discarded will be re-generated, venerated as closest to god. These inverted high/low hierarchies are playing out again right now—base culture is on top. Sky News happily promotes neo-Nazism, while claiming to defend free speech.

‘Heavy with associations’ is how the announcement on World Food Books advertises the Philadelphia Wireman show. Petherick opened the small bookstore with artist Matt Hinkley, who has since re-located overseas, in 2010, dedicating it to new and obscure second-hand texts on modern and contemporary art. Its location on the third floor of the Nicholas Building puts it at the crux of Melbourne’s art-scene. Furthermore, that it ‘semi-regularly co-ordinates “Occasions”,’ as it is put on the website, proposes an alternative space for encounters with art and it’s difficult and complicated histories. These have included, most recently, Susan Te Kahuranghi King, Mladen Stilinović, B. Wurtz, and Buchill/McCamley, amongst others. With this the most recent Occasion, the Philadelphia Wireman proposes a far more ambitious gambit: Where will art go if our artists are better when they are anonymous?

Giles Fielke is a writer and musician working at the University of Melbourne. He is the Business Manager of the AAANZ.

Title image: Philadelphia Wireman, Untitled (Plastic bag with blue writing), c. 1970–1975, Wire, found objects, Mixed media, 7 1/4 x 2 3/4 x 2 1/2 inches, 18.4 x 7 x 6.4 cm, PW 26. Image courtesy World Food Books.)